The AHS Blog

Graveyards, clocks and bombs

This post was written by James Nye

Things end up in graveyards at the end of their lives, but monuments to the passing of much else can be found in other locations.

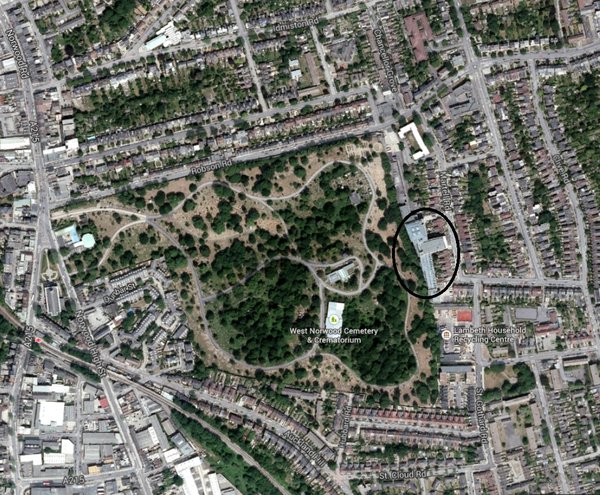

I live in West Norwood, home to one of the ‘magnificent seven’ London cemeteries.

On its eastern boundary lies the Park Hall Business Centre. This thriving modern enterprise occupies the former Hollingsworth Works of the Telephone Manufacturing Company (TMC).

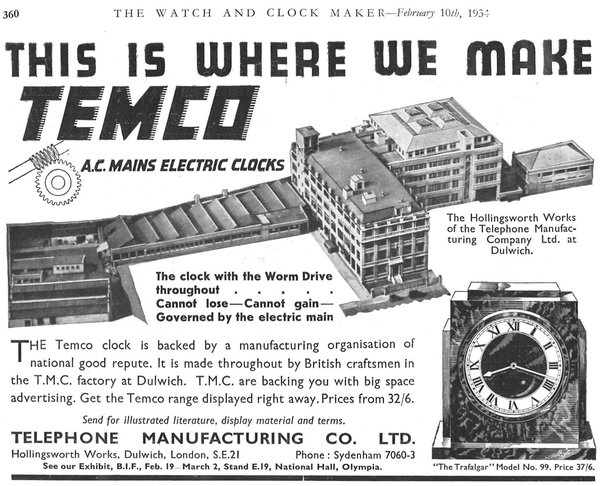

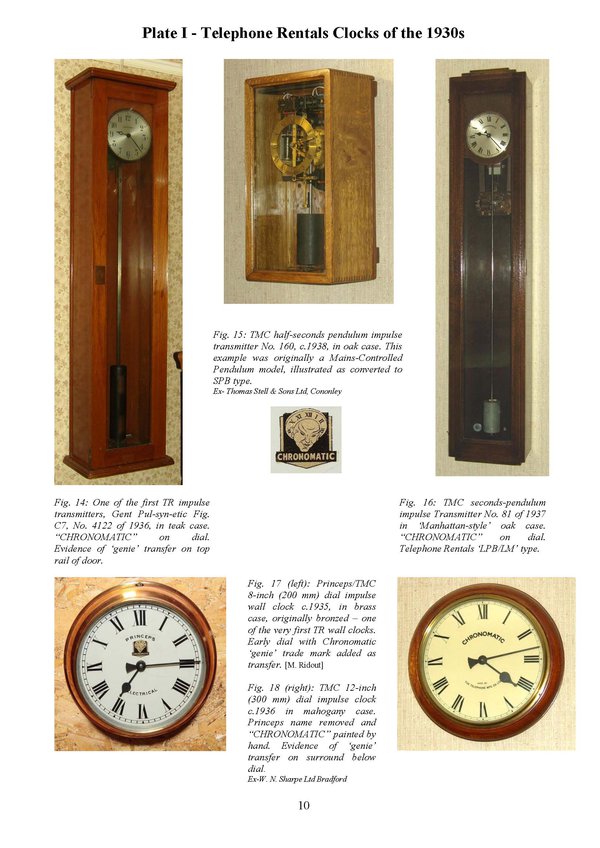

This firm did just what its name suggests, but was also a prolific maker of industrial timekeeping systems, rented out under the name Telephone Rentals. TMC’s ‘TEMCO’ synchronous clocks are featured in the latest NAWCC bulletin.

TMC occupied the Dulwich site from the early 1920s, employing a large local workforce—1,600 by 1937. Workers from the other side of Norwood Road used to talk of ‘walking the wall’ to work, following the long cemetery flank wall, down Robson Road.

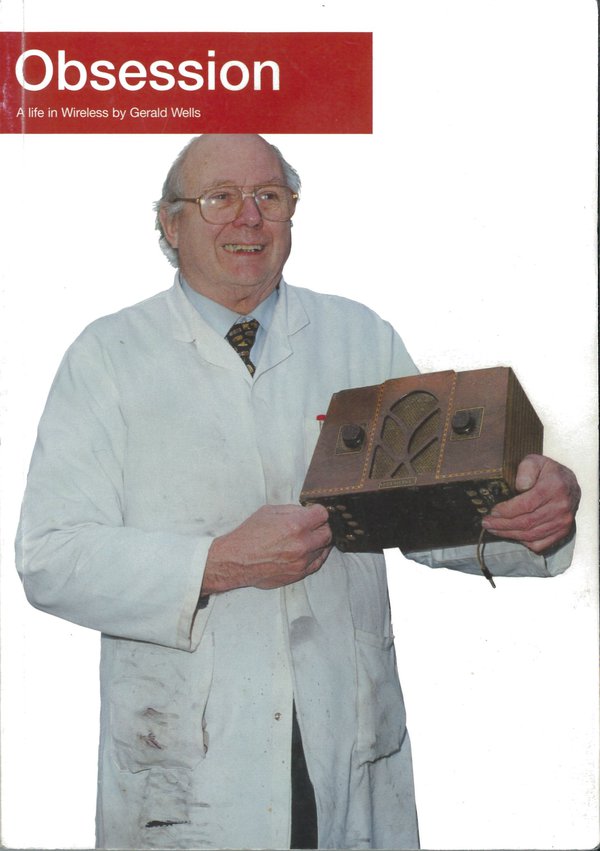

Involved in contemporary ‘hi-tech’, the factory was a natural wartime target—Gerald Wells’ extraordinary autobiography describes twenty-seven bombs falling on the cemetery, targeting TMC, but then the Luftwaffe became:

‘fed up with wasting bombs on Norwood Cemetery so they decided to get the TMC factory by lowering a large naval magnetic mine on a parachute over the building. My sister Margaret watched it come down from an upstairs window […] it knocked seven colours of s*** out of our little Congregational Church’ ( click for a bombsight map —work in progress).

So Hollingsworth Works survived, and TMC/TR had a more successful post-war life than many clock-related concerns.

You can learn much more about the company’s life and products from a superb paper by Derek Bird—these technical papers are a feature of EHG membership. Why not e-mail me to get on board? And put 7 September 2014 in your diaries—part of Lambeth History Month—when The Clockworks will offer a special locally-themed event, featuring TMC.

Musical clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My previous post in this blog was on clocks in opera. How about opera in clocks?

The Handel House Museum is the London home where the composer George Frideric Handel lived from 1723 until his death in 1759. In the 1730s, Handel provided music for a series of musical clocks created by the watch and clockmaker Charles Clay.

These more than man-sized, elaborate pieces of furniture were fitted with chimes and/or pump organs that at the hour and every quarter played musical excerpts from popular operas and sonatas.

Until 23 February the Handel House Museum presents an overview of Clay’s clocks in an exhibition ‘The Triumph of Music over Time’. The centrepiece is a clock on loan from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; other clocks are presented as photos on text panels.

These panels are all on-line here where you can also listen to some of the music that Handel arranged for Clay’s musical clocks, including two pieces from his opera Arianna in Creta. So there you have it: opera in clocks.

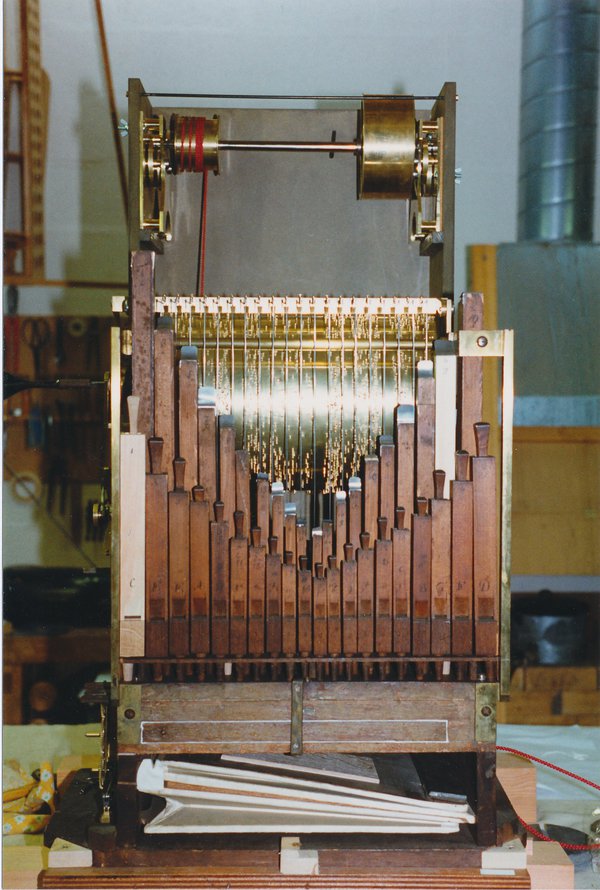

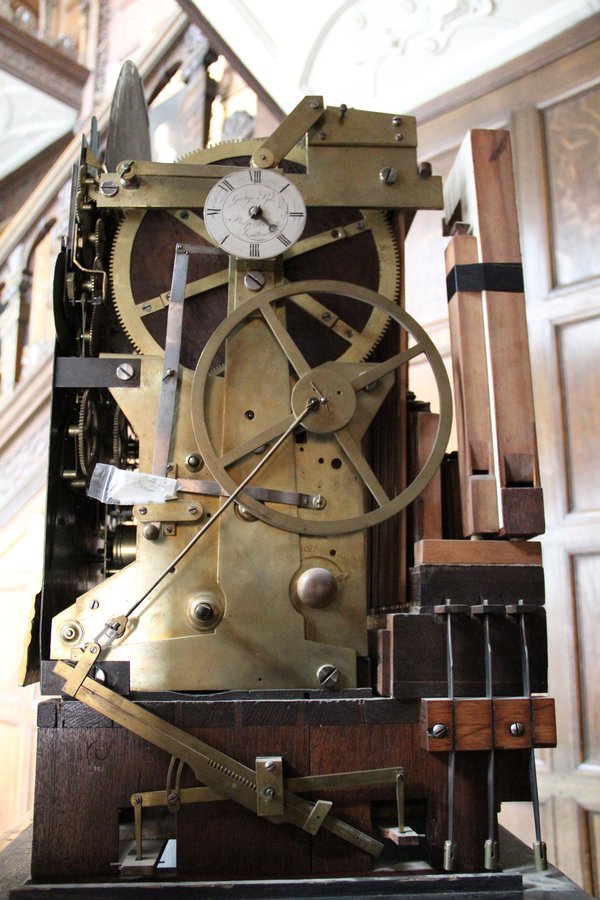

Another 18th century maker of beautifully crafted musical clocks was George Pyke. A fine example, dated 1765, is on display at Temple Newsam House in Leeds.

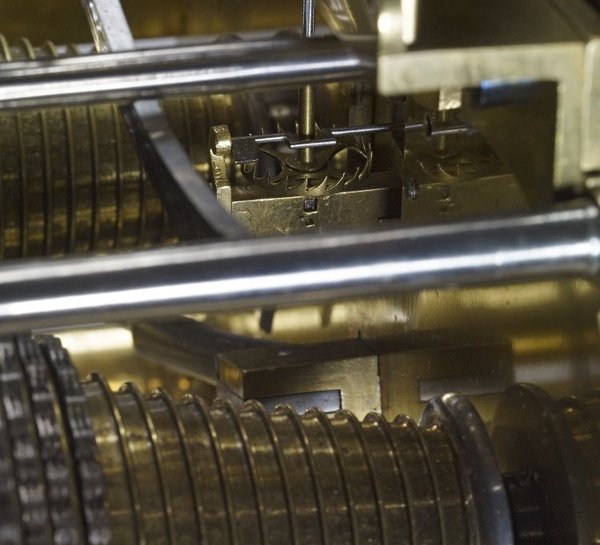

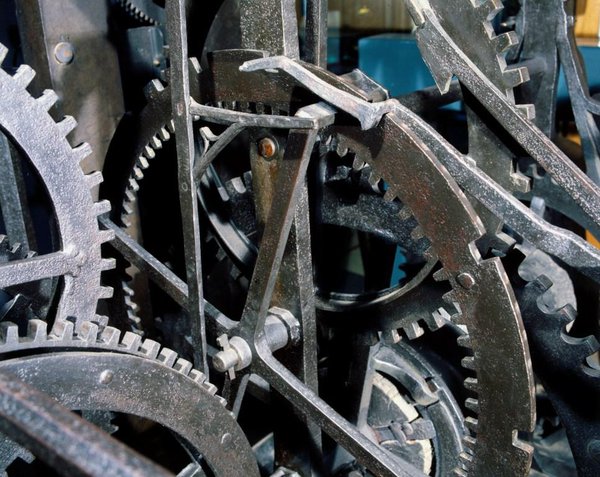

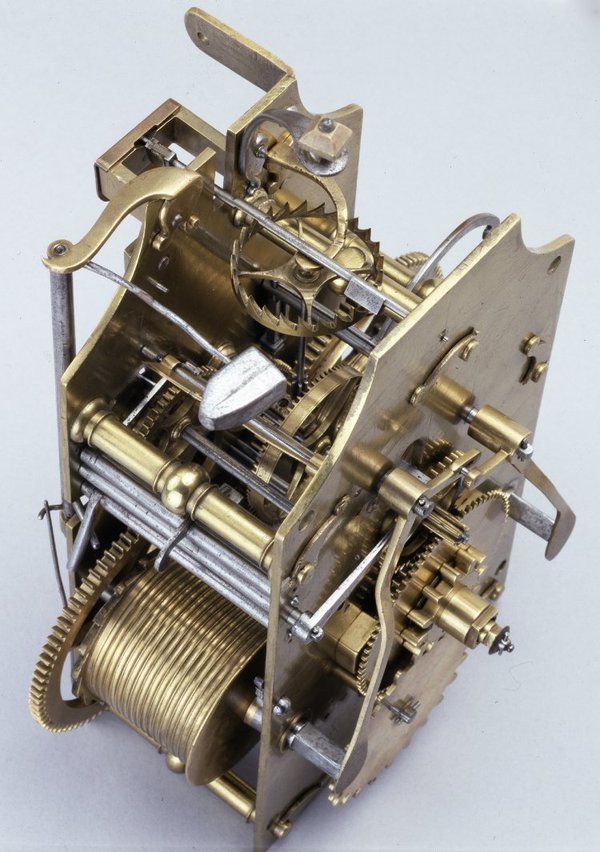

Standing over 6 foot tall on its pedestal, it strikes the hours and has a pipe organ that plays eight tunes. The innards of the Pyke clock are shown below; more photos and details of the clock are here on the website of Brittany Cox, who has made a condition study of the clock and hopes one day to be able to restore it to its former glory.

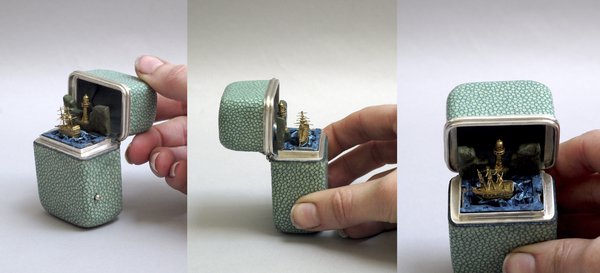

Although a bit off topic – it is not a clock – you may like to know of a musical automaton that Brittany Cox restored to working order during her studies at the Clocks and Related Dynamic Objects Department at West Dean College. A miniature ship, a mere 15mm wide, rocks to and fro, as in a storm, while ‘God Save the King’ plays on a plucked comb; see and hear it here.

For this project Brittany was awarded the annual AHS prize for 2012. For a full description see this article which she wrote for our journal Antiquarian Horology .

With thanks to Ella Roberts, Communications Officer at the Handel House Museum, for her help.

A million free images

This post was written by David Rooney

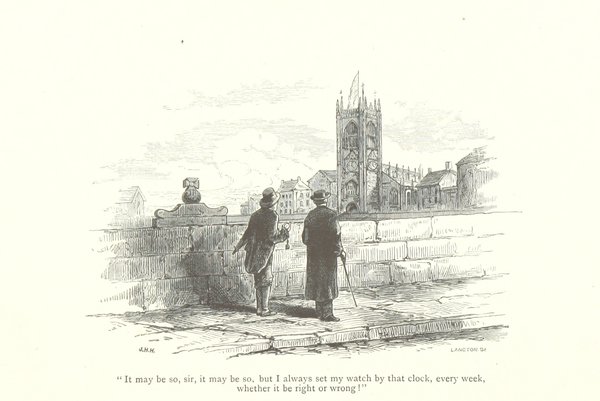

Just before Christmas, the British Library released over a million historical images from its printed collections onto the image-sharing website Flickr. The images are out of copyright and the library has made them available with a Creative Commons licence which, in short, encourages anybody to use, remix and repurpose them, so long as they respect a few ground rules.

This is a remarkable resource of imagery and will be a boon for anybody carrying out historical research – such as AHS members.

There are countless images of interest in this release, each one of which might augment an existing research project or prompt a new one. The beauty of archives such as this is the opportunity for lateral thinking. You might be researching a particular village, or writer, or building, or period. And you might find an image here that opens up new avenues of research.

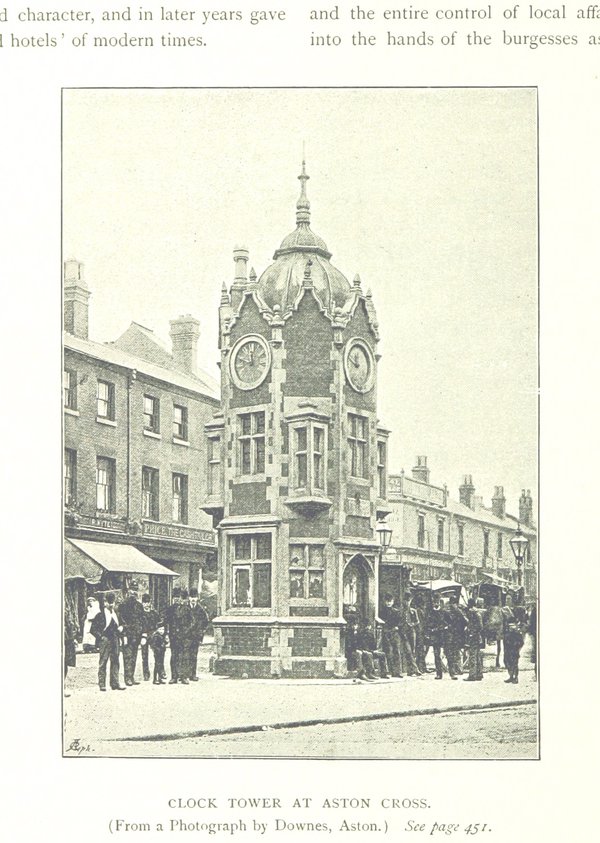

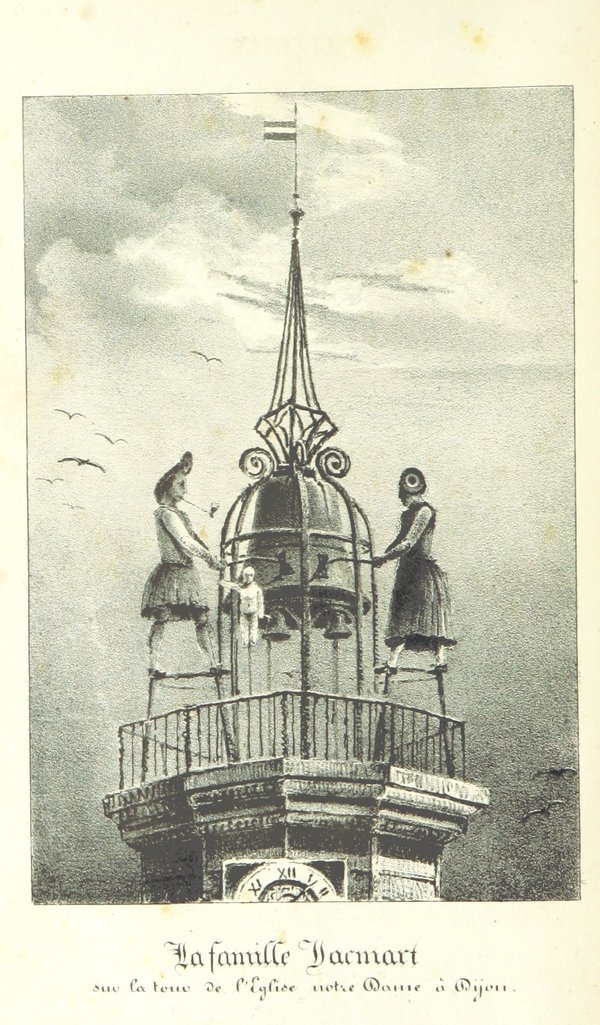

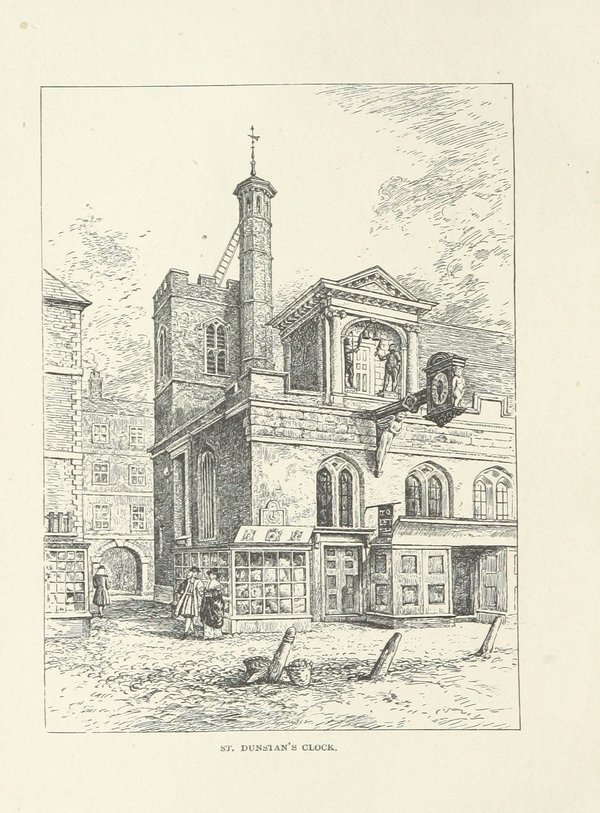

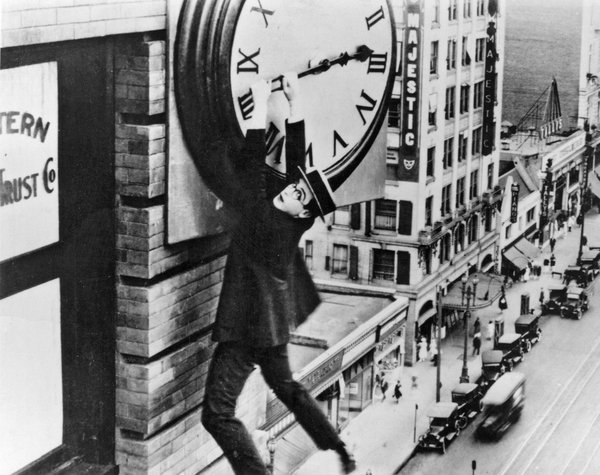

The first four images I found are the result of searching for ‘clock’ or ‘clocktower’ – as you’d expect, lots of public clocks.

But let’s say I’m interested in chronometers. Unfortunately there are no search returns for that word. But then I tried searching for ‘observatory’, and found this image.

It’s from a book on the North Polar Expedition, and it’s a photograph of marine chronometers on show in a US Navy centennial exhibit in 1876.

That led me to this catalogue of the objects exhibited. And on pages 79–81 there’s a remarkable and detailed description of the use of chronometers at the US Naval Observatory in the 1870s. Serendipitous discovery is a wonderful thing.

You’ll probably want to put aside an hour or two browsing these images – and a lot more time following the interesting leads they throw up! Happy hunting, and happy new year.

The sands of time

This post was written by David Thompson

Everyone is familiar with the egg timer, but just how far back in history do these glass timers filled with free-flowing material go?

The earliest known illustration of such a device exists in an Italian fresco dating from between 1337 and 1339 in the Palazzo Publico in Siena. The fresco is called ‘The Allegory of Good Government’ and in it, one of the figures can be seen holding a sand-glass.

Before modern glass making techniques developed, sand-glasses were made using two separate bulbs bound together around a disc with a hole for the ‘sand’ to pass through. Over the centuries all manner of different materials were tried in attempts to achieve a uniform free-flowing performance.

The duration of the timer depended firstly on the amount of ‘sand’ in the glass, and secondly on the size of the opening between the two containers. The two glasses were sealed together with wax and the joint covered and tightly bound. The biggest enemy for these glasses was humidiy – damp ’sand’ was bad for business.

A particularly fine example exists in the British Museum collections, although is has a rather dubious reputation.

It is a composite glass with four separate glasses in a beautiful ebony frame and each glass is designed to run for a different period, one quarter, one half, one three quarters and last a full hour. It even boasts a leather carrying case.

At one time it was said to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots and indeed, at the top and bottom of the frame are reverse-painted glass discs bearing the royal shield of the Tudors and the shield of France with fleur-de-lys. The idea was that this glass was owned by Mary Queen of Scots and Francis II, king of France.

Unfortunately, the Tudor arms are from the wrong period and the lion rampant in the first quarter of the shield is the wrong way round. The leather case is also roughly embellished with the monogram MF for Mary and Francis.

In spite of its later enhancement, this is nevertheless a very fine example of a late 17th century glass.

On the one hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

The last of the five elements is the indicator, the part of the clock or watch that conveys the time.

Early clocks and watches typically only had a single, hour, hand. This was more than adequate for indicating the time as these foliot-controlled timekeepers would typically lose or gain at least quarter of an hour in a day. Minute and seconds hands only became truly useful with the vast improvement in timekeeping that came with introduction of the pendulum in 1657 and the balance spring 1675.

However, the familiarity, simplicity and economy of the single hand meant they never became obsolete. Throughout the 18th century, pendulum-controlled longcase clocks with single hands were very popular in the provinces of England.

There were also some more interesting implementations of the single hand. This balance spring watch has a six-hour dial, instead of the usual twelve-hour dial. With only six hours dividing the circle it offers twice the resolution of a standard twelve-hour dial, thus going some way to making up for the lack of a minute hand.

Next, a single hand with a difference – it is telescopic. The hand extends and retracts to follow the contour of the oval dial, allowing the time to be read clearly. A fixed hand would fall short at the “XII” or “VI” positions, making it harder to read with accuracy.

Another form of single hand can be found on this Japanese pillar clock.

The pendulum controlled movement is at the top of the clock. Below it, the single, hour, hand is directly attached to the driving weight through a slot in the case. As the weight descends over the course of a day, it indicates the time against the linear scale of numeral plaques on the case. The plaques can slide, which allows their positions to be adjusted for the Japanese system of unequal hours.

Single handed watches continue to made by several manufacturers, such as this example owned by myself.

In practice, the time can only easily be read to the nearest five minutes (which is well within the capabilities of its modern movement). However, I find that this is good enough (at the the weekends at least!) and it is a most leisurely way to follow the time.

300 years

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

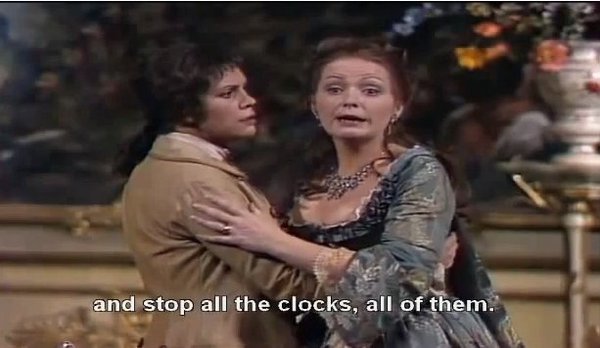

This year saw the tercentenary of the death Thomas Tompion (b.1639), the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’ and his life is celebrated in two special exhibitions: the first at the British Museum, entitled ‘Perfect Timing’, which focuses on the magnificent Mostyn Tompion and the second, ‘Majestic Time’, at the National Watch and Clock Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Tompion enthusiasts should be further delighted by the announcement of the forthcoming publication of ‘Thomas Tompion, 300 years’. The book promises a wealth of new detail, fresh illustrations and includes Jeremy Evans’s previously unpublished chronology of Tompion’s life.

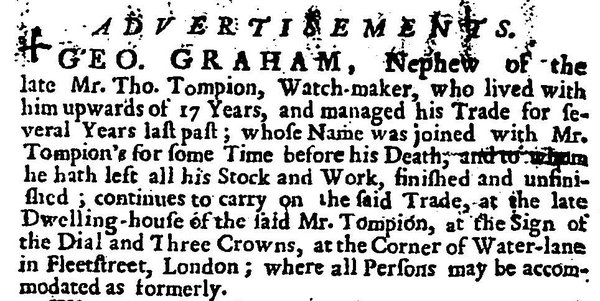

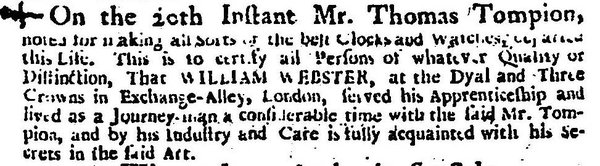

This tercentenary marks not only an end, but a new beginning as Tompion’s nephew by marriage and then business partner, George Graham (c.1673-1751), inherited and continued the business at the corner of Water Lane. As far as I am aware, the earliest announcement of Graham’s succession was first advertised in The Englishman one week after the death .

William Webster, however, did not show the same reserve. He had an advert published the day after Tompion’s death in two papers: The Mercator or Commerce Retrieved and The Englishman. His announcement of the death was a thinly veiled attempt to attract business and was repeated in various papers that week.

Unlike Webster, Graham was not apprenticed to Tompion (several publications incorrectly cite Graham as being so). He joined the household sometime around 1676 after gaining his freedom from apprenticeship to Henry Aske.

Evidence suggests that Graham did not serve his entire apprenticeship under Aske and it is currently a mystery as to where he was during the last years of his apprenticeship.

Looking forward to next year there is another important tercentenary, that of the Queen Anne Longitude Act. George Graham played an important role as an encourager and advisor to both Henry Sully and John Harrison in their efforts to produce sea-going clocks and will feature in a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum next year.

Happiest days of your life?

This post was written by James Nye

Recently we hosted the BHI North London branch at The Clockworks. It was a great visit, filled with observations and anecdotes about life among clocks.

Always popular, we looked at the Gent’s 'waiting train’, or ‘motor pendulum’. A neat design, synchronised to an accurate source, it has the power to overcome harsh winds or snow impeding the hands, compensating with more frequent impulses when needed.

Chatting over a coffee, stories emerged of people’s introduction to clocks and watches – particularly electric ones.

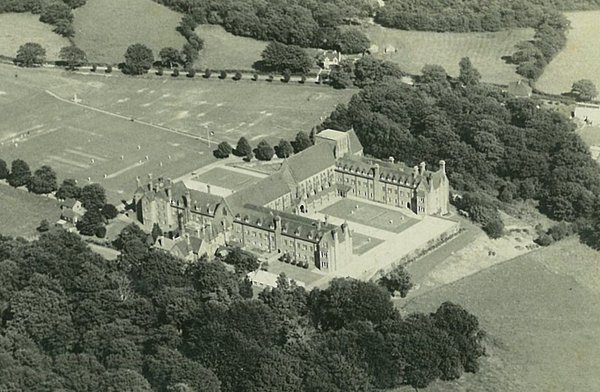

I described how, at the age of 13, I was put in charge of my school’s Gents-based clock system (for the nerds, C7, C69, C150 etc), including a waiting train in a tower above. One guest mentioned that coincidentally it was the same for him – being asked to tend to just such a school system.

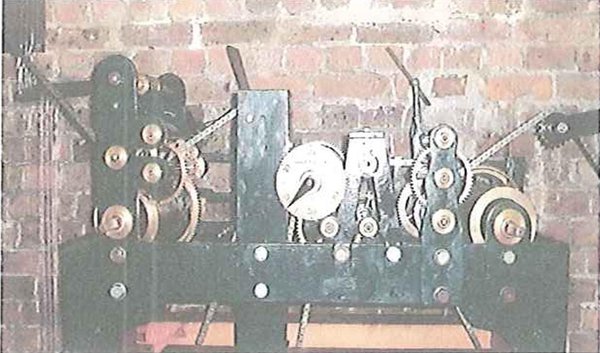

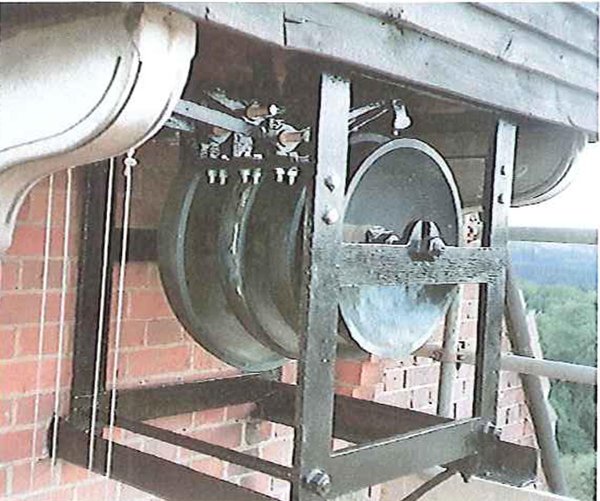

This prompted me to describe a feature of the system I maintained. A flatbed turret clock (David Glasgow, 1911) provided a chime and strike on bells, tripped by a solenoid, in turn controlled from the waiting train, using four aluminium sails (like a windmill) mounted on the bevel nest, operating each quarter on a microswitch – an ingenious addition.

‘Which school was this?’ asked a misty-eyed guest. ‘Ardingly College’, I replied. ‘That was me,’ he said softly, ‘probably in 1950.’

A quarter century apart, we had both been responsible for the same system. George D’Oyly Snow, headmaster, was fed up with chimes sounding at the wrong time, and with limited funds, but knowing the inventive skills of his boys, he commissioned my guest to find a solution – a solution still functioning into the late 1970s.

A theme I mentioned in a recent lecture is the serious risk to which electric clock systems are subject when their caretakers or installers move on.

The Ardingly Gent system, probably in service since the 1930s, was replaced after approximately 60 years by a radio-controlled master clock, and Thwaites & Reed recently reworked the flatbed movement, installing motor-wind, and even synchronization.

George Snow can rest easy in his grave – the chimes still sound on time. But to my mind they must sound a plaintive note as well – curiously, I feel desperately cheated of part of my heritage, and I know someone else who probably feels the same way.

Clocks in opera

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

If you like music as much as horology (I do!), this is for you. For the links to YouTube you need a loudspeaker or headphones.

In Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi, the eponymous court jester hires an assassin to murder his employer, a plan that goes horribly wrong. He meets up with the assassin at midnight (‘mezzanotte’), punctuated by twelve strikes of the turret clock. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 46mins 20sec).

![Rigoletto: ‘The clocks strikes midnight’ – scored twelve times for the camp[ane], the tubular bells in the orchestra](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/bells-in-Rigoletto-Final-Act-1.width-600.jpg)

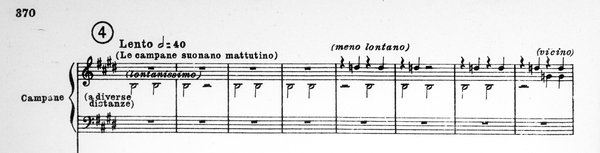

In Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca, Rome wakes up with the church bells sounding matins (early morning service). The instrument used in the orchestra is the tubular bells or chimes, metal tubes of different lengths hung from a metal frame, struck with a mallet.

The chiming is heard for more than two minutes, some bells sounding near, others in the distance. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 35mins36 sec).

Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov has a famous scene in which the Russian tsar has visions of the child prince he is suspected of having murdered. This is popularly known as the ‘clock scene’ and as there is no clock on stage nor in the text, this must relate to what goes on in the music.

Indeed, an obstinate, repetitive see-sawing theme is heard in the orchestra, but does it signify chiming or ticking? I am not sure. Watch it here (drag the timer to 0.58 for the ‘clock’ to start).

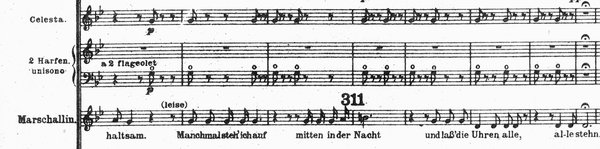

The most striking (pun intended) appearance of clocks in opera that I know is in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. An aristocratic lady has an extra-marital affair with a much younger man (sung by a mezzo soprano, one of the classic ‘trouser roles’ in opera).

Musing on how one day she will lose her young lover, as with the passing of time her charms will fade, she sings about the nature of time:

'Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding. Wenn man so hinlebt, ist sie rein gar nichts. Aber dann auf einmal, da spürt man nichts als sie. Sie ist um uns herum, sie ist auch in uns drinnen. In den Gesichtern rieselt sie, im Spiegel da rieselt sie, in meinen Schläfen fliesst sie. Und zwischen mir und dir da fliesst sie wieder, lautlos, wie eine Sanduhr. Oh, Quinquin! Manchmal hör’ ich sie fliessen – unaufhaltsam. Manchmal steh’ ich auf mitten in der Nacht und lass die Uhren alle, alle stehn'

or;

'Time is a strange thing When one is living one’s life away it is absolutely nothing. Then suddenly one is aware of nothing else. It is all around us, and in us too. It trickles across our faces, it trickles in the mirror there, it flows around my temples. And between you and me, it flows again, silently, like an hourglass. O, my darling, at times I hear it flowing – inexorably. At times I get up in the middle of the night and stop all the clocks, all of them.'

The music comes to a stand-still and all you hear is the chiming of a small domestic clock, played in the harps and the celesta – it’s magical. Watch it here sung in original German, with subtitles; drag the timer to 0.19.

Fine timing

This post was written by Paul Buck

A new exhibition has opened in Room 3 at the British Museum displaying the year going table clock by Thomas Tompion. This magnificent clock celebrates the coronation of William III and Mary II in 1689, and was kept in the royal bedchamber. It was made by a talented and industrious man who was in the right place at the right time.

Tompion’s modest beginnings as the son of a Bedfordshire blacksmith are recorded, but after that nothing is known of his whereabouts until he appears in London at the age of 32.

Wherever he had come from, he was extremely well trained in the making of clocks and watches.

London 350 years ago was the ideal place for Tompion’s genius to shine. In the previous century, religious persecution in the Netherlands and France had led to an exodus of Protestants, including many goldsmiths, silversmiths, engravers and watchmakers who established their trades in London.

Despite the Great Fire and the plague that preceded it, 1670s Restoration London was prosperous, with a plentiful supply of wealthy clients to support the burgeoning clock and watch trade. The new accuracy in clocks resulting from the application of the pendulum in 1657 followed by the balance spring in watches in 1675 was of great interest.

When William died the clock passed to Henry Sydney, Earl of Romney, Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Groom of the Stole. On his death in 1704, it passed to the Earl of Leicester and then to Lord Mostyn and remained in that family until 1982.

It is now known as ‘the Mostyn Tompion’ after its former owners.

The clock continues to keep good time, and is notably ‘year-going’ – it runs for over a year on a single wind. It also strikes the hours, an annual total of 56,940 blows on the bell.

This free exhibition is timed to coincide with the 300th anniversary of Tompion’s death in November 1713 and runs until 2nd February 2014.

If only I knew what the right time is

This post was written by David Thompson

When you want to know the correct time today, you either look at your mobile phone or you look at your radio controlled clock watch or listen to the six pips on the radio. However, don’t do the last one on digital radio as it is quite a bit out of sync with the real time – about two seconds.

Before the introduction of telegraph time signals and the distribution of time, everyone had to rely on a local observation of true solar time – that is, the time shown on a sundial.

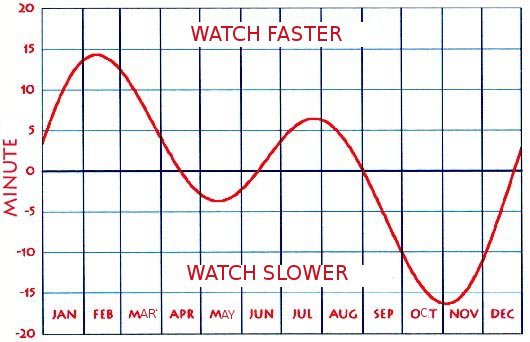

Unfortunately, the mean time shown by a clock and the true time shown by a sundial don’t agree throughout the year. Because the earth’s orbit around the sun is elliptical and because the earth’s axis is tilted to the celestial plane by 23 ½ degrees, the sundial (showing apparent or true solar time) and the clock (showing mean solar time) can be different by as much as 15 minutes.

There are four days in the year when the clock and the sundial agree with each other – 15th April, 13th June, 1st September and 25th December.

Until 1657 and the introduction of the pendulum, real time didn’t matter much as clocks were so inaccurate that the variations between true and mean time were irrelevant to all except astronomers.

The application of the pendulum to clocks made them capable of much more accurate timekeeping and the same was true when the balance spring was added to the watch in 1675 – measuring time to within a minute a week.

So, in order for an owner to put his clock right by a sundial, he had to know what the difference should be between his sundial reading and the time shown on his clock.

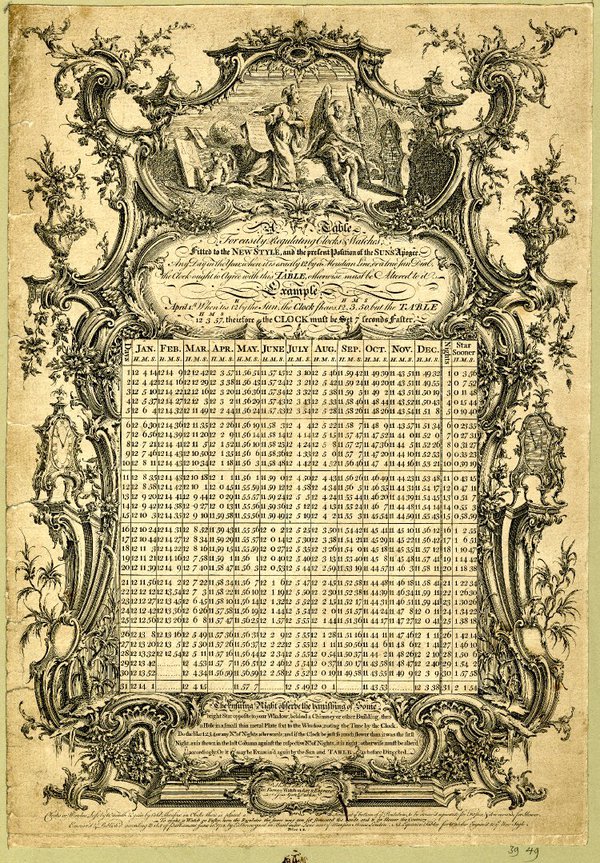

From the latter part of the seventeenth century, tables were published which gave exactly that information. The table shown here is devised so that when a clock is checked at noon, the table shows what time the clock should show.

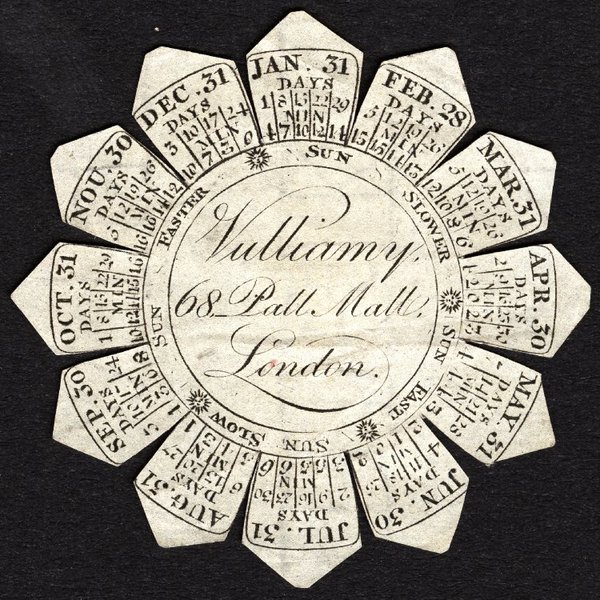

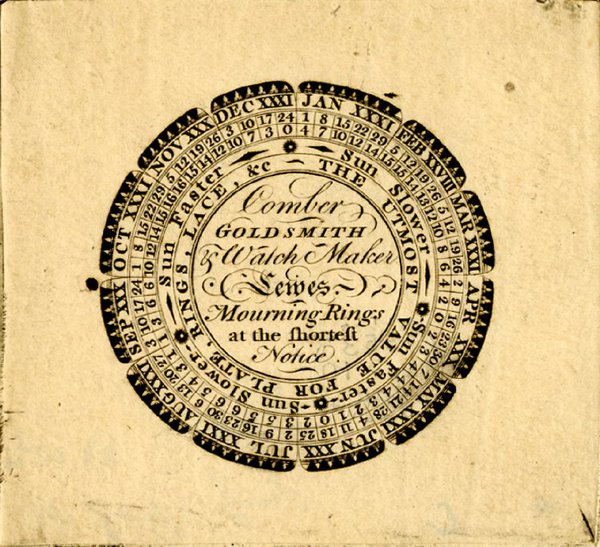

From the later part of the 18th century watchmakers would add a circular advertising paper into the outer cases of pair-cased watches and many of these had the equation-of-time table printed on them for easy reference.

Such papers were produced by top London makers such as Vulliamy in Pall Mall and by provincial makers such as Richard Comber of Lewes in Sussex. It was probably Comber’s customers who needed a table more than someone in the centre of London where the church bells offered a huge variety of ‘right’ time. It is worth bearing in mind, too, that the adjustments could only be done when the sun was shining!

Freak control

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Continuing our wander through the five elements, we come to the controller – the part of the clock which controls its rate. Let us pass-by the major landmarks (the pendulum, the balance spring and wheel and the quartz crystal) and seek an alternative trail.

With their origins preceding mechanical clocks, compartmented cylindrical clepsydrae (shown in a previous post for their silent operation) have a drum which rotates and descends. Water passes between compartments inside the drum, controlling the rate of rotation.

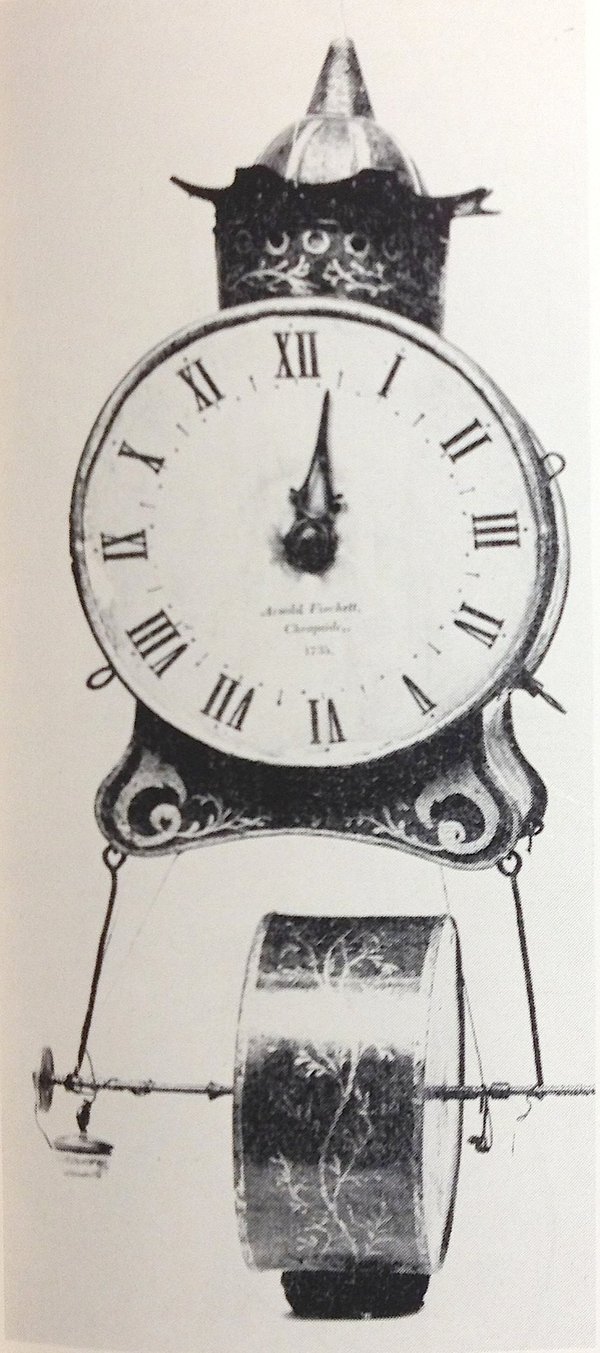

These were recurrently popular at various times in history and were incorporated in clocks, such as the example illustrated here which was made by Arnold Finchett, London, c.1760. The drum, connected by a line, drives the hand on the dial. This system is reported to provide reasonable timekeeping (at least in non-freezing conditions)!

Sir William Congreve (1772-1828) patented his inclined-plane rolling-ball clock design in 1808. Its ball bearing zigzags down a track on the table and actuates a lever at the end of its travel, causing the table to see-saw and the ball to roll back again.

In the example illustrated here, each leg takes thirty seconds. Despite being largely detached from the influence of the movement, the progress of the ball is hampered by any irregularities on the track, generally resulting in awful timekeeping (rather like my daily commute).

Nevertheless, the clock is mesmerising and surveys show that it retains the attention of visitors longer than any other exhibit in Djanogly horological galleries.

Another clock shown before is the Smiths “Sectric” electric mantel clock. The clock motor is synchronous – i.e. its speed depends on the (very stable) frequency of the alternating current of the mains supply, which thus effectively controls the rate of the clock.

These clocks were very popular from 1930s but were superseded by quartz technology from the late 1960s, largely for the convenience of battery power, which avoided the need for wiring.

Finally, from 1960 Bulova produced their 'Accutron' watches which incorporated a tuning fork to control their rate. The steady hum of the tuning fork can clearly be heard when the watch is held to the ear.

Despite being excellent timekeepers and very popular, within ten years the introduction of superior and cheaper quartz watches rendered them obsolete.

Falling back

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

It’s that time of year again when our faithful timekeepers quiver, for fear that we will ignore the advice of the clockmaker and attempt to turn the hands backwards, as we return to daily life punctuated by GMT (or UTC if you prefer) on Sunday.

I think it is fair to say that the majority of us are more sympathetic towards the autumnal adjustment, as we can luxuriate in the hour that was ‘banked’ in the spring, so perhaps now is the ideal time to bring this discussion to the AHS blog.

Today, internet searchers will find that the energetic equestrian builder from Petts Wood, William Willett has been eclipsed as the architect of Daylight Saving Time (DST) by George Vernon Hudson, the English born New Zealand entomologist, who first proposed his scheme to the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1895.

In England, thanks to Willett’s monumental efforts, the Daylight Saving Bill was presented before parliament in 1908 and it offered that ‘for a period of 154 days, an increase of sixty minutes more sunshine in the evening of each day’.

The then President of the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill astutely noted in the margins of his copy that this was an ‘optimistic view of our climate!’

Despite Churchill’s support the Bill did not pass and it was eight years before Daylight Saving was introduced as a wartime economy pre-empted by its earlier implementation in Germany.

This Sunday, as you pause the pendulum on your antique clock, will you follow Winston Churchill’s lead and ‘raise a silent toast to William Willett’ and perhaps reflect on the 154 hours of extra ‘sunshine’ that you enjoyed this year?

Conservation and repair of a mystery clock

This post was written by Kenneth Cobb

A disassembled glass and ormolu mystery clock was sent to West Dean College from overseas to be reassembled. A simple enough request, however the 1850’s mechanical mystique of smooth running remained a challenge throughout the three month process.

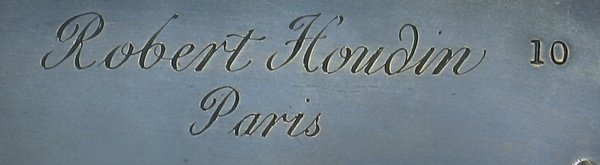

The clock was made by Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. Born into a family of watchmakers in Blois, France, he was primarily a conjurer and practical joker and this clock is no exception as it is Robert-Houdin’s ‘Fourth Series’ of Mystery Clocks. Onlookers would have wondered at the science of telling the time without the hands being attached to conventional clockwork.

One of West Dean’s key strengths is that conservation departments work together, thus the glass was cleaned by students in the Ceramics Department and advice on cleaning the ormolu was supplied by the Metals Department. Typical of the West Dean conservation approach is Robert Houdin’s signature in copper plate writing on a plate, which was left with the patina as received since it is stable.

The movement itself was a challenge as previous repairs had probably exacerbated its primary weaknesses: the plates are long with a minimum number of pillars to support the tensions of twin sprung barrels thereby making the movement unstable. The lead-off work was hidden within the body of the object. There were so many interconnected links that it was not clear which connection or link was at fault: a question that took weeks to resolve.

Finally, the clock ran reliably and sadly had to be returned as it was a considerable source of interest. As a student, the clock was been a privilege to work on having been a great source of learning and patience, and under the tutorship of Matthew Read and Malcolm Archer I have gained a lot more understanding and confidence in this field.

Can we sex-up the time-recorder?

This post was written by James Nye

We’re used to seeing Hollywood actresses, the latest haute horlogerie on their wrists, gazing at us in dreamy soft focus. But what about the advertisers looking to push horlogerie industrielle?

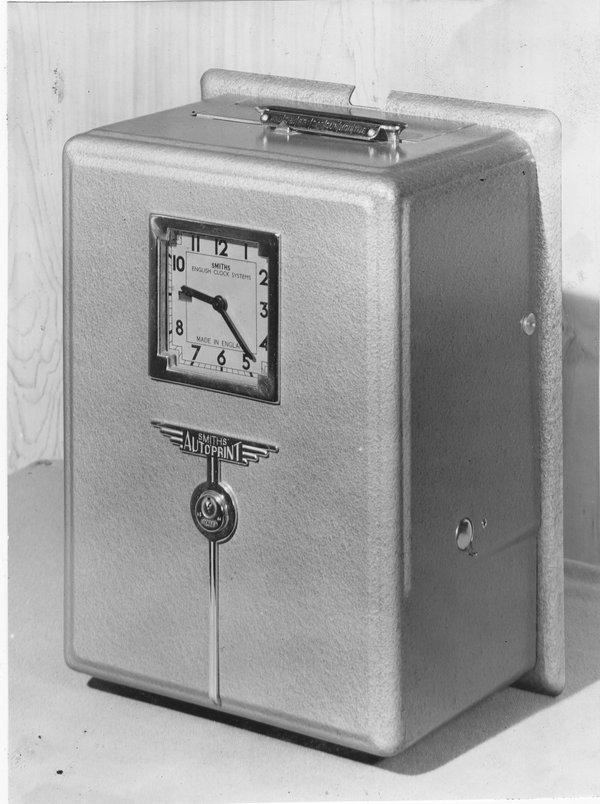

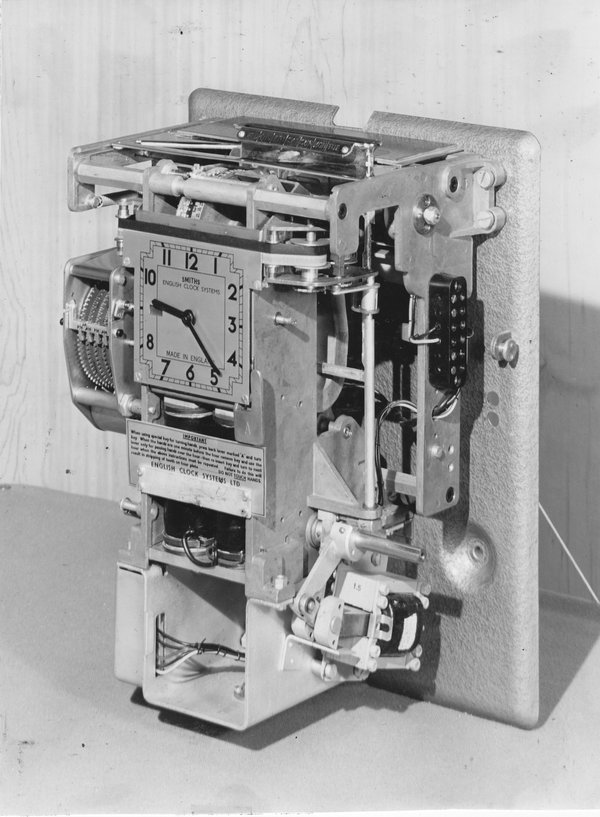

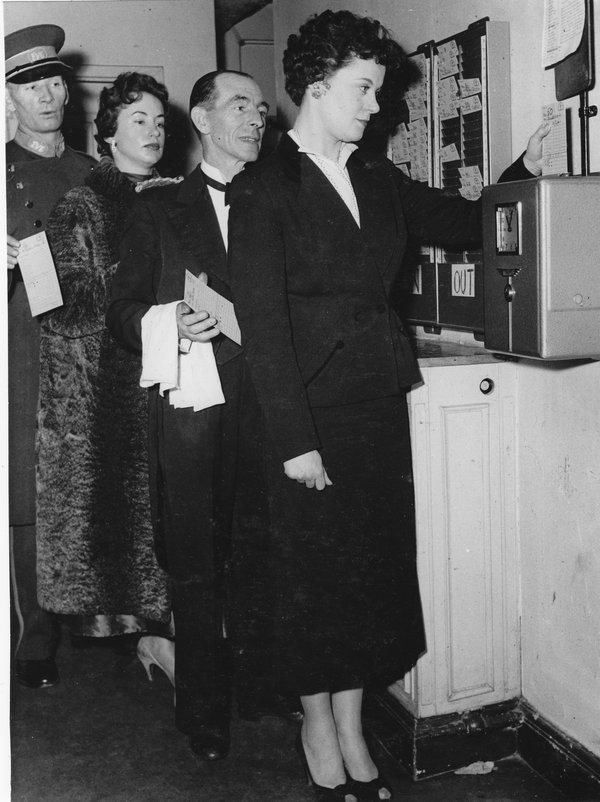

In an earlier blog I presented some pictures from inside the English Clock Systems (ECS) works at King’s Cross from the early 1950s. One of the shots showed the production line for the time recorders. The final product – the Autoprint – was a superb machine, and here are a couple of shots, showing both the mechanism and the outer casing.

The problem facing the ECS publicity unit was how to make the machine a bit more interesting in a catalogue or journal report. Watches and exotic locations were one thing, but the time recorder presented a bit of a challenge on the face of it. In this blog I speculate on the thought process of the lads as they set to their task.

The Autoprint was proudly on show at the 1956 British Industries Fair. The display stand was duly photographed, but an attraction for businessmen that year was a trip to the Eve nightclub on Regent Street. Our intrepid team tagged along, and lo and behold, the nightclub staff used an Autoprint!

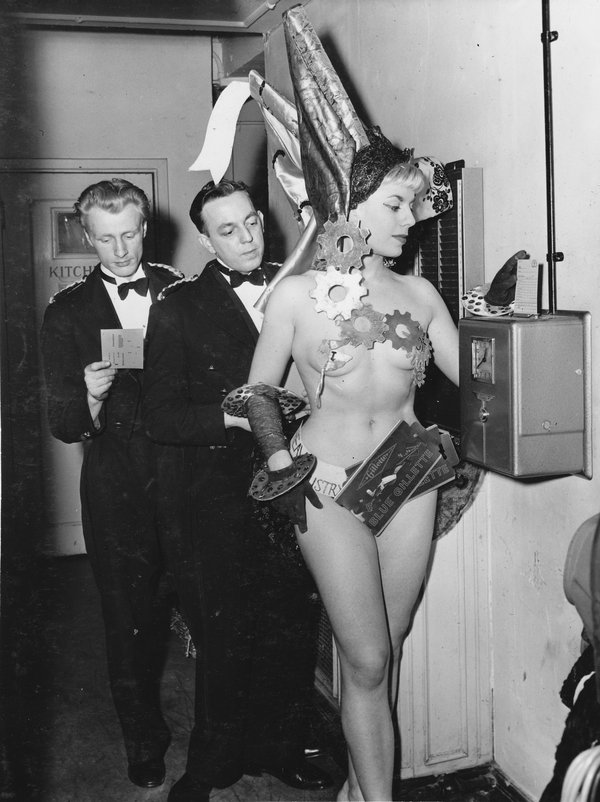

A first shot caught the commissionaire and other colleagues stamping their cards, but patience was rewarded with the arrival of a hostess, happy to pose.

Finally, of course, the show-girls themselves arrived – all adorned with representations of items manufactured in Britain. The third image shows Gillette-girl!

Picture Post (7 January 1956) carried a double-page spread on the cabaret, illustrating different industries from the BIF, but the historic industrial horological shot shown here remained hidden in an archive until I stumbled across it recently. In the interests of scholarship I felt it should be published.

A silent turret clock at the V&A

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum who notice the turret clock high up in the entrance hall find no explanatory label. Fortunately there is detailed information on the V&A website.

The 8-day turret clock with hour striking was ordered in 1857 for the newly created South Kensington Museum, as it was then named. It was made by J. Smith and Sons of Clerkenwell and cost £150: £110 for the clock and £40 for the bell and fittings.

A duplicate of the clock was later made by the same firm and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1862 (held on the site of the present Natural History Museum), where it gained a prize medal.

The two dials were designed by the artist Francis Wollaston Moody, who decorated much of the museum, and show allegorical figures.

Day, in a chariot, is followed by a cloaked female figure representing Night; below it is the figure of Time with his symbols: hourglass and scythe. The irrevocability of time is represented by the letters of the word IRREVOCABLE spaced out between the Roman numerals.

To see it properly you need binoculars, but the photos reproduced here – as good as I could manage with a simple camera and amateur skills – give an idea of what the clock looks like.

In 1951 the clock was stopped and silenced, as it was cumbersome for a clock-winder to climb up a ladder, and the booming bell was thought a nuisance for the visitors. Later it was taken down and stored away.

But in the early 1980s it was put back in place, as it was considered an interesting object in its own right, and because of its association with the early history of the museum. It has been converted to electricity, so it shows the correct time even though the pendulum with its heavy spherical bob hangs motionless. But the bell remains silent.

'A Visit to the Science and Art Museums'

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1932, the Trinidadian historian and writer, Cyril Lionel Robert (C.L.R.) James, then aged 31, visited the Science Museum in London.

'I hadn’t intended to spend much time there', he wrote. 'I was on my way to the Victoria and Albert Museum. But one of the men I was with, John Ince, is clever at engines and, at least to an ignoramus like myself, learned in the mysteries of mechanics. He persuaded me to go in and, I do not know why, the place had a surprising effect on me.'

The museum had only been open in its present building on Exhibition Road for some five years when James visited. He was, as he described, 'knocked silly' by the sight of a racing seaplane in the front hall, 'one of the most beautiful things I have seen in London.'

But after James had viewed the Science Museum’s aircraft collection, he made his way to the time measurement display and stood gazing at the huge clock from Wells Cathedral, constructed in 1392 and moved to the Science Museum in the nineteenth century where, he observed, 'it ticks serenely on, striking the quarters and the hours, and keeping much better time than the brand-new watch which I bought two weeks ago'.

Standing in front of this iconic clock, James was struck by a feeling of mortality. 'I had a good look at that old clock', he remarked. 'I couldn’t help remembering with envy that in a few years I would probably be gone, while the old beast would probably be there in a thousand years, tick-ticking away, living his narrow but peaceable life.'

It was not until 1989, 57 years after his visit to the Science Museum’s clocks gallery, that C.L.R. James finally passed away, aged 88, in a small flat in Brixton. He had achieved many great things in his momentous life. But he was right: the Wells Cathedral clock keeps on tick-ticking at the Science Museum, over 600 years since it was first set going. And it still offers attentive visitors pause for thought, as it did in 1932.

Turret clock specialist Keith Scobie-Youngs will be speaking about the Wells Cathedral clock (together with other ancient timekeepers) at the AHS London Lecture Series on 20 March 2014. Check the AHS website nearer the time for more details.

Wake up – tea’s up

This post was written by David Thompson

What a treat to be able to wake up in the morning to a ready-made cup of tea and to be grateful to a machine for producing it automatically. Many of the older generation will remember a machine for just that purpose, a machine which was always referred to as the Teasmade.

Probably the one we all remember was the Goblin Teasmade but there were many others and the originally idea has its origins at the end of the 19th century with Mr. Rowbottom’s 1891 patent – with an automatically lit gas burner to heat the water in the kettle and then the machine would pour the boiling water into a tea-pot to make the tea, I can just see the warning notice on such a machine today – well not really as such a fire hazard would not be put into manufacture today.

There is a fine example of an Albert E. Richardson machine in the Science Museum to give an idea of what the early machine were like.

I was intrigued by this subject from seeing the Teasmade on exhibition in the British Museum clocks and watches gallery and it lead me to a splendid account of the history of the automatic tea maker written by David Stoner and published as a chapter in Clifford Bird’s book on Metamec, published by our own society and still available today at a give-away price.

All the original machines were clockwork, controlled by a simple alarm clock mechanism so you got the wake-up bell and the ready-made cup of tea, almost guaranteed to be luke warm. Many people swore by them and I don’t doubt at them. Nevertheless, a great idea.

Time and efficiency

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Last time I looked at how clocks and watches obtain and store their energy, but I thought it worth mentioning how carefully they use it.

Some clocks are designed to have a surfeit of energy – for instance turret clocks must be able to overcome ice and snow loading. But, in general, efficiency is paramount in horology.

A 17th century eight day longcase clock typically runs on a 12lb weight (5.44kg in new money) which drops about 5 feet in the eight days. Based on those numbers, my dimly recollected school physics tells me that such a longcase clock must use about 1/8500th of a Watt of power.

Let us compare that with something familiar. The best example I can think-up is the motor that vibrates a mobile phone – these run at about 0.16W – i.e. that little motor that tickles in your pocket could run about 1500 longcase clocks. Or, looking at it another way, the energy used to boil an egg would keep a longcase clock going for 80 years. Not bad for a 300 year old machine.

The Atmos clock (which I mentioned before for its ability to be powered by changes in air temperature) is in another league – the little mobile phone motor could run 700,000 of them. 1 boiled egg, 38000 years.

How are they so much more efficient than the longcase clock? Apart from being closer in scale to watch work, the Atmos clock benefits from 250 years of horological development. They are factory made, not hand made – this facilitates much closer tolerances and optimal gear tooth shapes. Like fine watches, their bearings are jewelled (jewels are little rubies with holes drilled in them – very smooth and very hard wearing). They also have a steel torsion pendulum which is excellent at conserving energy.

Something else to bear in mind is that we expect our clocks and watches to run non-stop for years on end, between services, without breaking down. Do you ask the same of your car? Remember that when your clock repairer presents their next bill to you!

Home time

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

As next year’s AHS conference will be shaped by the theme ‘Military Time’, it seems appropriate that this post should follow the military theme and by chance, as with David Read’s recent post, it includes a radio.

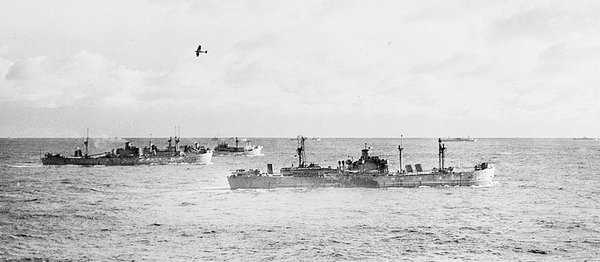

There are two HS.4 navigational watches in the National Maritime Museum collection, both retailed by the firm H. Golay and Sons, which were used by the Fleet Air Arm in Fairey Swordfish aircraft during WWII.

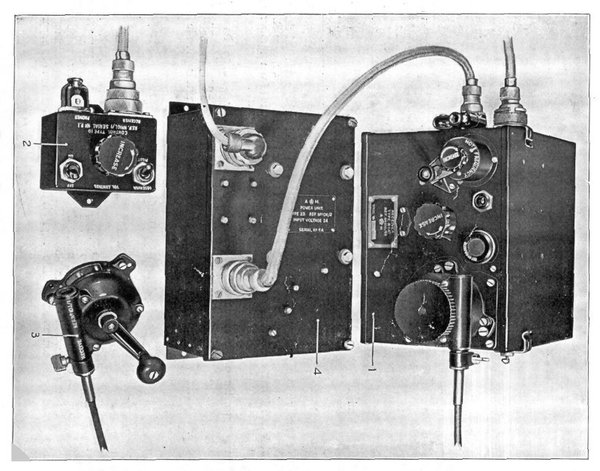

We learn from the 1941/1942 Admiralty Manual of Navigation that these watches were known as beacon watches and that they were only to be used in aircraft fitted with an R1147 radio receiver.

The carriers were equipped with a revolving beacon that continuously transmitted second pulses, making a full rotation once per minute. The crucial feature of this system was that the beacon emitted a different sounding signal when it was pointing due north. Prior to launch (these planes were catapulted into the air) the observer would tune the radio receiver to the beacon and set the bezel of the watch so that zero on the outer scale and the tip of the second hand align precisely at the time of the northern signal.

When returning to the carrier, the observer on board the aircraft would turn on the radio and listen to the beacon’s signal. The strongest reception would be experienced when the beacon was pointing directly at the aircraft and using the watch, the aircraft’s position relative to its carrier could be found and the pilot given the course to take.

If we take the watch shown above, for example, as indicating the moment of the signal’s maximum intensity, the aircraft’s position would be approximately SSW of the carrier. The primary benefit was that these slow aircraft could home in on their carrier from up to 100 miles away without sending out radio signals that may betray their position to the enemy.

This ingenious horological adaptation helped to save lives and is just one example of innovation necessitated by war that could be explored at next year’s conference.

If you feel that you can contribute a talk that would fit ‘Military Time’ theme, you are invited to contact the AGM lecture coordinator, Rory McEvoy, Curator of Horology, Royal Observatory Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SE10 9NF, e-mail: RmcEvoy@rmg.co.uk. Papers could explore technical horological development as well the wider implications for both civil and military timekeeping. Please note that the theme is not limited to the First World War, and that the military of course includes the ground, sea and air forces.

When is a wrist watch not a watch?

This post was written by David Read

In February 2013 it was leaked that Apple was experimenting with an iWatch. However, six months later and at the time of writing this blog there is still no news from Apple and the technical press is now guessing that the project has hit battery problems.

If only Dick Tracy, the famous cartoon sleuth, was still around to find out what the bad guys are up to and get at the iWatch facts. Tracy had sported a remarkable watch on his wrist since 1946 and now, 67 years later, Time Magazine described that watch as 'the most indestructible meme in tech journalism'.

For decades now, it has been nearly impossible to write about communications technology combined with a wristwatch without invoking the plainclothes cop with a special watch on his wrist who first appeared in 1931, even though the days when one could follow Dick Tracy’s adventures in a daily newspaper have long gone.

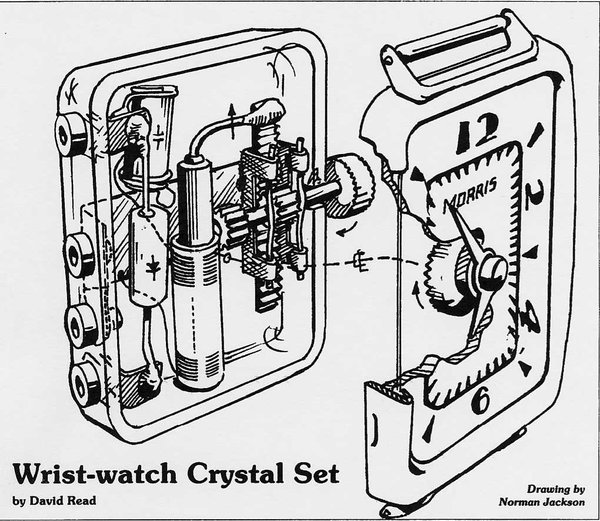

Popular science fiction is always years ahead of the technologies that turn dreams into reality. However developments in solid state electronics had, by the 1940s, enabled the large galena and cat’s whisker detector of the crystal set to be produced as a tiny point-contact diode and placed inside a wrist watch case as in the Morris watch shown here.

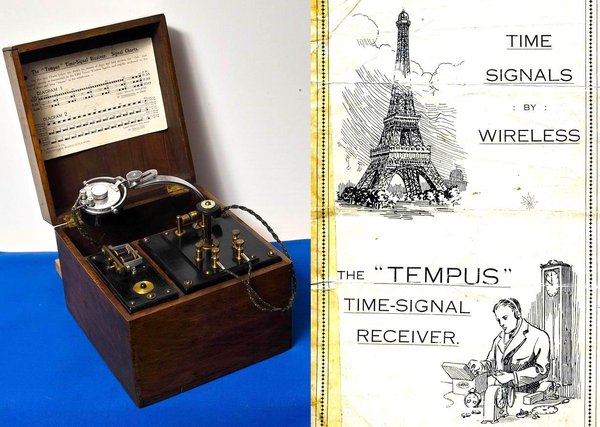

But is this a watch? No, it’s a crystal radio. However, horology and radio have a long shared history involving frequency and time. This clandestine wristwatch radio can receive time signals in exactly the same way as mariners and watchmakers did from 1912 in order to check their chronometers, clocks and watches against the timecode transmitted from the Eiffel Tower. My image of the Tempus crystal radio and instructions sets the scene.

The illustration of the Morris watch shows a standard-sized watch case made of chrome-plated steel. The dial, signed Morris, is in typical 1940s style. The standard of manufacture is high and the disguise on the wrist is perfect. The case back is made of moulded Perspex to provide an insulated chassis on which the circuit can be built without special measures to insulate the components, aerial, earphone sockets and associated wiring.

The winding button is actually a dial knob and connects to a rack-and-pinion control of tuning in which an iron-dust core is moved within the aerial coil and tunes the required frequency by altering the coil’s inductance. This assembly is connected to the earthy end of the coil and also to the metal case thus providing a body earth to stabilize the circuit whilst tuning. A tiny sealed point-contact crystal detector is enclosed in an evacuated glass tube and a capacitor across the coil completes the circuit.

A second pinion on the winding stem connects with a crown wheel on which the hands are mounted. This alters the position of the hands on the face of the watch and provides a scale against which a station can be memorized or noted. Using the wrist watch crystal set in conjunction with a deaf aid as an amplifier would have allowed the use of a short aerial such a bedstead and completed the disguised operation.

The drawing was made for me in the 1980s by my late dear friend Norman Jackson, an outstanding engineer and artist whose illustrations always showed at a glance how things work; something that photographs can never match.

It is interesting to speculate why such a radio was made and I have never seen another. However, the Morris watch cannot be unique because it is a professionally designed object requiring bespoke production tooling and Perspex moulding facilities. The public market for such clandestine receivers would have been tiny and with no chance of recovering the costs involved. Without a consumer market for this item it would seem possible that it was funded by a government agency and the headline news today shows that such agencies are still active in the ancient arts of listening, spying, and gathering information.

And another thing – yes it does work!