The AHS Blog

Harrison decoded: towards a perfect pendulum clock

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In July 2014 the NMM hosted on one-day conference, entitled Decoding Harrison, which presented the story of around forty years of collaborative research into John Harrison’s complex and surprising pendulum clock theory.

During the conference the exciting result of a previously unannounced and unofficial test of Martin Burgess’s ‘Clock B’ at the Royal Observatory was revealed.

‘Clock B’ is one of two clocks made from modern materials, chiefly duraluminium and invar, that follow the perceived format laid out in Harrison’s convoluted text: Concerning such mechanism… the lengthy title gives the reader an accurate sense of the complexity of the book itself.

For example, footnotes occasionally run across more than one page and if that was not enough, some even have their own footnotes. In short, it is not an easy read.

The unofficial test was conducted with the clock sealed into a Perspex case, which was made tamper-proof by applying two wax impressions, kindly provided by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers and the National Physical Laboratory on 1 April, 2014, over wires threaded through the nuts and bolts that hold it shut.

On 6 January, 2015 – some 280 days after the case was sealed – Museum staff and the Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, Jonathan Betts, gathered to witness the going of the clock and initiate an official 100-day trial of its timekeeping.

Using the a radio-controlled clock that receives the MSF time signal, the accuracy of the speaking clock was confirmed and then used to determine to going of ‘Clock B’. We determined that the clock was showing UTC -1/4 second.

The clock will be observed throughout the trial using the above method as well as being continually monitored by a Microset and GPS as well as the environmental conditions inside the case (temperature, humidity and barometric pressure).

The trial is intended to prove that this clock is the most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free-air in existence. Throughout the trial I will be blogging and posting updated videos to youtube, which you can subscribe to.

To wrap up this exciting experiment we will be presenting the data collected, the current understanding of how the clock works and, indeed, why it works so well in a one-day conference at the National Maritime Museum on 18 April, 2015, which incidentally will mark the 3 year anniversary of Clock B’s stay here in Greenwich.

Details of the programme will be announced shortly.

New lease of life for a distinguished old gent

This post was written by James Nye

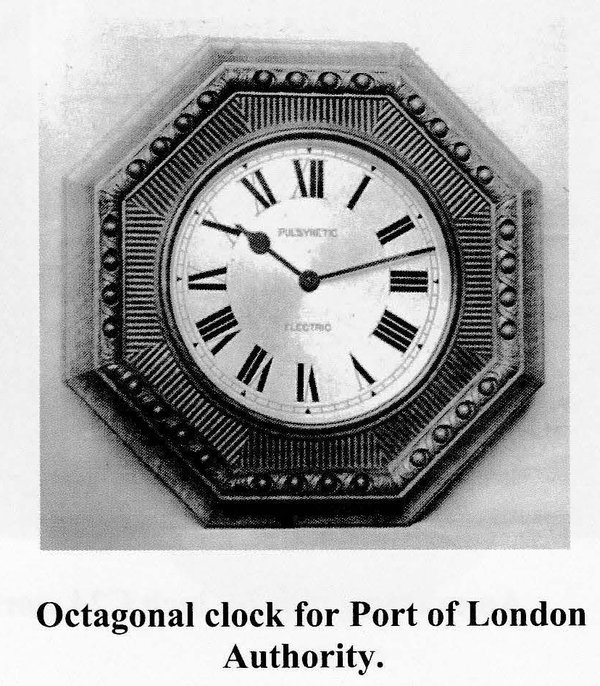

Featured in James Bond’s Skyfall in 2012, the former Port of London Authority building near London’s Tower Hill is undergoing significant change, to become luxury apartments and a hotel, badged 10 Trinity Square.

The building was opened in 1922 by Lloyd George, and its boardroom hosted a reception on 30 January 1946 in honour of the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, which had commenced earlier in the month ( The Times , 31 January 1946, p. 7).

The boardroom was recently the focus for dramatic renovation works, with original surfaces being repaired and refinished.

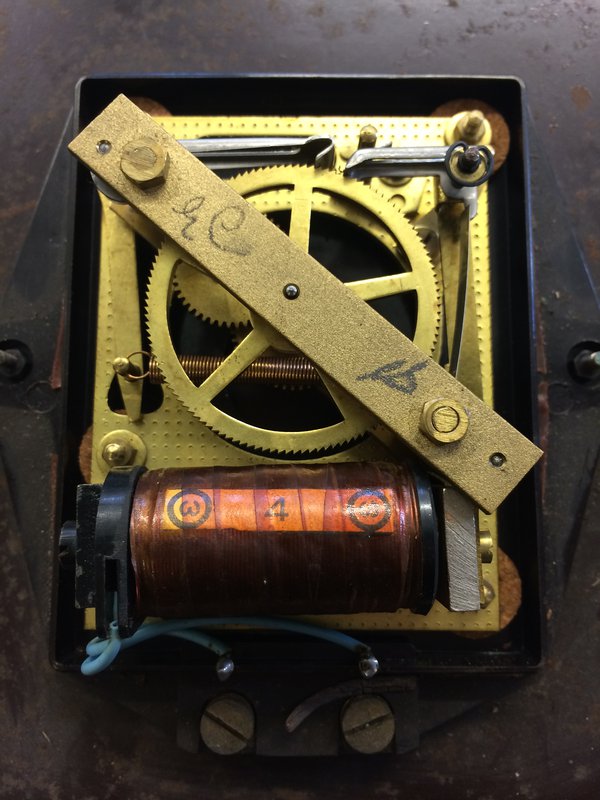

One relic from an earlier incarnation of the building to which the new owners turned their attention was the Gent Fig. C423 insertion feature clock, mounted in a panel above the balcony doorway.

This model was designed for the Festival of Britain in 1951. It is therefore clearly a later replacement of the movement first installed in 1922, but Colin Reynold’s excellent Conspectus of Clocks and Time Related Products Produced by Gent & Co Leicester (Leicester, 2011) illustrates the original pattern.

The current orphaned dial has lost the rest of its network of C7 master clock, and perhaps a hundred dials that might once have populated the building’s many rooms.

Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks was asked to attend to see what could be done to make it work.

Apart from the required servicing of the movement, the obvious solution was to provide a small self-contained master clock mechanism, quartz-controlled and battery-driven, to be hidden inside the panelling.

This parsimonious and relatively inexpensive solution has ensured the retention of a historic clock, in its original setting, and without the replacement of any parts. The old Gent lives to fight another day.

A 68 minute weight – with verisimilitude!

This post was written by Jon Colombo

At West Dean College, first year clock students make a hoop and spur wall clock from scratch. As far as practicable we use techniques available to an eighteenth-century clockmaker. This gives the deepest understanding of the mechanics, aesthetics and the way historic clocks are put together. Verisimilitude is important, but not critical. When making driving weights, students usually use brass tube, topped, tailed and filled with lead. As a former archaeologist, I wanted more authenticity.

Examining a selection of old weights showed:

- The joints do not seem to be soldered. Under a microscope, often the seam is marked by a thin copper-coloured line, likely to be loss of zinc from the brass.

- The joints are not brazed. It is common for the skin to split along the joint. Were they brazed, failure here would be very rare.

- Often the lead has shrunk away from both sides and hanger, leaving a hollow tube running down into the weight.

- The bottoms are almost always domed.

The first two suggest a butt joint. The third that the lead is stuck to the skin. It could be just the filling holding the whole thing together. Cooling shrinkage cooling would pull the skin into compression, and explain the need for domed base. The logic was convincing; time to try it.

I cut a skin and domed base of thin brass sheet, tinned and wired them tightly together. I then embedded the shell in sand and poured in lead.

Manufacture is simple, quick, economic – sheet formed on bar, butt joint filed, wired up and ready to go; hanger made from old wood screw.

The results were pleasingly close to the originals. The lead bonds firmly to the walls, heating them enough for the outside to take on a copper colour. In cooling the lead pulls the joint tight and forms the right shrinkage patterns. When I cleaned the weight, the copper colour was often left in the now very tight butt joint.

If you fancy giving it a go, or are simply curious, http://westdeanconservation.com/2014/06/05/a-68-minute-weight-with-verisimilitude/ gives a bit more detail.

War time reflections

This post was written by James Nye

The June centenary of the Archduke’s assassination is behind us, though in July 1914 no one imagined a world war breaking out a month ahead (head to the LMA for a great new exhibition).

In May, my talk at Greenwich—‘Bang on Time’—focused on 1940s clockwork devices used for delaying explosions, and it seems quite a few of my blogs dwell on bombs and destruction. Today, I reflect on some horological titbits from the Great War.

For a start, patriotism (and then conscription) emptied out light engineering and clockmaking firms of their young workers.

Of the 450 staff at Smith & Sons (MA) Ltd, floated in July 1914, nearly 10 per cent were at the Front a month later.

Silent Electric’s Herbert Bowell confirmed to the authorities in March 1917 that all his employees had signed up in 1914.

His better-known brother George, by contrast, was a munitions worker—the path for many other craftsmen.

After the ‘Shell Crisis’ of May 1915, resources poured into shell and fuze-making capacity, with the result that millions were crafted, to be fired on the battlefields of Europe. Though military demand for chronometers and timekeepers of all sorts mounted rapidly, clock and watchmakers from Clerkenwell were packed off to the north-east to work in firms such as Vickers, to manufacture fuzes.

While the factory workers and the soldiers they supplied are long gone, their products endure.

A standard artillery fuze might delay firing the main charge by up to half a minute. Precise (and expensive) fuzes had a clockwork escapement (see video) while vast numbers were simply igniferous, though even then involving a dozen or more precisely machined parts.

These remarkable engineered brass mementos regularly emerge from the soil a century later, and will still strip down.

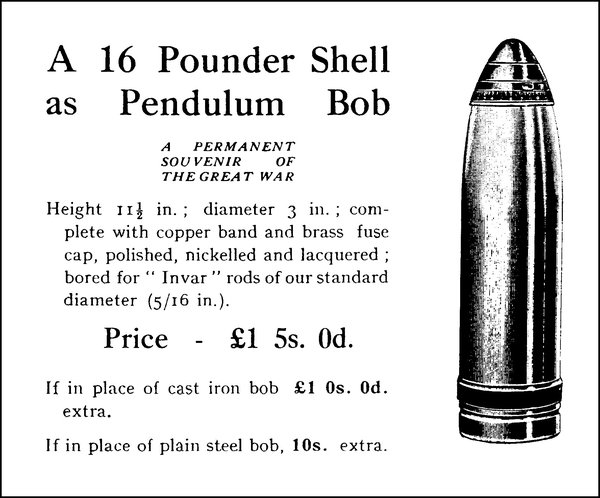

While surplus shell cases formed myriad household ephemera for years – Trench Art – another astonishing survivor was courtesy of the clock trade itself, in an idea from the irrepressible Frank Hope-Jones, who purchased 16-pounder shells (and fuzes), offering these as a pendulum bobs—a ‘souvenir’ of the Great War. What a blast!

Unreliable public clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

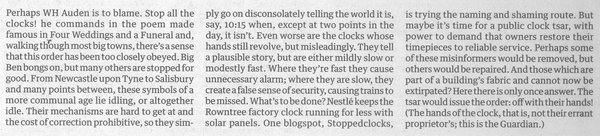

You only have to walk around in your own town to observe that of all the public clocks you pass by, only a few tell the correct time. Many show just any time, others have stopped working altogether.

Last year, a tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Guardian suggested that it was ‘time for a public clock tsar, with power to demand that owners restore their timepieces to reliable service’.

Here I learned of the existence of the blogspot Stoppedclocks, which invites us to ‘help find and fix all the stopped public clocks in Britain’. So if you have a particular gripe about a faulty clock in your area, you now know where to turn to.

There is, of course, nothing new under the sun. More than three centuries ago a correspondent to a London newspaper ventilated his gripe about the unreliability of public time-pieces.

It is quoted here, with the numbers referring to the map, as published in an article by Anthony Turner entitled ‘From sun and water to weights: public time devices from late Antiquity to the mid-seventeenth century’, published in Antiquarian Horology in March 2014.

![Details from John Roque, Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark…, 1747. The eastward route of the correspondent of the Athenian Mercury, and the nine numbered locations, from Covent Garden [1] to the Royal Exchange [9], are indicated in red (click on image to expand it)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/map-of-London2.width-600.jpg)

'I was in Covent Garden 1 when the clock struck two, when I came to Somerset-house 2 by that it wanted a quarter of two, when I came to St. Clements 3 it was half an hour past two, when I came to St. Dunstans 4 it wanted a quarter of two, by Mr. Knib’s Dyal in Fleet-street 5 it was just two, when I came to Ludgate 6 it was half an hour past one, when I came to Bow Church 7, it wanted a quarter of two, by the Dyal near Stocks Market 8 it was a quarter past two, and when I came to the Royal Exchange 9 it wanted a quarter of two: This I aver for a Truth, and desire to know how long I was walking from Covent Garden to the Royal Exchange ?'

(Quoted from The Athenian Mercury, vi no 4, query 7, 13 February 1692/93).

Changing times in Germany

This post was written by David Rooney

We call it British summer time, but the first country to advance its clocks during the summer was Germany, which inaugurated a daylight-saving scheme in April 1916.

A letter, written 100 years ago this week and found buried in a museum archive, holds an important clue as to how the idea reached the top of German government just days before the outbreak of the First World War.

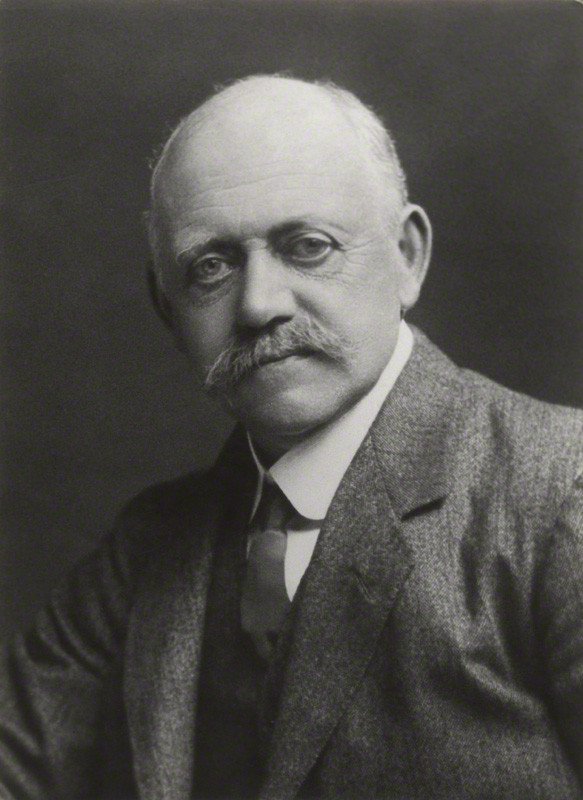

The champion of daylight-saving, British house-builder William Willett, had spent many years campaigning around the world for his time-shifting scheme to be adopted, and had become a regular correspondent with Henry von Böttinger, a prominent German chemist and industrialist who had been appointed to the Prussian House of Lords in 1909 by the German Emperor, Wilhelm II.

In 1913, von Böttinger had written to Willett to say that he was 'still pushing the Time Saving Question' and had raised the matter with the Prussian Minister of Public Works and the Association of German Chambers of Commerce.

But it was on 21 June 1914 that von Böttinger wrote again to Willett, this time with news that he was about to take the daylight-saving proposal to Germany’s highest authority.

'I have meantime taken note of your wish to have the subject laid before the German Emperor—and as His Majesty knows me personally and very well, I have at once made a written report to him and have asked him to devote his interest to the furtherance of this great object. As soon as I have another personal interview with His Majesty I shall not fail to bespeak the subject with him and thus bring the matter still closer home to him.'

Seven days later, Kaiser Wilhelm’s friend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated, and Europe began its plunging descent into war.

This was the last letter William Willett received regarding his international daylight-saving campaign, and a few months later, while on a business trip to Spain, he contracted influenza and died.

We will never know the full circumstances of Germany’s adoption of daylight saving time in 1916, but it is possible that this letter between two influential international businessmen represented the crucial turning point in Willett’s campaign—though it was a campaign he did not live to see realized.

What is certain is that technology and politics are inseparable: ideas need powerful backers, and the German Emperor in 1914 was truly one of the most powerful men in the world.

Keeping in touch with time

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

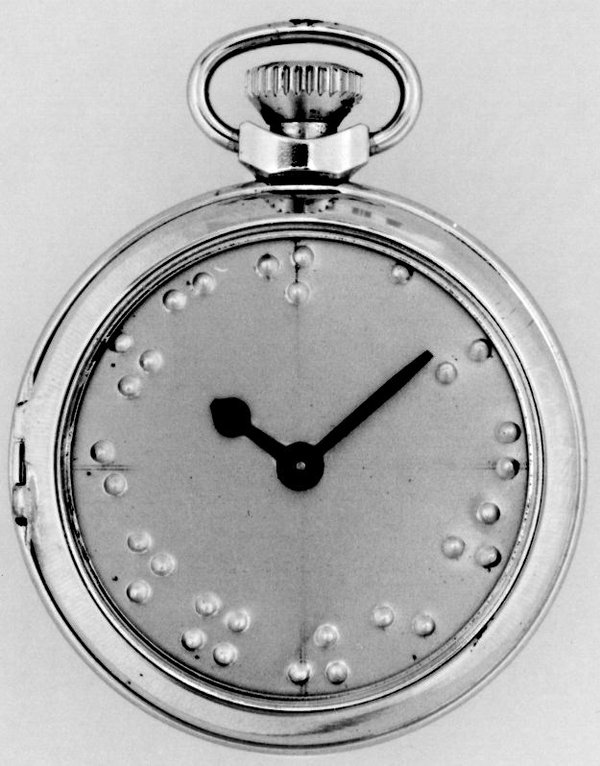

A common feature of watches and clocks of the 16th century are touch-pins. These are raised studs located at each hour position on the dial, with that at the 12 o’clock position typically being longer and sharper to provide a point of reference.

These enable the time to be read by feeling the position of the single, robust, hour hand.

This was useful as it was not possible to simply switch on a lamp to read the time at night. An added benefit might have been that the time could be read discretely under one’s robes.

This is a later variation of touch indication, known as a “montre à tact” (“touch watch”).

The exposed hand does not turn with the movement but it is moved manually, clockwise, until it stops at the right time. This is read against touch-pins that are located on the edge of the case.

These watches are also sometimes known as “blind-man’s” watches but, although they could have served as such, they were conceived as night watches.

This watch, however, was clearly designed to be used by visually impaired persons as it has Braille numerals on the dial.

Mass production of watches and clocks became established in the 19 th century and it enabled them to be affordable to the masses and, subsequently, the massive new market enabled a much greater variety to be economically viable, including this Braille watch.

This wrist-watch bears the latest incarnation of touch indication.

The time is indicated by steel ball bearings which run in tracks, positioned by magnets driven by the movement within the case – the hours around the perimeter and the minutes on the front of the watch.

The balls are easily displaced, which prevents damage to the movement, but are easily relocated with a twist of the wrist.

The watch was conceived for use by visually impaired persons, but its elegant design appeals to a far larger market. The development of this watch somewhat parallels that of the Braille watch, as it also depended on a fundamental development in technology and economics.

This watch was brought to market through internet “crowd-funding”, whereby many individuals invest a relatively small amount each to raise the total capital necessary to fund the development of a product (in this case enabled by Kickstarter). Crowd-funding can enable some exciting projects to succeed which might have been rejected by more traditional investors.

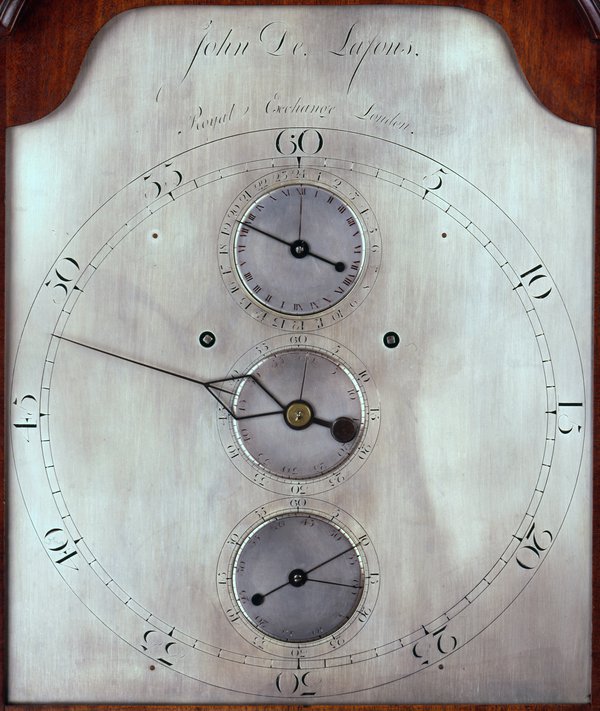

A second in one-hundred days: insanity or genius?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In 1775 John Harrison made a critical remark about Graham’s dead beat escapement, saying, of George Graham, that '…either he must be out of his Senses, or I must be so!'

Later in the same publication he stated of his own clock that '…there must be then more reason…that it shall perform to a second in 100 days…than that Mr Graham’s should perform to a second in 1.'

Keeping time consistently to within one second in 100 days was a degree of accuracy not achieved until around a century and a half later by mechanical clocks such as Shortt’s free pendulum system.

Harrison published his remarks in a vitriolic and virtually impenetrable book, the manuscript and transcriptions of which are freely accessible online.

On reading the book, which contains scattered descriptions of his method, the celebrated watchmaker Thomas Mudge, stated of Harrison that the book’s contents had '…lessened him very much in my esteem…' and that '…there are several things which he says about Mr Graham’s pallets and pendulum that are absolutely false…'.

The London Review of English and Foreign Literature described the work as 'one of the most unaccountable productions we ever met with' and went on to say that 'every page of this performance bears marks of incoherence and absurdity, little short of the symptoms of insanity'.

Harrison’s words were not taken seriously by any of his contemporaries and his radical statement about the capabilities of his pendulum clock, with its large pendulum arc, relatively light bob, and recoil grasshopper escapement, remained largely unexplored until the 20th century.

Then, in 1977, a number of horological scholars, who became known as The Harrison Research Group, began to look at his theories afresh.

Martin Burgess’ Clock B is a product of this collaborative research and represents one of the most significant historio-technical investigations in recent years. Recently, numerous experiments have been tried on the clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with exciting results.

To learn more about this intriguing project please join us for a special one-day conference on July 12 2014 at the NMM.

The AHS Annual Meeting 2014

This post was written by David Rooney

On Saturday 17 May, 120 AHS members and guests packed into the National Maritime Museum’s lecture theatre for our 2014 Annual Meeting. It was a sell-out crowd, and what a day we all enjoyed.

Those who couldn’t make it missed a couple of important announcements which I’ll pass on here in advance of them appearing in the next Antiquarian Horology .

The first announcement came from Sir Arnold Wolfendale, the 14th Astronomer Royal, who has been a tireless supporter and champion of the AHS since becoming our President over 20 years ago.

Sir Arnold, whose inspiring and lively lectures on cosmological aspects of timekeeping have been enjoyed by so many of us over the years, has decided to stand down. We wish to thank him hugely for all of his support over the years and wish him well in his ‘retirement’ from the presidency.

David Thompson then announced that Professor Lisa Jardine, the eminent historian, writer and broadcaster, has agreed to become our new President, and takes over immediately.

Lisa is teaching this term at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (home of the recent Time For Everyone symposium), and could not be present in person, but she sent her best wishes and looks forward to meeting us in person in the near future.

We are delighted and honoured to welcome Lisa to the AHS presidency.

The other major announcement of the day was the launch of the brand new AHS website. We urge you to take a look. It is the culmination of many months of patient work by a small AHS team plus our designers, Latitude, and our web developers, Blanc, and has been fully funded by a donation from council member James Nye.

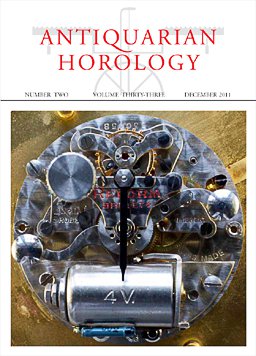

At the heart of the website is a remarkable new resource for AHS members. We have digitized the entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, and every single page we have ever published, dating back to the first issue in 1953, is now available and searchable online.

We are thrilled to bring this invaluable resource to members and wish to thank our great friends and technology partners, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in Germany, for carrying out the scanning and indexing work at an extremely preferential rate.

You can find the new website at our usual address, www.ahsoc.org, and to use the digital journal, simply log in to the members pages with the password printed on the back of your AHS membership card.

The addition of the journal archive is an extremely valuable new member benefit which must surely be worth the AHS subscription alone, so do please encourage your friends, colleagues and clients to join (don’t forget that you can join online using credit cards, debit cards or PayPal in just a few easy and secure clicks).

A tiny housekeeping note. The AHS blog on which you are reading this post has now moved to blog.ahsoc.org. The old address will still work fine, but if you subscribed to posts using an RSS feeder, we’re afraid you’ll need to re-subscribe from the new location. Sorry about that.

There’s never been a better time for reform!

This post was written by James Nye

A gauntlet has been laid down. Across Europe, thoughtful people are busy working up ingenious ideas for a competition devised over an extraordinary April weekend in southern Germany.

Each year, several dozen of the electro-horo-cognoscenti gather in Mannheim-Seckenheim for an event organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven.

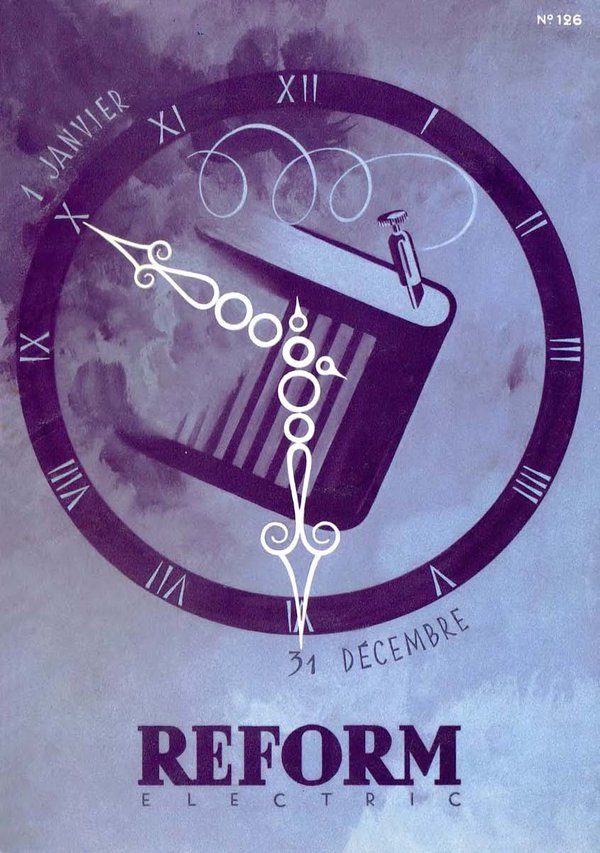

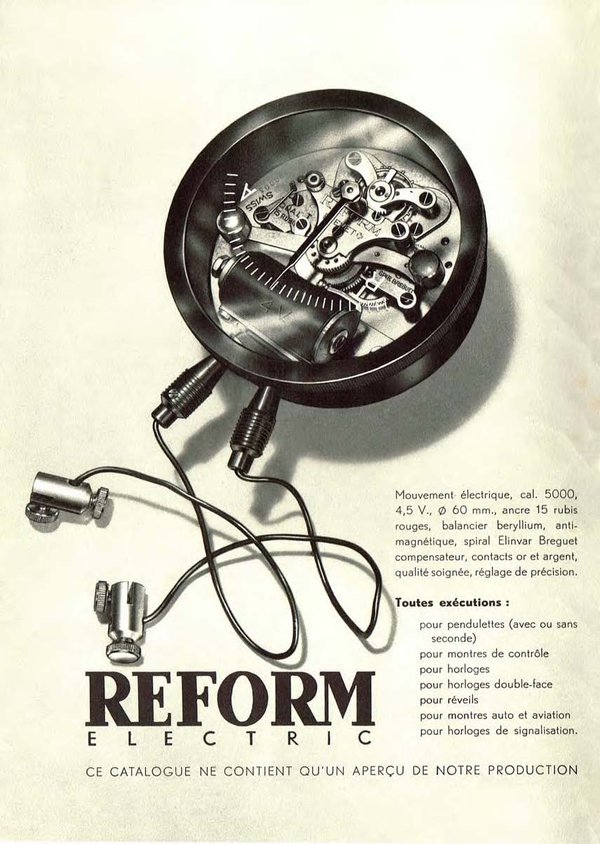

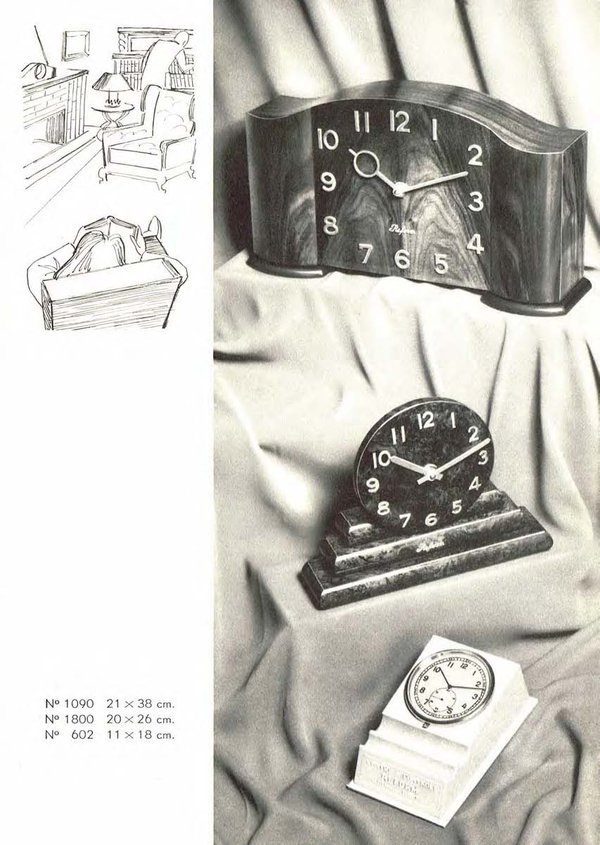

The fifteenth of these gatherings—a combination of market, lectures and much eating, drinking and good conversation—saw a new visitor who brought many interesting items, not least several hundred new-old-stock Reform movements, tissue-wrapped and boxed.

Alert readers will recall an Antiquarian Horology cover featuring a classic example of the Reform calibre 5000 movement, and a fascinating accompanying article.

As David Read comments, these Schild movements are ‘without doubt the best known and most commercially successful of all the many varieties of electrically-rewound clock movements’ from the 1920s onwards. The calibre 5000 is a lovely object, jewelled, with damascened plates, and micrometer regulation.

Nye’s theorem proposes that hi=as*bc/ebw where hi stands for horological inventiveness, as represents afternoon hours of sunshine, bc denotes beers consumed and ebw stands for evening bottles of wine.

With a lively group, talk over two sunny days and late evenings turned to possible creative uses for virgin Reform movements.

Given their looks, the mechanism must remain visible, but the motion work is to the (unremarkable) reverse. This led to discussions of projection clocks, or elaborate gearing to present time in the same plane as the movement, but to one side.

There was even intriguing talk of a large scale tourbillon. More detail than this presently remains closely held, but a competition to determine the best use was announced, to be decided in Mannheim in April 2015.

Reform is the order of the day.

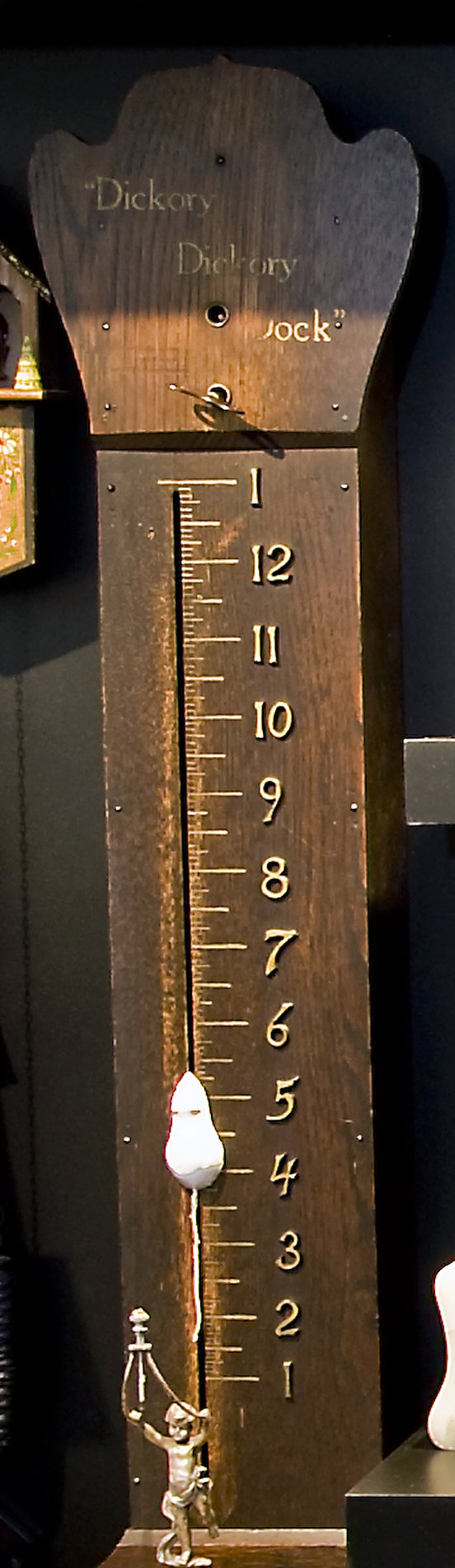

Of mice and clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In his most recent blog, Oliver Cooke discussed watches and clocks without hands as indicators.

Another example is the Mouse Clock, in which a mouse making its way up against a wooden board serves as time indicator. Its designer was inspired by the well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickere, Dickere Dock

A Mouse ran up the Clock,

The Clock Struck One,

The Mouse fell down,

And Hickere Dickere Dock.

The rhyme comes in various versions; this is the oldest, published in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s_Pretty_Song_Book.

Could it be based on a real event: a mouse hiding inside a longcase clock, panicking when it struck?

In the literature I find only other explanations. One authority suggests it may be an onomatoplasm – an attempt to capture, in words, a sound; in this case, the sound of a ticking clock. Another relates it to the shepherds of Westmorland who once used ‘Hevera’ for ‘eight’, ‘Devera’ for ‘nine’ and ‘Dick’ for ‘ten’ when counting their flock.

Be that as it may, just over a century ago it inspired an American businessman, who was also an avid clock collector, named Elmer Ellsworth Dungan, to develop the Mouse Clock.

He initially just created one for his daughter, who loved the nursery rhyme, but then decided to take them into production. He took out patents and various models were manufactured.

They are nowadays prized by novelty clock collectors, so much so that we are warned to beware of reproductions, especially for what one dealer calls ‘Chinese knockoffs’.

Details, including several images of the mechanism, and a link to an animated photo of the clock in operation, can be found on these American websites: Antique Clock Guy and Fontaine’s Auction Gallery.

In 1966 the NAWCC published a booklet by Charles Terwilliger, Elmer Ellsworth Dungan and the Dickory, Dickory Dock Clock; there is a copy in the AHS Library at the Guildhall.

And speaking of mice and clocks, how about having some fun with the (grand)children with this on-line clock reading game. Read the time correctly and the mouse runs up safely to the cheese in the clock. Read it wrong and the cat gets the mouse.

British Pathé films on YouTube

This post was written by David Rooney

In the latest in what seems to have become a short series on easy-access digital resources, I bring news that British Pathé has released its entire historical newsreel archive of 85,000 films onto YouTube, the video-sharing website.

British Pathé has long allowed people to see its historical newsreel films on its own website, and the release to YouTube doesn’t bring any change to the company’s copyright policy. But the findability of these often remarkable films will now have greatly increased, which can only be a good thing.

I have used British Pathé films in my historical research and my professional work curating museum exhibitions for years now, and it is therefore like meeting old friends to watch films on the YouTube channel such as The Golden Voice, Time Please and Standard Time.

For those with wider interests, I’ve also been moved seeing Comet Inquiry again, which appeared in the Science Museum’s recent award-winning Alan Turing exhibition. One of the AHS’s founder members, Alfred Basil Brooks, together with his wife, were killed in this tragic air crash which occurred just months after the founding of the society.

I think this film archive is strong in two ways beyond its sheer breadth.

Firstly, it helps to put technological objects and ideas into social and political context, which is crucial in understanding why people make, modify, use and choose things. Objects never emerge fully-formed in a contextual vacuum.

The second strength of the films is the technical understanding they can offer those studying particular technologies. There’s nothing like the moving image to bring dynamic objects to life.

So there we are. Another great digital archive of work made even easier to use. And along those lines, AHS members should watch out for an important announcement in the next few weeks. We’ve been working on something pretty special and we’re about to be able to share it with you…

You can find the British Pathé channel at https://www.youtube.com/user/britishpathe. Search by clicking the little magnifying glass symbol in the middle of the page underneath the header image.

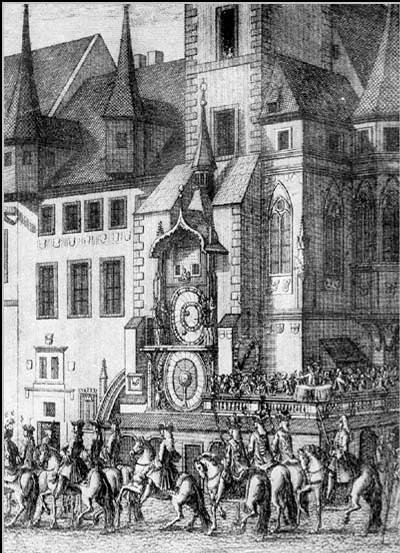

Time in Old Bohemia

This post was written by David Thompson

Many thousands of people today have stood amazed in front of the Astronomical Clock in the Old Town Hall Square in Prague, but I wonder just how many have managed to make sense of the dial. In modern times, perhaps it makes little sense.

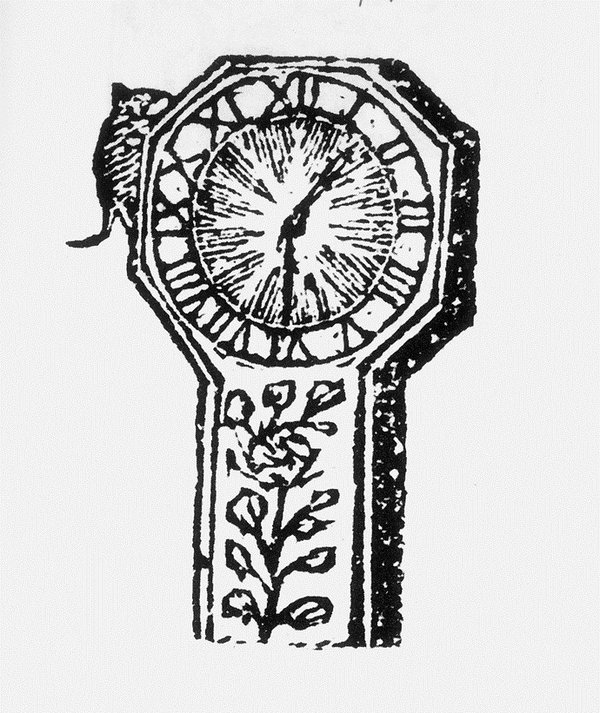

The clock was made by Jan Šindel in about 1410, and from as early as the 15th century, the clock had a 24 hour dial which showed the so-called Bohemian Hours, a system in which the day began and ended at sunset.

This means, of course, that the 24-hour ring around the outside had to be adjusted periodically so that the 24th hour coincided with sunset.

In the early part of the clock’s life this was done manually, but later an automatic mechanism was installed to adjust the position of the ring. In medieval Prague, a knowledge of how long it was to sunset and the imposition of curfews in the city was useful knowledge. For instance – a simple glance at the dial indicating 19 hours tells you straight away that it is five hours to go before sunset.

As well as telling the time, the dial also has moving sun and moving effigies of the sun and moon, showing where in the zodiac they lie throughout the year. Useful astrological information.

The ecliptic circle with the zodiac signs and the sun and moon effigies rotate together once per day, but gradually over the course of the year, the sun and moon effigies with make a complete circle of the zodiac.

All this is achieved by some sophisticated gearing located behind the dial and driven by the clock mechanism in the tower. With the horizon circle with shaded buff areas, the periods of Aurora and Crepuscular, dawn and dusk are also shown,

Today, the clock is controlled by a more modern ‘regulator clock made by Romuald Bozek in the 1860s, but for the most part, the clock mechanism is still that which has been in existence from the beginning of its history.

Looking at the illustration here, you will see that the time is just a few minutes past 13 hours. On the fixed chapter circle the time is shown just before IX o’clock in the morning and hour 24 is just before 8 o’clock in the evening – correct for a July date. The sun is in Leo and the moon is in Aries.

So next time you stand in front of this amazing clock, you can really show off by knowing how to read the dial.

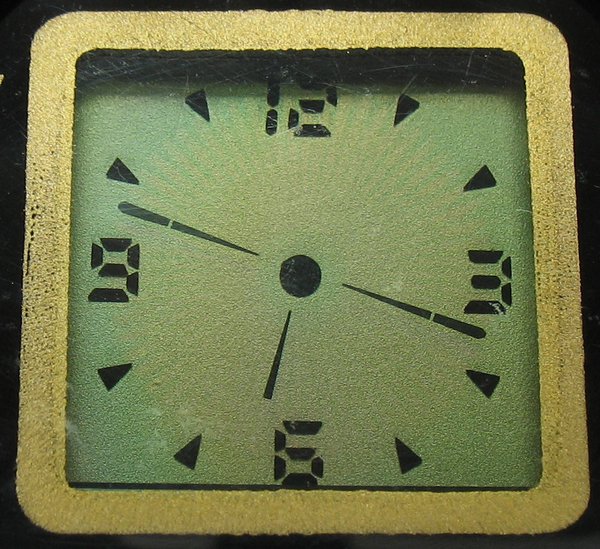

Look no hands!

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have looked at single-handed dials, on the other hand we have looked at some more unusual forms of indicator. Here we will look at indicators with no hands at all.

This watch has a display with digits formed of light emitting diode (LED) segments, seven for each numeral.

LED watches were first introduced in 1970 by the Hamilton Watch Company and were soon followed by liquid crystal display (LCD) watches. LED and LCD were by no means the first technology to enable digital displays however.

Before these examples existed the 'wandering hour' dial, something of a mash-up of digital and analogue time indication.

The hour numeral wanders, from the left-hand position (as viewed), up-and-over the semicircular aperture during the course of an hour. As the current hour ends and disappears behind the dial plate, the next hour numeral appears on the left.

We see 12:14 indicated on the illustrated example.

The system was invented in the 1650s by the brothers Tomasso and Matteo Campani from San Felice in Umbria, as a means to enable the time to be read at night (the numerals are pierced, allowing the light of an oil lamp to pass through from behind). This was very useful in the days before instant electrical lighting.

The wandering hour dial was also, occasionally, used on watches in the late 17th century, (but an oil lamp was not fitted in these!)

Finally, this watch also blurs the distinction between analogue and digital.

It has an LCD but, instead of digits, it has radial segments representing hands. This, however, requires 120 segments instead of the 42 needed to make up a standard six-digit digital display.

Together with the corresponding electronics needed to drive each segment, this means that these “LCA” watches cannot be made as cheaply as their digital counterparts. Perhaps for this reason they have never been popular, but they must have an adequate, if small, number of fans as they seem to have always (just) remained in continous production by one manufacturer or another since the 1970s.

I wonder how many of their fans, like I, appreciate them mostly for the futility of over-engineering, to achieve a result with LCD that is much more easily and better obtained with physical hands!

Clock world full of cranks?

This post was written by James Nye

Things turn up. Back in 2006, when David Rooney and I were researching the Standard Time Company (STC), we planned a lecture at the Guildhall library.

The only surviving early clock we knew of had spent its life at the Royal Observatory—but out of the blue, days before the event, a Lund-synchronised dial clock turned up.

In the following eight years, that was it—nothing else—and then suddenly, through the kind agency of Keith Scobie-Youngs, The Clockworks acquired a wonderful addition a few weeks ago, in the form of an outsized fusée gallery movement, fitted with a massive Lund synchroniser.

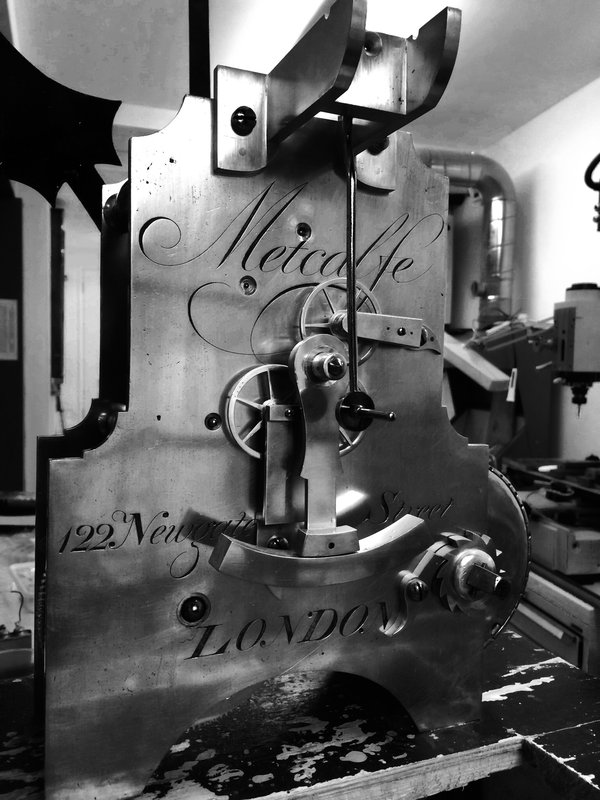

The movement is by Thwaites, from the early nineteenth century, and signed elaborately by Metcalfe of 122 Newgate Street, London.

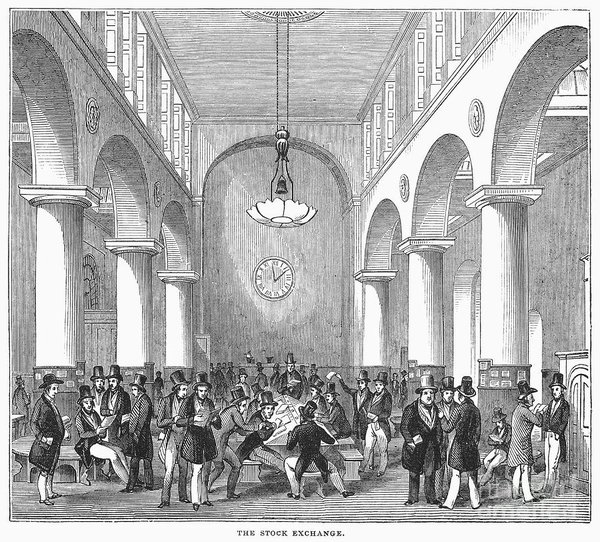

When STC went public in 1886, it listed its clients in the prospectus, and the very institution on which it was being floated appeared second in the list.

The accurate timing of bargains made by the jobbers on the London Stock Exchange was an important matter, and ‘the House’ was an early adopter of the new technology that provided hourly synchronisation of its clocks.

Remarkably, our new addition was one of probably several STC-synchronised clocks that populated ’Change, where it seems to have served for some time.

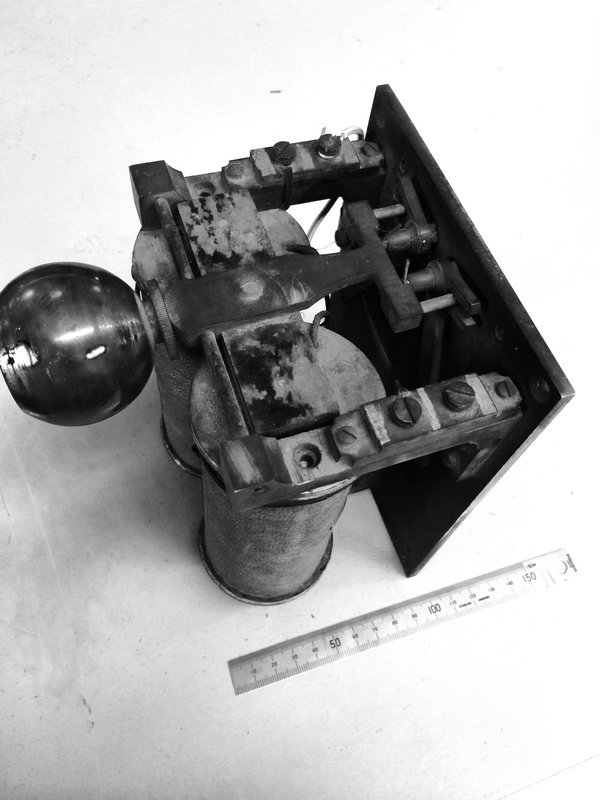

Each hour, a signal would travel from STC’s offices on Queen Victoria Street around a series of looped networks, energising the coils of the synchronisers. These were the ‘set-top boxes’ of their day, added perhaps many decades after a clock was first made—as was clearly the case with this clock.

The Stock Exchange synchroniser is particularly large, operating two small fingers that project through the dial, to correct the minute hand each hour. The long use of the device is evidenced by the deeply indented witness marks in the tab on the back of the hand, caught by the synchroniser.

.

Overall the movement seems rather outsized for the scale of the dial it ended up supporting—the large counterweight is much more than a match for the 15-inch minute hand.

Sometimes, it’s very hard for us to trace the environs in which our clocks spent their time—and to deduce whose lives they counted out. Thankfully in the case of this remarkable STC clock, there’s an old crank that can tell us a story or two.

Stopping the clock after death

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In a previous post I included an opera scene, in which a woman mentions (sings!) that at times she stops all the clocks in her house. She dreads getting old and wants time to stand still.

One reader told me this reminded him of a poem by W.A. Auden which begins:

'Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

'Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

'Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

'Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.'

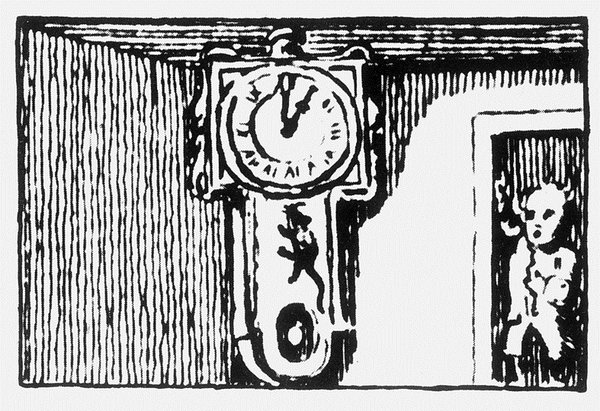

But here the motive for stopping the clocks is different. Someone has died, and stopping the clocks in the house of the deceased, silencing them, is an old tradition, similar to closing the blinds or curtains and covering the mirrors. The clock would be set going again after the funeral.

Some people believe stopping the clock was to mark the exact time the loved one had died. The subject was discussed here by members of the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in America.

The French film Jean de Florette, set in the Provence between the wars, contains such a clock-stopping scene. The film is made after a novel by Marcel Pagnol, from which the following quotes are taken.

Jean, an outsider, inherits a house with surrounding land and hopes to make a living there. But two locals, who covet his land, secretly block a source, cutting off his vital water supply.

In despair, Jean uses dynamite to create a well, but he dies as a result of the explosion (chapter 37). The doctor, taking his pulse, 'listened for a long time in a profound silence emphasized by the ticking of the grandfather clock', but the man had died.

Then one of the two devious locals, who was in the room, 'crossed himself, walked around the funeral table on tiptoe, and stopped the pendulum of the grandfather clock with the tip of his finger'.

He then tells his comrade in arms 'Papet, I have just stopped the grandfather clock in Monsieur Jean’s house' – a way of saying: he is dead.

The three stills reproduced here are from that scene, which you can see in this short clip.

The clock is a typical Comtoise grandfather clock with a big flower pendulum.

100,000 more free images

This post was written by David Rooney

When I got an email from the Wellcome Trust which began, ‘we have some very important news to announce’, it certainly got my attention.

And they were right: it is very important news indeed, and I’m delighted to share it.

In my last post I talked about the recent release of a million images by the British Library. Already I’ve heard from colleagues and friends who say they have found new evidence amidst its vast collections that is crucial to support their research.

The news from the Wellcome Trust is the same. As of January this year:

'All historical images that are out of copyright and held by Wellcome Images are being made freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This means that they can be used and manipulated freely, for commercial or personal purposes, so long as the original source is acknowledged.'

You can download high-resolution files directly from their website. There are 100,000 images dating from as early as 1000 BCE. You can even get advice directly from Wellcome’s team of researchers, should you be having trouble finding what you need.

Like many in the AHS, I’m interested not only in clocks and watches themselves, but how horological machinery gets embedded in other technologies. So I searched for ‘clockwork’ and, rather than showing you the clockwork trephine (not safe for suppertime), here’s a clockwork picture of an itinerant dentist performing an extraction in the early 19th century. Ouch.

Whether you’re into automata like this, or medical technology, or astrology or philosophy or geology or anything else related to stories of time and its material culture, you’re sure to find something here to delight.

As I said last time, image banks such as this are invaluable treasure troves of historical evidence for researchers, whatever your subject. Serendipitous browsing leads to new leads and new ideas.

Huge thanks to Catherine Draycott and others at the Wellcome Trust (as well as the British Library) for making such a bold and generous decision to open this to everyone.

The Battle of the Three Emperors – or the Battle of the Three Dates

This post was written by David Thompson

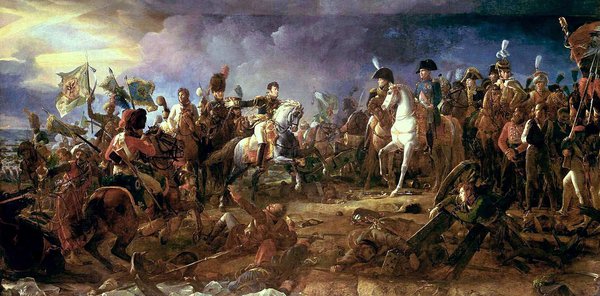

I was recently reading Dušan Uhlír’s book The Battle of the Three Emperors and I came across an intriguing fact about the battle of Austerlitz which took place on the 2nd December 1805 between the armies of Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire Empire and Tsar Alexander I of Russia against their invading enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte.

In Uhlír’s fascinating account of one of the most famous battles of the Napoleonic campaign, excepting Waterloo of course, he points out that the battle took place on a different day for each of the three armies.

For Francis II, the date was 2nd December 1805, for Alexander and the Russian army the date was 20th November and for Napoleon, Bonaparte it was 11th Frimaire year XIV.

Francis and his army were using the Gregorian calendar introduced in 1582, although it was not universally adopted throughout Europe – indeed, England didn’t change until 1752. Alexander was still using the old Julian calendar – the Russians did not change to the Gregorian calendar until 1918. Napoleon was using the French Revolutionary Calendar, introduced in 1793, but back-dated to September 1792 to mark the beginning of the new republic and each successive year numbered from then on.

It must have caused some confusion for the Austrians and the Russians when agreeing a date to face up to Napoleon and the French would have had to convert the traditional dates into their new scheme.

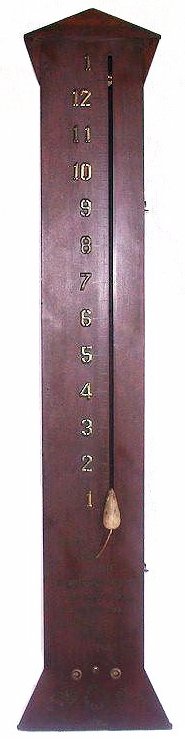

…on the other hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have simple, easy to use, single-handed dials. On the other hand, some dials are not so straightforward.

This clock has 'fly-back' or 'retrograde' hands. The hands proceed clockwise as usual but when they reach the end of the scale, each will spring back and then immediately resume its count.

This design allows the dial to have twice the diameter of a circular dial within a given height. This, together with the semi-circular form, makes these clocks suitable for positioning over doorways and they were sometimes integrated within wall panelling.

Fly-back hands are still a popular feature in watches, although these are usually (but not always) the preserve of high-end watches.

The dial of this regulator (that I have mentioned before for its escapement) has the typical features which facilitate the use of these clocks in observatories and laboratories. All hands are positioned on their own centres for disambiguation. The hours are relegated to a small subsidiary dial and only the minutes have a large hand, for accurate observations.

Less typically, however, this regulator indicates two different systems of time using only one set of hands.

It shows mean sidereal time against the numerals on the main dial plate and mean solar time against the small discs. A mean sidereal day is 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds, i.e. it is about 4 minutes shorter than the 24 hour mean solar day. The discs rotate slightly faster than the hands so that after each day they have accrued the 4 minutes difference. This system is called a differential dial.

Having a clock show both sidereal and solar time might have been a convenience, but a respectable observatory might well be expected to have had separate regulators for providing the required times and so it is possible that this design may have been conceived rather for the use of the (wealthy) amateur.

This watch has not just hands, but arms and fingers too! It is a type of watch known as “bras en-l’air”, which translates as “hands in the air” (and certainly not “bras in the air” – which might apply another aspect of horology altogether). When the pendant is pushed the soldier raises his arms, holding pistols to point at minutes (left) and hours (right).

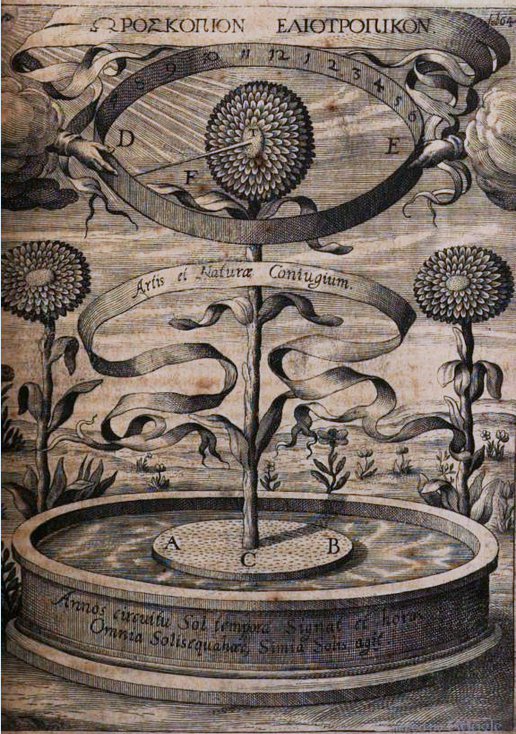

An experiment in ‘florology’

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

Recently, I have been looking at the role of timekeepers in the history of science and whilst reading around the pre-pendulum era, happened upon a blog-worthy experiment conducted by Athanasius Kircher (1601/2-80).

Kircher, a German Jesuit polymath, applied the then known phenomenon of heliotropism as a method of timekeeping.

He thought that the daily motion of sunflowers as they followed the Sun was caused by magnetic influence and thus inferred that they could be usefully used as a clock. As can be seen in his magnificent illustration, Kircher planted the sunflower in a cork pot and floated it on water, providing a frictionless pivot, and inserted a pointer through the flower to indicate time against the annular chapter.

Kircher noted that his clock was disturbed by the slightest of breezes and, when kept away from sunlight, it withered and its motion slowed. This, however, did not end the experiment. He tells us that he had the good fortune of meeting an Arab trader who happened to have amongst his aromatic wares a substance with similar horological properties to the sunflower.

The deal was struck and Kircher parted with his sundial signet ring for the horological stuff.

It has to be said that this episode is possibly a theatrical device to colour the account and introduce the use of sunflower seeds and root instead of the plant itself, but worth repeating – even if it’s just an excuse to show a beautiful horizontal sundial ring!

Today, we know that this diurnal motion is caused by sunlight and so Kircher’s clock could never have worked in the way intended, but one cannot help admire his ingenuity in applying a mystery of the physical world to tell the time. M. Becker’s 2011 time lapse movie shows that it is possible to use a flower as a twenty-four hour clock, but only in summertime at a latitude close to the north or south pole.