The AHS Blog

Bomb found outside AHS meeting focused on bomb scares

This post was written by David Rooney

The strangest thing happened last Thursday. To be honest, I thought it was a put-up job and so did many of the people with me. I thought James Nye had arranged it; everyone else thought I had.

It was the first AHS London Lecture of 2017. We’re in a new venue this year. Following the success of last year’s programme things were getting a bit tight at Cannon Place and we needed a bigger room with space to grow, so thanks to an introduction from our Council Member James Stratton, head of the clocks department at Bonhams, we have been able to move to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) on Parliament Square, overlooking the Houses of Parliament and the Great Clock of Westminster.

I was the lecturer for our first meeting at RICS. I’ve been thinking a lot over the years about the political symbolism of time: how it stands for other things besides when to catch the train. So my talk last Thursday was about standard time and violent protest in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth.

Specifically, I was focusing on two bomb attacks: one on the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1894 by an anarchist and one on the Royal Observatory Edinburgh in 1913 by suffragettes.

Both attacks, I argued, were symbolic strikes against scientifically defined standard time but both were very real, resulting in loss of life at Greenwich and significant damage at Edinburgh. They were attacks on the establishment – an establishment centred at Westminster just a few paces from where I was speaking.

My talk finished bang on time at 7.15pm and I was getting ready to answer questions when the house manager came in and whispered a message to James, who was chairing the evening.

I assumed it was a minor problem with the catering laid on thanks to the generosity of sponsor Jonny Flower – maybe the prosecco wasn’t chilled enough or the hors d’oeuvres were running late. But I was wrong.

We’d all seen the flashing blue lights through the frosted windows of the lecture room, but they are not an unusual sight in Westminster and we thought little of it. Perhaps a car had been pulled over, or a tourist had taken a tumble. Certainly nothing out of the ordinary.

Then James interrupted proceedings to tell the audience that much of the area outside, including bridges and tube stations, was being sealed off by the police.

We really thought it was a put-up job when he told us that a bomb had been found by Westminster Bridge. It was not a false alarm. It was a real bomb – from the Second World War. It had been found by a dredger in the River Thames.

The police call to the Royal Navy bomb disposal squad went in at exactly 7.15pm – the moment I stopped speaking.

Don’t worry. Nobody was hurt in the incident and the bomb was safely detonated early the following morning at Tilbury. The March lecture is about the gold workers and enamellers of Geneva and we’re not expecting any bother.

How did Arnold get to the Clockmakers’ Museum?

This post was written by David Rooney

On 23 October, the Clockmakers’ Museum opened at the Science Museum. The new gallery is a treasure-trove of horological history, home to so many wonderful items it’s hard to know where to look next.

Tucked away in one showcase is a modest-looking pocket watch that would be easy to miss, yet tells a story close to my heart—that of Ruth Belville, whose biography I wrote in 2008.

The watch was originally the property of John Belville, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, who used it between 1836 and his death twenty years later to carry accurate Greenwich Time round a network of subscribers across London.

When John died in 1856, the watch was passed to Maria, his wife, who continued carrying it round London until 1892, when she retired.

She then passed it to her daughter, Ruth, who named it ‘Arnold’ after its maker, John Arnold. Ruth carried the time to town with Arnold until 1940, when she retired, aged 86.

But it was not the end of the line for Arnold. Ruth had always wanted it to have a good home.

‘When it retires from business … I think the dear old thing ought to be put in the British Museum’, she told the Evening News in 1908. In 1921, Ruth changed her mind, stating that she ‘should wish the Royal Observatory to have the first offer of purchasing my chronometer’.

Yet neither received Arnold.

In 1941, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers granted Ruth a pension which gave her crucial financial security in her retirement.

Ruth repaid its generosity in January 1943, when she wrote to the Company offering her watch for its museum when the time came. The Company accepted, noting that ‘by doing so her name would be perpetuated for all time’.

Eight months later, Ruth died with Arnold by her bedside. The watch was duly transferred to the Company’s collection and ended up on display at Guildhall.

Now I needn’t go to Guildhall to see Arnold—delightful though my visits there always were—but instead I can pop into the magnificent new gallery at the Science Museum during my lunch break.

I hope you’ll have a chance to see it too.

The AHS 2015 Annual Meeting

This post was written by David Rooney

We welcomed over 100 members and guests to a packed full house at the National Maritime Museum for our 2015 Annual Meeting last Saturday. The sun shone, the atmosphere was buzzing, and we were given a superb day of talks and conversation.

The theme this year was ‘time and transport’ and, outside the museum, AHS members had brought a stunning selection of vintage cars to help set the scene.

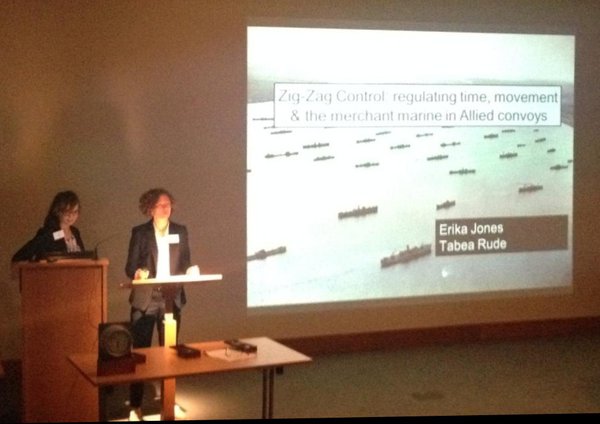

During the morning session, we had fascinating talks by Peter Burt on RGS explorers’ watches; Tabea Rude and Erika Jones on zig-zag control; and Rory McEvoy on a Perregaux advertising campaign (apologies for the poor quality indoor photographs!)

After lunch and the society’s AGM, we heard from our new President, Lisa Jardine, on sea-going clocks; Jonathan Betts on polar expedition chronometers; and James Nye on the history of car clocks.

We were delighted to learn that Professor Jardine has recently been made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society.

We also marked the handover of the chairing of the society from David Thompson to James Nye by seeing David awarded a Fellowship of the AHS. Our huge congratulations and thanks to Lisa, David and James.

It was great to see so many members and guests from all around the country, of all ages and with all sorts of interests—represented also in the wonderful variety of speakers and lectures.

Thanks to you all for coming—and we look forward to the coming year with great excitement!

Changing times in Germany

This post was written by David Rooney

We call it British summer time, but the first country to advance its clocks during the summer was Germany, which inaugurated a daylight-saving scheme in April 1916.

A letter, written 100 years ago this week and found buried in a museum archive, holds an important clue as to how the idea reached the top of German government just days before the outbreak of the First World War.

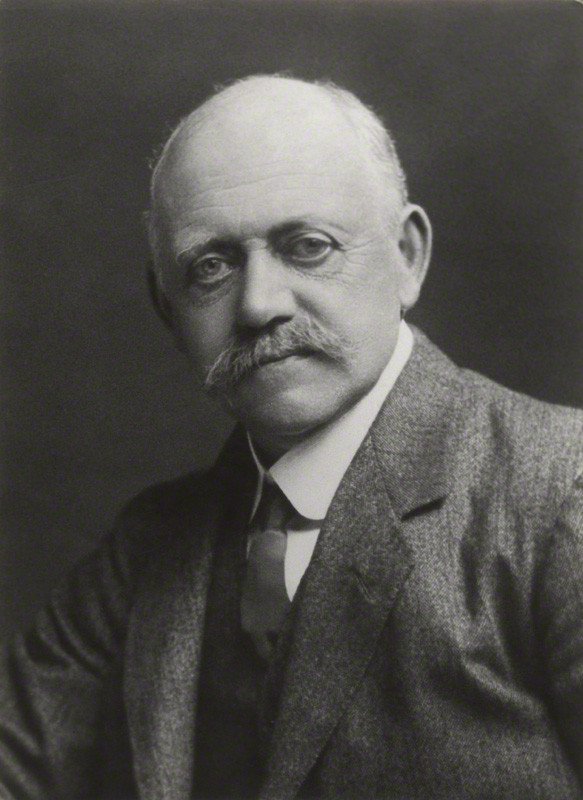

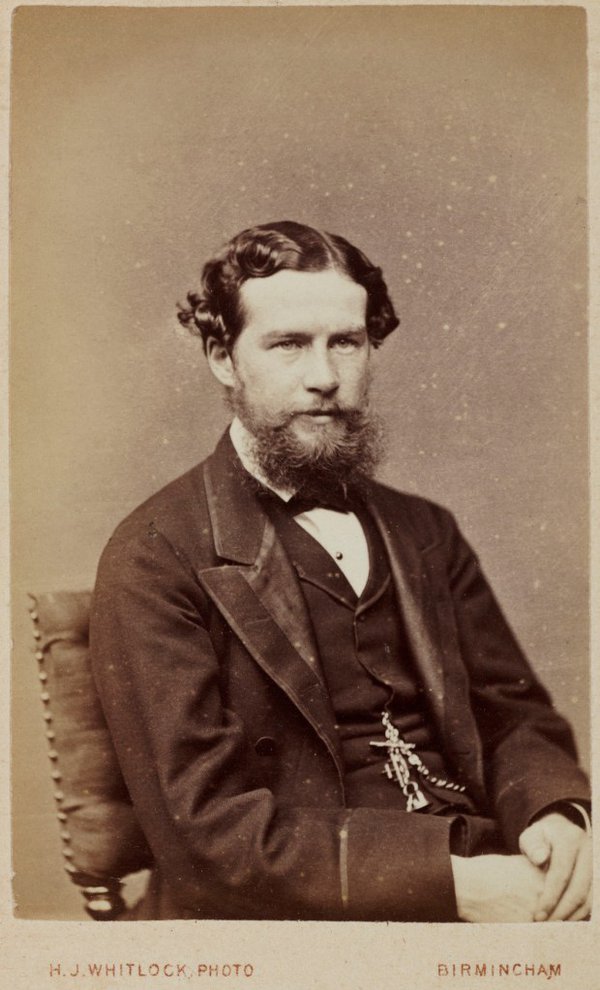

The champion of daylight-saving, British house-builder William Willett, had spent many years campaigning around the world for his time-shifting scheme to be adopted, and had become a regular correspondent with Henry von Böttinger, a prominent German chemist and industrialist who had been appointed to the Prussian House of Lords in 1909 by the German Emperor, Wilhelm II.

In 1913, von Böttinger had written to Willett to say that he was 'still pushing the Time Saving Question' and had raised the matter with the Prussian Minister of Public Works and the Association of German Chambers of Commerce.

But it was on 21 June 1914 that von Böttinger wrote again to Willett, this time with news that he was about to take the daylight-saving proposal to Germany’s highest authority.

'I have meantime taken note of your wish to have the subject laid before the German Emperor—and as His Majesty knows me personally and very well, I have at once made a written report to him and have asked him to devote his interest to the furtherance of this great object. As soon as I have another personal interview with His Majesty I shall not fail to bespeak the subject with him and thus bring the matter still closer home to him.'

Seven days later, Kaiser Wilhelm’s friend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated, and Europe began its plunging descent into war.

This was the last letter William Willett received regarding his international daylight-saving campaign, and a few months later, while on a business trip to Spain, he contracted influenza and died.

We will never know the full circumstances of Germany’s adoption of daylight saving time in 1916, but it is possible that this letter between two influential international businessmen represented the crucial turning point in Willett’s campaign—though it was a campaign he did not live to see realized.

What is certain is that technology and politics are inseparable: ideas need powerful backers, and the German Emperor in 1914 was truly one of the most powerful men in the world.

The AHS Annual Meeting 2014

This post was written by David Rooney

On Saturday 17 May, 120 AHS members and guests packed into the National Maritime Museum’s lecture theatre for our 2014 Annual Meeting. It was a sell-out crowd, and what a day we all enjoyed.

Those who couldn’t make it missed a couple of important announcements which I’ll pass on here in advance of them appearing in the next Antiquarian Horology .

The first announcement came from Sir Arnold Wolfendale, the 14th Astronomer Royal, who has been a tireless supporter and champion of the AHS since becoming our President over 20 years ago.

Sir Arnold, whose inspiring and lively lectures on cosmological aspects of timekeeping have been enjoyed by so many of us over the years, has decided to stand down. We wish to thank him hugely for all of his support over the years and wish him well in his ‘retirement’ from the presidency.

David Thompson then announced that Professor Lisa Jardine, the eminent historian, writer and broadcaster, has agreed to become our new President, and takes over immediately.

Lisa is teaching this term at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (home of the recent Time For Everyone symposium), and could not be present in person, but she sent her best wishes and looks forward to meeting us in person in the near future.

We are delighted and honoured to welcome Lisa to the AHS presidency.

The other major announcement of the day was the launch of the brand new AHS website. We urge you to take a look. It is the culmination of many months of patient work by a small AHS team plus our designers, Latitude, and our web developers, Blanc, and has been fully funded by a donation from council member James Nye.

At the heart of the website is a remarkable new resource for AHS members. We have digitized the entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, and every single page we have ever published, dating back to the first issue in 1953, is now available and searchable online.

We are thrilled to bring this invaluable resource to members and wish to thank our great friends and technology partners, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in Germany, for carrying out the scanning and indexing work at an extremely preferential rate.

You can find the new website at our usual address, www.ahsoc.org, and to use the digital journal, simply log in to the members pages with the password printed on the back of your AHS membership card.

The addition of the journal archive is an extremely valuable new member benefit which must surely be worth the AHS subscription alone, so do please encourage your friends, colleagues and clients to join (don’t forget that you can join online using credit cards, debit cards or PayPal in just a few easy and secure clicks).

A tiny housekeeping note. The AHS blog on which you are reading this post has now moved to blog.ahsoc.org. The old address will still work fine, but if you subscribed to posts using an RSS feeder, we’re afraid you’ll need to re-subscribe from the new location. Sorry about that.

British Pathé films on YouTube

This post was written by David Rooney

In the latest in what seems to have become a short series on easy-access digital resources, I bring news that British Pathé has released its entire historical newsreel archive of 85,000 films onto YouTube, the video-sharing website.

British Pathé has long allowed people to see its historical newsreel films on its own website, and the release to YouTube doesn’t bring any change to the company’s copyright policy. But the findability of these often remarkable films will now have greatly increased, which can only be a good thing.

I have used British Pathé films in my historical research and my professional work curating museum exhibitions for years now, and it is therefore like meeting old friends to watch films on the YouTube channel such as The Golden Voice, Time Please and Standard Time.

For those with wider interests, I’ve also been moved seeing Comet Inquiry again, which appeared in the Science Museum’s recent award-winning Alan Turing exhibition. One of the AHS’s founder members, Alfred Basil Brooks, together with his wife, were killed in this tragic air crash which occurred just months after the founding of the society.

I think this film archive is strong in two ways beyond its sheer breadth.

Firstly, it helps to put technological objects and ideas into social and political context, which is crucial in understanding why people make, modify, use and choose things. Objects never emerge fully-formed in a contextual vacuum.

The second strength of the films is the technical understanding they can offer those studying particular technologies. There’s nothing like the moving image to bring dynamic objects to life.

So there we are. Another great digital archive of work made even easier to use. And along those lines, AHS members should watch out for an important announcement in the next few weeks. We’ve been working on something pretty special and we’re about to be able to share it with you…

You can find the British Pathé channel at https://www.youtube.com/user/britishpathe. Search by clicking the little magnifying glass symbol in the middle of the page underneath the header image.

100,000 more free images

This post was written by David Rooney

When I got an email from the Wellcome Trust which began, ‘we have some very important news to announce’, it certainly got my attention.

And they were right: it is very important news indeed, and I’m delighted to share it.

In my last post I talked about the recent release of a million images by the British Library. Already I’ve heard from colleagues and friends who say they have found new evidence amidst its vast collections that is crucial to support their research.

The news from the Wellcome Trust is the same. As of January this year:

'All historical images that are out of copyright and held by Wellcome Images are being made freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This means that they can be used and manipulated freely, for commercial or personal purposes, so long as the original source is acknowledged.'

You can download high-resolution files directly from their website. There are 100,000 images dating from as early as 1000 BCE. You can even get advice directly from Wellcome’s team of researchers, should you be having trouble finding what you need.

Like many in the AHS, I’m interested not only in clocks and watches themselves, but how horological machinery gets embedded in other technologies. So I searched for ‘clockwork’ and, rather than showing you the clockwork trephine (not safe for suppertime), here’s a clockwork picture of an itinerant dentist performing an extraction in the early 19th century. Ouch.

Whether you’re into automata like this, or medical technology, or astrology or philosophy or geology or anything else related to stories of time and its material culture, you’re sure to find something here to delight.

As I said last time, image banks such as this are invaluable treasure troves of historical evidence for researchers, whatever your subject. Serendipitous browsing leads to new leads and new ideas.

Huge thanks to Catherine Draycott and others at the Wellcome Trust (as well as the British Library) for making such a bold and generous decision to open this to everyone.

A million free images

This post was written by David Rooney

Just before Christmas, the British Library released over a million historical images from its printed collections onto the image-sharing website Flickr. The images are out of copyright and the library has made them available with a Creative Commons licence which, in short, encourages anybody to use, remix and repurpose them, so long as they respect a few ground rules.

This is a remarkable resource of imagery and will be a boon for anybody carrying out historical research – such as AHS members.

There are countless images of interest in this release, each one of which might augment an existing research project or prompt a new one. The beauty of archives such as this is the opportunity for lateral thinking. You might be researching a particular village, or writer, or building, or period. And you might find an image here that opens up new avenues of research.

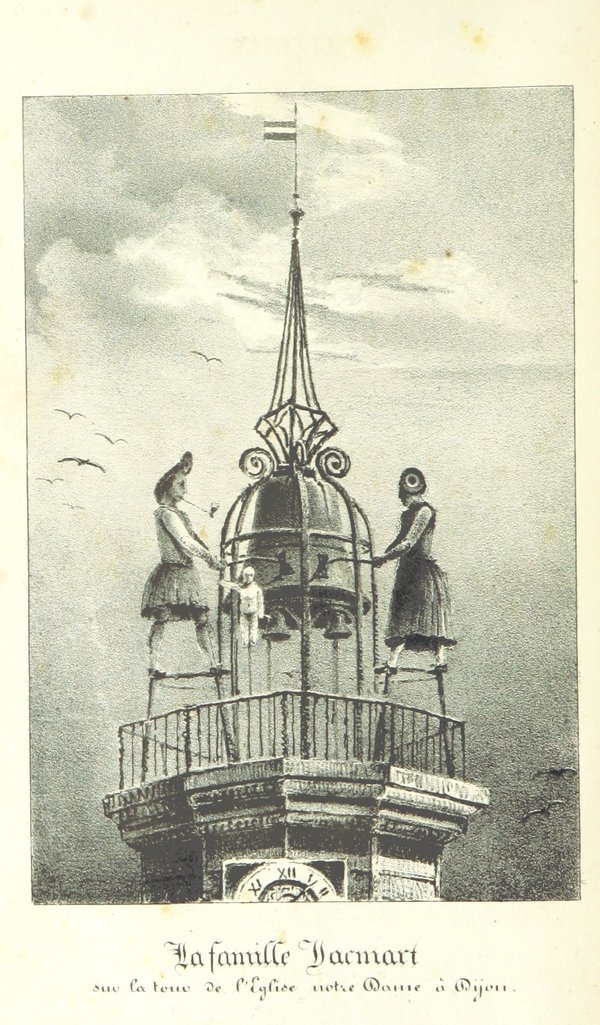

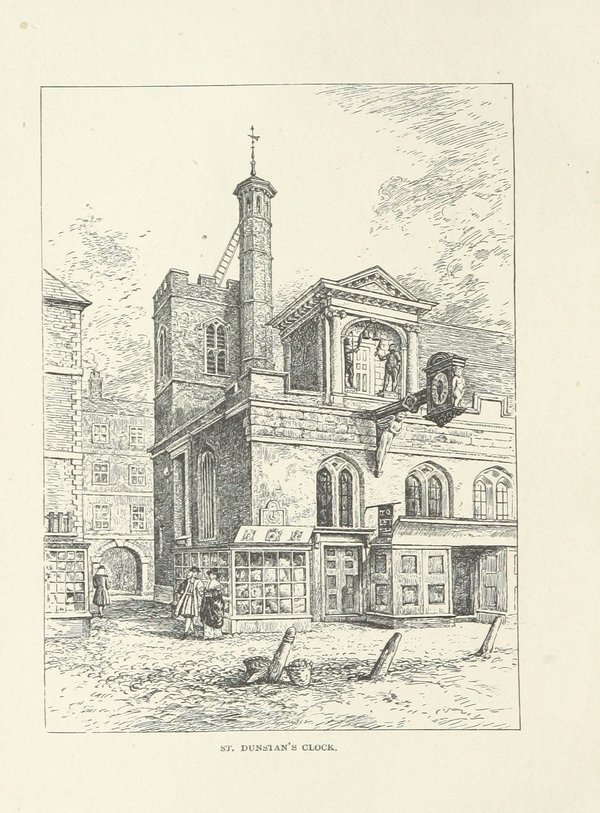

The first four images I found are the result of searching for ‘clock’ or ‘clocktower’ – as you’d expect, lots of public clocks.

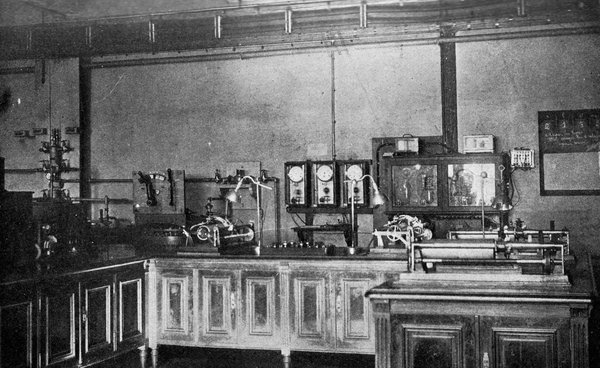

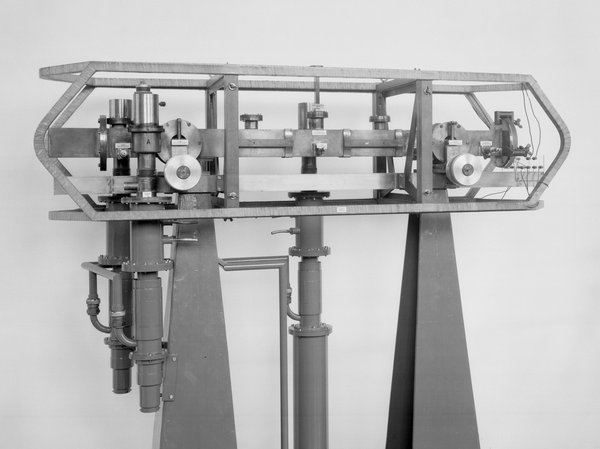

But let’s say I’m interested in chronometers. Unfortunately there are no search returns for that word. But then I tried searching for ‘observatory’, and found this image.

It’s from a book on the North Polar Expedition, and it’s a photograph of marine chronometers on show in a US Navy centennial exhibit in 1876.

That led me to this catalogue of the objects exhibited. And on pages 79–81 there’s a remarkable and detailed description of the use of chronometers at the US Naval Observatory in the 1870s. Serendipitous discovery is a wonderful thing.

You’ll probably want to put aside an hour or two browsing these images – and a lot more time following the interesting leads they throw up! Happy hunting, and happy new year.

'A Visit to the Science and Art Museums'

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1932, the Trinidadian historian and writer, Cyril Lionel Robert (C.L.R.) James, then aged 31, visited the Science Museum in London.

'I hadn’t intended to spend much time there', he wrote. 'I was on my way to the Victoria and Albert Museum. But one of the men I was with, John Ince, is clever at engines and, at least to an ignoramus like myself, learned in the mysteries of mechanics. He persuaded me to go in and, I do not know why, the place had a surprising effect on me.'

The museum had only been open in its present building on Exhibition Road for some five years when James visited. He was, as he described, 'knocked silly' by the sight of a racing seaplane in the front hall, 'one of the most beautiful things I have seen in London.'

But after James had viewed the Science Museum’s aircraft collection, he made his way to the time measurement display and stood gazing at the huge clock from Wells Cathedral, constructed in 1392 and moved to the Science Museum in the nineteenth century where, he observed, 'it ticks serenely on, striking the quarters and the hours, and keeping much better time than the brand-new watch which I bought two weeks ago'.

Standing in front of this iconic clock, James was struck by a feeling of mortality. 'I had a good look at that old clock', he remarked. 'I couldn’t help remembering with envy that in a few years I would probably be gone, while the old beast would probably be there in a thousand years, tick-ticking away, living his narrow but peaceable life.'

It was not until 1989, 57 years after his visit to the Science Museum’s clocks gallery, that C.L.R. James finally passed away, aged 88, in a small flat in Brixton. He had achieved many great things in his momentous life. But he was right: the Wells Cathedral clock keeps on tick-ticking at the Science Museum, over 600 years since it was first set going. And it still offers attentive visitors pause for thought, as it did in 1932.

Turret clock specialist Keith Scobie-Youngs will be speaking about the Wells Cathedral clock (together with other ancient timekeepers) at the AHS London Lecture Series on 20 March 2014. Check the AHS website nearer the time for more details.

Walking the ‘Willett Way’

This post was written by David Rooney

Every spring, when we put our clocks and watches forward for British Summer Time, we do so with a hollow laugh. March weather is rarely summery! But last month many in the UK have seen prolonged sunshine, and in London we’ve had a heat wave. Summer arrived at last.

If you like walking in sunny weather, and if you’re in London, you can combine a walk with finding out more about British Summer Time. It takes in Petts Wood and Chislehurst, home of William Willett, the schemes creator, and it’s easily accessible by public transport.

You can view the walk instructions online or print them off. But I must warn you that it’s a while since I prepared this trail, and things might have changed. Do take care and, if in doubt, follow your common sense, not my instructions! One thing that changed since I wrote the walk is the refurbishment of Willett’s grave, now looking superb.

It fascinates me that twice a year, every year, quarter of the population of the Earth changes its clocks and watches for summer time. That is a real, physical, close engagement between billions of people and billions of timekeepers each year across the globe—all because a Victorian British house-builder and moralist thought we should get up earlier in summer.

What this shows is the sheer power of clocks and watches to change and order human behaviour—or rather, the inventive ability of people to use time to control other people. We can see it all over the place when we know what to look for. Time is a political tool.

And that is one reason why you should join the AHS. Knowledge is power, and the more we understand timekeeping, the more we can understand the control that people exert on our lives using it. PS I’ve recently joined Twitter. If you’ve nothing better to do, you can follow me @rooneyvision.

Navigating the trackless seas

This post was written by David Rooney

If you stand on the Thames riverside near the East India dock basin, the view south is extraordinary.

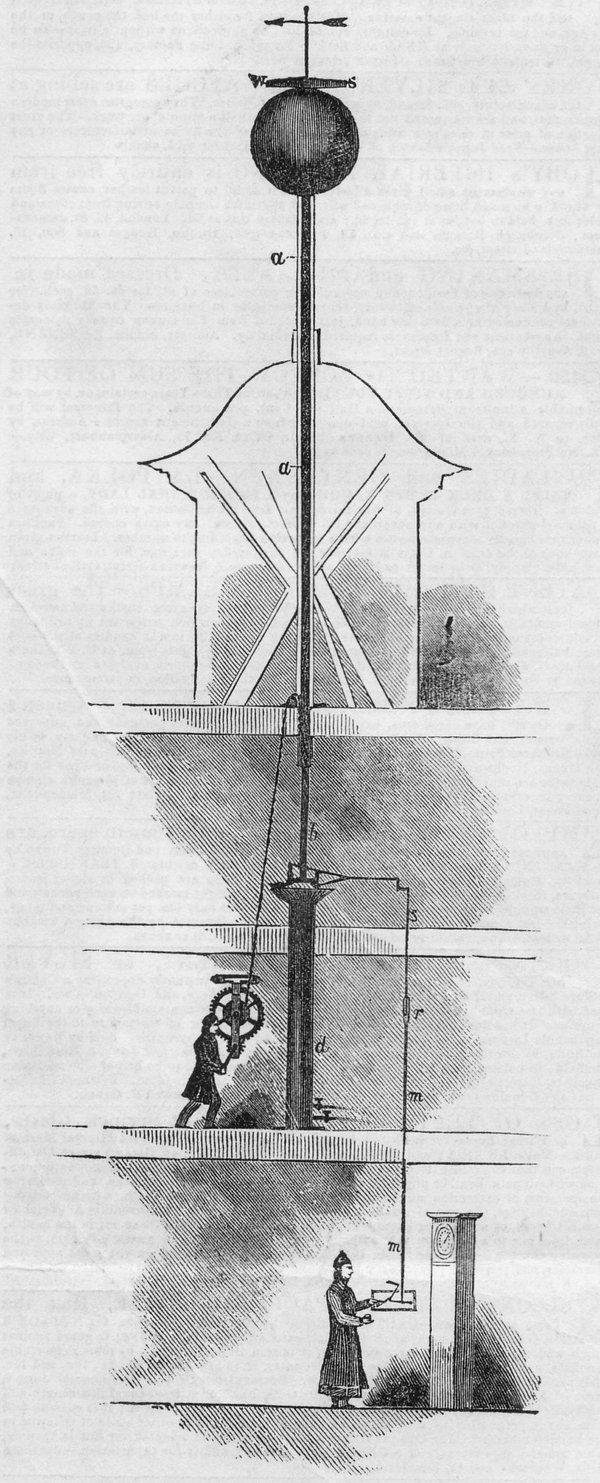

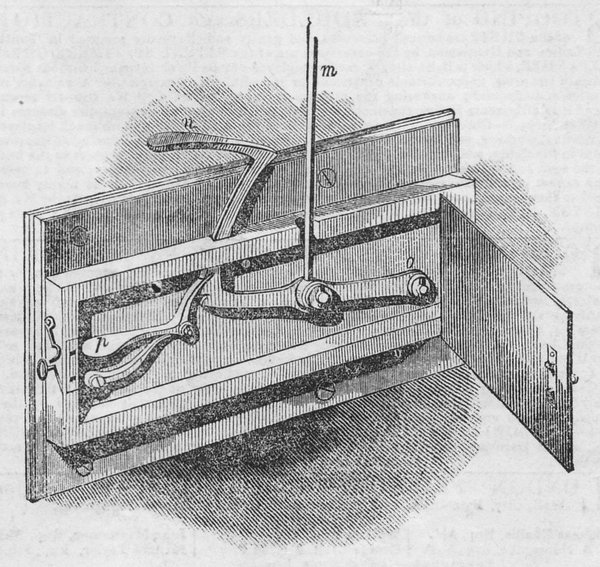

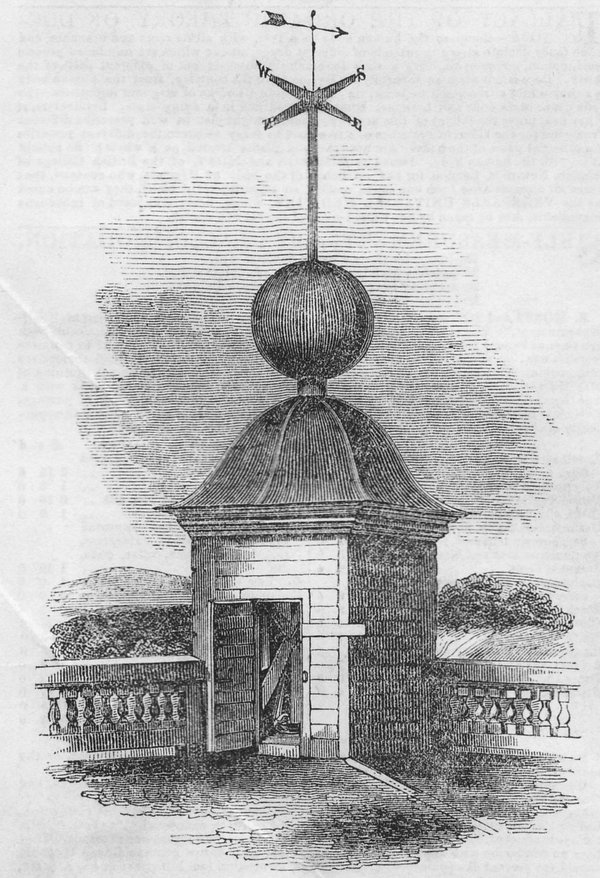

In the foreground is the remarkable structure of The O2, originally the Millennium Dome. But look further into the distance, and you’ll just make out the Royal Observatory perched atop the high reaches of Greenwich Park. Look even more closely and you will see the one of the world’s first public time signals fixed to its roof.

The Greenwich time ball has been a London landmark for 180 years, since it was first constructed in 1833. But it is more than just a tourist attraction. Until the early twentieth century it was a life-saving technological tour-de-force which enabled sailors leaving Britain’s busiest port to find Greenwich time to a fraction of a second – not for punctuality but for navigation.

Just over a decade after its erection, the Illustrated London News ran a major feature on this high-tech time-check.

'The keeping of true time is important to all persons', it observed, 'but to those engaged in navigating the "trackless seas", it is of such consequence, that the government … have not hesitated to expend large sums of money for its discovery, preservation, and announcement to the world.'

It is hard, today, to imagine this little cluster of modest brick buildings as a national centre for scientific excellence. But that is what it was.

As the newspaper explained, 'from the beauty of the instruments, the exactitude of the observations, and the high scientific ability of the officers engaged, the once difficult problem of finding the precise instant when one o’clock touches the world’s history, is no longer a matter of doubt or difficulty.'

We’ve developed other ways to know the time since 1833, but the ball still keeps dropping, and if you wait patiently on the riverside at East India with a pair of binoculars, you can still observe the precise instant of one o’clock every day.

Want to know more? Set your calendar for what promises to be a superb AHS London Lecture by Douglas Bateman on 19 September. See the website for details nearer the time.

Happy St Lubbock’s Day

This post was written by David Rooney

If you live in the UK or the Republic of Ireland, I hope you enjoyed the bank holiday earlier this week. Perhaps you went with family or friends to one of the many great museums with horology collections.

For bank holidays we can thank the remarkable Victorian polymath, John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury), who was the subject of a fascinating Royal Society conference I attended recently.

Lubbock is usually associated with the preservation of Britain’s ancient monuments such as Avebury. In 1882 his landmark Ancient Monuments Act was passed. But this was not nostalgia – Lubbock believed the relics of the past helped us understand our own progress, and he was about as modern as you could get in the late nineteenth century.

It was in electricity that Lubbock truly blazed a trail, a story I’ve recently been researching. Many in the AHS are interested in electrical timekeeping, a subject with more than a century and a half of history, and the place of the electrical industries in this story is crucial.

In 1882, the same year that he guided his ancient monuments bill to completion, Lubbock also sponsored the Electric Lighting Bill, and became a director of Thomas Edison’s offshoot company formed to bring electric lighting to Britain. His firm financed and founded the world’s first public electric power station, on Holborn Viaduct, and the following year he steered through the merger of Edison and Swan, Britain’s two pioneering electrical companies.

Lubbock once gave a lecture praising the work of William Cooke, Charles Wheatstone, Alexander Bain and Louis-Francois-Clement Breguet, amongst others. Electricians, yes, but horologists too.

So if, on your bank holiday museum trip, you saw clocks by any of the electrical pioneers, it is worth thinking of the role John Lubbock played in creating the modern electrical world – and in creating a world that values the relics of the past. And you can also thank him for giving you the day off.

Time for everyone

This post was written by David Rooney

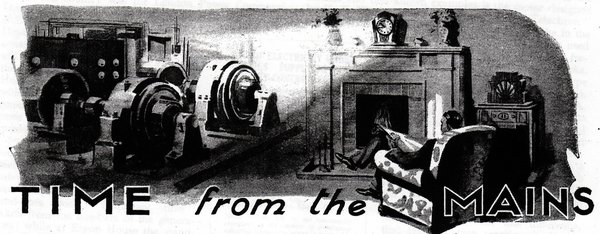

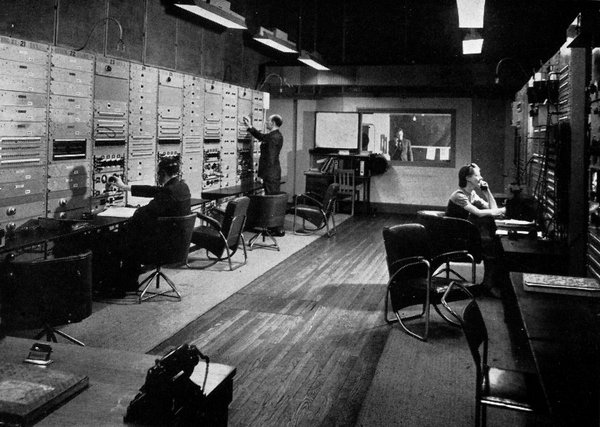

In 1947, the British chronicler of timekeeping, Donald de Carle, wrote the following tribute to American engineer Warren Marrison: ‘it is to him we are indebted for the most accurate timekeeper in the world.’

Marrison worked at the Bell Telephone Laboratories with J.W. Horton. And in 1927 they had made the first quartz clock. It was a game-changer.

The electric clock pioneer Frank Hope-Jones sought to calm fears about the new technology, explaining in 1944 that ‘There is no reason to be afraid of the quartz clock. The trick whereby the vibration of a resonator can be maintained by a vacuum tube – the triode valve of our radio set – is easily learnt.’

He was right. By the end of the Second World War, Britain’s national timekeeping service was based on quartz clocks and today the technology underpins most modern time measurement.

But I think the quartz clock was more than just a new technology. It was one of a series of twentieth-century innovations that represented a new scientific politics, presented publicly as an alternative to nationalism that was ripping the world apart at the time.

If you want to know more, and to contribute to the debate, you might be interested in ‘Time for Everyone’, an international symposium being held at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, on 7 – 9 November this year. I’ll be there speaking about quartz clocks and the public politics of science, but if that’s not to your taste, you’ll also be able to hear other AHS speakers including Chris McKay, Jonathan Betts and James Nye, as well as a host of fabulous presenters from around the world.

All the nation’s oil paintings online

This post was written by David Rooney

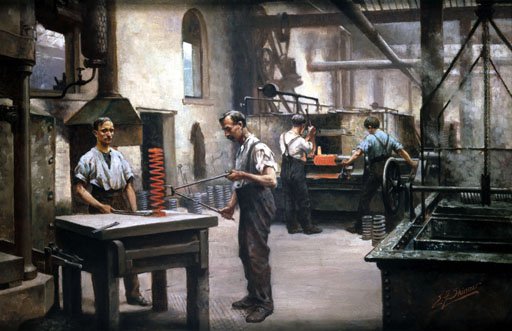

Richard Dunn’s blog post about the Board of Longitude online project reminded me of another exciting digitisation. The ‘Your Paintings' website, run by the BBC in partnership with the Public Catalogue Foundation, aims to show every oil painting held in a UK national collection.

This is a remarkable project. You can see 212,861 paintings online!

I work at the Science Museum, and 297 of our paintings are represented on the site. I picked out three to show you, by Edward Frederick Skinner, depicting file-making and spring-making during the First World War.

OK, they’re not strictly horological, but I think they’re wonderful, and offer a welcome view of women in the engineering workplace too.

This is also an interactive project. You can get involved by tagging the paintings – choosing your own words to describe what can be seen in the images. This will grow to become an important user-generated finding aid.

And so to horology. There are 59 paintings which include the word ‘clock’ in the title. 157 include the word ‘watch’ (though that one’s clearly not such a good search term). ‘Horology’? None, yet, but for ‘antiquarian’ there are three. And there’s one with the word ‘horological’ (the British Horological Institute’s collection is represented).

But that’s titles. Like I said, you can tag paintings yourselves, so if you find a painting which depicts a watch, or a clock, or a fusee-cutting engine or whatever, then tag it – whatever its title – and help others find it in future.

My fellow blog-writers from the British Museum and the National Maritime Museum will doubtless chip in to mention highlights from their own collections. But, really, it’s hard to know where to start! Happy viewing…

Seventy-Seven Clocks

This post was written by David Rooney

One of the security officers where I work stopped me a few weeks ago. He was reading a crime fiction novel and thought I might be interested. It’s called ‘Seventy-Seven Clocks’. You can perhaps see why he thought of me.

During these long January evenings, many of us find time to catch up on our reading – and there’s a lot to catch up on.

I am sure you are already onto your second reading of Bob Miles’s superb masterwork on the Synchronome company, published by the AHS last year. And if you haven’t yet seen a copy of Ian White’s exploration of English clocks for the Eastern markets, the AHS’s latest book, then there’s a treat in store for you.

But having devoured those two books, you might want something a little lighter, and for that, I can recommend Christopher Fowler’s Seventy-Seven Clocks.

With chapter titles such as ‘Horology’, ‘Clockwork’, ‘Automaton’ and ‘Mechanism’, it’s shot through with mechanical ingenuity. (There’s also ‘Vandalism’, ‘Detonation’, ‘Darkness Descending’ and ‘Glorious Sacrifice’, so it’s not for the faint-hearted.)

I don’t want to spoil the plot, but suffice to say anyone who’s a member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, or who collects clocks and watches, or who has ever been involved in running a business might well be absorbed by Fowler’s fictional tale.

It’s beautifully detailed, acutely observed, and full of horology – although I never imagined it could be so wicked ! I’ve since read other titles in Fowler’s series and they’re great. One mentioned the sundial-fountain in St Pancras Gardens by horological philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts that I wrote about a few months ago. Coincidence!

Happy reading, whatever’s on your bedside table, and very best wishes to you all for 2013.

Time on the BBC

This post was written by David Rooney

A couple of weeks ago, BBC radio listeners around the world celebrated the 90th anniversary of the corporation’s founding as the British Broadcasting Company.

On 14 November, a special edition of Simon Mayo’s Drive Time show was broadcast live from the Science Museum, London, in front of the first BBC transmitter, known as ‘2LO’. It’s on show as part of a free temporary exhibit.

Radio broadcasting changed the face of timekeeping. When the BBC was founded in 1922, wireless time signals had been around for about a decade, transmitted from the Eiffel Tower, but they were for specialists, not the public. The BBC brought accurate Greenwich time into the living rooms of the nation.

The first BBC time signals came from the announcers reading out the time. Within a year, a special set of tubular bells was in use, sounding time by the Westminster chimes. But in 1924, the now-familiar ‘six pip’ time signal began. And it’s still in use today – although listeners on digital radio hear the signal a couple of seconds late. Progress, I guess.

But the six pips wasn’t the only time signal set up by the BBC in its earliest years. The familiar sound of Big Ben was also captured live by BBC microphones from 1923 – and that system too is still in place.

It’s time, I’m afraid, for the inevitable plug: to find out more about time signals on the BBC, try my book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady. In it, you can discover why Dame Nellie Melba had reason to say, ‘young man, if you think I am going to climb up there, you are greatly mistaken!’

Happy birthday, BBC…

Time by telephone kiosk

This post was written by David Rooney

A few weeks ago I wrote about telephone kiosks. Today I’m returning to that theme, because I’m fascinated by how many clocks are embedded in our daily lives, hidden in the everyday infrastructure surrounding us.

The nights are drawing in. We’ve reset the clocks back to GMT for another year, and many of us start travelling to and from work in the dark. Thanks goodness for street lights – and for the time switches that turn them on and off every day. Countless clocks hidden inside countless lampposts.

But, every so often, hidden technologies reveal themselves, either by accident or design. In 1931, Britain’s watch and clock makers were told about a new way to find the time when out on the street.

'The latest type of Venner Time Switches installed in the G.P.O. telephone kiosks have a glass window over the dial. The purpose is to enable their timekeeping to be more easily checked, but in addition, the device will be useful to the public, for the time to the nearest five minutes can easily be seen.' The Watch and Clock Maker, 15 November 1931.

These time switches were used to operate the kiosk’s lamp, and they were pretty sophisticated.

Each one was a spring-driven mechanical clock, wound up every eight hours by an electric motor. In case the kiosk’s power supply failed, the time switch had enough power in its spring to operate the clock for three days. And every day the switching times were adjusted to track the rising and setting of the sun.

You can find out more from a 1934 article reproduced here. But could the time switches really be ‘easily’ seen, as the quotation states? Here’s a photograph of one of them in situ. I’ll leave you to decide…

Antiquarian horology in a graveyard

This post was written by David Rooney

Last weekend I went for a walk around King’s Cross and St Pancras, London. The area’s undergoing great change right now as part of a huge regeneration project. I was on the hunt for the mausoleum of one of the world’s greatest antiquarian collectors, Sir John Soane.

One of my most cherished places is the Soane museum in London, presented to the nation in 1833. Soane’s collection there is quite remarkable.

Sarcophagus in the basement? Check. Hogarths and Turners lining the walls? Check. The most exquisite juxtapositions and delightful sight-lines? Check, check, check. It’s a place like nowhere else. Go often!

My particular reason for viewing Soane’s tomb was that it was used by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott as inspiration for his famous red ‘K2’ telephone kiosk. I like things like that.

So far, so antiquarian. But where’s the horology? Well, I was on my way out of St Pancras Gardens, where Soane’s memorial sits, when I encountered a memorial sundial erected in 1879 by Baroness Burdett-Coutts, one of the great Victorian philanthropists and an early supporter of the British Horological Institute.

Isn’t it priceless? The sundial is inscribed, ‘tempus edax rerum’, or, ‘time is the devourer of all things’.

I was struck by the calm atmosphere of the gardens set amidst blocks of housing, the railway lines out of St Pancras, a hospital and the general bustle of London. I think the calmness came in part from the embedded memories in the memorials and inscriptions, which were often moving.

Time is the devourer of things. But we have found ways to use things in order to remember. Periodically, they might be reconfigured, as Soane’s tomb became a telephone kiosk. But that’s just our way of killing time.

A multiplicity of times

This post was written by David Rooney

David Thompson’s post about Metamec ‘time savings’ clocks excited me, because I am interested in the wider cultural meanings around seemingly innocuous phrases such as ‘time is money’.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on the subject for the Science Museum’s ‘Ingenious’ website. It looked at the history of Benjamin Franklin’s 1748 phrase and how its meanings in different times and places varied.

Reading the article back, I have been reminded of a fascinating book by anthropologist Kevin Birth called Any Time is Trinidad Time (University Press of Florida, 1999).

Here’s what I wrote for the Science Museum:

'Trinidad, a Caribbean island between Venezuela and the USA, has a rich history of settlement and immigration. It is ethnically and culturally highly diverse, with residents of mainly Black and Indian origin mixing with Spanish, French and English colonial culture.

'Social anthropologist Kevin Birth spent time living there in 1989 in order to study cultures of timekeeping. Starting out with the often-used phrase "any time is Trinidad time", originally attributed to calypso singer Lord Kitchener, Birth explored the ways people come together with differing notions of timekeeping, and how conflicts are managed.

'He also looked at phrases like "time is money", "time management" and "budgeting time" and found that their use and meaning is highly complex and culture-specific. Generalisations were impossible.

'We all carry around with us a great variety of "personal times" – value systems linking time with activity – and we deploy them in highly complex ways according to culture, context and circumstances. Phrases like the Lord Kitchener lyric are complex devices used to oil the wheels of societies under time pressure.'

If you’re interested in how different societies use clocks, I can heartily recommend reading Birth’s book.

Decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation

This post was written by David Rooney

I spend quite a lot of time thinking about leap seconds. They’re the extra seconds inserted into time at midnight on New Year’s Eve every few years.

Recently they’ve been hitting the news, as a proposal led by some American time scientists to abolish the leap second system has caused a bit of a furore.

OK, here’s the deal. For ever, we’ve measured time by the rotation of the Earth. One rotation equals one day. At least, that was the case until Louis Essen and Jack Parry developed the first practical atomic clock, in 1955 (you can see it at the Science Museum).

This technology, once developed and refined, became a more accurate timekeeper than the spinning Earth, so we moved to atomic clocks to measure time.

But we’re animals, and we’re therefore hard-wired to the temporal patterns of the Earth’s rotation – daylight and darkness, the seasons. So a system was designed to keep the new atomic timescale in step with the Earth.

That’s the leap second, and we’ve been recalibrating the atomic clocks with these occasional one-second corrections since 1972. The resulting timescale is called Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC, and it’s never more than a fraction of a second away from Greenwich Mean Time.

So the proposal by the American scientists to abolish the leap second system and let our civil timescale drift away from GMT has set a lot of people thinking about fundamental issues in the philosophy, technology and metrology of timekeeping.

My point? Recently I read about a colloquium held last October in Pennsylvania exploring the implications of redefining UTC as a purely atomic timescale – decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation.

You can read the papers and discussions here (click Preprints). This is truly fascinating stuff – measured, thoughtful and far-reaching, and the first substantial engagement I have read on the implications of this challenging proposal. Well worth a read if you’ve a spare second.

Don’t forget David Thompson’s lecture next week

This post was written by David Rooney

If you came to the AHS inaugural event at the Royal Astronomical Society in January, you’ll know our new venue in Burlington House makes for a superb evening’s entertainment – and it’s free.

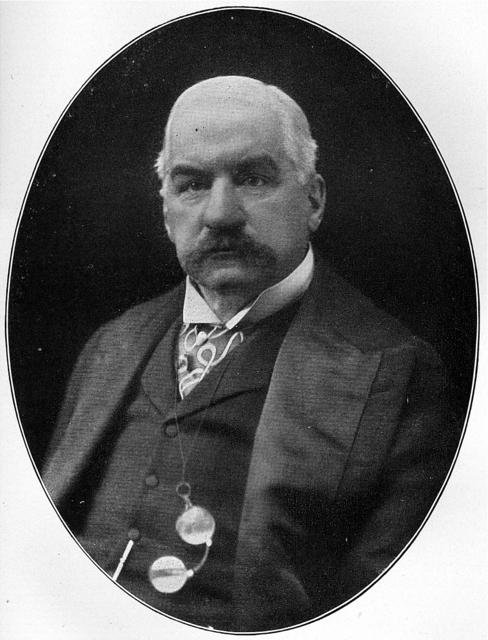

Our second event is next week, so mark it in your diaries now. On Thursday 15 March, AHS Chairman and British Museum curator David Thompson will give the next in our series of talks on ‘The Great Collectors’. This time it’s all about the industrialist, financier and banker, J. P. Morgan.

Whilst Morgan’s business interests are well known, it is his collecting activity that will be in the spotlight on Thursday. Best remembered as a collector of art, gemstones and rare books, he also amassed a considerable number of clocks and watches, concentrating on 16th to 18th century decorative pieces.

This talk promises to provide a sumptuous insight into Morgan’s horological treasures, which David will compare against similar material in other collections. For anybody interested in watches, clocks and the mind of the collector, this will be an evening to remember.

Doors will open at 5.30pm for tea with the talk beginning at 6.15pm. There will be a drinks reception afterwards in the Library. Nearest tube stations are Green Park and Piccadilly Circus.

Thanks to the generous sponsorship of The Clockworks , the event is free – but if you would like to make a contribution to support the work of the AHS further, please do get in touch. We’d love to hear from you.

Time by wireless

This post was written by David Rooney

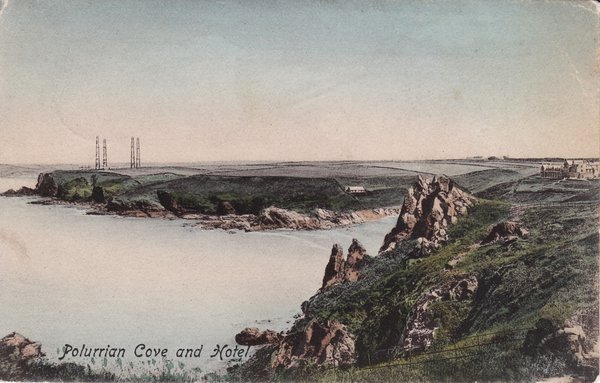

The current header picture at the top of our blog is from an Edwardian postcard entitled ‘Polurrian Cove and Hotel’. Here’s the full version.

I love historic scenes like this which show modern technology set within seemingly timeless surroundings. Here, Marconi’s Poldhu wireless station looms in the background of a picturesque little bay in Cornwall.

This was the transmitter for the world’s first transatlantic radio message, received in Newfoundland, Canada, in December 1901.

One of the earliest uses of wireless communication was radio time signals. Experiments began in America in about 1904, with time signals from Paris’s Eiffel Tower being broadcast from 1909. Soon, standardised international codes were established, giving a much-needed boost to ships and many others who needed accurate time checks around the world.

Today, radio time signals are still very much with us. The BBC’s six-pips signal, inaugurated in 1924, is still accurate to a fraction of a second – as long as you’re listening on analogue. Coded time signals are sent out by the National Physical Laboratory from a transmitter in Cumbria, a system that began in 1927. And even the latest satellite navigation systems operate on super-precise radio time signals.

William Mitchell’s 1923 book, Time & Weather by Wireless, is a terrific read or, if you can’t get hold of a copy, I talk about the history of radio time in my 2008 book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady. And if you want to get more deeply involved, you might consider joining the AHS and its electrical timekeeping group. It’s full of people who think Edwardian postcards of Cornish transmitter masts are cool.

You do think the postcard’s cool, surely. No? It’s just me? Oh.

First AHS event at Burlington House

This post was written by David Rooney

Our 2012 London Lecture Series kicked off in style last week, when over 100 AHS members and friends flocked to the Royal Astronomical Society at Burlington House, Piccadilly, for the inaugural event at our new venue.

This special event saw our usual single bi-monthly lecture replaced by a series of speakers offering reflections on objects and ideas in the story of time.

Sir Arnold Wolfendale, astronomer and AHS president, welcomed the society to the RAS, whilst founder member Michael Hurst surveyed our achievements since 1953. Chairman David Thompson looked forward to the coming year, then introduced a further six speakers, each assessing different aspects of the society’s interests.

Jonathan Betts explored the study of domestic clocks, followed by David Penney considering issues in pocket and wristwatch history. Matthew Read offered a vision of the society’s role in conservation and material research, whilst Keith Scobie-Youngs outlined the challenges and opportunities offered by turret clocks. James Nye gave a sparkling presentation of the electric timekeeping group’s achievements over four decades, and the talks concluded with Andrew King assessing opportunities for future research.

The event proved exceptionally popular, with all tickets allocated well in advance and additional space being provided in the RAS council room, linked by video to the lecture theatre.

The talks were followed by a champagne reception generously sponsored by The Clockworks, a new gallery, conservation workshop, library and meeting space dedicated to electric timekeeping, launching in London later this year.

Our next London lecture will be held on 15 March, when David Thompson continues our series of talks on the great clock and watch collectors. It promises to be an enlightening event – look forward to seeing you there.