The AHS Blog

Dreaming of a clock in the slums of Paris

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every clock that left the workshop or factory on its way to a buyer has, we may assume, been coveted by and, we may hope, given satisfaction to its owner. But most of this goes unrecorded, and where traditional non-fiction sources are silent, we may find some glimpses in fiction.

For vivid descriptions of the life of the workers in nineteenth-century France one can do worse than turn to the wonderfully naturalistic novels of Emile Zola (1840-1902).

The book that shot him to fame in 1877 was L’Assommoir; below I quote from the most recent English translation: The Drinking Den , Penguin Classics 2000 rev. 2003, translator Robin Buss.

The novel depicts in graphic style the rise and fall of Gervaise Macquart, who worked as a laundress in Paris during the period 1850 to 1870. There are scenes of abject poverty and alcohol is a key character in the story; but there are also comical scenes and uplifting passages. It is a masterpiece. As one author has put it:

‘L’Assommoir is set in the dirt and filth of working class Paris, where life was hard and lives depressingly short. He researched in great detail the impoverished quarter of which he wrote, so that the work is an ethnographic novel and probably the first of its kind’.

In the poor household of the young Gervaise, a chest of drawers takes pride of place:

‘One of her dreams, which she did not dare mention to anyone, was to have a clock to put on it, right in the middle of the marble top – the effect would be quite splendid. Had it not been for the baby that was on the way, she might have risked buying her clock, but as it was she put if off until later, with a sigh.’ (p. 97).

Three years go by before she is able to act on her desire:

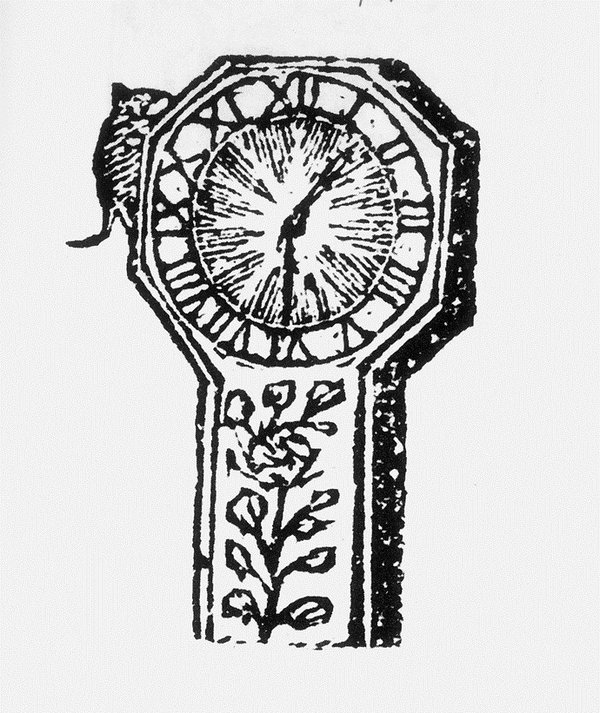

‘She had bought herself a clock; and even then this timepiece, a rosewood clock with twisted columns and a copper gilt pendulum, had to be paid off over a year, at the rate of five francs every Monday. She got cross when Coupeau [her husband] said he would wind it up, because only she was allowed to take off the glass globe and religiously wipe the columns, as though the marble top of her chest of drawers had been transformed into a chapel. Under the glass cover, behind the clock, she hid the savings book. And often, when she was dreaming about her shop, she would sit there, miles away, in front of the dial, staring at the turning hands, for all the world as if she was waiting for some particular, solemn moment before she made up her mind.’ (p. 108).

The ‘dreaming about her shop’ refers to her ambition to make herself independent and set up her own laundry, which indeed she eventually manages to do. Life looks good, she even entertains a large group to a celebratory dinner in the laundry shop.

But it was not to last, and as her life goes in a downward spiral, Gervaise is forced to bring one possession after another to the pawnbroker. She puts a brave face on it:

‘Only one thing broke her heart and that was putting her clock in pawn, to pay a twenty-franc bill when the bailiff came with a summons. Up to then, she had sworn she would starve rather than part with her clock. When Mother Coupeau [her mother in law] took it away in a little hat box, she slumped into a chair, her arms dangling, tears in her eyes, as though her whole fortune had been taken away’. (p. 279).

There is more horology in this novel. She also has a cuckoo clock, which would have been a much less valuable object, but it is never described in detail. Neither is the watch which only once makes an appearance, on the day that she is forced to put it in pawn as well:

‘The little knick-knacks had faded away, starting with the ticker, a twelve-franc watch, and the family photographs.’ (p. 384).

There is also a watchmaker who plays a small role in the story. In the courtyard of the tenement house where she lives are various workshops and shops, including – for a while – her own laundry shop:

‘At the bottom of a hole, no larger than a cupboard, between a scrap-iron merchant and a chip shop, there was a watchmaker, a decent-looking gentleman in a frock-coat, who was continually probing watches with tiny tools, at a bench where delicate things slept under glass covers while, behind him, the pendulums of two or three dozen tiny cuckoo clocks were swinging at once, in the dark squalor of the street, in time to the rhythmical hammering from the farrier’s yard’ (p. 134).

Literary critics may argue that in fiction, clocks and watches are often introduced as symbols, and that therefore novels do not necessarily give a realistic image of the ownership of clocks and watches.

Be that as it may, the story of the struggling laundress Gervaise Macquart, who dreamed of owning an ornamental clock and managed to bring one into her poor home, only to have to part with it again, feels very real indeed.

A clock to remember the Zeppelin raids over London

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

A recent article published in Antiquarian Horology, entitled ‘A Time to Remember’, focuses on a pocket watch in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich that had been recovered from the Titanic, which sank in 1912 after hitting an iceberg.

The hands indicate 3.07, presumably marking the moment the watch entered the water.

The article discusses this and other watches recovered from the Titanic and can be read here.

I was reminded of this when recently I noted a board outside a tavern in the London district of Holborn, drawing attention to a somewhat macabre relic. The pub had been destroyed by a Zeppelin bomb in 1915, and a clock found in the wreckage, marking the time the bomb had struck, could be seen inside the pub.

Step inside, and there it is on the wall. Next to it hangs a clock that is in better shape but lacks its movement. In a show of solidarity, both clocks stand still forever.

The clock is mentioned in a list of ‘London’s top 10 timepieces – Time Out counts down our city‘s finest timepieces’, with this comment:

'When this snug corner-boozer was leveled by a Zeppelin bomb in 1915, one of the few things to be pulled intact from the rubble was the clock that today hangs to the left of the bar, hands frozen at the hour of doom. Locals say the clock can sometimes be heard to whistle, as though imitating the falling bomb. Bollocks, says the barman.'

Two-timing

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The dictionary defines ‘two-timing’ as ‘to be unfaithful to a spouse or lover’ or ‘to deceive, to double-cross’. But that’s not what I want to talk about. What I have in mind here is people who put the clock forward even though they know it’s not the ‘real’ time. Perhaps we can regard this as another kind of cheating.

Some months ago I came across the term ‘Sandringham time’. British Summer Time – putting the clocks forward one hour in April and back again in October – was introduced in 1916, and among those supporting the idea had been King Edward VII (1901-1910).

Here (with thanks to David Rooney who supplied me with a scan of the relevant page) is what David Prerau wrote in his book Saving the Daylight: Why We Put the Clocks Forward (page 12):

'The king had recognized the waste of morning daylight and had already taken royal action: for several years, in order to have more time for hunting, he had been creating his own small sphere of daylight saving time at his palace at Sandringham, and in later years at Windsor and Balmoral castles, by having all the clocks advanced thirty minutes. (The tradition of ‘Sandringham time’ lasted until Edward VIII abandoned the practice in 1936).'

I was reminded of this when this week I finally got around to reading Flora Thompson, Lark Rise to Candleford , a semi-autobiographical series of three books giving scenes from a childhood in rural Oxfordshire in the 1880s and 1890s.

The books were originally published in 1939, 1941 and 1943, and then as a trilogy from 1945 onwards. I quote from the Penguin Modern Classics edition of 2008.

At the age of 14, the main character Laura (Flora) starts work as assistant in a Post Office. It is run by a woman, Dorcas Lane, alongside a blacksmith’s workshop which she had inherited from her father.

'The grandfather’s clock was kept exactly half an hour fast, as it had always been, and by its time, the household rose at six, breakfasted at seven and dined at noon; while mails were despatched and telegrams timed by the new Post Office clock, which showed correct Greenwich time, received by wire at ten o’clock every morning' (page 364).

The Post Office is re-introduced at the beginning of Part 3:

'As she followed her new employer through the little office and out to the big front living kitchen, the hands of the grandfather’s clock pointed to a quarter to four. It was really only a quarter past three and the Post Office clock gave that time exactly, but the house clocks were purposely kept half an hour fast and meals and other domestic matters were timed by them.

'To keep thus ahead of time was an old custom in many country families which was probably instituted to ensure the early rising of man and maid in the days when five or even four o’clock was not thought an unreasonably early hour at which to begin the day’s work.

'The smiths still began work at six and Zillah, the maid, was downstairs before seven, by which time Miss Lane and, later, Laura, was also up and sorting the mail' (pp 395-6).

In the first volume, when Laura is still a small child living with her family in a nearby hamlet, we find another interesting example of dual timekeeping.

One person in the hamlet, ‘Old Sally’, owned 'a grandfather’s clock that not only told the time, but the day of the week as well. It had even once told the changes of the moon; but the works belonging to that part had stopped and only the fat, full face, painted with eyes, nose and mouth, looked out from the square where the four quarters should have rotated.

'The clock portion kept such good time that half the hamlet set its own clocks by it. The other half preferred to follow the hooter at the brewery in the market town, which could be heard when the wind was in the right quarter. So there were two times in the hamlet and people would say when asking the hour: "Is that hooter time, or Old Sally’s?"' (p. 77)

‘A clock which has gone by itself for 2 years’

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In the State Library of New South Wales is a manuscript journal of a trip to Holland undertaken in 1773 by the naturalist Joseph Banks (1743-1820), who from 1778 until his death was to be the President of the Royal Society. His journal can be read on-line here.

Most of his journal, as expected, is related to natural history, but in Amsterdam he visited an unnamed clockmaker who showed him ‘a clock which has gone by itself for 2 years’.

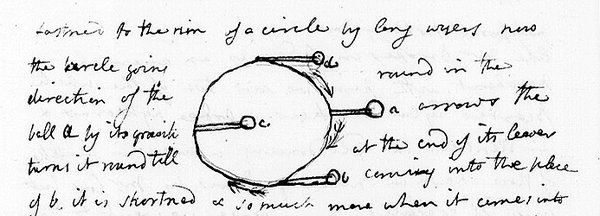

From his description, complete with a sketch, it is clear that he struggled to make sense of what he had seen:

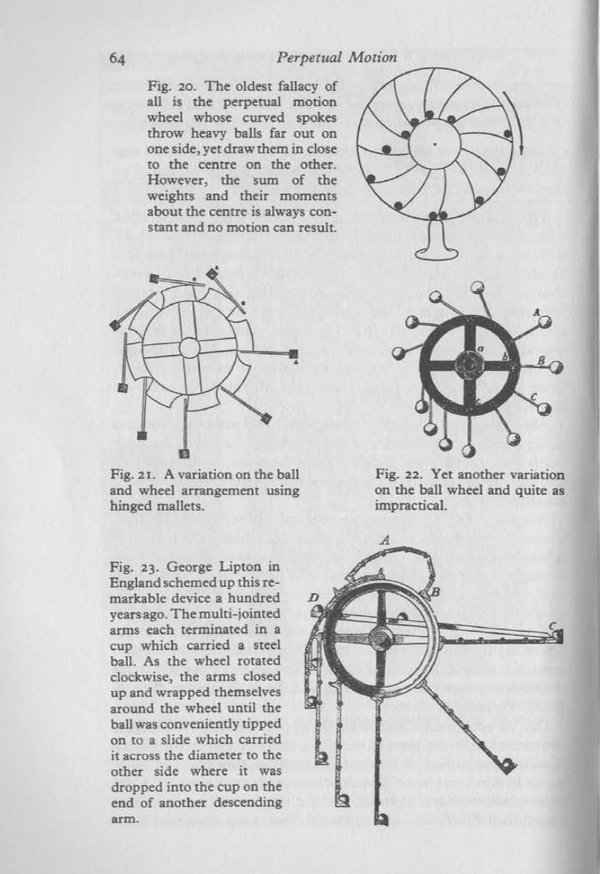

'From hence we went to a clockmaker Mr [name not entered] who has invented a clock which has gone by itself for 2 years & is therefore called not injustly a perpetual motion whether the principle was fallacious I could not discover but it was or appeared to be 4 balls / fastened to the rim of a circle by long wyers [wires] the circle going round in the direction of the arrows the ball a by its gravity turns it round till at the end of its leaver [??] coming into the place of b it is shortened and so much more when it comes into the place of c the balls c & d at the same time becoming longer & in their turns forcing it round whether however a [illegible word] wheel made upon this construction would ever go once round I very much doubt if not there must either be fallacy or some method of applying the principle which I did not understand which is likely as the machine was rather complicated' (pages 51 and 52 – CY 3011/73 and 74).

The concept of perpetual motion, and the idea that one can make a machine that can do work indefinitely without an energy source, has been exercising many minds over the centuries, but the development of modern theories of thermodynamics has shown that they are impossible.

In his book Perpetual Motion: the History of an Obsession, Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume has illustrated several devices that look rather similar to the clock that Banks had seen. We must conclude that the unnamed Amsterdam clockmaker was one in a long line of deluded ‘inventors’.

Night watchmen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Richard Wagner set his glorious opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-singers of Nuremberg) in that German city in the sixteenth century.

In the second act a night watchman sings (the English translation in the vocal score is somewhat awkward as it aims to preserve both metre and rhyme):

'Hark to what I say, good people;

strikes ten from every steeple;

put out your fire and eke your light,

that none may take harm this night.

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat zehn geschlagen;

bewahrt das Feuer und auch das Licht,

dass Niemand Schad‘ geschicht.

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

The act concludes with his re-appearance:

'Hark to what I say, good people;

eleven strikes from each steeple;

defend you from spectre and sprite;

let no power ill your souls of fright!

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat elfe geschlagen;

bewahrt euch vor Gespenster und spuck,

dass kein böser Geist eu’r Seel‘ beruck‘!

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

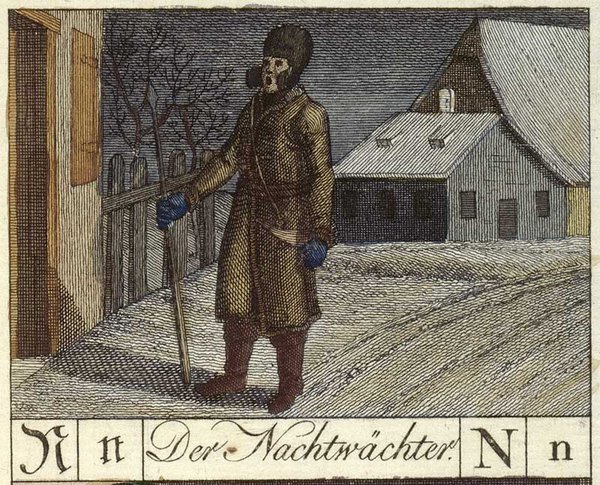

From the middle ages until late into the nineteenth century, the night watchman patrolling the streets at night, calling the time and keeping an eye out for any kind of mischief or irregularities, were a common figure in many towns and cities.

Although he set his opera in the sixteenth century, watchmen were probably still active in Nuremberg when Wagner wrote his opera in the 1860s.

One century earlier, an Englishman visiting Nuremberg recorded in his travel journal 'Every evening about nine o’clock a fellow goes up and down the streets singing, and gives notice of the time of night, and bids people put out their candles. About the same time and at three in the morning trumpets are sounded.' (Sir Philip Skippon, An Account of a Journey Made Thro’ Part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and France , 1752).

In her book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London , Judith Flanders writes that for a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock, stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time.

The patrols of the night watchmen were not an undivided pleasure.

In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Tobias Smollett has a long-suffering character say, 'I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants.'

Acknowledgment. It was Wagner’s opera that made me want to know more about these night watch men, and I found much information in this article: Philip McCouat, ‘Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night’, Journal of Art in Society (2014), www.artinsociety.com.

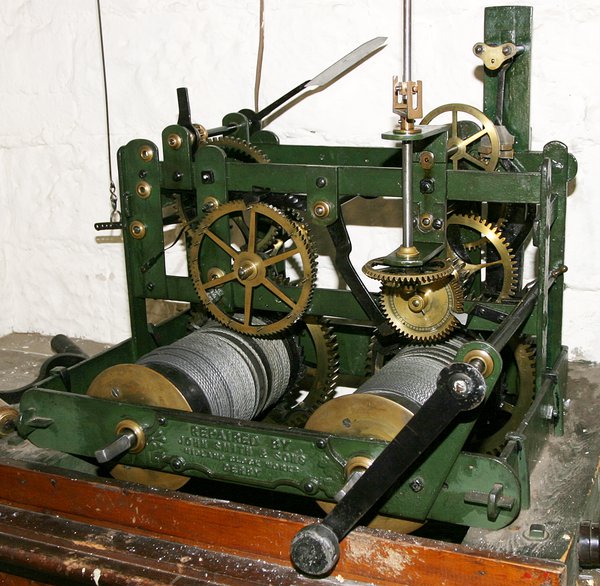

Winding the Caledonian Park turret clock

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

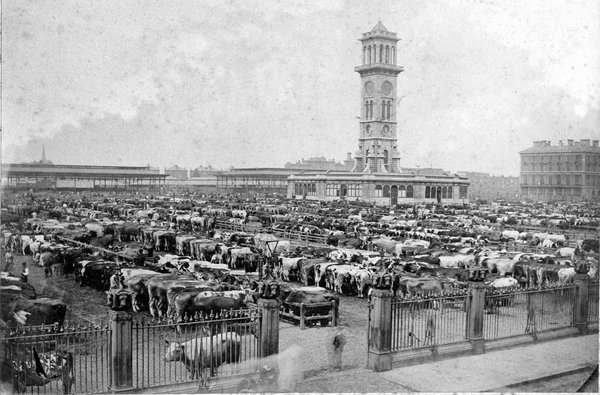

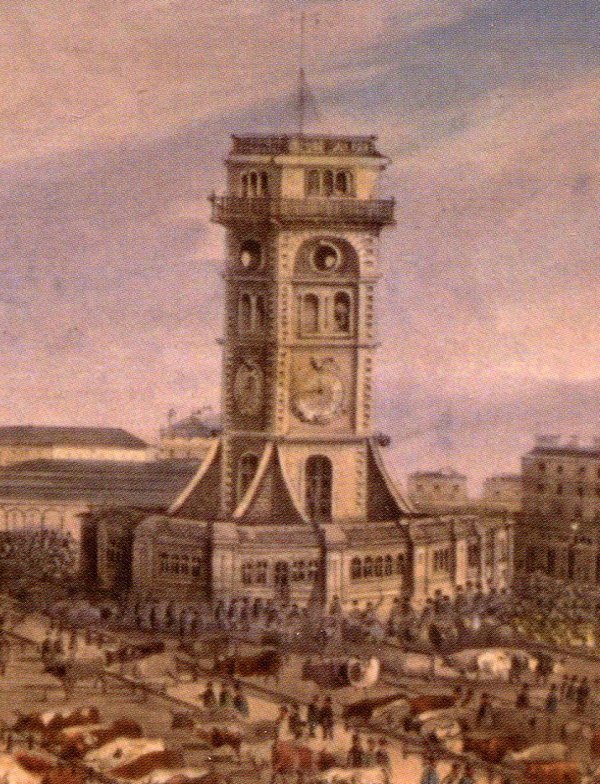

In Caledonian Park, in the London Borough of Islington, stands a distinctive 45 meter clock tower with four dials that can be seen from far away.

It was erected in the 1850s to serve as the command centre of the newly laid out Metropolitan Cattle Market, which had been created to replace the old more centrally located Smithfield Market. The tower is a Grade II listed building.

You can see the clock movement in this short videoclip:

Turret clock expert Chris McKay has recently published a facsimile reproduction of A List of Church, Turret and Musical Clocks. Manufactured by John Moore & Sons. 38 & 39, Clerkenwell Close, London, dated 1877.

For the year 1854 we find: ‘Islington, London Four 10-ft. 6-in. dials, chiming, for the Cattle Market.’

The chimes are no longer in operation, from what I understand at the insistence of nearby residents. But the clock is still running and showing the correct time.

During an open day last summer I had a chance to get into the tower, and to see the clock and enjoy the view from the balcony.

The organizers were looking to extend their group of volunteers for the weekly winding of the clock. I signed up and am on the rota now, so I regularly climb first a cast iron spiral staircase and then a series of steep ladders to get to the movement and pull up the heavy weight.

It’s a good physical exercise and a welcome hands-on experience for someone whose involvement with horology is normally limited to sitting at a desk putting together the quarterly journal of the AHS.

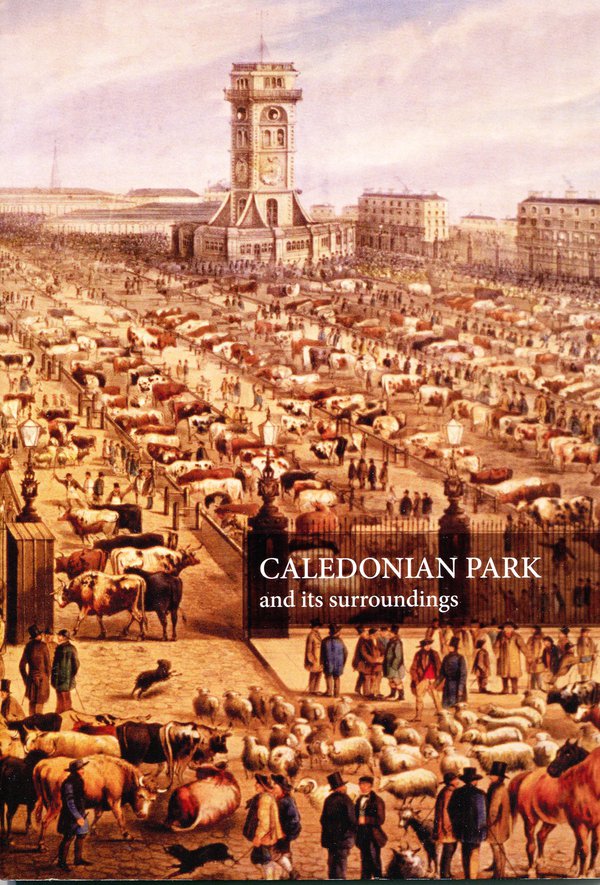

The Caledonian Park Friends Group have published a booklet with much information on the history of the market, which for a while also functioned as a flea market.

The cover shows the market in full swing, but the artist has made a bad job of representing the tower. If the dials were really as low as where he painted them, climbing up to wind the clock would be a lot easier!

Chronometers in hell

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In my previous post, ‘Having a smashing time’, we saw how watches are being tested for shock resistance, which can involve some pretty heavy handling.

Another method of testing timepieces is prolonged exposure to heat and cold. This was especially important for marine chronometers, who would travel to all parts of the globe, so it was important to determine to what degree their rate was affected by temperature fluctuations.

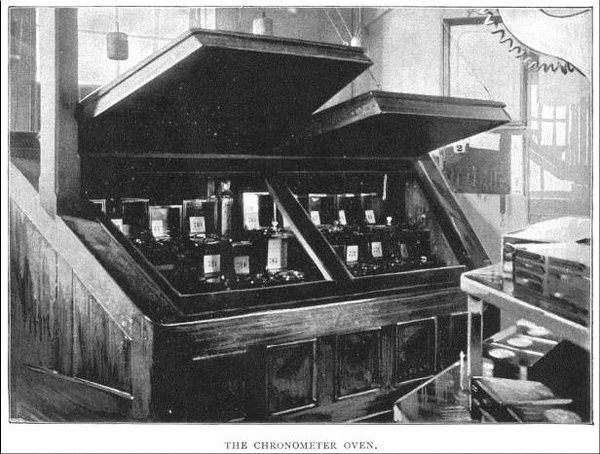

The Time Department at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where the rate of chronometers was tested, had a large oven in which chronometers were kept for eight weeks at a temperature of about 85 or 90 degrees Fahrenheit, that is around 30 degrees Celsius.

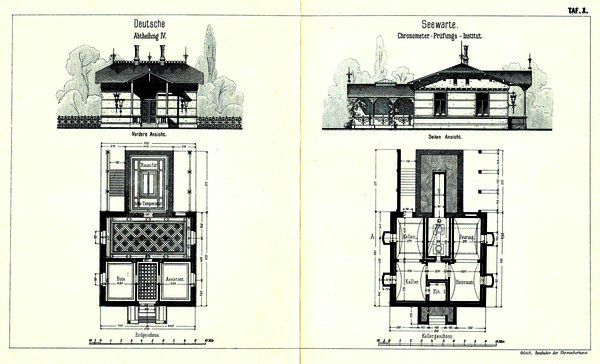

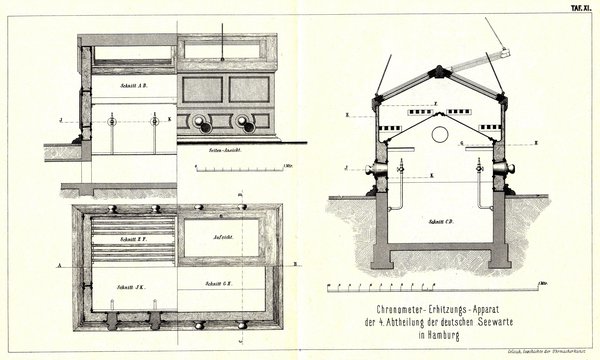

A recent article in Antiquarian Horology had a section on chronometer testing facilities in 19th-century Germany.

In Hamburg they had both an ice cellar and a gas-heated oven. The naval observatory in Wilhelmshaven was less well equipped:

'Neither an ice cellar nor a heating apparatus was available. The radiators of the central heating acted as makeshift for the latter, and tests in lower temperatures were conducted in winter by opening the windows. Sometimes the required temperature of 5º could not be reached due to mild weather'.

Manufacturers of chronometers could have their own heat and cold testing apparatus.

An oven and an ice-box used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons are in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. Normally these two objects are kept in storage, but some years ago they were taken out for display in a temporary exhibition ‘Time Machines’.

When I visited the exhibition, the curator, Dr Stephen Johnston, told me that at first sight some visitors thought the ice box was a toilet!

Sir George Airy, the late Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, in one of his popular lectures drew a humorous comparison between the unhappy chronometers, thus doomed to trial, now in heat and now in frost, and the lost spirits whom Dante describes as alternately plunged in flame and ice.

He was referring to Dante’s La Divina Comedia, Book One: Hell, III, 76-82:

'There, steering toward us in an ancient ferry came an old man with a white bush of hair, bellowing: “Woe to you depraved souls! Bury here and forever all hope of Paradise: I come to lead you to the other shore, into eternal dark, into fire and ice.”'

Having a smashing time

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

On my twelfth birthday I was given my first watch.

I remember that it had the word ‘shockproof’ stamped on the back and that I wondered just how ‘shockproof’ it was. Mercifully I did not try to determine the limits of what it could take.

On Wikipedia I find that ‘shockproof’ should be understood as ‘shock resistant’, and that there is an international standard which specifies the minimum requirements and describes the corresponding method of test.

It is based on the simulation of the shock received by a watch on falling accidentally from a height of 1m on to a horizontal hardwood surface.

In the test the shock is usually delivered by a hard plastic hammer mounted as a pendulum. Some manufacturers are more ambitious.

Under the heading ‘Having a smashing time: Making sure your watch stands the test of time’ a newspaper article describes and illustrates the many types of torture to which the Swiss factory of IWC (International Watch Company) subjects its timepieces.

The impact test is illustrated here with images from the article. A metal pivot, weighted with a 10kg block, is pulled upright, then swings round to hit a watch held in a vice. A cotton sheet is laid out to catch the watch, and technicians check after each impact to see that it’s still ticking perfectly.

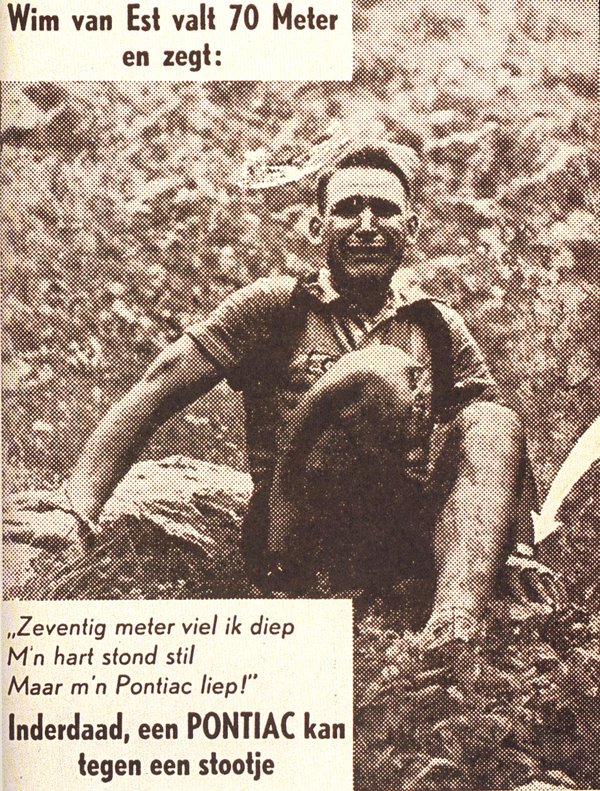

A less carefully planned demonstration of the shock resistance of a watch was given during the 1951 Tour de France, the annual cycle race.

The watch manufacturer Pontiac had sponsored the Dutch team by supplying them with wristwatches. One runner fell and dropped seventy meters down the side of the mountain.

Amazingly, he was not seriously injured. Even better for the sponsor, his watch was still ticking. Pontiac made a successful publicity campaign out of it.

Unreliable public clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

You only have to walk around in your own town to observe that of all the public clocks you pass by, only a few tell the correct time. Many show just any time, others have stopped working altogether.

Last year, a tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Guardian suggested that it was ‘time for a public clock tsar, with power to demand that owners restore their timepieces to reliable service’.

Here I learned of the existence of the blogspot Stoppedclocks, which invites us to ‘help find and fix all the stopped public clocks in Britain’. So if you have a particular gripe about a faulty clock in your area, you now know where to turn to.

There is, of course, nothing new under the sun. More than three centuries ago a correspondent to a London newspaper ventilated his gripe about the unreliability of public time-pieces.

It is quoted here, with the numbers referring to the map, as published in an article by Anthony Turner entitled ‘From sun and water to weights: public time devices from late Antiquity to the mid-seventeenth century’, published in Antiquarian Horology in March 2014.

![Details from John Roque, Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark…, 1747. The eastward route of the correspondent of the Athenian Mercury, and the nine numbered locations, from Covent Garden [1] to the Royal Exchange [9], are indicated in red (click on image to expand it)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/map-of-London2.width-600.jpg)

'I was in Covent Garden 1 when the clock struck two, when I came to Somerset-house 2 by that it wanted a quarter of two, when I came to St. Clements 3 it was half an hour past two, when I came to St. Dunstans 4 it wanted a quarter of two, by Mr. Knib’s Dyal in Fleet-street 5 it was just two, when I came to Ludgate 6 it was half an hour past one, when I came to Bow Church 7, it wanted a quarter of two, by the Dyal near Stocks Market 8 it was a quarter past two, and when I came to the Royal Exchange 9 it wanted a quarter of two: This I aver for a Truth, and desire to know how long I was walking from Covent Garden to the Royal Exchange ?'

(Quoted from The Athenian Mercury, vi no 4, query 7, 13 February 1692/93).

Of mice and clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In his most recent blog, Oliver Cooke discussed watches and clocks without hands as indicators.

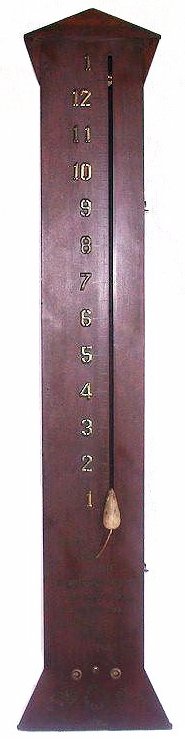

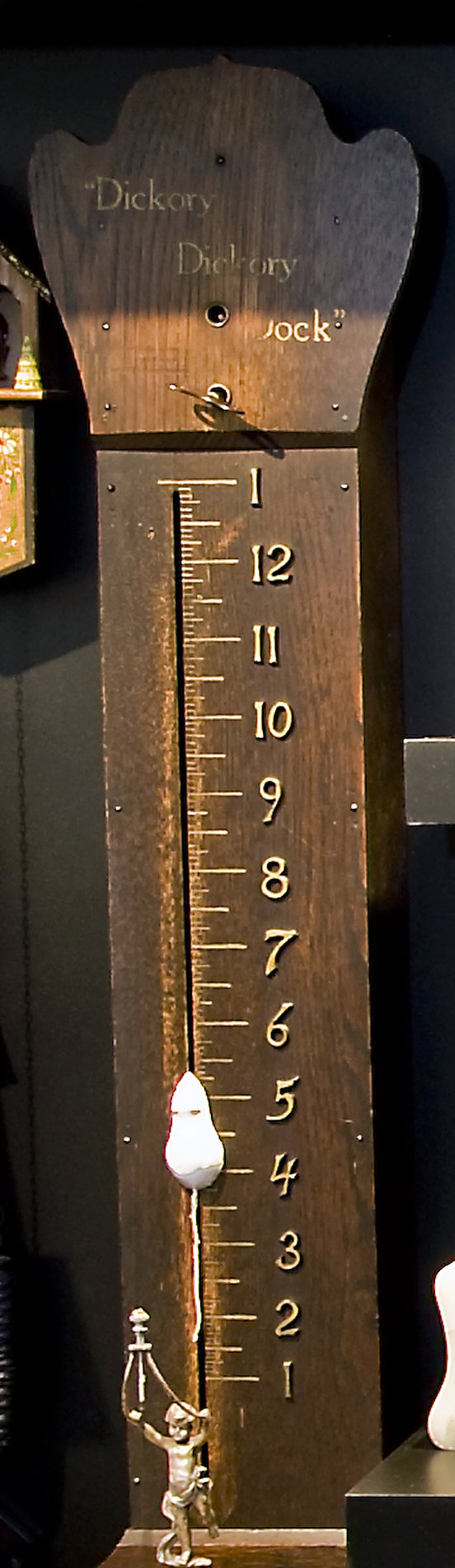

Another example is the Mouse Clock, in which a mouse making its way up against a wooden board serves as time indicator. Its designer was inspired by the well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickere, Dickere Dock

A Mouse ran up the Clock,

The Clock Struck One,

The Mouse fell down,

And Hickere Dickere Dock.

The rhyme comes in various versions; this is the oldest, published in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s_Pretty_Song_Book.

Could it be based on a real event: a mouse hiding inside a longcase clock, panicking when it struck?

In the literature I find only other explanations. One authority suggests it may be an onomatoplasm – an attempt to capture, in words, a sound; in this case, the sound of a ticking clock. Another relates it to the shepherds of Westmorland who once used ‘Hevera’ for ‘eight’, ‘Devera’ for ‘nine’ and ‘Dick’ for ‘ten’ when counting their flock.

Be that as it may, just over a century ago it inspired an American businessman, who was also an avid clock collector, named Elmer Ellsworth Dungan, to develop the Mouse Clock.

He initially just created one for his daughter, who loved the nursery rhyme, but then decided to take them into production. He took out patents and various models were manufactured.

They are nowadays prized by novelty clock collectors, so much so that we are warned to beware of reproductions, especially for what one dealer calls ‘Chinese knockoffs’.

Details, including several images of the mechanism, and a link to an animated photo of the clock in operation, can be found on these American websites: Antique Clock Guy and Fontaine’s Auction Gallery.

In 1966 the NAWCC published a booklet by Charles Terwilliger, Elmer Ellsworth Dungan and the Dickory, Dickory Dock Clock; there is a copy in the AHS Library at the Guildhall.

And speaking of mice and clocks, how about having some fun with the (grand)children with this on-line clock reading game. Read the time correctly and the mouse runs up safely to the cheese in the clock. Read it wrong and the cat gets the mouse.

Stopping the clock after death

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In a previous post I included an opera scene, in which a woman mentions (sings!) that at times she stops all the clocks in her house. She dreads getting old and wants time to stand still.

One reader told me this reminded him of a poem by W.A. Auden which begins:

'Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

'Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

'Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

'Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.'

But here the motive for stopping the clocks is different. Someone has died, and stopping the clocks in the house of the deceased, silencing them, is an old tradition, similar to closing the blinds or curtains and covering the mirrors. The clock would be set going again after the funeral.

Some people believe stopping the clock was to mark the exact time the loved one had died. The subject was discussed here by members of the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in America.

The French film Jean de Florette, set in the Provence between the wars, contains such a clock-stopping scene. The film is made after a novel by Marcel Pagnol, from which the following quotes are taken.

Jean, an outsider, inherits a house with surrounding land and hopes to make a living there. But two locals, who covet his land, secretly block a source, cutting off his vital water supply.

In despair, Jean uses dynamite to create a well, but he dies as a result of the explosion (chapter 37). The doctor, taking his pulse, 'listened for a long time in a profound silence emphasized by the ticking of the grandfather clock', but the man had died.

Then one of the two devious locals, who was in the room, 'crossed himself, walked around the funeral table on tiptoe, and stopped the pendulum of the grandfather clock with the tip of his finger'.

He then tells his comrade in arms 'Papet, I have just stopped the grandfather clock in Monsieur Jean’s house' – a way of saying: he is dead.

The three stills reproduced here are from that scene, which you can see in this short clip.

The clock is a typical Comtoise grandfather clock with a big flower pendulum.

Musical clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My previous post in this blog was on clocks in opera. How about opera in clocks?

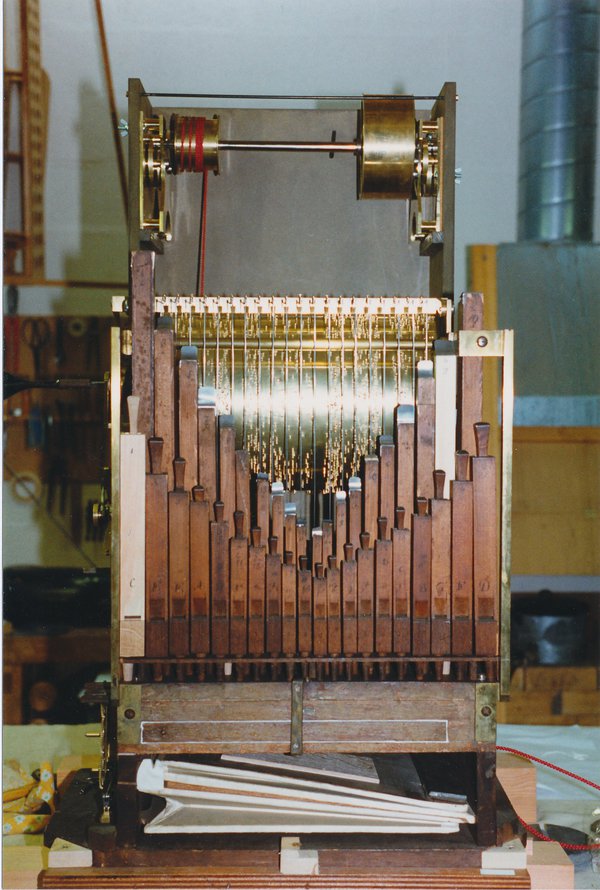

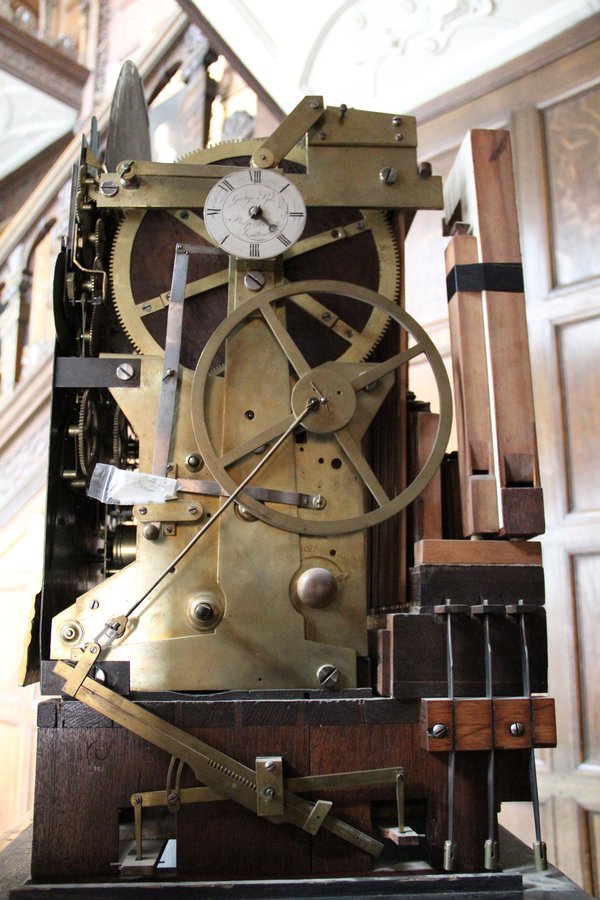

The Handel House Museum is the London home where the composer George Frideric Handel lived from 1723 until his death in 1759. In the 1730s, Handel provided music for a series of musical clocks created by the watch and clockmaker Charles Clay.

These more than man-sized, elaborate pieces of furniture were fitted with chimes and/or pump organs that at the hour and every quarter played musical excerpts from popular operas and sonatas.

Until 23 February the Handel House Museum presents an overview of Clay’s clocks in an exhibition ‘The Triumph of Music over Time’. The centrepiece is a clock on loan from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; other clocks are presented as photos on text panels.

These panels are all on-line here where you can also listen to some of the music that Handel arranged for Clay’s musical clocks, including two pieces from his opera Arianna in Creta. So there you have it: opera in clocks.

Another 18th century maker of beautifully crafted musical clocks was George Pyke. A fine example, dated 1765, is on display at Temple Newsam House in Leeds.

Standing over 6 foot tall on its pedestal, it strikes the hours and has a pipe organ that plays eight tunes. The innards of the Pyke clock are shown below; more photos and details of the clock are here on the website of Brittany Cox, who has made a condition study of the clock and hopes one day to be able to restore it to its former glory.

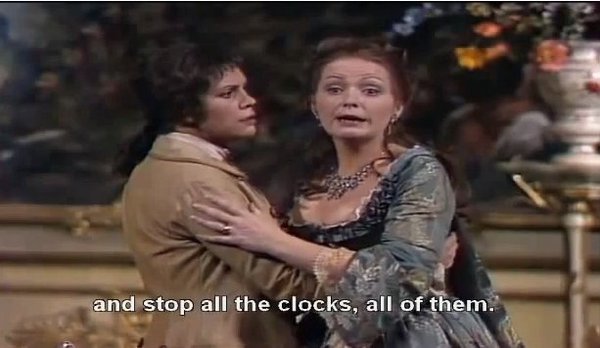

Although a bit off topic – it is not a clock – you may like to know of a musical automaton that Brittany Cox restored to working order during her studies at the Clocks and Related Dynamic Objects Department at West Dean College. A miniature ship, a mere 15mm wide, rocks to and fro, as in a storm, while ‘God Save the King’ plays on a plucked comb; see and hear it here.

For this project Brittany was awarded the annual AHS prize for 2012. For a full description see this article which she wrote for our journal Antiquarian Horology .

With thanks to Ella Roberts, Communications Officer at the Handel House Museum, for her help.

Clocks in opera

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

If you like music as much as horology (I do!), this is for you. For the links to YouTube you need a loudspeaker or headphones.

In Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi, the eponymous court jester hires an assassin to murder his employer, a plan that goes horribly wrong. He meets up with the assassin at midnight (‘mezzanotte’), punctuated by twelve strikes of the turret clock. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 46mins 20sec).

![Rigoletto: ‘The clocks strikes midnight’ – scored twelve times for the camp[ane], the tubular bells in the orchestra](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/bells-in-Rigoletto-Final-Act-1.width-600.jpg)

In Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca, Rome wakes up with the church bells sounding matins (early morning service). The instrument used in the orchestra is the tubular bells or chimes, metal tubes of different lengths hung from a metal frame, struck with a mallet.

The chiming is heard for more than two minutes, some bells sounding near, others in the distance. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 35mins36 sec).

Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov has a famous scene in which the Russian tsar has visions of the child prince he is suspected of having murdered. This is popularly known as the ‘clock scene’ and as there is no clock on stage nor in the text, this must relate to what goes on in the music.

Indeed, an obstinate, repetitive see-sawing theme is heard in the orchestra, but does it signify chiming or ticking? I am not sure. Watch it here (drag the timer to 0.58 for the ‘clock’ to start).

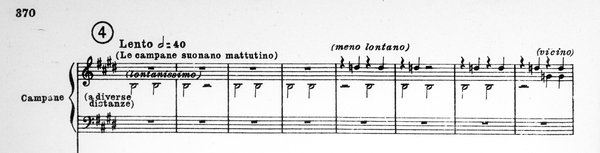

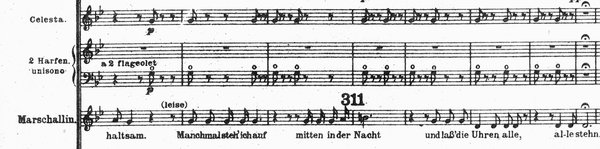

The most striking (pun intended) appearance of clocks in opera that I know is in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. An aristocratic lady has an extra-marital affair with a much younger man (sung by a mezzo soprano, one of the classic ‘trouser roles’ in opera).

Musing on how one day she will lose her young lover, as with the passing of time her charms will fade, she sings about the nature of time:

'Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding. Wenn man so hinlebt, ist sie rein gar nichts. Aber dann auf einmal, da spürt man nichts als sie. Sie ist um uns herum, sie ist auch in uns drinnen. In den Gesichtern rieselt sie, im Spiegel da rieselt sie, in meinen Schläfen fliesst sie. Und zwischen mir und dir da fliesst sie wieder, lautlos, wie eine Sanduhr. Oh, Quinquin! Manchmal hör’ ich sie fliessen – unaufhaltsam. Manchmal steh’ ich auf mitten in der Nacht und lass die Uhren alle, alle stehn'

or;

'Time is a strange thing When one is living one’s life away it is absolutely nothing. Then suddenly one is aware of nothing else. It is all around us, and in us too. It trickles across our faces, it trickles in the mirror there, it flows around my temples. And between you and me, it flows again, silently, like an hourglass. O, my darling, at times I hear it flowing – inexorably. At times I get up in the middle of the night and stop all the clocks, all of them.'

The music comes to a stand-still and all you hear is the chiming of a small domestic clock, played in the harps and the celesta – it’s magical. Watch it here sung in original German, with subtitles; drag the timer to 0.19.

A silent turret clock at the V&A

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum who notice the turret clock high up in the entrance hall find no explanatory label. Fortunately there is detailed information on the V&A website.

The 8-day turret clock with hour striking was ordered in 1857 for the newly created South Kensington Museum, as it was then named. It was made by J. Smith and Sons of Clerkenwell and cost £150: £110 for the clock and £40 for the bell and fittings.

A duplicate of the clock was later made by the same firm and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1862 (held on the site of the present Natural History Museum), where it gained a prize medal.

The two dials were designed by the artist Francis Wollaston Moody, who decorated much of the museum, and show allegorical figures.

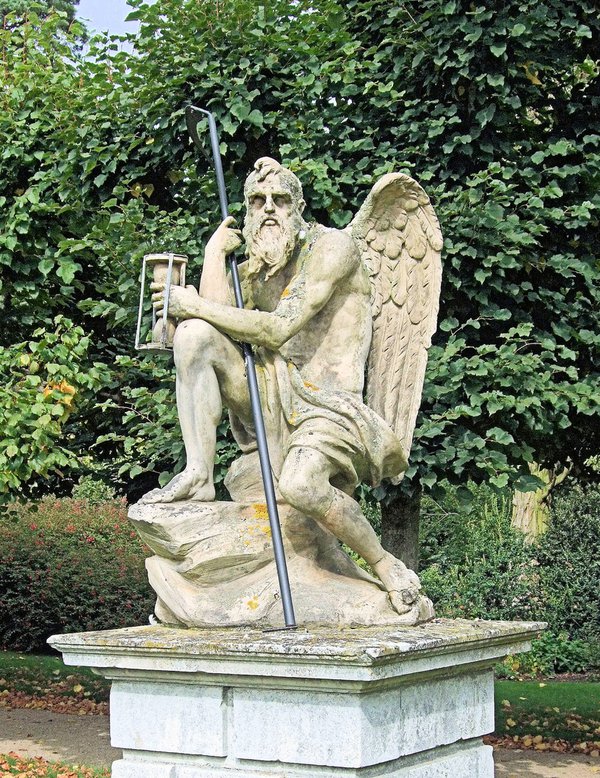

Day, in a chariot, is followed by a cloaked female figure representing Night; below it is the figure of Time with his symbols: hourglass and scythe. The irrevocability of time is represented by the letters of the word IRREVOCABLE spaced out between the Roman numerals.

To see it properly you need binoculars, but the photos reproduced here – as good as I could manage with a simple camera and amateur skills – give an idea of what the clock looks like.

In 1951 the clock was stopped and silenced, as it was cumbersome for a clock-winder to climb up a ladder, and the booming bell was thought a nuisance for the visitors. Later it was taken down and stored away.

But in the early 1980s it was put back in place, as it was considered an interesting object in its own right, and because of its association with the early history of the museum. It has been converted to electricity, so it shows the correct time even though the pendulum with its heavy spherical bob hangs motionless. But the bell remains silent.

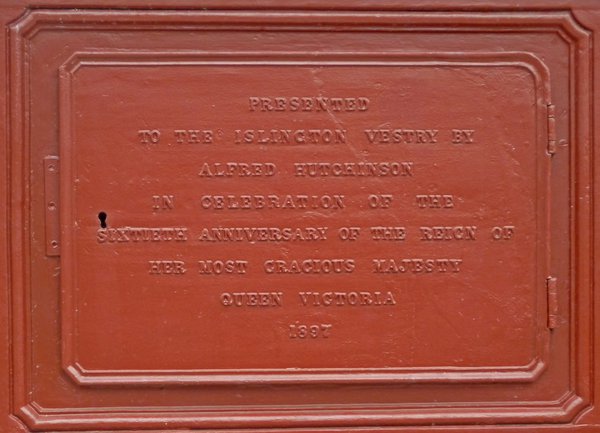

Clocks and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Cycling through north London I like to pass by the Jubilee Clocktower at Highbury, Islington, near the Arsenal football stadium. It was erected in 1897, sixty years after Queen Victoria came on the throne. And in the March 2011 issue of Antiquarian Horology we published a photo of a jubilee clocktower at East Harptree, Somerset, taken during one of the regional excursions of the AHS Turret Clock Group.

These are just two of what must have been dozens, perhaps hundreds, such clocktowers that bear witness to the commemorative zeal of the late Victorians. In February 1897, a specialist firm issued the following circular letter intended to generate new orders:

'We desire to draw the attention of the Nobility, Clergy, Gentry and others, who are contemplating the erection of Church and Turret Clocks in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, to our unrivalled facilities for manufacturing all kinds of clocks at the lowest possible prizes consistent with good workmanship and material, and to all requiring the same we would be glad to furnish estimates and information free of charge.'

Quoted from Michael S. Potts, Potts of Leeds. Five Generations of Clockmakers (Mayfield Book 2006), p. 133.

Many orders came in. The smallest clock tower that Potts installed in 1897 stands, fourteen feet high, on the town square of Much Wenlock, Shropshire.

Wikipedia has a list of jubilee clocktowers which also includes examples erected ten years earlier for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, like the one on the seafront at Weymouth, Dorset. They were also built in outlying parts of the British Empire. The Victoria Clocktower in Georgetown, Malaysia is still a well-loved landmark. It is sixty feet tall, one foot for each year of Victoria’s reign.

It would be great to have a proper study of these late nineteenth-century jubilee clocks and clocktowers, with a gazetteer telling us where they are, and of course who supplied the clocks. Something for a website, a book, or perhaps an article in Antiquarian Horology?

Big Ben and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The iconic tower that houses the world’s most famous clock has always simply been known as the Clock Tower, but was renamed Elizabeth Tower to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. Will the name catch on? I think that the man in the street, and that includes the tourists, will continue to call it the Big Ben, even though that was never the name of the tower, just the nick-name of the hour bell.

On 10 June I attended the launch of a guidebook published by the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and the Elizabeth Tower. It was great fun because it was held in the Palace of Westminster, in the opulent State Rooms in Speaker’s House, which outsiders don’t often get to see. The book is attractively produced and richly illustrated, and those wanting more can read Chris McKay’s book Big Ben. The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster.

Mr Speaker, John Bercow MP, addressed the guests, after which there were short talks by Mike McCann, keeper of the Great Clock, and Paul Roberson, one of the three clockmakers responsible for winding, servicing and repair of over a thousand clocks in the Palace of Westminster.

Between them, they also have to provide a 365 days a year out of hours call-out service should the Great Clock have a problem.

This illustrated article by Chris McKay reports on an overhaul of the Great Clock, undertaken in 2007 to correct wear problems. Paul Roberson, who is currently chairman of the British Clock and Watchmakers Guild, ended his talk with a joke that is probably as old as the hills but was new to me: 'What did Big Ben say to the Tower of Pisa? "I’ve got the Time, if you’ve got the Inclination".'

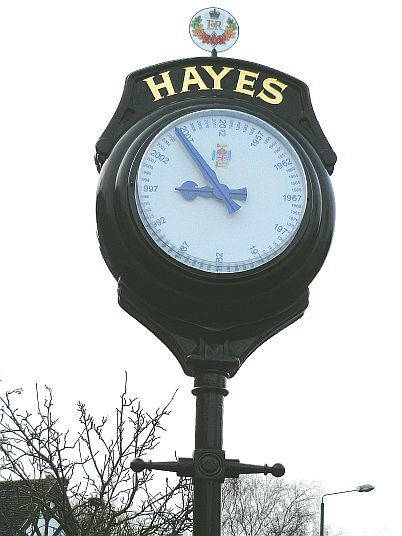

Elsewhere in the country the Diamond Jubilee has inspired modest horological activity. In February 2013 a jubilee clock was unveiled in Hayes in southeast London. The clock dial is made up of the sixty years of the Queen’s reign rather than minutes, with 2012 marking 12 o’clock.

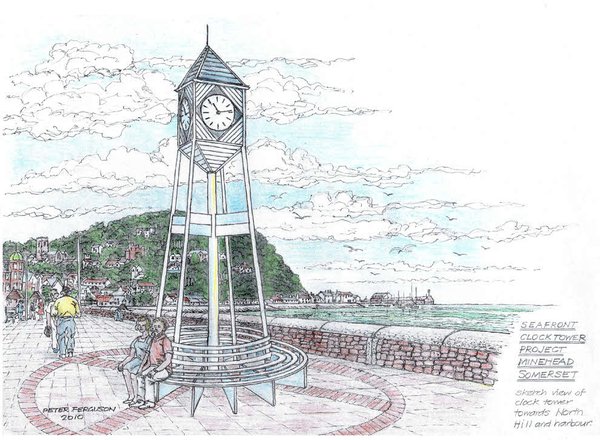

And in Minehead on the Somerset coast they hope to build an 8.5 metre tower with a four-sided display, with clocks on three sides and current tide times on the fourth. They still need donations to make it happen.

There will have been more initiatives. But it was nothing compared to the public clock ‘mania’ that erupted on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, which I shall discuss in my next blog.

Horological horrors

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

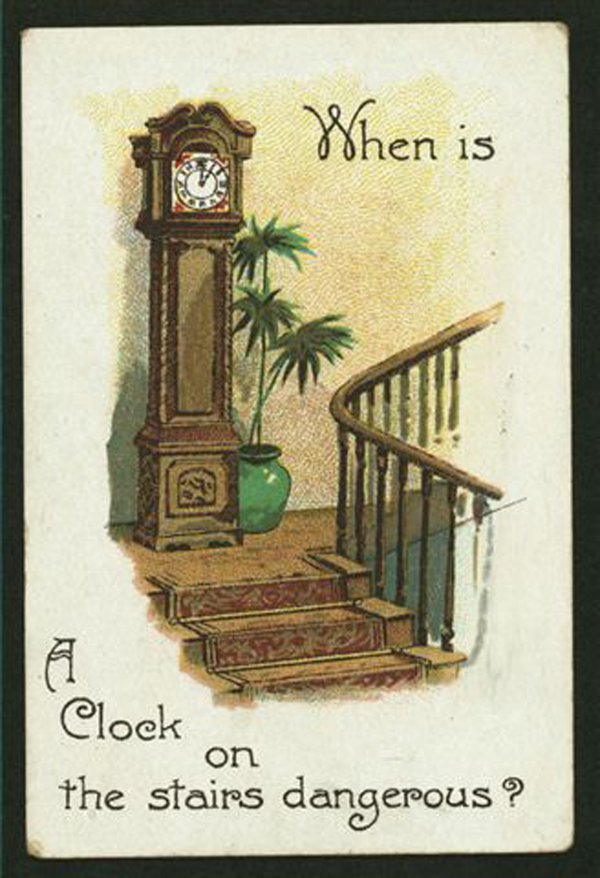

Browsing the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library I found a collection of cigarette cards, issued by tobacco manufacturers as an added incentive to buy their product.

On one of these cards we see a drawing of a longcase clock (the tall, standing type also known as grandfather clock) on a landing, with a riddle: ‘When is a clock on the stairs dangerous?’ The answer is printed on the back of the card: ‘When it runs down and strikes one’.

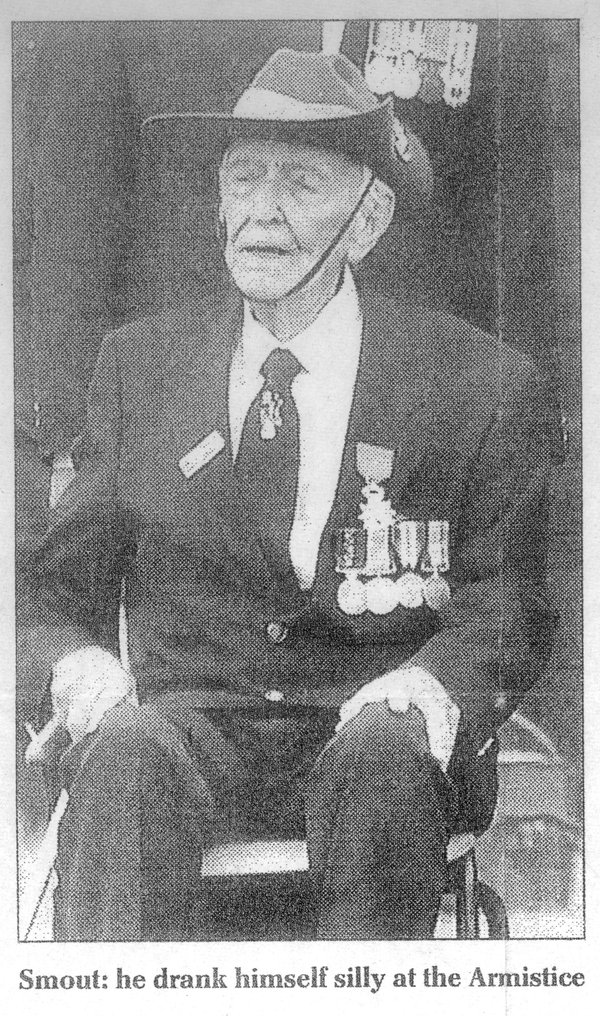

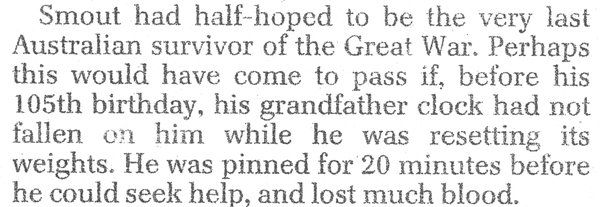

Jokes aside, longcase clocks can be dangerous, as one of the last Australian survivors of the Great War found out. When he died aged 106, the Daily Telegraph obituary had this lurid detail: two years earlier he had become trapped under his own grandfather clock when pulling up the weights. What an unexpected assailant for a veteran soldier! An AHS member sent me the clipping, after a neighbour of his had had the same misfortune. The lesson: make sure your longcase clock is firmly fixed to the wall.

Of course, there may be situations where you simply don’t have time to do that.

In his latest monthly column ‘Diary of a clock repairer’ in Clocks Magazine, Robert Loomes writes how he delivered a restored grandfather clock to a house in the countryside. Just as he finished setting it up, a squirrel ran into his trouser leg (you couldn’t make it up). Quite understandably, he stumbled and fell, and the assembled clock was dashed to pieces.

In September 2010, an AHS member in the Canterbury region in New Zealand wrote to me: ‘It was a sad day for unsecured longcases last Saturday. There was a major earthquake in Christchurch and at least two friends who had yet to screw new acquisitions to the wall had them tossed across the room and smashed.’

At my request, he wrote a short piece about it for the journal, and supplied a photo of one of the damaged clocks. Sadly, five months later a second, more destructive earthquake hit Canterbury, causing massive destruction and killing 185 people. In that light, it would have been insensitive to print the piece about damaged clocks. Fortunately I could just withdraw it before the journal went to the printer.

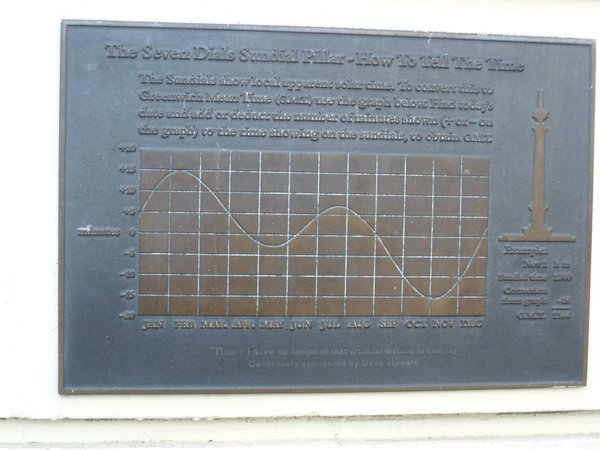

What became of the London sundial column?

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

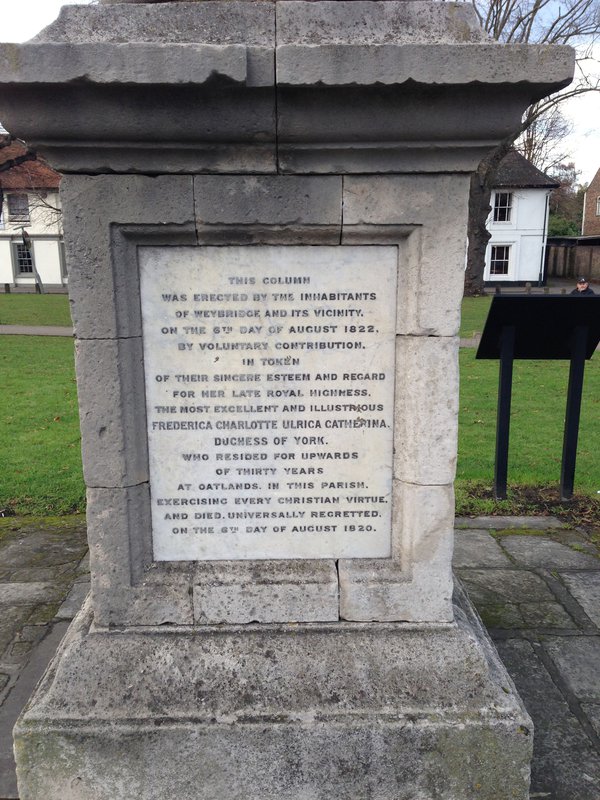

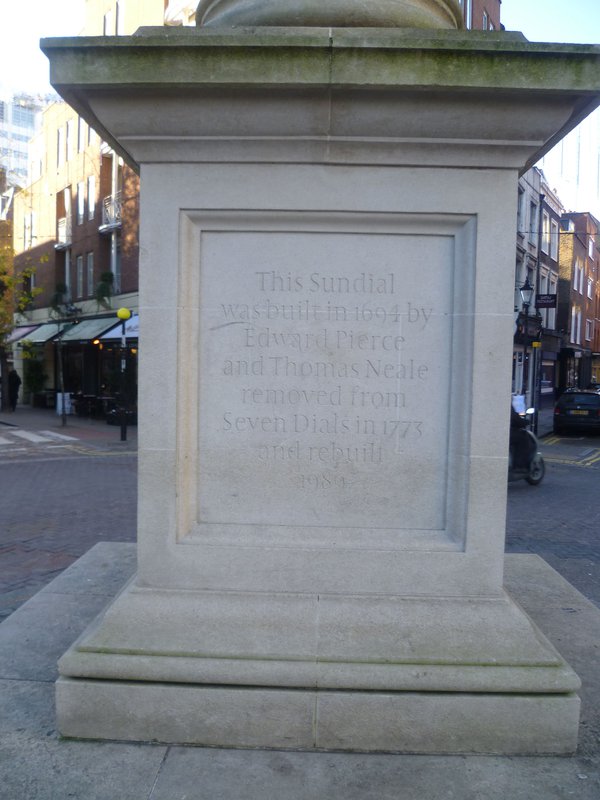

My previous blog was about the sundial column at Seven Dials in central London. It is a reconstruction, erected in the 1980s to replace a column that had been there since 1694 but was taken down in 1773.

Popular legend has it that it had been ruined by a search for treasure presumed to be buried under it. Perhaps more truthful is that it was removed because the place had become a meeting-point for riff-raff. Whatever the reason, it was demolished and its remains landed in an architect’s garden in Addlestone, Surrey, southwest of London.

But fifty years later it was given a new lease of life in nearby Weybridge. The column was erected by public subscription in 1822 in memory of Frederica, the Duchess of York (1767-1820) who had been a popular local benefactress. It was decided that the dial stone was too heavy to cap it. A ducal coronet was used instead and the base inscribed to the Duchess. Two centuries later, the York Column at Weybridge still stands on what is named Monument Green.

The original late 17th-century dial stone was used as a mounting block, to help the young or elderly or infirm to mount and dismount a horse or cart – not the best way to preserve a finely sculpted object. But this too has survived. More than three centuries old, and much the worse for wear, it lies to the west side of Weybridge Library. A plaque explains the historical significance of what to the average passer by must seem a very unassuming bit of stone.

My thanks go to AHS member Hugh Cockwill who lives nearby and took the photos at my request.

The sundial column at Seven Dials

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

As I live in central London, I often pass through Seven Dials, an area between the districts of Covent Garden and Soho where seven streets meet at a roundabout. In its centre stands a pillar or column with six vertical sundials at its top.

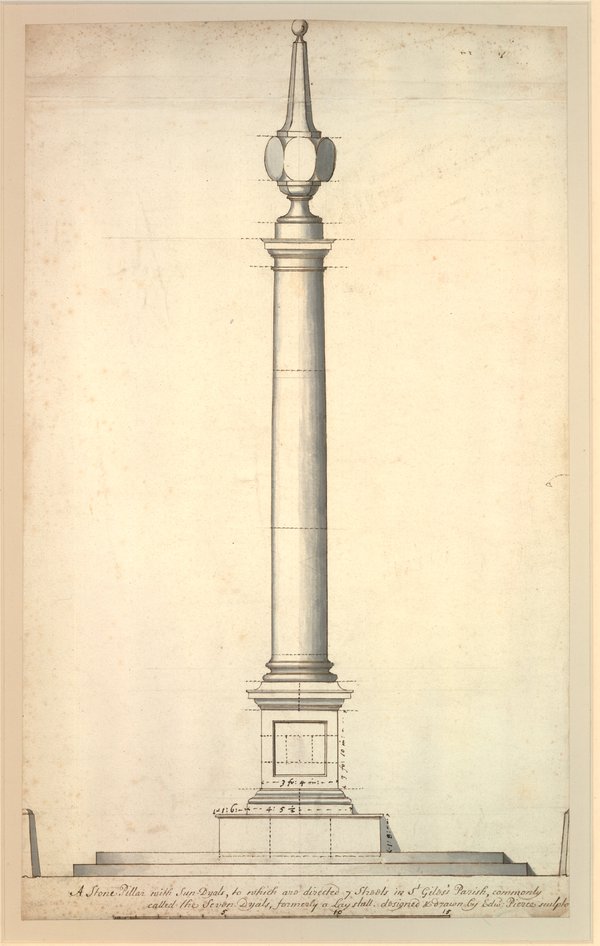

The area resulted from a building scheme of the politician-entrepeneur Thomas Neale MP (1641–1699), whose name lives on in nearby Neal’s Street and Neal’s Yard. He commissioned the architect and stonemason Edward Pierce to design and construct a sundial pillar in 1693-94 as the centrepiece of his development. Pierce’s drawing is in the British Museum and shows six sundial faces.

Why six, not seven? We are told that the column itself was the seventh, so it would act as style or gnomon, casting its shadow on the ground. If so, there must have been a noon mark somewhere. One thing is certain: the column never ‘supported a clock with six dials’, as the London Encyclopaedia tells us.

The column that we now see is not Edward Pierce’s original. That was removed in 1773 (in my next blog I will discuss what happened), and for two centuries there was nothing on the roundabout.

In 1984 a charity was set up (the Seven Dials Monument Charity, now Seven Dials Trust), who managed to raise funds to restore what it called 'one of London’s great public ornaments'.

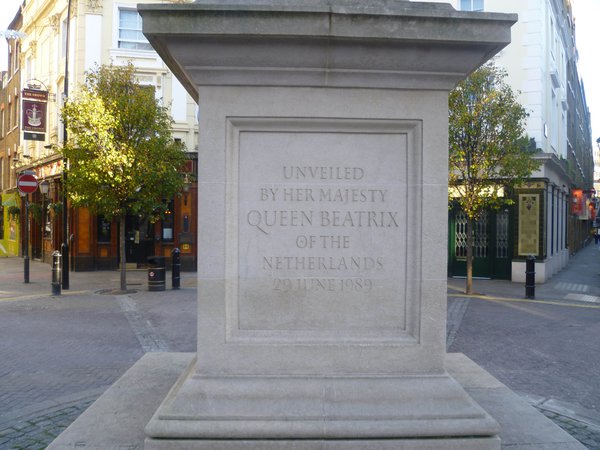

Five years later the new column was unveiled, complete with six new sundial faces in a striking blue colour. There is much explanatory information on and around the pillar. Do have a look when you are next in London’s West End.

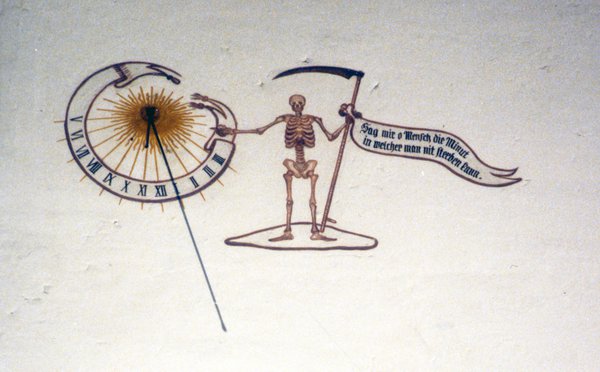

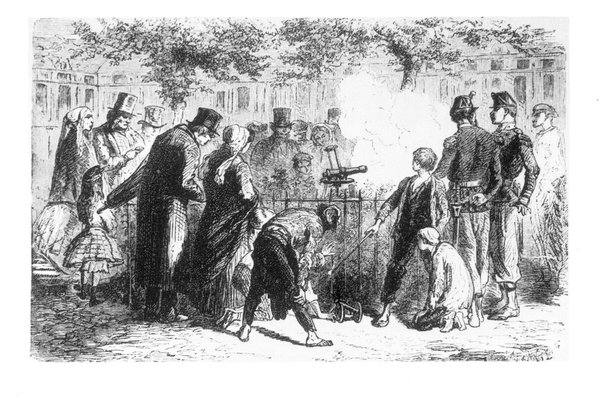

Sundials can be sobering and noisy

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Whereas a clock or a watch tells us at a glance what time it is, finding the time with a sundial is less easy. And it only works when the sun shines. Serious limitations, one might argue.

But this does not make them less attractive or fascinating. Indeed, there are societies entirely devoted to the subject, such as the British Sundial Society (BSS) whose members study and record old sundials and enjoy designing and discussing new ones.

Sundials come in many sorts. Like clocks and watches, they range from pocket-sized (Figure 1) to monumental (Figure 2), and from straightforward to mind-bendingly complicated.

What I like about them is that they can come with arresting imagery and texts. An example is the sobering memento mori we saw years ago on an Austrian church (Fig 3). The Grim Reaper would fit perfectly in the exhibition Death: A Self-Portrait, currently at the Wellcome Gallery in London.

Sundials are quiet. Not for them the reassuring tick-tack of a clock, or the quarterly or hourly chimes.

But there is one exception: the cannon dial, also known as solar cannon or noon cannon (Fig 4). It is fitted with a burning lens, so arranged that the Sun’s rays are directed to the touch hole of a small cannon. At noon precisely, it goes off with a bang! People could set their watches by it (Figs 5 and 6).

It was an acoustic variant of the Greenwich time ball, which for generations has been dropped every day at 1 pm sharp – initially for ships’ navigators to check their chronometers, and now purely as an enjoyable public spectacle.

Clocks in Berlin museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every year the AHS organizes a Study Tour for members to see collections of clocks and watches abroad.

The 2010 tour went to Germany and included two days in Berlin. As reported in Antiquarian Horology March 2011, they saw many fine clocks in the Charlottenburg Palace, as well as in the New Palace of Sanssouci in nearby Potsdam.

Last month I was in the German capital myself, and had a chance to visit some of the many other museums, and spotted further items of horological interest. The German Technical Museum has an impressive railway collection in two former loc sheds. In the entrance building they display the clock of the railway station of Breslau (now Wroclaw), dated c. 1850, complete with its vertical lead-off work and the dial. Next to it is an earlier turret clock, with stones as weights for the going and striking train, as well as – perhaps more unusually – for the pendulum bob.

Opposite Charlottenburg Palace is the Bröhan-museum, specialised in Art Nouveau, Art Déco and the Berlin Secession. Among the treasures of applied arts in ceramics, glass, wood and metalwork were two mantel clocks in Art Nouveau (also called Jugendstil) style, and a clock with ‘TEMPUS FUGIT’ (Time Flies) on the dial instead of numerals.

Any music lover will enjoy the Museum of Musical Instruments, located behind the famous Philharmonie concert hall and built by the same architect, Hans Scharoun.

Among the hundreds of historic instruments are two more than man-sized musical clocks. Both are among the dozens of instruments that can be heard on the audioguides supplied at the entrance. What a treat to hear these gentle sounds in the knowledge that traffic noise is just on the other side of the wall.

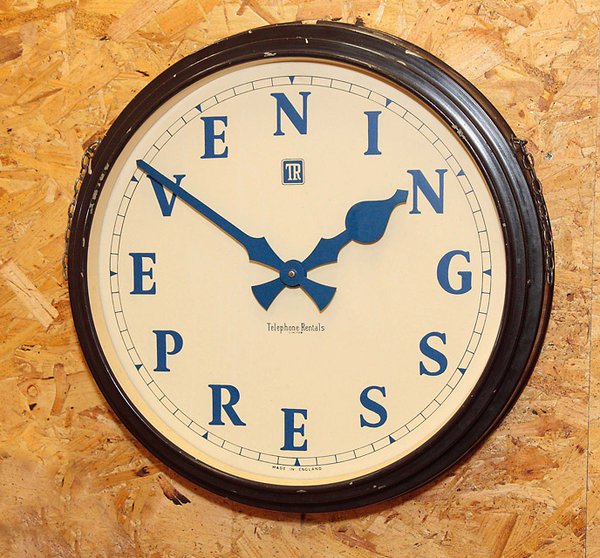

Letters on the dial

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

We are so used to telling the time from dials that we don’t really need the hour numerals. Some dial designs omit them altogether – distinctly uncluttered but also perhaps a bit dull. There is an alternative, which I find more fun.

Watches can be personalized by substituting the letters of the owner’s name for the hour numerals. As Cedric Jagger writes in his book The Artistry of the English Watch , this was by no means uncommon.

If the name did not have exactly twelve letters, the designer had to be inventive, as the three watch photos here demonstrate. The one with JAMES CATLING, dated 1814, gave no problems, but for GEORGE CATLING, dated 1815, NG had to be linked. On the other hand, for the eleven-lettered THO[MA]S STEVENS, dated c. 1840, the designer used a fox’s head at 12 o’clock.

Was this randomly chosen or was the owner perhaps an avid fox hunter?

At least two English churches sport a lettered dial. The one on St Peter’s Church Buckland in the Moor, Dartmoor reads ‘My Dear Mother’, and was commissioned by the man who donated the clock along with three new bells in 1931. And during a recent trip in Norfolk, the AHS Turret Clock Group saw ‘Watch and Pray’ on the dial of the clock at All Saints Church in West Acre.

These are the first words from Matthew 26:41, where Jesus is addressing his disciples on the Mount of Olives just before his crucifixion: ‘Watch and pray, that ye enter not into temptation: the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak’.

Finally, I was interested recently to come across this image of a mid-20th century electrical wall clock with special dial lettering and hands for the York Evening Press newspaper office, supplied by Telephone Rentals.

If you like this kind of thing, you may want to join a group of enthusiasts who share images and information online on just that: clocks and watches with letters. But on their database I do not see any longcase clocks with letters instead of numerals on the dial. So if you know of one, please leave a comment!

For use of their photos I thank three AHS members: Dave Stables (who published on the Catling watches in Antiquarian Horology of June 2011 and also online), turret clock specialist Chris McKay and the chairman of the AHS Electrical Horology Group, Martin Ridout.

The Silver Swan fictionalized

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The latest novel by the Australian author Peter Carey, The Chemistry of Tears, was inspired by the Silver Swan of Bowes project.

The Swan is an amazing late 18th-century, life-sized automaton, incorporating three clockwork mechanisms or movements, products of the clockmaking trade. It has been in the Bowes Museum in County Durham, Northeast England, since 1872 where it can be seen in action every afternoon.

In 2008, the Swan underwent a major conservation project, undertaken by our Council member Matthew Read. In 2010 he gave a fascinating talk on the subject for our Society, and recently he went back to Bowes to see that all was well, as reported in his blog ‘Friends Reunited’.

The story in the novel goes back and forth between the 19th century and the present. An Englishman commissions an automaton to be made in Germany. It’s inspired on Vaucanson’s famous digesting duck automaton, but somehow turns out as a (the?) swan – it’s all a bit unclear.

In modern London, a conservator in a fictional museum is given the task of restoring the by now dismantled automaton to working order. Her manager has set her this challenge, hoping it will take her mind off her grief over her lover’s sudden death.

Does it work as a piece of fiction? I am not sure. But what I am sure of is that there cannot be many novels that explicitly mention our journal:

'It was then, high on grief and rage, I stole two of Henry Brandling’s exercise books. What would happen if I was caught? Burn me alive, I didn’t care. I tucked them inside my copy of Antiquarian Horology, and walked straight past Security and out into the London street which was now, in late April, hotter than Bangkok' (p. 34).

If anyone knows another novel in which our journal occurs, please leave a comment!

A woman horological collector

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The AHS has recently paid attention to a number of Great Horological Collectors, with lectures that were later reported in the journal. All these lectures were about men.

That a woman could also assemble an important horological collection was demonstrated by the Austrian author Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830-1916). She had received practical training as a watchmaker and brought together a collection of 270 pocket watches dating 16th-19th century.

In 1917 it was purchased for the newly founded Wiener Uhrenmuseum, where the collection (sadly reduced to a mere 47 during World War II) is on display in a special room.

Her horological expertise and her love for her collection are reflected in her short novel Lotti die Uhrmacherin (Charlotte the Woman Watchmaker) of 1889.

Lotti is the daughter of a master watchmaker and is herself skilled in the craft. She inherits her father’s valuable collection of watches and refuses offers from other collectors, until her former fiancé gets in financial trouble. She relents and sells the collection, to be able to support him (anonymously).

Chapter 3 describes the collection in remarkable technical and historical detail, and names many makers – Le Roy, Breguet, Tompion and Mudge, to mention just a few.

Further reading: Eva-Maria Orosz, ‘“My watches make it hard for me to die”. Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach: the writer as watch collector’, pages 10-13 in Highlights from the Vienna Museum of Clocks and Watches (Vienna, 2011); I thank Fortunat Mueller-Maerki for bringing this essay to my attention. There is no English translation of Lotti die Uhrmacherin , but a freely downloadable edition with some English annotation is on-line here.

Scientific instruments on a watchcase

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Only a very small selection of the British Museum’s vast collection of watches is on display. Fortunately many more are described and illustrated in the museum’s online collection database, free for all to browse and explore. Visit www.britishmuseum.org > Research > Collection search, type in the word ‘watch’ and you get 6634 results!

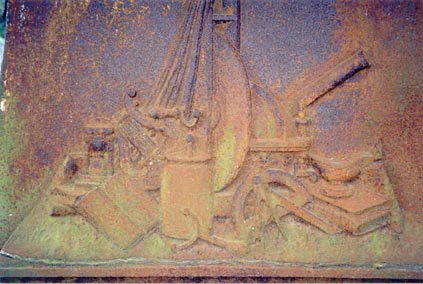

Of course there are ways to limit your search. One watch that caught my attention was this gold cased, month-going cylinder watch by Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807), one of the most celebrated watchmakers in eighteenth century France. My special interest was the image on the back of the watchcase (Fig 1).

To quote the museum’s description: 'The design on the back – incorporating a universal equinoctial ring dial signed "OV BION A PA", an armillary sphere, a pair of dividers, a telescope, a microscope and a book – indicates that the watch was intended for a customer with scientific interests'. In fact, we discern one more instrument: an air-pump as used in physics experiments, as famously captured by Joseph Wright of Derby (Fig. 2).

As my professional background is in the history of scientific instruments, I find this watchcase of great interest. It reminds me of similar ‘group portraits’ of instruments that can occasionally be found on gravestones or funerary monuments in old cemeteries.

One example is this cast-iron funerary monument erected for a Dutch amateur of the sciences (Fig. 3). For details see this short article in Dutch; an English version appeared in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society Vol 69, June 2001, but is not available online.

If anyone knows other examples of scientific instruments depicted on a clock or a watch, please leave a comment, as I would love to know.

A clock striking thirteen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Clocks strike the hours one to twelve and then start all over again. And yet, in a church tower near Manchester there is one that strikes thirteen, and has done so for over two centuries.

The idea of a clock striking thirteen times is a recurrent theme in literature.

Famously, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) begins: 'It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.' And in Philippa Pearce’s classic children’s book Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) a longcase clock striking thirteen inspires the boy to leave his bed and to step into the nineteenth century in a sun-lit garden.

The theme also comes up in history and in legends, and examples are quoted on Wikipedia. Some must perhaps be taken with a pinch of salt, but one that is most definitely true came up in a recent article in our journal.*

The authors live in Northwest England and are members of the AHS and meet fellow enthusiasts regularly in the Society’s Northern Section. In this article they discuss a clockmaker who worked in the region roughly in the age of Napoleon, and trace big turret clocks that can be linked to him, either as maker, installer or repairer.

A famous character in the history of the region was the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater (1736 –1803), known as the Canal Duke. His first canal was constructed to carry coal from the mines on his estates in Worsley to the markets in Manchester.

In 1789 he had a tower built to house what became known as the ‘Bridgewater Clock’. I now quote:

'There is a well known legend that the Duke witnessed his workers returning late after a lunch break. On asking them why they were late, the men complained that they could not hear the clock strike one above the noise of the yard. The Duke then promptly asked a local clockmaker to alter the clock so that it would strike thirteen at one o’clock. […] The clock remained in the tower at the Works Yard until the site was demolished in 1903.'

The clock eventually ended up in a London cellar, but was returned to Worsley in 1946 to be installed in St Mark’s Church, which then celebrated its centenary.

Unfortunately, the church is just a few metres from the M60 and a very busy intersection, so one has to strain to hear the clock above the road noise. But the evidence of the hands pointing to one o’clock and the thirteen strikes is there for all to see and hear, as can be witnessed in This short video.

* Steve and Darlah Thomas, ‘William Leigh of Newton-Le-Willows, Clockmaker 1763-1824: Part 1’, Antiquarian Horology , Vol 33 no 3 (March 2012), pages 311-334 .

With thanks to Steve and Darlah Thomas, Chester, for the information, photos and video.

The smallest clockmaker’s workshop in the world

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

What I like about museums is the same thing I like about public parks. You can go in and be happy without having to worry about costs, upkeep and security, as private collectors or garden owners have to.

What’s more: entrance to many of the best museums is free. Deciding to walk in and have a look is just as easy as taking that walk in the park.

There are many museums with historic clocks and watches, and those in Great Britain are listed on the AHS website. There are enough to keep you busy for a long while.

If you are in the City of London, for example to see St Paul’s Cathedral, why not also take a look in the nearby Clockmakers’ Museum at Guildhall. Gathered in one ground-floor gallery you will find the treasures assembled over the years by the honourable Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. It was established in 1631 and is still active, which makes it the oldest surviving horological institution in the world.

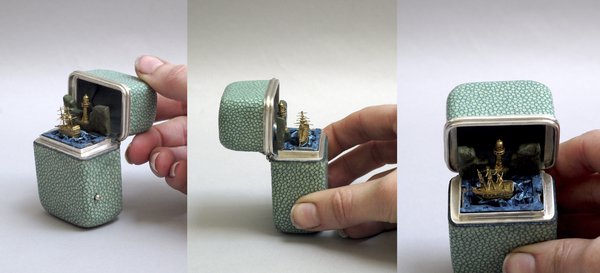

Among my favourite showcases is the one filled with horological curiosities [Fig 1]. The object at the bottom is a model of a clockmakers’ workshop [Fig 2]. It was made around 1930 by the London antique dealer Percy Webster, who was Master of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1926 – they have a new Master every year!

It is indeed a curiosity, as it is not known why it was made, nor what period he intended to represent. But it’s fun to kneel down and look at this horological equivalent of a doll’s house. The only thing missing is the miniature clockmaker himself.