The AHS Blog

A new addition to the galleries at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

The extraordinarily accurate ‘Burgess Clock B’ was recently installed in the Royal Observatory’s Time and Longitude Gallery where it will be on display for the next three years.

The following filmed interview introduces the work of Martin Burgess and the project behind this remarkable timekeeper.

First shown at the Harrison Decoded conference, held at the National Maritime Museum in April, 2015.

Further information on Clock B can be found here.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ Time Machine: perpetual calendar or not?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

I am fascinated by gimmicks used by past watch manufacturers to make their products stand out in a crowded marketplace and this post is the first in a short series on some attention seeking watches that have piqued my interest.

This post takes a look the Wittnauer ‘2000’, a quirky automatic wrist watch from the 1970s.

It is a snazzy-looking chunk of a watch and is impressively big at 46mm across the case and crown; the dial does not disappoint with its day, date and complex-looking calendar information around two apertures at twelve and six o’clock.

It was advertised in the early 1970s as a time machine with perpetual calendar, which is technically correct but arguably a little misleading.

The perpetual calendar is a celebrated complication prized by collectors of high-end wrist and pocket watches.

The intricate mechanism required to keep the calendar in step with the short months and leap years demands multiple precisely made components, is only found on the best watches and, unsurprisingly, its presence in a watch hikes the value substantially.

Stephen McDonnell’s recent innovative perpetual calendar design. Uploaded to Youtube by Quill and Pad.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ has a perpetual calendar, which does conform to the same definition.

The date display is a standard type, which must be manually advanced at the end of a short month. It is more normal for the calendar to be set using the crown, but why do that when you can have an extra button on the outside of the case? Instead of keeping the date in sync, it uses tables and a revolving scale to reckon the day of the week for a given date.

The mechanics of the design are very simple, the revolving disc has a contrate gear on its reverse, which is driven by a pinion attached to a second crown.

The years and days of the week are printed on the revolving disc and, as can be seen in the image, aligning the year with the month on the lower table (at six o’clock), places each day of the week above one of seven columns (at twelve o’clock) that contain the relevant days of the month.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ perpetual calendar employed an old and simple technology to allude to luxury. For a modest price it had bags of 70s style and, as with any self-respecting time machine, had buttons aplenty!

Commemorating an invasion that never happened

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

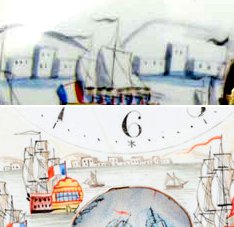

Last month saw the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic era. To mark the anniversary, this week’s blog posting looks at two curious watch dials. The unusual point being that they both appear to come from the same manufacturer, but were made to celebrate victories on both sides of the conflict. One of which never happened.

The first of the two watch dials was made around 1798 when the prospect of a French invasion of England was real and, for many, a terrifying prospect.

Rumours abounded of the French rafts that would carry tens of thousands of troops and weapons to English shores. The images of these vessels distributed by the printmakers ranged from the allegedly factual to the overtly ridiculous.

The French perspective was bullish about the prospect of invasion. Not only were they confident of success, but they also believed that the English would, for the most part, welcome the invasion.

Gillray’s print (above) records that there were indeed those who may have welcomed the French. Whig collaborators are shown on the right-hand-side of the picture trying to winch the French transporter ashore and their efforts are being foiled by Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, seen as the wind blowing the flotilla to destruction.

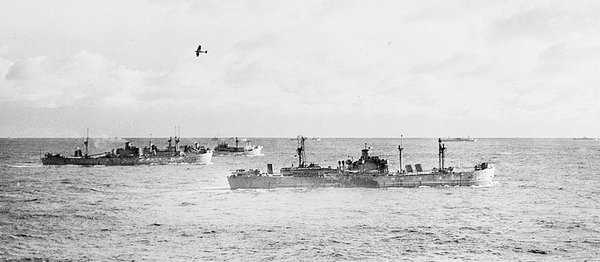

The dial depicts the ‘descente en Angleterre’ with a more traditional fleet of ships sailing towards the heavily defended English shoreline and serves as a useful glimpse into the mind of the manufacturer, keen to capitalize on the bullish French mood of early 1798.

The scene on the second dial is identifiable as the Battle of the Nile because of the burning ship on the left-hand-side of the image. This represents the French Flagship, L’Orient, which exploded with such violence that fighting was temporarily halted and it became a symbolic feature in popular representations of the Battle.

There is a near-identical row of box-shaped buildings placed along the horizon on both dials. This suggests that they both came from the same source. Such buildings seem more appropriate for the northern coast of Africa than the southern shores of Britain and so it was probably a generic depiction preferred by the artist.

As an asides, the invasion watch dial has a later counterpart in the Museum’s medal collection. A rare sample medal was struck in 1804 with dies intended to be used in London by the victorious French conquerors. Despite amassing a substantial force in the Boulogne area, the embarkation was prevented, principally by the diversion of troops and resources to the Battle of Ulm and, secondarily, by the English blockades.

Harrison decoded: towards a perfect pendulum clock

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In July 2014 the NMM hosted on one-day conference, entitled Decoding Harrison, which presented the story of around forty years of collaborative research into John Harrison’s complex and surprising pendulum clock theory.

During the conference the exciting result of a previously unannounced and unofficial test of Martin Burgess’s ‘Clock B’ at the Royal Observatory was revealed.

‘Clock B’ is one of two clocks made from modern materials, chiefly duraluminium and invar, that follow the perceived format laid out in Harrison’s convoluted text: Concerning such mechanism… the lengthy title gives the reader an accurate sense of the complexity of the book itself.

For example, footnotes occasionally run across more than one page and if that was not enough, some even have their own footnotes. In short, it is not an easy read.

The unofficial test was conducted with the clock sealed into a Perspex case, which was made tamper-proof by applying two wax impressions, kindly provided by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers and the National Physical Laboratory on 1 April, 2014, over wires threaded through the nuts and bolts that hold it shut.

On 6 January, 2015 – some 280 days after the case was sealed – Museum staff and the Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, Jonathan Betts, gathered to witness the going of the clock and initiate an official 100-day trial of its timekeeping.

Using the a radio-controlled clock that receives the MSF time signal, the accuracy of the speaking clock was confirmed and then used to determine to going of ‘Clock B’. We determined that the clock was showing UTC -1/4 second.

The clock will be observed throughout the trial using the above method as well as being continually monitored by a Microset and GPS as well as the environmental conditions inside the case (temperature, humidity and barometric pressure).

The trial is intended to prove that this clock is the most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free-air in existence. Throughout the trial I will be blogging and posting updated videos to youtube, which you can subscribe to.

To wrap up this exciting experiment we will be presenting the data collected, the current understanding of how the clock works and, indeed, why it works so well in a one-day conference at the National Maritime Museum on 18 April, 2015, which incidentally will mark the 3 year anniversary of Clock B’s stay here in Greenwich.

Details of the programme will be announced shortly.

A second in one-hundred days: insanity or genius?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In 1775 John Harrison made a critical remark about Graham’s dead beat escapement, saying, of George Graham, that '…either he must be out of his Senses, or I must be so!'

Later in the same publication he stated of his own clock that '…there must be then more reason…that it shall perform to a second in 100 days…than that Mr Graham’s should perform to a second in 1.'

Keeping time consistently to within one second in 100 days was a degree of accuracy not achieved until around a century and a half later by mechanical clocks such as Shortt’s free pendulum system.

Harrison published his remarks in a vitriolic and virtually impenetrable book, the manuscript and transcriptions of which are freely accessible online.

On reading the book, which contains scattered descriptions of his method, the celebrated watchmaker Thomas Mudge, stated of Harrison that the book’s contents had '…lessened him very much in my esteem…' and that '…there are several things which he says about Mr Graham’s pallets and pendulum that are absolutely false…'.

The London Review of English and Foreign Literature described the work as 'one of the most unaccountable productions we ever met with' and went on to say that 'every page of this performance bears marks of incoherence and absurdity, little short of the symptoms of insanity'.

Harrison’s words were not taken seriously by any of his contemporaries and his radical statement about the capabilities of his pendulum clock, with its large pendulum arc, relatively light bob, and recoil grasshopper escapement, remained largely unexplored until the 20th century.

Then, in 1977, a number of horological scholars, who became known as The Harrison Research Group, began to look at his theories afresh.

Martin Burgess’ Clock B is a product of this collaborative research and represents one of the most significant historio-technical investigations in recent years. Recently, numerous experiments have been tried on the clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with exciting results.

To learn more about this intriguing project please join us for a special one-day conference on July 12 2014 at the NMM.

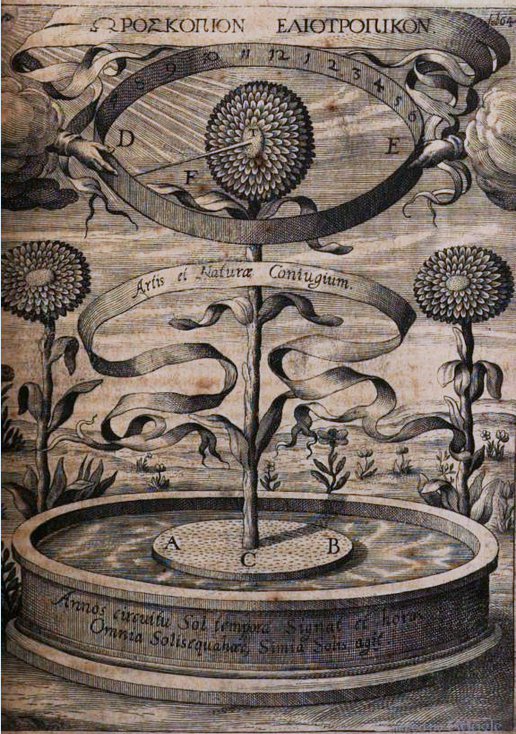

An experiment in ‘florology’

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

Recently, I have been looking at the role of timekeepers in the history of science and whilst reading around the pre-pendulum era, happened upon a blog-worthy experiment conducted by Athanasius Kircher (1601/2-80).

Kircher, a German Jesuit polymath, applied the then known phenomenon of heliotropism as a method of timekeeping.

He thought that the daily motion of sunflowers as they followed the Sun was caused by magnetic influence and thus inferred that they could be usefully used as a clock. As can be seen in his magnificent illustration, Kircher planted the sunflower in a cork pot and floated it on water, providing a frictionless pivot, and inserted a pointer through the flower to indicate time against the annular chapter.

Kircher noted that his clock was disturbed by the slightest of breezes and, when kept away from sunlight, it withered and its motion slowed. This, however, did not end the experiment. He tells us that he had the good fortune of meeting an Arab trader who happened to have amongst his aromatic wares a substance with similar horological properties to the sunflower.

The deal was struck and Kircher parted with his sundial signet ring for the horological stuff.

It has to be said that this episode is possibly a theatrical device to colour the account and introduce the use of sunflower seeds and root instead of the plant itself, but worth repeating – even if it’s just an excuse to show a beautiful horizontal sundial ring!

Today, we know that this diurnal motion is caused by sunlight and so Kircher’s clock could never have worked in the way intended, but one cannot help admire his ingenuity in applying a mystery of the physical world to tell the time. M. Becker’s 2011 time lapse movie shows that it is possible to use a flower as a twenty-four hour clock, but only in summertime at a latitude close to the north or south pole.

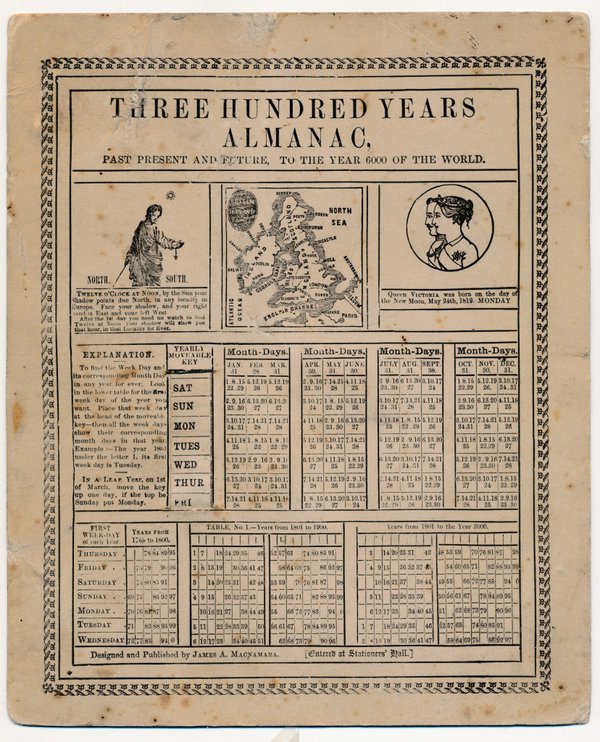

300 years

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

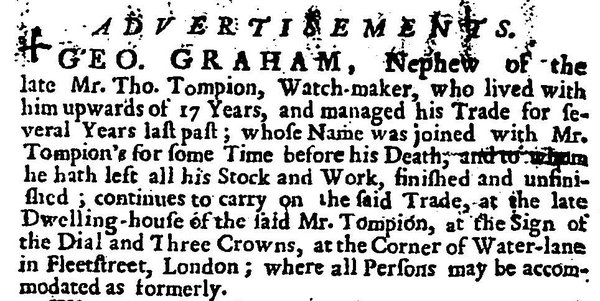

This year saw the tercentenary of the death Thomas Tompion (b.1639), the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’ and his life is celebrated in two special exhibitions: the first at the British Museum, entitled ‘Perfect Timing’, which focuses on the magnificent Mostyn Tompion and the second, ‘Majestic Time’, at the National Watch and Clock Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Tompion enthusiasts should be further delighted by the announcement of the forthcoming publication of ‘Thomas Tompion, 300 years’. The book promises a wealth of new detail, fresh illustrations and includes Jeremy Evans’s previously unpublished chronology of Tompion’s life.

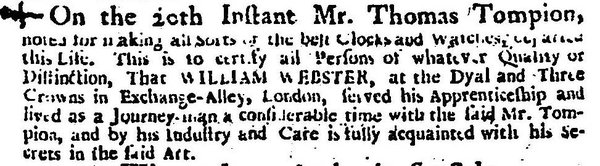

This tercentenary marks not only an end, but a new beginning as Tompion’s nephew by marriage and then business partner, George Graham (c.1673-1751), inherited and continued the business at the corner of Water Lane. As far as I am aware, the earliest announcement of Graham’s succession was first advertised in The Englishman one week after the death .

William Webster, however, did not show the same reserve. He had an advert published the day after Tompion’s death in two papers: The Mercator or Commerce Retrieved and The Englishman. His announcement of the death was a thinly veiled attempt to attract business and was repeated in various papers that week.

Unlike Webster, Graham was not apprenticed to Tompion (several publications incorrectly cite Graham as being so). He joined the household sometime around 1676 after gaining his freedom from apprenticeship to Henry Aske.

Evidence suggests that Graham did not serve his entire apprenticeship under Aske and it is currently a mystery as to where he was during the last years of his apprenticeship.

Looking forward to next year there is another important tercentenary, that of the Queen Anne Longitude Act. George Graham played an important role as an encourager and advisor to both Henry Sully and John Harrison in their efforts to produce sea-going clocks and will feature in a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum next year.

Falling back

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

It’s that time of year again when our faithful timekeepers quiver, for fear that we will ignore the advice of the clockmaker and attempt to turn the hands backwards, as we return to daily life punctuated by GMT (or UTC if you prefer) on Sunday.

I think it is fair to say that the majority of us are more sympathetic towards the autumnal adjustment, as we can luxuriate in the hour that was ‘banked’ in the spring, so perhaps now is the ideal time to bring this discussion to the AHS blog.

Today, internet searchers will find that the energetic equestrian builder from Petts Wood, William Willett has been eclipsed as the architect of Daylight Saving Time (DST) by George Vernon Hudson, the English born New Zealand entomologist, who first proposed his scheme to the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1895.

In England, thanks to Willett’s monumental efforts, the Daylight Saving Bill was presented before parliament in 1908 and it offered that ‘for a period of 154 days, an increase of sixty minutes more sunshine in the evening of each day’.

The then President of the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill astutely noted in the margins of his copy that this was an ‘optimistic view of our climate!’

Despite Churchill’s support the Bill did not pass and it was eight years before Daylight Saving was introduced as a wartime economy pre-empted by its earlier implementation in Germany.

This Sunday, as you pause the pendulum on your antique clock, will you follow Winston Churchill’s lead and ‘raise a silent toast to William Willett’ and perhaps reflect on the 154 hours of extra ‘sunshine’ that you enjoyed this year?

Home time

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

As next year’s AHS conference will be shaped by the theme ‘Military Time’, it seems appropriate that this post should follow the military theme and by chance, as with David Read’s recent post, it includes a radio.

There are two HS.4 navigational watches in the National Maritime Museum collection, both retailed by the firm H. Golay and Sons, which were used by the Fleet Air Arm in Fairey Swordfish aircraft during WWII.

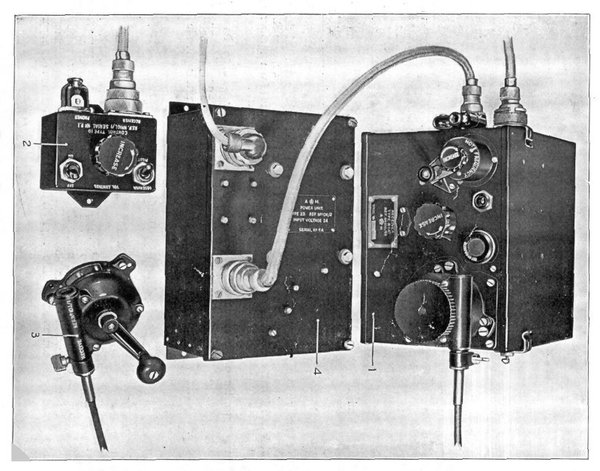

We learn from the 1941/1942 Admiralty Manual of Navigation that these watches were known as beacon watches and that they were only to be used in aircraft fitted with an R1147 radio receiver.

The carriers were equipped with a revolving beacon that continuously transmitted second pulses, making a full rotation once per minute. The crucial feature of this system was that the beacon emitted a different sounding signal when it was pointing due north. Prior to launch (these planes were catapulted into the air) the observer would tune the radio receiver to the beacon and set the bezel of the watch so that zero on the outer scale and the tip of the second hand align precisely at the time of the northern signal.

When returning to the carrier, the observer on board the aircraft would turn on the radio and listen to the beacon’s signal. The strongest reception would be experienced when the beacon was pointing directly at the aircraft and using the watch, the aircraft’s position relative to its carrier could be found and the pilot given the course to take.

If we take the watch shown above, for example, as indicating the moment of the signal’s maximum intensity, the aircraft’s position would be approximately SSW of the carrier. The primary benefit was that these slow aircraft could home in on their carrier from up to 100 miles away without sending out radio signals that may betray their position to the enemy.

This ingenious horological adaptation helped to save lives and is just one example of innovation necessitated by war that could be explored at next year’s conference.

If you feel that you can contribute a talk that would fit ‘Military Time’ theme, you are invited to contact the AGM lecture coordinator, Rory McEvoy, Curator of Horology, Royal Observatory Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SE10 9NF, e-mail: RmcEvoy@rmg.co.uk. Papers could explore technical horological development as well the wider implications for both civil and military timekeeping. Please note that the theme is not limited to the First World War, and that the military of course includes the ground, sea and air forces.