The AHS Blog

The engineer’s chronometer: William Wilson and the Adler

This post was written by Allan C. Purcell

Last Summer I bought on eBay this fusee chain driven watch with detent escapement, dia 50mm, hallmarked Chester 1858, signed on the movement ‘William Benton of Liverpool, No. 5115’, and on the dial ‘Chronometer watch by William Benton 148 Park Road Liverpool’.

In the description of the watch, the seller had written ‘Opening below to reveal a highly decorated dust cover “Stephenson’s Rocket, Steam Train”, and clean fully working highly decorated “Steam Paddle Ship”.’

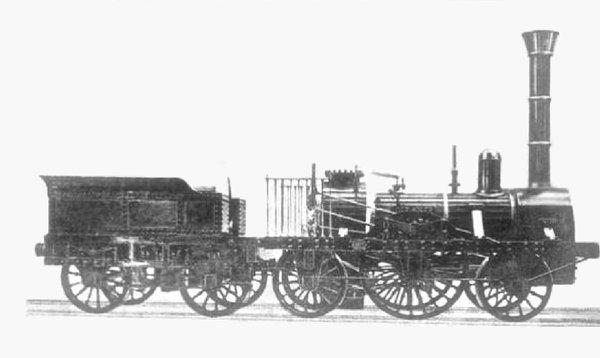

What the seller failed to point out is that the watch is inscribed on the dustcap ‘WILLM WILSON / LIVERPOOL / AD 1859’. It is my belief that this was the English engineer William Wilson (1809-1862), and that the locomotive illustrated on the watch is not the Rocket but the Adler (German for: Eagle), the first locomotive successfully used commercially for the rail transport of passengers and goods in Germany.

In 1835, George & Robert Stephenson in Newcastle were contracted by the Bavarian Ludwig railway company to build an engine for their first railway to run from Nuremberg to Furth. They sent the new locomotive packed in boxes, and their engineer William Wilson was contracted to rebuild it there. The train was a huge success and Wilson stayed with the Ludwig railway company for another twenty-five years, driving the train in all weathers. In 1859, William was covered in glory by the German railway company. In 1862 he died and was buried in Nuremberg, where his descendants are still living.

While Stephenson’s Rocket has only four wheels, the Adler had six wheels (wheel arrangement 2-2-2 in Whyte notation or 1A1 in UIC classification). The engraving on the watch shows a locomotive with six wheels. The image of the ship engraved on the watch may refer to the steamboat Hercules which in September 1835 had been used to transport the boxes containing the locomotive from Rotterdam on the Rhine to Cologne.

When in September last year I went to Nuremberg for the Ward Francillon Time Symposium, I arranged an appointment with Stefan Ebenfeld, the director of artefacts and library at the Museum of the German Railway (Deutsche Bahn Museum) in Nuremberg. It turned out that the museum had no personal artefacts of Wilson’s, and we agreed that the museum would buy the watch from me for the price I paid for it.

For anyone interested in more details, there are entries on William Wilson and the Adler on Wikipedia.

Put down your pens: the Oxford Examinations School clocks

This post was written by Johan ten Hoeve

Located on the High Street, in the heart of Oxford, the Oxford Examinations School was built between 1876 and 1882 and made the reputation of its architect, Thomas Jackson, who incorporated materials from old buildings to construct the school. Among them, Christopher Wren’s pulpit from the Divinity School forms the Examiners throne in the North School, and many now regard the building to be Jackson’s masterpiece.

In 1883 Charles Shepherd (Jr) installed a master clock and slave system with 19 slaves. This was replaced with an expanded Gents master system, with 28 slave dials, in 1959. The current dials, which are some 30 inches across, are replacement dials, having possibly been installed along with the Gents system.

Most of the original wooden housings of the slave clocks are still fitted with the old Shepherd terminals which connected the slave clock to the system. This is the only remaining evidence that there was once was a Shepherd clock system. However, the original Shepherd master and a slave clock are still around, and can now be found in the reserve collection of the History of Science Museum, Oxford.

The slave unit is described thus: “Slave unit to the Shepherd electric master clock (78037), the mechanism closely resembling that of the master. The slave unit receives the impulse every two seconds and moves the hands of the dial. The unit has two hands but no dial. Mounted on wooden board, with unfitted Perspex cover”.

The Gents slave system still operates in the Examinations School even though Gents ceased the clock side of their business in 1999 and terminated the contract. The 28 slave dials are divided up into three sub circuits; one C73 and two C74 relay units, with a power supply, trickle charger and battery back-up.

At present, the whole system, (master and all slave clocks) is undergoing a major overhaul and service.

Was there high-quality, wholesale, clock movement manufacture in seventeenth-century London?

This post was written by James Nye

There is a fascinating article in the latest edition of Antiquarian Horology, just starting to arrive through people’s letterboxes, setting out a remarkable research question which cries out for some crowdsourcing of data—hence this blog post. For those who don’t receive a physical journal, the editor has conveniently made it the sample article for this quarter. You can download it here.

Put simply, it is suggested a range of prominent makers (or perhaps retailers) bought in largely finished movements from a single source, and arranged for their casing/signature/final finishing.

This is clearly a very well-understood practice in the watch world from a relatively early date, and was certainly common practice in the clock world later on. For example, Thwaites produced movements for a wide range of other clockmakers and clockmaking firms, and on a large scale.

The question remains, how early did this standard practice emerge, and is there sufficient physical evidence to allow us to draw firm conclusions?

The key element is that Jon’s piece is a call to arms! More data is needed. And it is not difficult to look for it. This is a massively worthwhile project to support, and whatever the outcome, if you can supply data you can play a part in improving our understanding of clockmaking practice in London in the period 1660–1720. Please do get involved!

The unexpected visitor

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Almost exactly ten years ago I had John Harrison’s magnificent first marine timekeeper H1 in my workshop at the Royal Observatory. It was being dismantled for study, cataloguing and conservation for the new chronometer catalogue.

I had a film crew with me making a documentary, and they were becoming exasperated at constant interruptions to the filming. Finally another telephone call – a man was outside, asking if he could see me. Embarrassed, I assured the film team I would politely ask him to come back another time, but explained they had to come with me as I couldn’t leave them alone with H1.

Outside, the man apologised for arriving without warning and that he could come back if necessary. He introduced himself, offering his hand and just saying softly “Neil Armstrong”.

One of the film crew laughed and remarked 'Ha! I bet with a name like that you get lots of requests for autographs!' to which the unassuming gent simply replied: 'I’m afraid I don’t do autographs'.

It was at that point that we collectively realised that we were indeed in the presence of history. Suffice to say, all anxieties about filming schedules melted away and we all returned to the workshop (but with film cameras firmly switched off!)

Armstrong had long been a Harrison fan and he and his golfing friend Jim, hearing on the grapevine about the H1 research, had taken a detour from a sporting trip to Scotland, to make a pilgrimage to Greenwich.

For a wonderful hour or so we discussed Harrison and his first pioneering longitude timekeeper and it was clear Armstrong’s reputation was correct – reserved, yet of great intelligence and hugely well-informed; in short, a thoroughly nice man and not at all the showman one imagines when thinking of lunar astronauts.

I always asked visitors to sign my Visitors Book, but understood when Armstrong explained 'if you don’t mind, I’ll do it in capitals'.

Hearing that Harrison’s second prototype timekeeper, H2, would be next for research in the coming year, Armstrong returned and I spent a little more time with him, getting to know him a little better and was privileged to learn more of the Apollo 11 mission, from the horse’s mouth, as it were.

As he and Jim left on that occasion I asked Jim to sign my book again, and as they got back into their car, Jim whispered to me 'I think you’ll find Neil signed properly this time too'.

And indeed he had, something I shall always treasure.

Star of the show

This post was written by James Nye

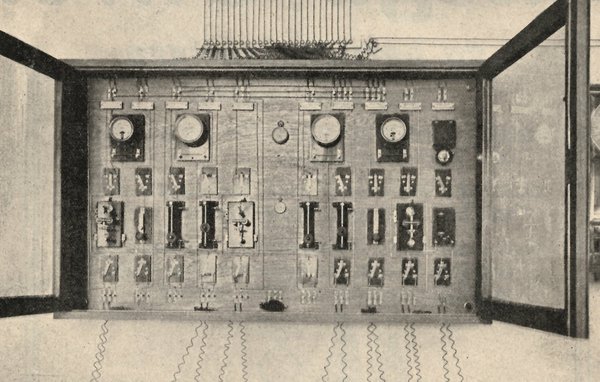

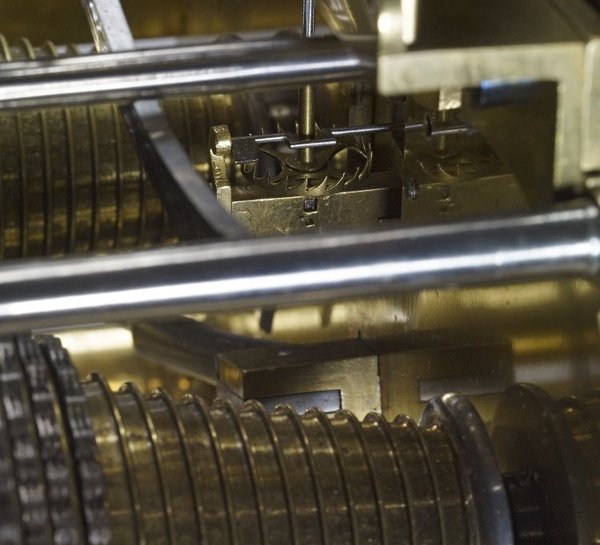

At the Mannheim electric clock fair, now in its twentieth year, one unusual item usually attracts a lot attention.

This year (2019) was no exception. The images show an early form of German ‘treppenhausautomat’, loosely a ‘staircase lighting timer’. Lighting, and therefore electricity consumption, has always been expensive.

An intriguing question, worthy of some serious research, is the economic justification for the complicated (and also expensive) electro-mechanical devices used (late 19th/early20th C) to reduce consumption.

In large houses, or multiple-occupancy blocks, it’s always made sense to add press-button switches to control stairwell lighting—the lamps remaining lit for a set period before being switched off.

Modern switches incorporate integrated circuits, but for a long-time such devices used a pendulum clock as the timebase.

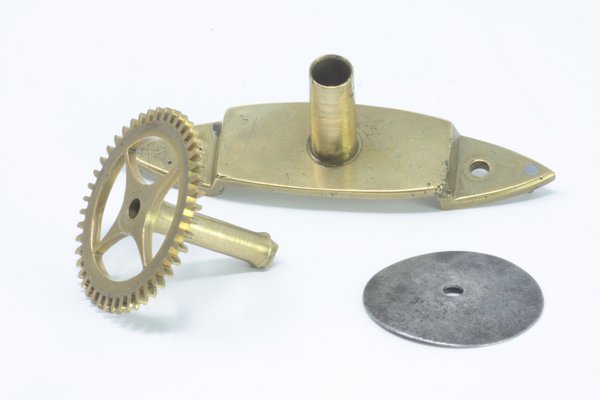

The object here dates to c.1905, and was sold by Paul Firchow Nachfolger, from 3 Belle-Alliance-Strasse in Berlin. The clock mechanism is a standard volume production element, unsigned, and perhaps from Lenzkirch.

The hands are arranged to carry an adjustable set of contacts which will make a circuit, naturally for night hours, but with the capacity to set the operating hours (accommodating seasonal variations).

Assuming it is night (dial circuit closed), pressing a push-button in the stairwell will activate the motor below the clock, which in turn will revolve the drum.The drum has brass (conductive) sides, embraced by brass slide contacts.

The drum has a narrowed section, and when this arrives between the (wider) contacts, the circuit is broken.

The cycle lasts around three minutes.

The top panel shows ceramic entry ports for various cables: knöpfe (push-buttons), power, lampen (lamps), and two set of widerstand (resistance). The machine will switch 110V and up to 18 amps, so a significant load is possible.

The clock is a forerunner of more typical, volume-produced ‘black boxes’, but its complex form (and by inference its high cost) is a strong signifier of the importance placed upon saving money and controlling power use.

The typography of revival watches

This post was written by Mat Craddock

Until recently, there had been little research carried out on the typography of wristwatch dials. However, over the past decade, the increased interest in collectable vintage wristwatches appears to have sparked the interest of brands and collectors alike.

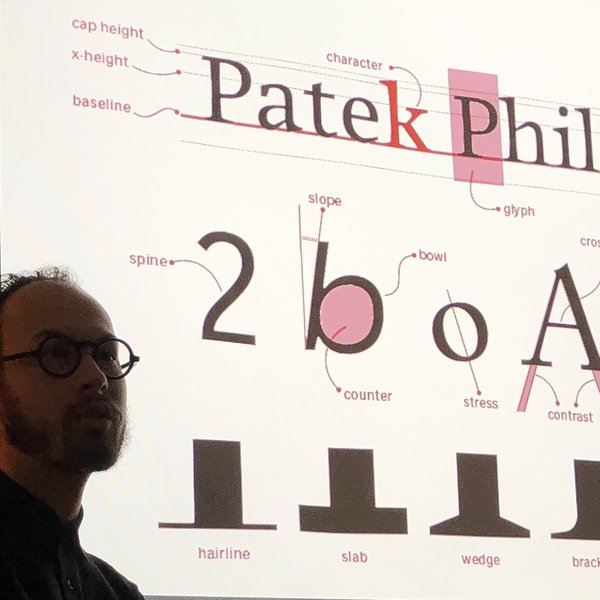

While wristwatch collectors’ focus has largely been on the variations in logo, layout and content of vintage wristwatch dials, interdisciplinary designer Lee Yuen-Rapati has taken a critical look at the typefaces used, and typographic decisions made, by watchmakers.

His Masters dissertation, titled ‘Motivating Factors In The Trends Of Horological Typography,’ formed the basis of an AHS Wristwatch Group talk at The Clockworks in April.

Lee’s research covered clocks, pocket watches and wristwatches, and looked at type and numerals used on the dials, identifying various themes and typographic pitfalls that appeared to be specific to wristwatches.

His research included interviews with brands and independent watchmakers about their typographical decisions, the typefaces they use and the importance of type design to their brand.

His talk focused on the typography of contemporary wristwatches that had revived distinct vintage or antiquarian styles.

Highlights included the use of system (or default) fonts by high end watch manufacturers, the technical limits of pad printing, the benefits and traps of modern processes involved in dial design (such as the digital workspace) and inconsistent choices made by watch brands when reviving older designs. Examples of recent wristwatches from Longines, Nomos and Stowa were used to illustrate these themes.

As a codicil, Lee discussed recent advances in dial printing, such as the use of physical vapour deposition on the zirconium ceramic dials of the Charles Frodsham Double Impulse Chronometer, suggesting that this technology might be taken up by other watch manufacturers, necessitating an increased focus on typographical principles and design choices.

Follow The AHS on Instagram: @thestoryoftime

Lee Yuen-Rapati: @onehourwatch

Mat Craddock: @the_watchnerd

Mr Satori fuses quartz

This post was written by Tabea Rude, Vienna Museum

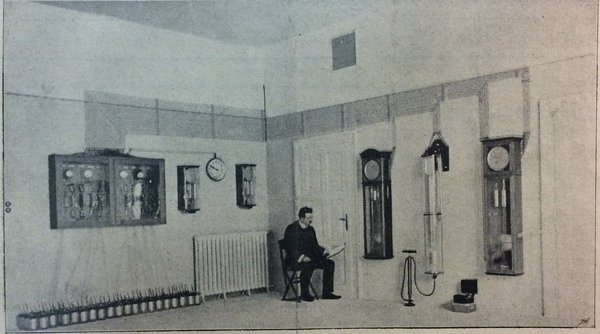

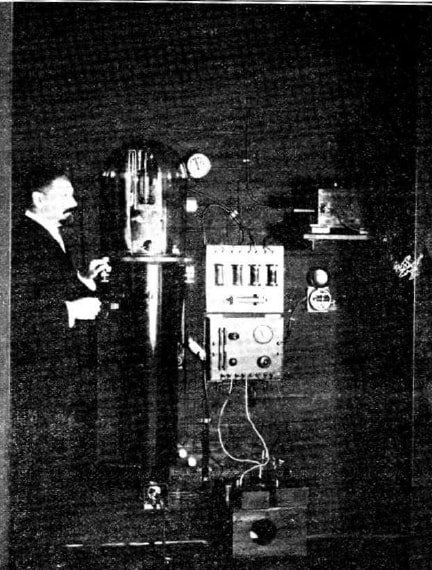

Around one hundred years ago, on May 15th 1918, the newly founded, not yet opened Vienna clock museum receives a generous present: a clock movement fitted with a fused Quartz pendulum rod.

It is installed in a most prominent position: right next to the entrance, in a case with a fully glazed front. Visible to every passer-by, it draws attention to the narrow house with its hidden treasures in the heart of Vienna.

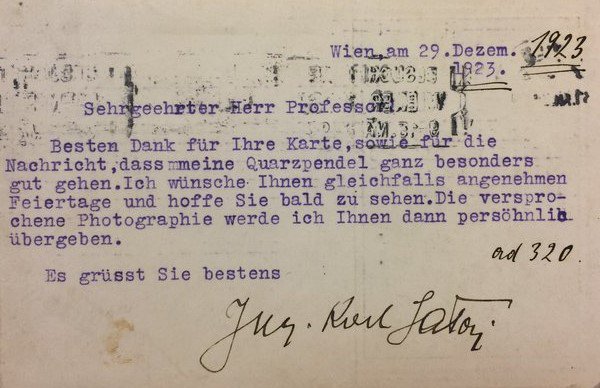

This donation was the beginning of a long lasting correspondence between the clock museum’s director Rudolf Kaftan and the engineer, donor and inventor Karl Satori.

Originally from Hungary, Karl Satori is first mentioned in the proceedings of the international electrical society (Internationale Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft) in Vienna aged 24, explaining Lorentz electron theory.

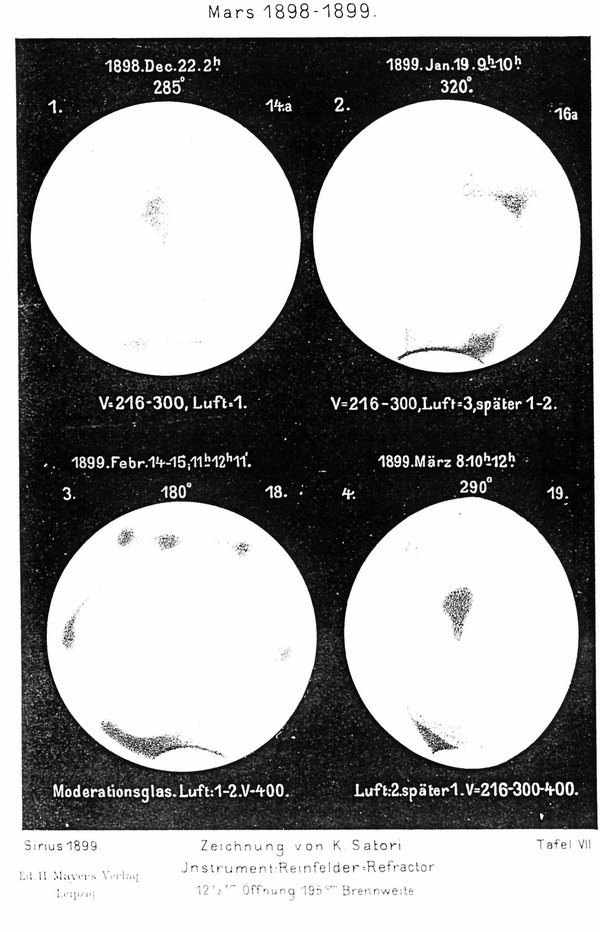

In the following years he delves into astronomical observation and planetary documentation and builds up professional relationships in the astronomy scene.

Soon he joins the international astronomical society and files his first patent in 1903: an electrical rewind system for clocks.

His professional career blossoms, allowing him to invest in his own private observatory in Vienna.

Around the same time, he is also given the opportunity by the Vienna electricity works to build up his own laboratory and to equip the Viennese Urania observatory with an electric time system which synchronized all public clocks in Vienna. This supplies the time signal as so called ‘Urania-Zeit’ to all telephone owners.

Besides his involvement in astronomy and several other clock related patents, he was also very keen in exploring pendulum materials and different methods of air pressure and temperature compensation.

Recognizing the unfortunate jumps steel pendulum rods experience during temperature changes and their reaction to magnetic fields, he experiments with fusing quartz into seconds pendulum rods. In 1912 he files his patent of the quartz pendulum.

One year later he opens his own precision workshop for mechanics and clock making. Satori expands, fuses quartz, files patents and ensures that the Vienna clock museum is placed to show the most cutting edge Viennese horological technology of its time.

Redisplaying the York automaton clock

This post was written by Daniela Corda

Over summer 2018, Matthew Read, Director, Bowes Centre, and I were commissioned to condition survey, part disassemble, pack for transportation, and reassemble an eighteenth-century automaton clock on behalf of York Museums Trust.

Originally assembled during the 1780s, this highly ornate clock was most likely designed for the export market and – although unsigned – has long been attributed to the London inventor James Cox (c.1723-1800).

The compilation of written and photographic condition surveying helped update museum records, inform current and future care, and outline operation options.

In its new permanent location in the Burton Gallery at York, the clock is on open display for the first time. Preventive measures were taken during reassembly such as the insertion of Melinex® film behind the case frets to restrict dust entering the case.

Under normal operation, the clock performs a 360-degree audio-visual show that includes rotating glass rods simulating waterfalls; automata pastoral scenes; spinning stars; jewelled contra-rotating flowers, and dancing cast-figures. In addition, the clock plays a sequence of seven melodies on a nest of eleven bells, striking the quarters too.

A detailed treatment report from York Castle Museum, dated 1982, indicates the clock has undergone many repairs, alterations and layers of reinterpretation, including the replacement of a pipe organ with a nineteenth-century Swiss musical box mechanism.

In its present state the clock has six main functions:

- Clock mechanism indicating hours, minutes, seconds, 1/5th seconds, date and age of the moon

- Quarter striking

- Hour striking

- Automaton musical train

- Automaton drive mechanism

- Swiss musical box

The majority of these dynamic elements are able to function, thanks to major renovation upon the object’s acquisition in 1974. So, although the clock can run, the overriding question is: should the clock run?

As the single dynamic historic object on show at the Gallery, running the clock adds tangible and intangible value for visitors, but comes at the cost of further cumulative damage. The present arrangement is to run the clock’s main movement, authorising the ticking sound, the hour and the quarter striking, but only to operate the automata elements at scheduled times.

Digitisation methods are being considered to build into wider conservation plans. Following prior research into microcontroller electronics, this object can benefit from implementing digital strategies such as recording audio aspects, reversibly relieving the mechanical movement from operation, and therefore wear, without experiential losses.

This ostensibly straightforward project highlighted inevitable emotional, mechanical, philosophical and conservation collections care questions. The clock can be seen at York Art Gallery with automaton demonstrations on Wednesdays and Saturdays, 14.00.

And now for something different

This post was written by David Read

In the world of watch collectors there are many who dislike finding that a pocket watch case has been engraved with the owner’s name, or to record it being given as a present. My feelings are different. An engraving not only provides a date which can be useful information, but can also point to an interesting history.

Late one evening in November 2000, I was watching a BBC documentary about the Yukon Gold Rush when the name Skookum jumped out at me.

In turn, I jumped out my chair because some years earlier at a NAWCC meeting in Florida, I had acquired a 14 karat gold E.Howard & Co. pocket watch retailed by Joslin & Park of Denver Colorado.

E. Howard & Co. made some of the finest watches in America so it interested me, as did the inner back which was not the same colour of gold as the rest of the case. And engraved on it were the words, 'A relic of Skookum Gulch March 22nd 1897'. It was certainly something different.

When the Yukon documentary finished, some quick research on the Internet led me to an email address for the Yukon Prospectors Association and before going to bed I sent questions with attached images.

In due course I received a reply from a member, himself a prospector who had searched for gold and experienced the thrill of finding it.

The following summarizes what he wrote:

'Gold was first discovered at Skookum Gulch by Joseph Goldsmith and his partner on 22nd March 1897, the date engraved on your watch. Arriving in the Klondike area too late to stake a claim on one of the major creeks, he prospected the feeders and found rich gold in this one. Goldsmith staked the first claim and named the stream. He, or perhaps his partner, used some of the gold to have a replacement inner cover made for the watch. The gold will be from the original panning and is significant in that it marks an historical event'.

Discovering a Japanese lantern clock

This post was written by Daniela Corda

As a Post Graduate Diploma student of the Conservation of Clocks program at West Dean College, one of my recent projects has been to restore safe working order to a Japanese lantern clock belonging to the Russell-Cotes Museum, Bournemouth.

Museum records classified the clock as Chinese, however, after conducting initial research, it became clear that the object conformed to many stylistic features of lantern clocks from the early-mid period of Japanese clock making.

Some of these features are indicative of the temporal time system employed in Japan during the country’s Edo period of isolation (1603-1868). It was not until 1873, during the Meiji Reform, that mean-time and the European calendar were adopted.

- Two-winged bell nut

- Deep bell

- Verge and foliot escapement

- Rotating 'warikoma' dial

- Latched case

- Posted iron frame and iron mobiles

The Japanese temporal system divides the day into 12 hours, rather than 24, and six of these 'hours' are proportional to daylight and six to darkness. Hence, the adjustable numerals are designed to accommodate variable time intervals within the relative lengths of day and night by season.

The numeral characters are engraved with the traditional 9-4/9-4 numbering, using the zodiacal names of the hours, which count down in reverse order.

During the process of recording and documenting, a conservation approach was employed focusing on stabilising the clock in its current condition. Treatment included fabricating missing parts and the mechanical removal of corrosion with a custom made mother-of-pearl scraping tool, a material that retains its shape but is softer than the substrate, so becomes sacrificial, reducing the risk of damaging the ironwork.

During Japan’s isolation, the temporal time system suited the predominantly agricultural society; concurrent competition in Europe for the longitude prize was not of their concern. Therefore, it is important to refrain from imposing western motives, descending from a precision-driven approach to clock making, onto an object that has come from a very different context.

Considerations for future work include analysis of the brass alloys and the coating used on the ironwork, as well as investigating the lacquer present on the calendar wheel (pictured above) aiming to provide a more detailed narrative of the social and craft context surrounding the clock. Due to its age a stable environment and restricted running hours will be imposed on the clock to mitigate further losses.

The popularity of horological tattoos

This post was written by Anna-Rose Kirk

Clocks and watches are the most tattooed image at the moment according to Vice magazine, and tattoo artists are sick of tattooing them.

'Clocks. Clocks, pocket watches and more clocks . Mostly on guys in their mid 20s. There must be hundreds, at the very least, being done in the UK every week. Lots of tattooists have stopped putting them in their portfolios because they’re so fed up with them' (Craig Hicks).

Time symbols have always been popular in art as reminders of the passing of life and the inevitability of death.

Hour glass tattoos have been a simple depiction of this for many years, and there has been a long tradition of symbolism within prison tattoos depicting clock and watches with no hands. However, the more recent need to capture time has sparked a trend of more complicated depictions and designs within larger tattoos often surrounded by banners, flowers, and owls.

Speaking to those that have the clock or watch tattoos, it is apparent that the most common reason was the idea of symbolising a date and time, a child’s birth for example, and was a way of avoiding text and numbers which have become a common tattoo choice.

Others wanted them as reminders that time is precious and had them tattooed in prominent places as a constant reminder to live their lives meaningfully.

One person I spoke to simply had a deep appreciation for horology and the way that watches worked after coming across them in his job in a jeweller’s and from his friends in the industry. Because of this, the time on the watch does not have a significant meaning, but it was important to him that the detail and the way it looked was right.

Celebrities and easy access to images and discussions play a part in tattoo trends but simply more people are getting tattooed meaning particular images seem to get used more often.

I wanted to get to the bottom of whether clocks and watches were seen as something mysterious with no concept of the inside workings, however, although a lot of the general public, especially the younger generation, does not understand the exact mechanics of a pocket watch, they have a tangible feel which in contrast to today’s sleek, minimal, computerised technology can feel a lot more real. They feel as if the have a history and a story; linked to memories tradition and ritual.

I wonder if a rise in nostalgia and a romanticism for craftsmanship and the handmade has brought about the rise of this style being used in tattooing and movements like Steam Punk.

It is perhaps a fight against excessive consumption of the 21st century and the dehumanisation of manufacturing and the idea that traditional skills may be lost. It seems to be that horology is being worn as a symbol of authenticity and a preservation of history in a vain attempt to show that this generation care.

The compound pendulum in a precision timekeeper?!

This post was written by Tabea Rude

Popular and well known examples of compound pendulums in horology are found in French novelty clocks. They can be camouflaged as an innocent sailor, as in the mantel clock on display at the Royal Observatory Greenwich...

...but mostly compound pendulums are regarded as a nightmare when it comes to precision.

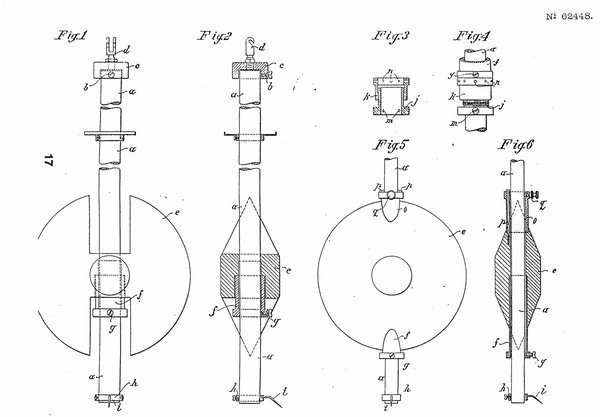

This was not always the case, as I found out in the conservation and research into an electromechanical double pendulum clock, patented by M. Pierre Sellier in 1909.

Sellier’s patent clock (on display at The Clockworks) uses a compound pendulum to provide the drive to the hands, while a ‘free’ pendulum controls the electro-magnetic impulsing of the compound pendulum, by making and breaking the drive circuit.

Sellier’s invention was, like most other compound pendulums, lacking in precision, but in the early 20th century he was not alone in using a compound pendulum in the quest for precision time keeping.

In other horological circles, consideration was given to the compound pendulum as a potentially useful component.

While in 1909 the Deutsche Uhrmacherzeitung described the compound pendulum as a ‘rape of the pendulum principle’, a major article by Prof. Dr. Ing. H. Bock in 1929 in the same magazine reported on a compound pendulum as a precision break-through.

After criticising the suspension spring type used in Shortt’s free pendulum for its variable elasticity modulus, Bock introduced Dr. Max Schuler’s idea of exchanging Shortt’s free pendulum for a compound pendulum resting on a knife edge.

He claimed that Schuler would soon be able to measure all the anomalies in the Earth’s rotation and outperform the Shortt clock with ‘German toughness’.

The Schuler clock has ended up at the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum at Furtwangen, and no doubt we will hear more about in due course!

AHS Wristwatch Group

This post was written by Laura Turner and Rebecca Struthers

The Antiquarian Horological Society is pleased to announce the formation of a new specialist group focusing on the emergence and development of the wristwatch.

There has been an increased interest in vintage and antique wristwatches in recent years, but a perceived lack of corresponding published scholarly research. The Wristwatch group plans to promote and encourage the study of the history and development of wristwatches, through meetings, education and publications, including articles in the Journal or technical papers for Group members.

Members of the Wristwatch Group will have regular meetings, in the form of lectures, short talks, bring and discuss sessions, and visits to exhibitions, private collections and centres for the practice and study of watchmaking both in the UK and abroad.

The Group will bring together enthusiasts keen to learn more about the origins, makers, techniques, family and corporate histories and indeed any of the material and cultural aspects associated with wristwatches.

All are welcome, whether new to the subject or recognized authorities.

The group will be chaired by Rebecca Struthers, watchmaker and doctoral researcher of antiquarian horology at Birmingham City University, along with Laura Turner (secretary), one of the curators of the Horological Collection at the British Museum, supported by Mat Craddock, and Tracey Llewellyn, editor-in-chief of specialist wristwatch publication Revolution magazine.

Announcements of forthcoming Group meetings (and subsequent meeting reports) will be included in Antiquarian Horology, and will be listed at www.ahsoc.org and via our subscription mailing list.

Membership of the Group is open to any member of The Antiquarian Horological Society.

To join the Wristwatch Group, or to find out more, please email wwg@ahsoc.org.

Fine timing

This post was written by Paul Buck

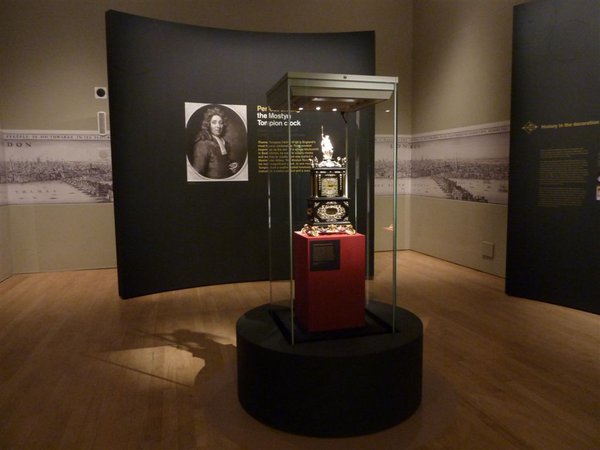

A new exhibition has opened in Room 3 at the British Museum displaying the year going table clock by Thomas Tompion. This magnificent clock celebrates the coronation of William III and Mary II in 1689, and was kept in the royal bedchamber. It was made by a talented and industrious man who was in the right place at the right time.

Tompion’s modest beginnings as the son of a Bedfordshire blacksmith are recorded, but after that nothing is known of his whereabouts until he appears in London at the age of 32.

Wherever he had come from, he was extremely well trained in the making of clocks and watches.

London 350 years ago was the ideal place for Tompion’s genius to shine. In the previous century, religious persecution in the Netherlands and France had led to an exodus of Protestants, including many goldsmiths, silversmiths, engravers and watchmakers who established their trades in London.

Despite the Great Fire and the plague that preceded it, 1670s Restoration London was prosperous, with a plentiful supply of wealthy clients to support the burgeoning clock and watch trade. The new accuracy in clocks resulting from the application of the pendulum in 1657 followed by the balance spring in watches in 1675 was of great interest.

When William died the clock passed to Henry Sydney, Earl of Romney, Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Groom of the Stole. On his death in 1704, it passed to the Earl of Leicester and then to Lord Mostyn and remained in that family until 1982.

It is now known as ‘the Mostyn Tompion’ after its former owners.

The clock continues to keep good time, and is notably ‘year-going’ – it runs for over a year on a single wind. It also strikes the hours, an annual total of 56,940 blows on the bell.

This free exhibition is timed to coincide with the 300th anniversary of Tompion’s death in November 1713 and runs until 2nd February 2014.