The AHS Blog

Watching over us

This post was written by David Thompson

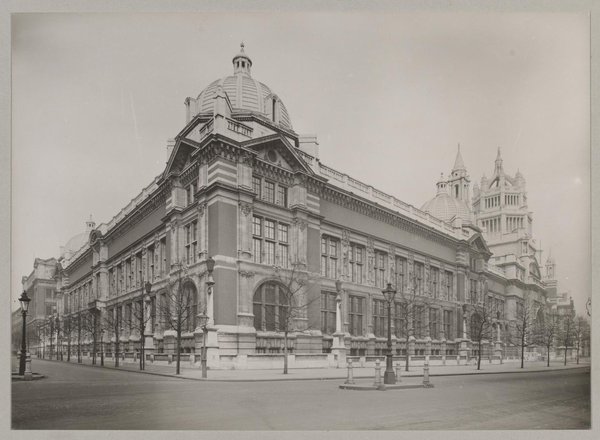

Walking up Exhibition Road in London on the way to the Science Museum, you just have to look to your right and up a bit, and there stands one of our great horological giants.

On the façade of the Victoria & Albert Museum stand a cohort of celebrated figures in Britain’s manufacturing heritage. Thomas Tompion is there amongst some illustrious company.

On his left and right are St. Dunstan, the Patron Saint of craftsmen, sculptor William Torell, printer, William Caxton, goldsmith George Heriot, blacksmith, Huntingdon Shaw, cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale, potter, Josiah Wedgwood, bookbinder, Roger Payne and designer, William Morris.

These figures, finely sculpted in Portland stone, make up part of the museum’s façade designed by Aston Webb and begun in 1899 when Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone.

However, it was not to be until 1909 that King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra officially opened the new building.

The figure of Tompion was sculpted by Abraham Broadbent (1868-1919).

He was born in Shipley, the son of a stonemason. He studied in London at the South London Technical School of Art and went on to become one of the more celebrated sculptors of his time, particularly in works in the baroque style.

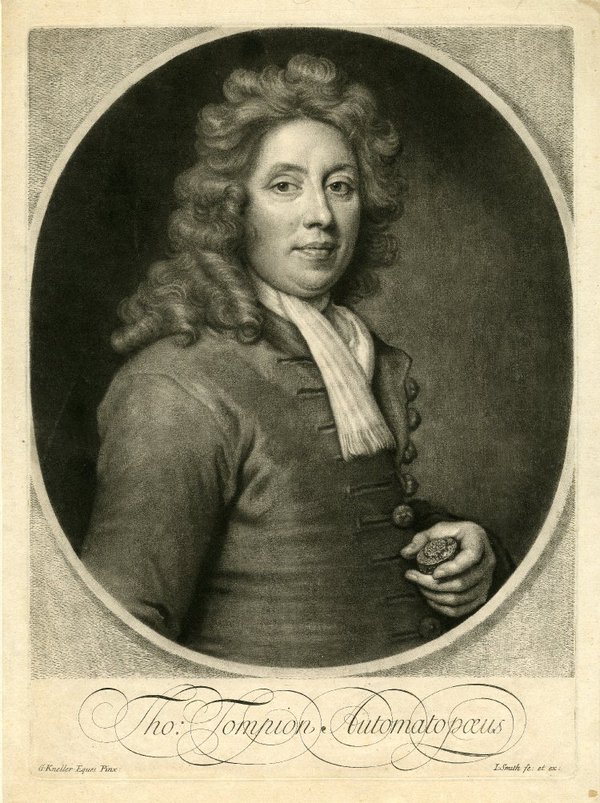

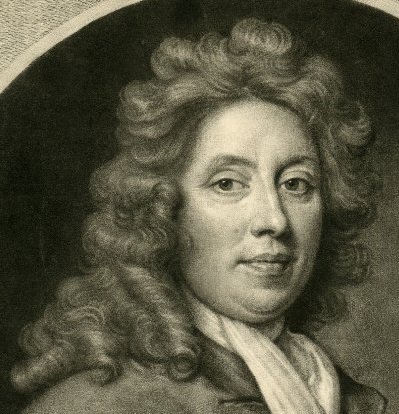

Looking at Broadbent’s image of Tompion, however, it would seem that he had no access to the well-known mezzotint portrait of Tompion by John Smith after a portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Tompion is depicted holding a watch in his left hand, and what appears to be a magnifying glass in his right hand. It would seem that Broadbent did not discuss his proposed figure with a watchmaker, even in the late 19th century, such a visual aid was not the preferred instrument.

Nevertheless, it is great to see that one of the clock and watchmaking giants is there amongst a pantheon of recognized celebrities.

For a detailed account of all the Victoria & Albert Museum sculptures around the building façade, see http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/misc/va/facade.html

Permission to come aboard

This post was written by David Thompson

All made in the 1580s, there are three surviving clock-automata in the form of medieval ships, made by Hans Schlottheim in Nuremberg.

One, a silver nef made for the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

A second, larger and more elaborate example in gilded copper exists in the Musée de La Renaissance in the Chateau d’Écouen near Paris.

The third example similar in many ways to the Écouen nef, resides in the British Museum.

These automata ships were made as table decorations designed to trundle along the banquet table playing music and firing their cannons at the end of their performances. What a way to impress your dinner guests in the 1580s.

Looking at the British Museum nef, it is clear that, with the exception of just one figure standing on the upper rear deck, all the figures on the ship are more recent cast copies of this one original.

One of the problems with automata such as this is what happened when they went out of fashion. Clearly such a thing could not be shown as an impressive demonstration of wealth at banquets time after time.

It is known that the Augustus, Elector of Saxony (1526-1586) had one of these table entertainments – there is a detailed description of just such a machine in the inventories of the Elector’s Kunstkammer from the 1580s. But what happened later?

You can just hear one of the guests at a second outing of the nef saying 'come on Augustus, we’ve all seen that, don’t you have anything new for us?'

When the nef, became less of a wonder and more of a curiosity, you can imagine a small child insisting that the figures be removed so that they could be played with individually. After all, the machine itself had ceased to function properly years ago.

This is speculation of course, but it might well explain the absence of figures on the ship when it appeared in England in 1866 and was bought by Octavius Morgan MP who then gave it to the British Museum.

Intriguingly, in 1983 a figure came up at auction in London and investigation suggested that there was every possibility that the figure was an original from the nef in the British Museum.

It was purchased by Rainer Zeitz Limited, but when they heard about the possibility that it came originally from the British Museum nef, they very kindly donated it to the collections.

For more information on these wonderful machines, see:-

http://musee-renaissance.fr/objet/nef-automate-dite-de-charles-quint

http://www.khm.at/en/visit/collections/kunstkammer-wien/

Julia Fritch (ed), Ships of Curiosity , Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2001.

Time in Old Bohemia

This post was written by David Thompson

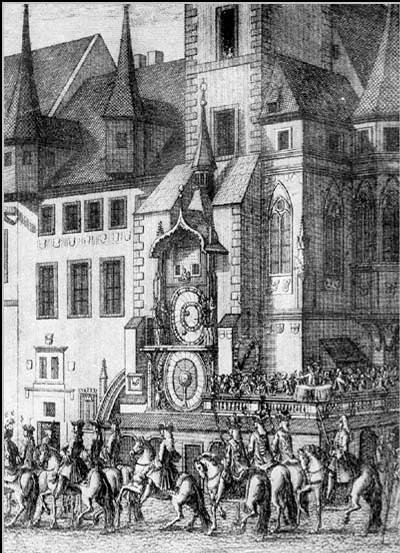

Many thousands of people today have stood amazed in front of the Astronomical Clock in the Old Town Hall Square in Prague, but I wonder just how many have managed to make sense of the dial. In modern times, perhaps it makes little sense.

The clock was made by Jan Šindel in about 1410, and from as early as the 15th century, the clock had a 24 hour dial which showed the so-called Bohemian Hours, a system in which the day began and ended at sunset.

This means, of course, that the 24-hour ring around the outside had to be adjusted periodically so that the 24th hour coincided with sunset.

In the early part of the clock’s life this was done manually, but later an automatic mechanism was installed to adjust the position of the ring. In medieval Prague, a knowledge of how long it was to sunset and the imposition of curfews in the city was useful knowledge. For instance – a simple glance at the dial indicating 19 hours tells you straight away that it is five hours to go before sunset.

As well as telling the time, the dial also has moving sun and moving effigies of the sun and moon, showing where in the zodiac they lie throughout the year. Useful astrological information.

The ecliptic circle with the zodiac signs and the sun and moon effigies rotate together once per day, but gradually over the course of the year, the sun and moon effigies with make a complete circle of the zodiac.

All this is achieved by some sophisticated gearing located behind the dial and driven by the clock mechanism in the tower. With the horizon circle with shaded buff areas, the periods of Aurora and Crepuscular, dawn and dusk are also shown,

Today, the clock is controlled by a more modern ‘regulator clock made by Romuald Bozek in the 1860s, but for the most part, the clock mechanism is still that which has been in existence from the beginning of its history.

Looking at the illustration here, you will see that the time is just a few minutes past 13 hours. On the fixed chapter circle the time is shown just before IX o’clock in the morning and hour 24 is just before 8 o’clock in the evening – correct for a July date. The sun is in Leo and the moon is in Aries.

So next time you stand in front of this amazing clock, you can really show off by knowing how to read the dial.

The Battle of the Three Emperors – or the Battle of the Three Dates

This post was written by David Thompson

I was recently reading Dušan Uhlír’s book The Battle of the Three Emperors and I came across an intriguing fact about the battle of Austerlitz which took place on the 2nd December 1805 between the armies of Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire Empire and Tsar Alexander I of Russia against their invading enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte.

In Uhlír’s fascinating account of one of the most famous battles of the Napoleonic campaign, excepting Waterloo of course, he points out that the battle took place on a different day for each of the three armies.

For Francis II, the date was 2nd December 1805, for Alexander and the Russian army the date was 20th November and for Napoleon, Bonaparte it was 11th Frimaire year XIV.

Francis and his army were using the Gregorian calendar introduced in 1582, although it was not universally adopted throughout Europe – indeed, England didn’t change until 1752. Alexander was still using the old Julian calendar – the Russians did not change to the Gregorian calendar until 1918. Napoleon was using the French Revolutionary Calendar, introduced in 1793, but back-dated to September 1792 to mark the beginning of the new republic and each successive year numbered from then on.

It must have caused some confusion for the Austrians and the Russians when agreeing a date to face up to Napoleon and the French would have had to convert the traditional dates into their new scheme.

The sands of time

This post was written by David Thompson

Everyone is familiar with the egg timer, but just how far back in history do these glass timers filled with free-flowing material go?

The earliest known illustration of such a device exists in an Italian fresco dating from between 1337 and 1339 in the Palazzo Publico in Siena. The fresco is called ‘The Allegory of Good Government’ and in it, one of the figures can be seen holding a sand-glass.

Before modern glass making techniques developed, sand-glasses were made using two separate bulbs bound together around a disc with a hole for the ‘sand’ to pass through. Over the centuries all manner of different materials were tried in attempts to achieve a uniform free-flowing performance.

The duration of the timer depended firstly on the amount of ‘sand’ in the glass, and secondly on the size of the opening between the two containers. The two glasses were sealed together with wax and the joint covered and tightly bound. The biggest enemy for these glasses was humidiy – damp ’sand’ was bad for business.

A particularly fine example exists in the British Museum collections, although is has a rather dubious reputation.

It is a composite glass with four separate glasses in a beautiful ebony frame and each glass is designed to run for a different period, one quarter, one half, one three quarters and last a full hour. It even boasts a leather carrying case.

At one time it was said to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots and indeed, at the top and bottom of the frame are reverse-painted glass discs bearing the royal shield of the Tudors and the shield of France with fleur-de-lys. The idea was that this glass was owned by Mary Queen of Scots and Francis II, king of France.

Unfortunately, the Tudor arms are from the wrong period and the lion rampant in the first quarter of the shield is the wrong way round. The leather case is also roughly embellished with the monogram MF for Mary and Francis.

In spite of its later enhancement, this is nevertheless a very fine example of a late 17th century glass.

If only I knew what the right time is

This post was written by David Thompson

When you want to know the correct time today, you either look at your mobile phone or you look at your radio controlled clock watch or listen to the six pips on the radio. However, don’t do the last one on digital radio as it is quite a bit out of sync with the real time – about two seconds.

Before the introduction of telegraph time signals and the distribution of time, everyone had to rely on a local observation of true solar time – that is, the time shown on a sundial.

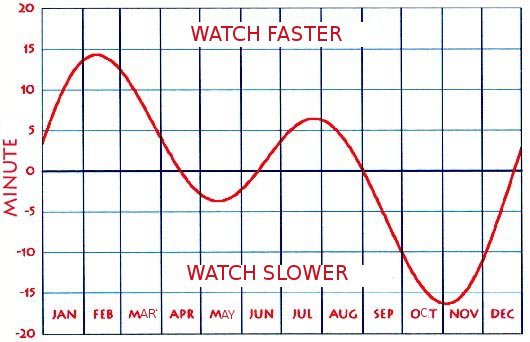

Unfortunately, the mean time shown by a clock and the true time shown by a sundial don’t agree throughout the year. Because the earth’s orbit around the sun is elliptical and because the earth’s axis is tilted to the celestial plane by 23 ½ degrees, the sundial (showing apparent or true solar time) and the clock (showing mean solar time) can be different by as much as 15 minutes.

There are four days in the year when the clock and the sundial agree with each other – 15th April, 13th June, 1st September and 25th December.

Until 1657 and the introduction of the pendulum, real time didn’t matter much as clocks were so inaccurate that the variations between true and mean time were irrelevant to all except astronomers.

The application of the pendulum to clocks made them capable of much more accurate timekeeping and the same was true when the balance spring was added to the watch in 1675 – measuring time to within a minute a week.

So, in order for an owner to put his clock right by a sundial, he had to know what the difference should be between his sundial reading and the time shown on his clock.

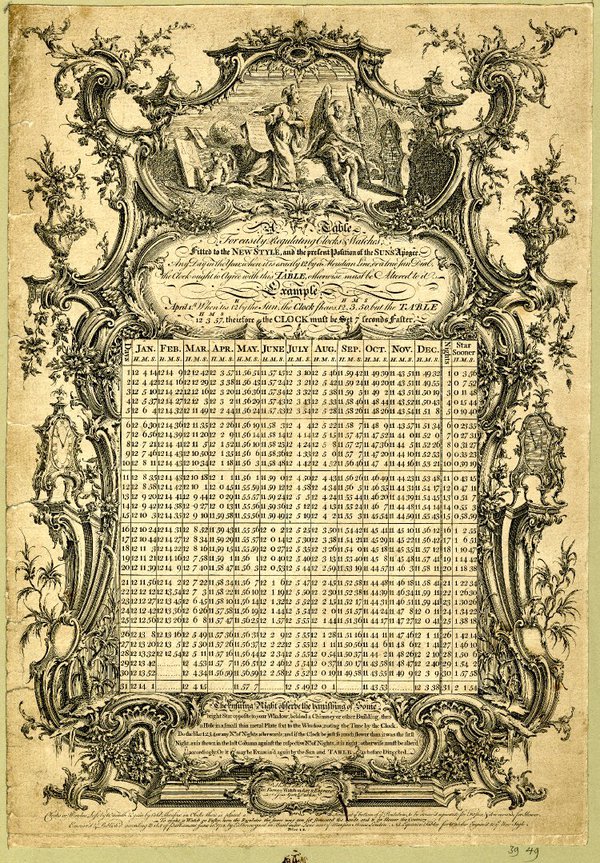

From the latter part of the seventeenth century, tables were published which gave exactly that information. The table shown here is devised so that when a clock is checked at noon, the table shows what time the clock should show.

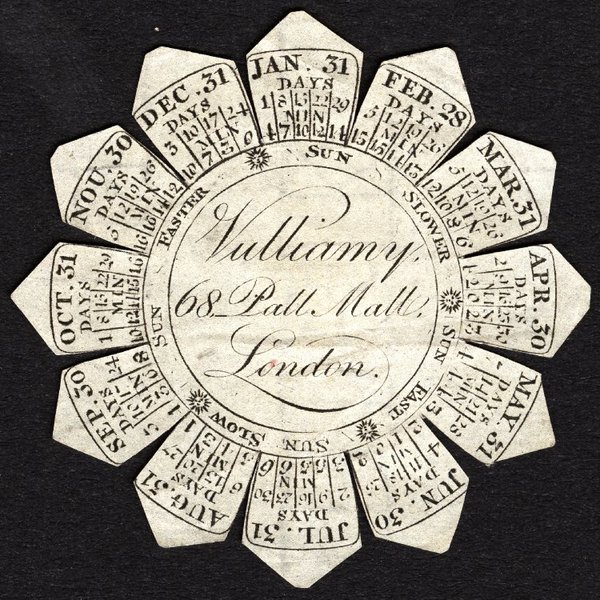

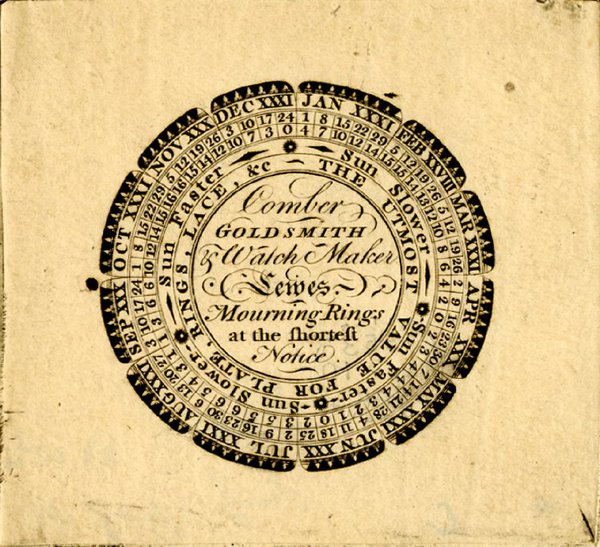

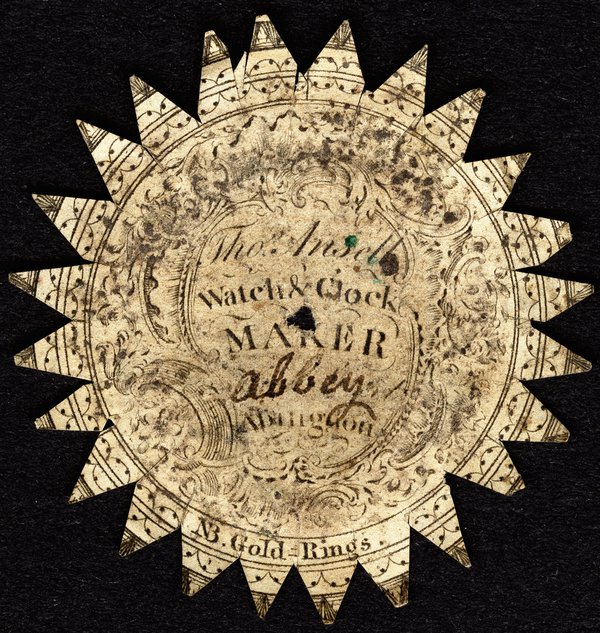

From the later part of the 18th century watchmakers would add a circular advertising paper into the outer cases of pair-cased watches and many of these had the equation-of-time table printed on them for easy reference.

Such papers were produced by top London makers such as Vulliamy in Pall Mall and by provincial makers such as Richard Comber of Lewes in Sussex. It was probably Comber’s customers who needed a table more than someone in the centre of London where the church bells offered a huge variety of ‘right’ time. It is worth bearing in mind, too, that the adjustments could only be done when the sun was shining!

Wake up – tea’s up

This post was written by David Thompson

What a treat to be able to wake up in the morning to a ready-made cup of tea and to be grateful to a machine for producing it automatically. Many of the older generation will remember a machine for just that purpose, a machine which was always referred to as the Teasmade.

Probably the one we all remember was the Goblin Teasmade but there were many others and the originally idea has its origins at the end of the 19th century with Mr. Rowbottom’s 1891 patent – with an automatically lit gas burner to heat the water in the kettle and then the machine would pour the boiling water into a tea-pot to make the tea, I can just see the warning notice on such a machine today – well not really as such a fire hazard would not be put into manufacture today.

There is a fine example of an Albert E. Richardson machine in the Science Museum to give an idea of what the early machine were like.

I was intrigued by this subject from seeing the Teasmade on exhibition in the British Museum clocks and watches gallery and it lead me to a splendid account of the history of the automatic tea maker written by David Stoner and published as a chapter in Clifford Bird’s book on Metamec, published by our own society and still available today at a give-away price.

All the original machines were clockwork, controlled by a simple alarm clock mechanism so you got the wake-up bell and the ready-made cup of tea, almost guaranteed to be luke warm. Many people swore by them and I don’t doubt at them. Nevertheless, a great idea.

Just so you know how rich I am

This post was written by David Thompson

Today some people wear expensive watches partly to demonstrate their wealth. They either sparkle with diamonds or they impress with their complexity of mechanical magnificence. You might think that this is a new idea, but in fact this tradition goes back centuries to when the first watches were made in the early part of the 16th century.

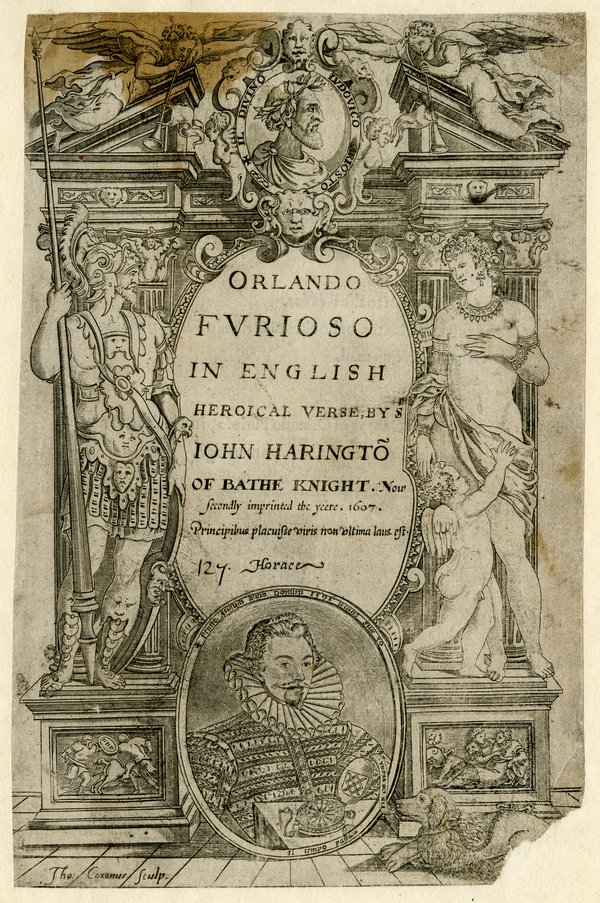

An interesting example of this comes from the title page of Sir John Harrington’s translation of Orlando Furioso, (The Frenzy of Orlando, an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto first published in 1516.) Harrington’s translation, which appeared in 1591 was the first in English. The story contains politics, war, religion and unrequited love as well as fantasy and consists of forty-six eight-line verses in rhyme – quite a challenge for the translator.

On the title page of the work is an engraved portrait of Sir John proudly sporting a fine oval-cased watch with the Harrington shield of arms engraved inside the cover. The portrait is dated 1st August 1591 and bears the inscription ‘Il tempo passa’ and the legend that Sir John was thirty years old when the portrait was taken – time passes and this is a moment in the life of the author.

A similar watch can be found in the British Museum collections, made by an immigrant Flemish worker in London, Ghylis van Gheele and here too, the watch sports a shield of arms, This time of the Giffard family of St. Andrew’s Abbey in Northamptonshire.

In late Elizabethan England what better way to show everyone just how wealthy and successful you were.

‘I didn’t see him take anything, but they’re not here now’

This post was written by David Thompson

'Lost out of Mr. Garon’s shop on Monday the 14th instant, a gold watch, hook chain and seal all gold, on the dyal plate Garon London, one silver watch the name Garon London, another silver watch the name Clyet Landon: If the said watches be brought to be sold, pawn’d, valued or amended, you are desired to stop the goods and party, and send word to Mr. John Milburn a watchmaker in the Old Baily, and you shall have 6 guineas reward or proportionable for any part, or if brought to the said Mr. Milburn, the party shall receive 6 guineas, and shall have no questions asked'.

Politicus Mercurius, London, 17th-19th November 1709

Advertisements such as this are common in the London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne (1703-1714) and every one tells a tale. Just what happened here where Mr. Garon had three watches stolen from his shop we don’t know, but by any account the event was unfortunate.

Whilst this watch by Peter Garon is not the gold one described, there is no doubt, judging from this example, that a Garon watch was not something anyone would want to lose. The tortoise-shell (turtle) outer case inlaid with gold wire is a work of art in itself.

Peter Garon was a Huguenot who was formerly known as Pierre Garon and he had something of a chequered career. Brian Loomes in Early Clockmakers of Great Britain gives the following account.

Peter Garon was apprenticed to Richard Baker in April 1687 and finished his term in 1694. However, because he was still an alien, he was refused freedom by the Clockmakers’ Company but the Lord Mayor of London did grant that freedom in the same year. He became a Freeman in the Clockmakers’ Company in August 1694.

In October 1696 he admitted forging the name of a Mr. Legrand on a watch of his own making. In 1697 he was warned about taking unofficial apprentices and by 1709 he was clearly in trouble again.

'Whereas the acting Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt awarded against Peter Garon of London, watch-maker, have certified to the Right Honourable the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that the said. Peter Garon, both in all things conformed himself to the late Acts of Parliament made against Bankrupts: This is to give notice that his certificate will be confirmed as the said Acts direct, unless cause be shewn to the contrary on or before the 2d of March next.'

London Gazette 7th-10th February 1709

Note. We are hugely indebted to W.R. and V.B McCleod and John R. Milburn (no relation to the above) for their researches into the lost watch advertisements in London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne.

Japanese time

This post was written by David Thompson

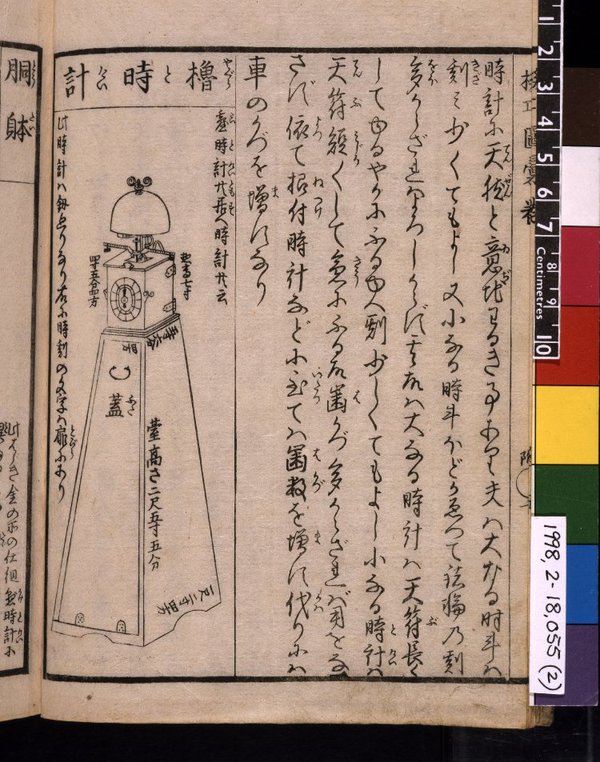

From the first appearance of the clock in Japan, when the Spanish Jesuit priest, St Francis Xavier, arrived with gifts for the Emperor, including at least one clock, in 1551, the story of mechanical timekeeping in that country has been an intriguing one, and one which lasted until the end of the Edo dynasty in 1873.

From 1612, when the Europeans were expelled from Japan and the country was closed to outside influences, the Japanese clockmakers were on their own for over 250 years. What they produced in terms of clocks was indeed ingenious.

First of all, how was time measured in Japan in that period? Take the hours of darkness and divide those up into six equal parts. Then take the hours of daylight and also divide those up into six equal parts and there you have it. Clearly if the day is divided in this way, the length of the daylight periods and those of darkness will vary throughout the year except at the equinoxes when all the hours will be equal and equivalent to two hours of European time.

Unfortunately, mechanical clocks like to keep equal unchanging hours as best they can. So, what did the Japanese clockmakers do in circumstances where they had no access to what was going on in far distant Europe at the time?

Three quite effective methods were devised to get round the problem:

- to have two separate oscillators in the form of weighted swinging bars known as foliots with adjustable weights to change the rate of the clock.

- to have moveable markers either on a round dial or on a flat bar, depending on the type of clock.

- to have a series of plates, usually fourteen, which would be changed periodically depending on the time of year.

In all three types the time indication would have to be adjusted twice per month.

When it came to style, there were basically three types of clock in Japan:

- the stand or lantern clock, weight-driven and either mounted on the wall or placed on a stand.

- the table clock, designed to be placed on tables or on a suitable place in an alcove.

- the pillar clock, specifically made to hang on the thin wooden pillars which made up the framework of the inner paper wall of the house.

In the early period, the oscillating foliot was used as the timekeeping element, a single one in the earliest clocks and a double in the later, more sophisticated examples. As the technology progressed, pendulums or oscillating spring balance wheels were used – a larger form of the device found in mechanical watches.

Such clocks were only owned by the wealthy and were perhaps more used as status symbols than they were to tell the time and organise the household.

The dog watch

This post was written by David Thompson

Anyone with connections with the sea and ships will tell you that the dog watch is a period of service between 4.00pm and 8.00pm and that it is split into two watches, the first and second watches on board ship.

Today there are any number of charms for bracelets and pendants in the form of dogs and I don’t doubt that there were all sorts for sale at the recent Crufts dog show. How many would guess, however, that you could buy a watch in the form of a silver dog in the 17th century.

A unique example exists in the British Museum collection where a silver-cased watch in the form of a dog can be found. The watch maker was Jacques Joly who lived in Geneva between 1622 and 1694. He made this watch in about 1660. It was during the middle period of the 1600s that there was a fashion in watches looking like real and animate objects, tulips, fritillary flowers, sea urchins and so on.

If the little dog needed a friend, there is a charming little lion living in the collections in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, this one with a movement made by Jean Baptiste Duboule. Of interest to both the dog and the lion is a little cast silver watch in the form of a hare which was stolen some years ago from the Musée de L’Horlogerie in Geneva. It has a movement inside signed, P. Duhamel, Geneva, and, as far as we know, a unique example of a watch case in that form.

Stand up for watches

This post was written by David Thompson

Today we all take the ownership of a plain ordinary watch for granted and such watches are easily purchased at easily affordable prices. The same is true of the cheap and simple clock, be it a wall clock for the kitchen or a carriage clock for the shelf or mantel.

From the latter part of the 17th century until the end of the 19th century it has been possible to purchase a stand which enabled the owner to transform the watch into either a wall clock or a shelf clock simply by placing the watch in a specially made case.

Examples vary in shape and size, but two relatively rare ones are shown here. The first is a splendid tortoise-shell and ebony-veneered stand which can either be wall mounted or table standing. It is designed with an opening front to enable a common pocket watch to be placed inside to perform as a clock. It was made in England in about 1690-1700, and is enhanced by a portrait bust of King William III surmounted by a crown on the front brass decorative panel.

From a similar period is a French example which has a characteristic so-called ‘boulle’ case.

The technique of inlaying brass into tortoise-shell was pioneered in Paris by Charles André Boulle 1642–1732 and in consequence this type of work is named after him, although there were many workshops in Paris using this amazing technique. The material actually used was not tortoise but commonly hawksbill turtle. In some instances the craftsman would make use of the negative and here the pattern on the back is the negative left from producing the brass inlays for the front.

In contrast to these two elaborate and relatively expensive watch stands, lastly is a 19th century stand consisting of a simple folding wooden box which would allow an ordinary watch to be placed on a bedside table for night use.

Time to pay

This post was written by David Thompson

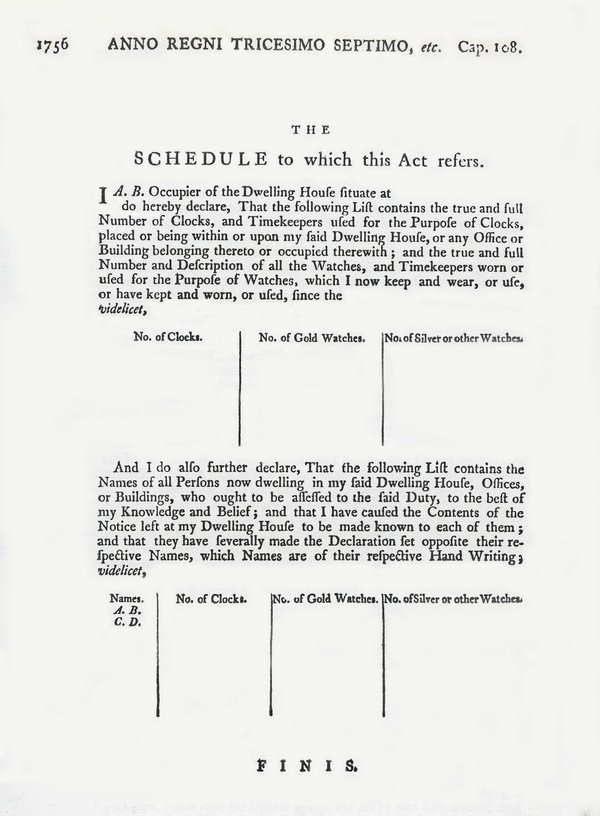

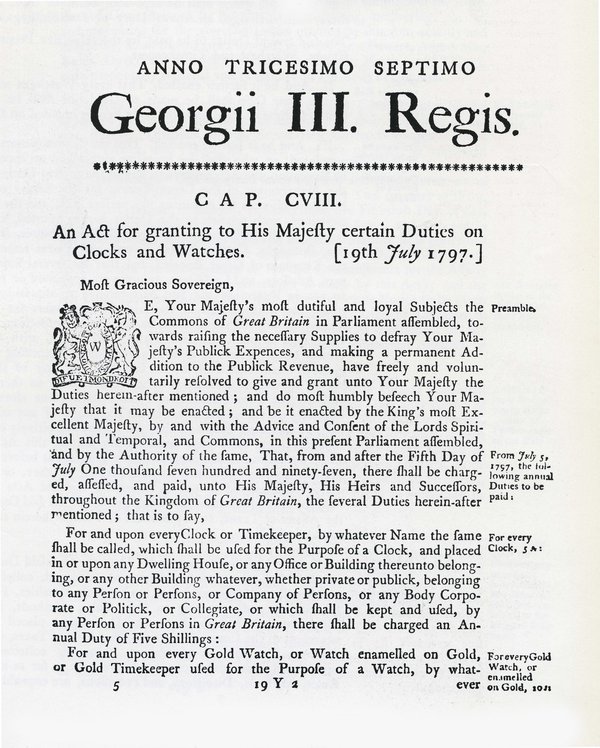

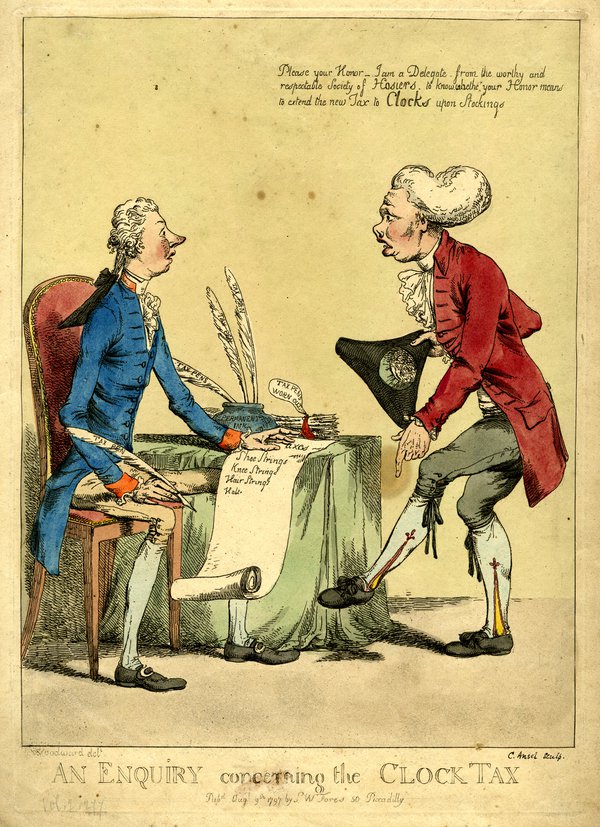

With all the current talk about taxation, I am reminded of a futile attempt to raise money introduced by William Pitt in 1797. Now commonly referred to as the Clock Tax it involved the levy of charges for clocks and watches under an act which was put into effect on the 5th July 1797.

Under the act, levies would be charged at the rate of 5 shillings for every clock and 10 shillings for every gold cased watch or a watch with a case enamelled on gold. Silver and base-metal cased watches would incur a charge of one shilling and six pence. Householders, tenants and businesses alike were to provide a signed declaration of all the clocks and watches in their possession for the purposes of assessing the amount to be paid. Inspections would be made and the taxes levied according to the number of items.

Of course, people hid their clocks and watches and made false depositions to such an extent that the whole idea became unworkable and was quickly abandoned.

At the time of the tax a rather splendid satirical print was made suggesting that as the tax was something of an absurdity, perhaps the government were considering levying a tax on the embroidered decorations on stockings which are called ‘clocks’. The coloured print was made by A.C. Ansell in the style of the well known caricaturist George ‘Moutarde’ Woodward and published by S.W. Fores of 50 Piccadilly, London, on 9th August 1797.

With the increasing use of mobile phones as time-tellers, perhaps the answer today is a tax on these ubiquitous items!

(Thanks to Marjorie Hutchinson for timely advice)

A pointless exercise

This post was written by David Thompson

Sometimes, ideas were way ahead of their time and when they were first thought up they had no application. Subsequently, however, the concept became a popular and widely used one.

Today with frequent and easy air travel, as well as instant communication around the world, the appearance of a world time dial on a watch makes perfect sense and indeed such dials are common. A simple Google search for ‘World Time Watch’ brings up over 2 million references.

What use would such a watch be in the second half of the 18th century.

Imagine a man-about-town in London showing off his latest purchase to his friends and being proud of the fact that he could tell them what time it was on other parts of the globe. When any communication with such places would have taken months at least, you can just hear his friends saying,‘fascinating, but what’s the point – and where is Antiqua anyway?

Nevertheless such watches did exist in the mid-18th century and one example survives to this day in the British Museum Collections.

It is a gold pair-cased watch made by John Neale in London in 1770. It shows the time in London, Mexico, Persia, Antegoa, Russia, Italy, China and other exotic places. It was probably sold as a gimmick, as something out of the ordinary and a curiosity which didn’t need to have a purpose – just a bit of fun for the owner who could say ‘did you know………….?

Where on earth have you been?

This post was written by David Thompson

Sometimes watches have a particular association with a particular person and we know about from an inscription written somewhere on it.

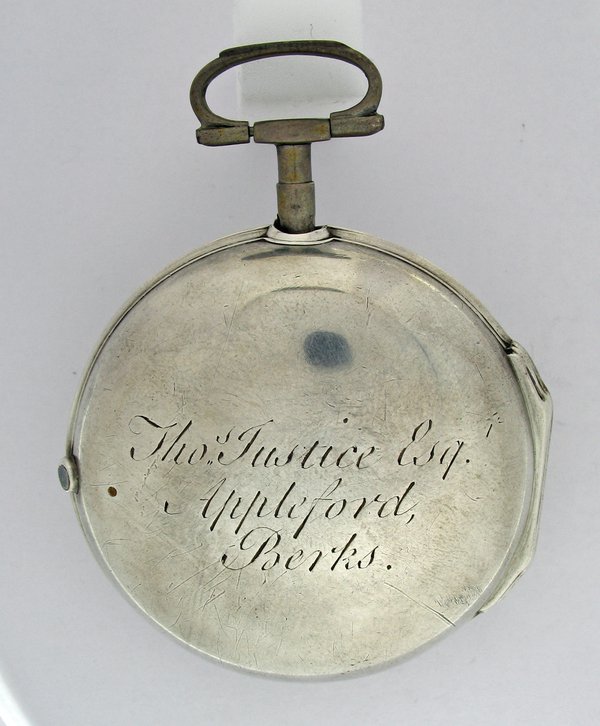

This particular watch, by Samuel Toulmin of the Strand in London, made in 1775, has a finely engraved inscription on the back of the outer case, ‘Thos Justice Esq. Appleford Berks’. There was a Thomas Justice of Appleford who is described as having died of ‘intemperance’ in September 1789. Could he have been the first owner of the watch who had it inscribed on the back in 1775?

Further information about an owner of the watch appears on an advertising paper inside the case. The information on the paper tells us that by 1822 the watch was in Abbingdon, in Berkshire, where it was looked at by Thomas Ansell near the Abbey – presumably a routing clean and re-oil. We are fortunate that an inscription on the reverse of the paper reveals the name of its owner at that time as Mr. Thomas Justice, Appleford.

On Wednesday 20th January 1830, a group of properties in Appleford, Sutton Courtney, formerly owned or rented by Thomas Justice were auctioned at the Crown & Thistle in Abingdon. It may be that Thomas was trying to realise some cash. On Monday 8th February 1830 a petition was heard at court in Portugal Street, Lincolns Inn Fields, London, concerning the Insolvency of one Thomas Justice, late farmer of Appleford.

In the church of St. Peter & St. Paul in Appleford is the following memorial:-

'In a vault near this church lie interred the remains of Thomas Justice Esquire, late of this parish who departed this life on the fourth day of January 1843 aged 54. Also of Martha Justice reliat of the above who departed this life on the 8th day of September1848 aged 59. Also of Thomas Francis Justice, Esquire, son of the above. Who departed this life on the 13th day of January 1847 in the 28th year of his Age.'

There’s a lot more to say about the Justice family of Appleford but it’s amazing what can be found on the internet in a very short time.

Lighting up time

This post was written by David Thompson

The story of the night clock, a device which allows the time to be seen in the dark is a long one.

In this modern era of instant electric light, it is easy to forget that in earlier times, getting light at night was quite an involved business. So what better way to solve the problem than to have a clock which was illuminated all through the hours of darkness.

One of the earliest examples of these clocks was that invented by the Campani brothers, Giuseppe, Pietro Tomasso and Matteo Campani from San Felice in Umbria, who worked in Rome in the second half of the 17th century.

However, one clock which caught my attention was a much later, metal cased clock in the form of a Greek urn in which was placed a light source –oil lamp or candle, and which had a system of lenses to project an image of the dial onto a wall in the room.

The clock was made and retailed by the inventor and optical instrument maker Karl August Schmalkalder, born on 29th March 1781, in Stuttgart, Germany. He came to England in about 1800 where he anglicised his name and in later years worked in partnership with his son John Thomas Schmalcalder. On his retirement in 1839 the business was continued by his son.

Charles Augustus married Charlotte Ann Cochran on May 24, 1804, in St Andrews church, Holborn and he died on December 25, 1843 in the Strand Union Workhouse – although he is renowned for his patented prismatic compass, a mechanical drawing device, optical instruments and barometers, sadly his genius did not make him a rich man.

Whilst the Schmalcalder name appears on the clock dial where he describes himself as ‘Patentee’. I have failed to find a patent in that name for this device – it may be that he is simply telling his customers that he is a holder of patents not specifically for this illuminating device.

For a detailed account of the Schmalcalders, although without detail of this clock see – Julian Smith, ‘The Schmalcalders of London and the Priddis Dial’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Volume 87, No.1, 1993, pp. 4-13.

For more information on the Charles Augustus Schmalcalder, see the family history website created by Steve Smallcalder.

Money saving time

This post was written by David Thompson

There would be a knock at the door and my mother was busy. She would say 'that will be the insurance man – answer the door and give him this money and tell him the number is 16251'.

Many of us remember these numbers rather in the same way that anyone who did national service or served in the regular armed forces will surely remember their ID number.

In 1954 the Time Savings Clock Company Limited and Metamec of Dereham applied for a patent for a clock which would only go when coins were placed in a slot in the top of the case. Two florins weekly it says on the coin slot in the case top.

For people on insurance schemes with companies like the Co-operative in the 1950s, four shillings was quite a lot on money to put aside each week. The idea of the clock was to help people hold on to their money to pay the premium each week.

The system was invented by William Arthur Pitt and the patent was granted to the Time Savings Clock Company of Manchester (no.772,762). The mechanism consisted of a series of levers and wheels which arrested the going of the clock to which it was fitted until coins were inserted to release it and thus allow the clock to run.

These coins, after operating the levers would fall into the space at the bottom of the clock case, covered by a wooden panel which fitted over a stud and was closed by a wire and lead seal applied by the insurance man. When he called he would cut the seal, empty out the money and re-seal the back until his next visit – simple.

A full account of these clocks and many more everyday clocks can be found in Clifford Bird’s book – Metamec Clock Maker Dereham published in 2003 by the Antiquarian Horological Society.

Horology in action

This post was written by David Thompson

Mechanical clocks turn up in the most unlikely situations.

When thinking of the Battle of Britain and the courage of the airman who flew Spitfires and Hurricane in defence of Britain in 1940, the humble clock does not immediately come to mind as playing a part in active service. However, selected aircraft in squadrons were fitted with a signalling device which allowed the controllers at strategic airfields to plot the position of fighter aircraft and so direct them to intercept approaching enemy aircraft.

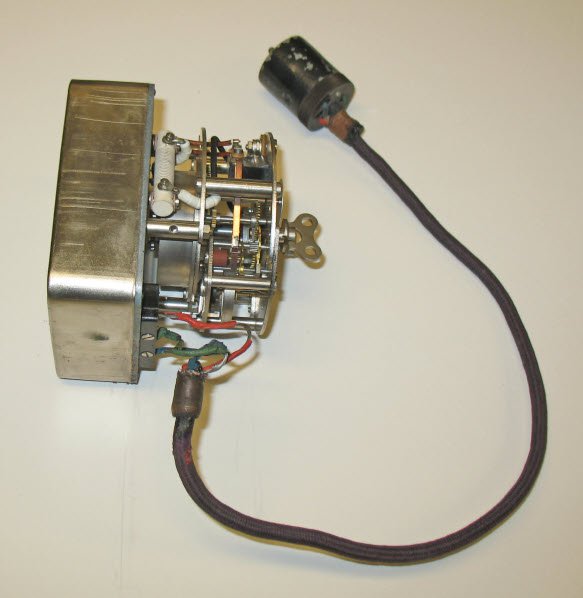

The system used by the Royal Air Force was commonly known as 'Pipsqueak'.

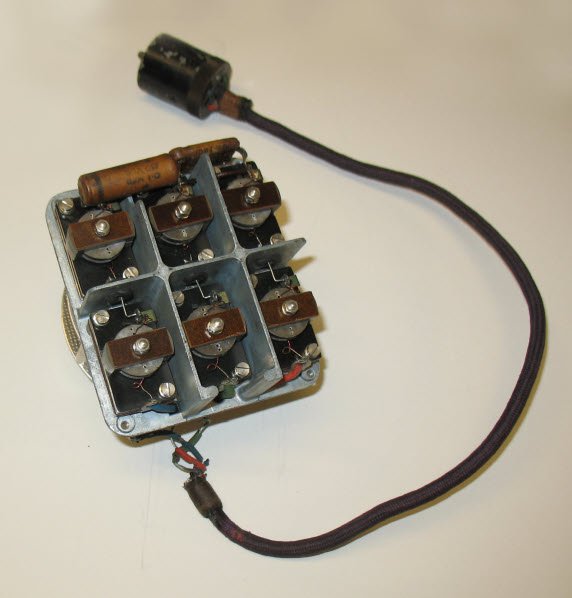

Fitted into the aeroplane behind the pilot’s seat was a Bakelite box containing a clockwork mechanism which would run for about five hours when fully wound. This was connected to an on-off switch located next to the pilot in the cockpit.

When switched on the aircraft radio would transmit a series of signals produced by electrical coils once per second for 14 seconds. The radio signal generated would then be received by the tracking station to enable the location of any particular group of aircraft to be located at any time. There is even a small heating coil inside to maintain the temperature to aid better timekeeping.

The system was normally used in two aircraft in the squadron. The clocks would be synchronised with the control tower and then when required the clock signals could be transmitted from the aircraft so that its location could be determined from the direction of the signal being received at a number of different receiving and transmitting stations. The information would then be transferred to the operation control centres so that aircraft could be directed to where they were needed to intercept the enemy.

Link to source of Spitfire image used above.

English thirty-hour longcase clocks

This post was written by David Thompson

As well as being Chairman of the AHS, I am also Curator of Horology at the British Museum. In my museum capacity recently I have been engaged in documenting a large and fascinating collection of English thirty-hour duration longcase clocks presented to the Museum by Michael Grange in November 2010. This extensive collection covers the period c.1700 to about 1840 and contains clocks from a wide variety of locations around Great Britain.

Today, these clocks still have a place in countless homes both in this country and abroad and there is no doubt that they each have a story to tell. At so many levels they reflect the tastes of those who first owned them back in the 18th century and show characteristics which are often peculiar to the locality in which they were made.

Recently, I was looking at an example by Richard Midgley of Ripponden. The stained-oak case with a forward-sliding flat-topped hood is typical of about 1740 but, unusually, there is no opening door on the hood and no mask inside to surround the dial. This is not all – this clock is eccentric in several other respects.

The five minute numeral has an embellishment in the form of an engraved flower and a further flower can be seen next to the 30 minute numeral. It seems likely that these have been engraved to mask errors.

In addition to this, the clock is pretending to be something it is not. The ringed holes near to the IX and III are not winding holes, as would be expected in an eight-day duration clock, but are simply dummies to give that impression. Keeping up with the Jones’s was clearly not an uncommon concept even in the 18th century.

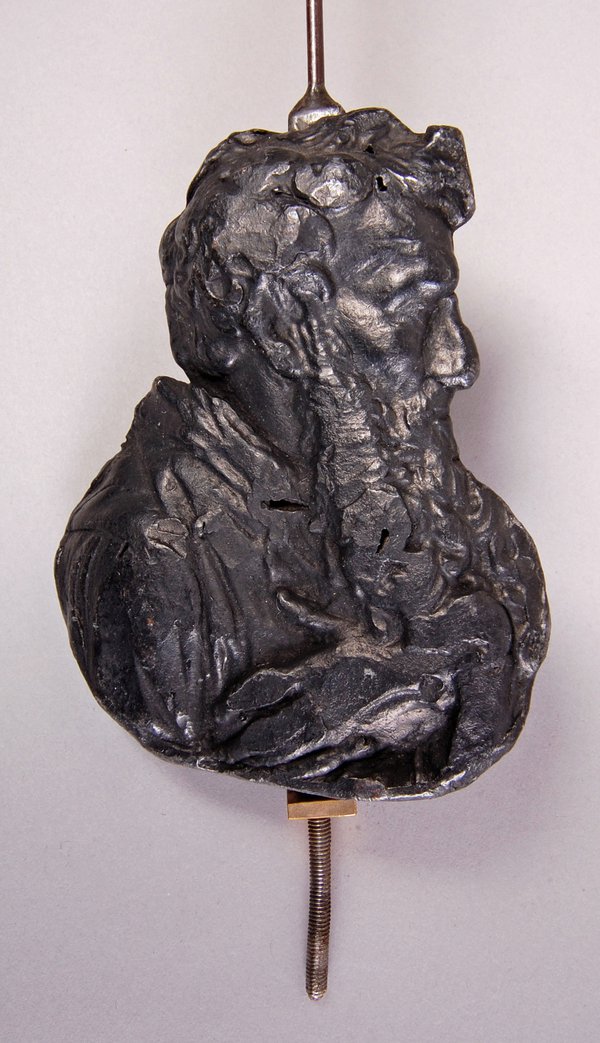

There is a final twist in the slightly eccentric nature of this clock. The pendulum bob is of a type which I have never seen before – in the form of a portrait bust. Assuming that this is the original pendulum, could this be a portrait of the maker Richard Midgley. Does it relate to the first owner? In any event it is a rare feature.

The Grange collection is a splendid addition to the collections in the British Museum and provides a unique opportunity to study and learn about the story of longcase clockmaking around the country – 'affording delightful prospects' as Gerard Hoffnung once said.

Welcome

This post was written by David Thompson

Welcome to the Antiquarian Horological Society Blog. This blog marks a new era in the activities of the society.

I should really be saying Welcome to the AHS blog. The AHS – The Story of Time is where we are now at the beginning of 2012.

There are many things to look forward to from the AHS. New books being published, a wonderful new venue – the Royal Astronomical Society, Burlington House – for our London meetings, as well as a year of lectures not only being held by our various active sections around the country, but also by the sections abroad, in Canada, Eire, the Netherlands and the United States.

The blog will include items for all those who have an interest in antiquarian horology, and those who didn’t know they had – until now. It will be about clocks and watches and the story of time in all its forms, from the earliest timekeepers.

I was once asked – 'What is it that so fascinates you about old clocks and watches?' 'Well,' I replied, 'where else will you find objects of beauty which also have a practical and sometimes vital function? What other objects tell stories about the history of technology, about the history of the people who made them and the people who owned them?'

That old clock which came from grandmother’s house and now lives in your front room – what do you know about it? You’ve known it since you were a child, but have never had much idea about how old it is.

Our society is all about knowing – or at least doing our best to know when and where clocks and watches were made and how they fit into the story of time. We look forward to items being presented on this blog which will intrigue, inform and entertain you.

Happy New Year and Welcome to the AHS Blog.

David Thompson

Chairman