The AHS Blog

Plastics in horology- AHS funded PCIP course

This post was written by Tabea Rude

In order to gain a wider understanding of the conservation of plastics, its history and its newest applications, the AHS recently paid for me to attend the Conservation of Plastics short course taught by Yvonne Shashoua at West Dean College.

This course proved to be advantageous for an investigation of the degradation of insulation materials in Post Office Type 36 time transmitters as part of the MA Conservation Studies programme at West Dean College.

During the course it became evident how interlinked plastics are with our life.

Starting off as a random material with varying compositions, cooked up in private households it developed to a diverse material invading every corner of our universe.

As a material between waste and high precision engineering, plastics are subject to multiple dilemmas, one of them being its conservation for future generations.

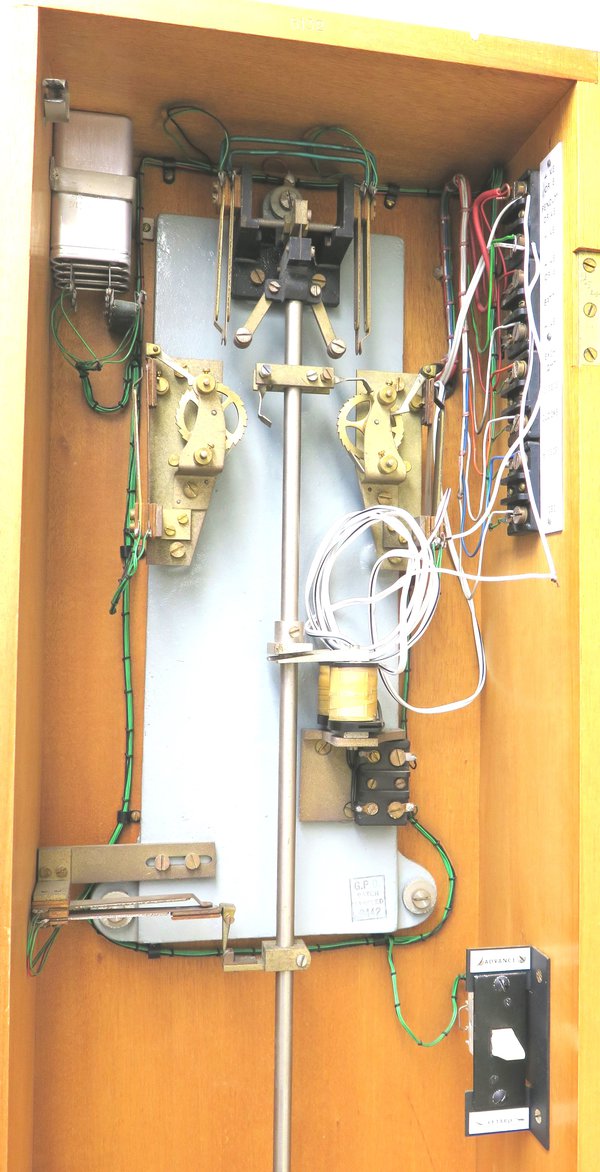

As part of the course, identification techniques were discussed and carried out. By exploring the properties of different plastic families, it became clear that a mixed media object such as the Post Office Type 36 time transmitter, containing at least five different types of plastics, metals and wood, would challenge preventive conservation techniques.

Some plastics such as PVC, often used for wiring in the PO Type 36, should be kept enclosed to avoid the loss of plasticiser. However, other plastics, that tend to off-gas, should be subject to an absorbent such as Zeolite, Silica gel or activated carbon.

On that account preventive conservation of mixed media objects such as the PO Type 36 is at best a compromise.

As a result, this course was an eye-opener to a material we take for granted today. Experiments conducted within the framework of the PO Type 36 study were significantly influenced and informed by the course and discussions had with conservators working in the field of plastics.

A 68 minute weight – with verisimilitude!

This post was written by Jon Colombo

At West Dean College, first year clock students make a hoop and spur wall clock from scratch. As far as practicable we use techniques available to an eighteenth-century clockmaker. This gives the deepest understanding of the mechanics, aesthetics and the way historic clocks are put together. Verisimilitude is important, but not critical. When making driving weights, students usually use brass tube, topped, tailed and filled with lead. As a former archaeologist, I wanted more authenticity.

Examining a selection of old weights showed:

- The joints do not seem to be soldered. Under a microscope, often the seam is marked by a thin copper-coloured line, likely to be loss of zinc from the brass.

- The joints are not brazed. It is common for the skin to split along the joint. Were they brazed, failure here would be very rare.

- Often the lead has shrunk away from both sides and hanger, leaving a hollow tube running down into the weight.

- The bottoms are almost always domed.

The first two suggest a butt joint. The third that the lead is stuck to the skin. It could be just the filling holding the whole thing together. Cooling shrinkage cooling would pull the skin into compression, and explain the need for domed base. The logic was convincing; time to try it.

I cut a skin and domed base of thin brass sheet, tinned and wired them tightly together. I then embedded the shell in sand and poured in lead.

Manufacture is simple, quick, economic – sheet formed on bar, butt joint filed, wired up and ready to go; hanger made from old wood screw.

The results were pleasingly close to the originals. The lead bonds firmly to the walls, heating them enough for the outside to take on a copper colour. In cooling the lead pulls the joint tight and forms the right shrinkage patterns. When I cleaned the weight, the copper colour was often left in the now very tight butt joint.

If you fancy giving it a go, or are simply curious, http://westdeanconservation.com/2014/06/05/a-68-minute-weight-with-verisimilitude/ gives a bit more detail.

Conservation and repair of a mystery clock

This post was written by Kenneth Cobb

A disassembled glass and ormolu mystery clock was sent to West Dean College from overseas to be reassembled. A simple enough request, however the 1850’s mechanical mystique of smooth running remained a challenge throughout the three month process.

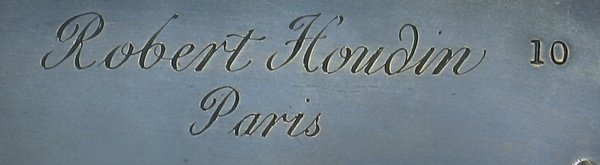

The clock was made by Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. Born into a family of watchmakers in Blois, France, he was primarily a conjurer and practical joker and this clock is no exception as it is Robert-Houdin’s ‘Fourth Series’ of Mystery Clocks. Onlookers would have wondered at the science of telling the time without the hands being attached to conventional clockwork.

One of West Dean’s key strengths is that conservation departments work together, thus the glass was cleaned by students in the Ceramics Department and advice on cleaning the ormolu was supplied by the Metals Department. Typical of the West Dean conservation approach is Robert Houdin’s signature in copper plate writing on a plate, which was left with the patina as received since it is stable.

The movement itself was a challenge as previous repairs had probably exacerbated its primary weaknesses: the plates are long with a minimum number of pillars to support the tensions of twin sprung barrels thereby making the movement unstable. The lead-off work was hidden within the body of the object. There were so many interconnected links that it was not clear which connection or link was at fault: a question that took weeks to resolve.

Finally, the clock ran reliably and sadly had to be returned as it was a considerable source of interest. As a student, the clock was been a privilege to work on having been a great source of learning and patience, and under the tutorship of Matthew Read and Malcolm Archer I have gained a lot more understanding and confidence in this field.

A telescope by Henry Hindley

This post was written by Tim Hughes

The work of Henry Hindley of York was researched by Rodney Law and published in Antiquarian Horology (1971/2). The article describes two equatorially mounted telescopes signed Hindley.

The first of the two telescopes forms part of the collection of the Burton Constable Foundation, East Yorkshire, and the later instrument is now in the collection of the Science Museum London.

In recent months, the earlier instrument (circa 1740) has been through a process of conservation cleaning and close study by Tim Hughes of West Dean College.

The instrument is regarded as of significance and is known to have been purchased by William Constable for use in the eighteenth century observations of the Transit of Venus. The telescope mount bears much resemblance to that by James Short published in Philosophical Transactions in 1760, having meridional, equatorial and declination circles over a primary setting circle.

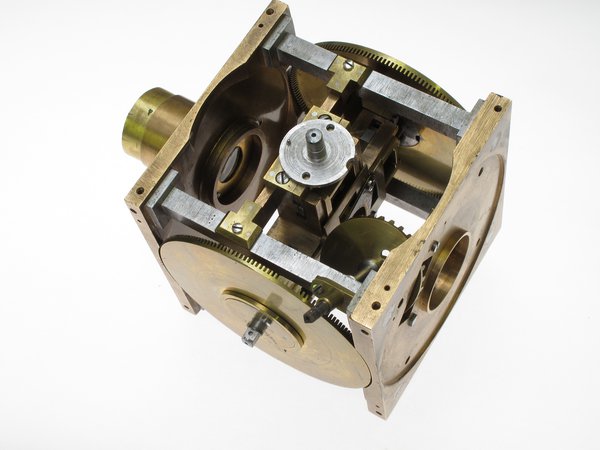

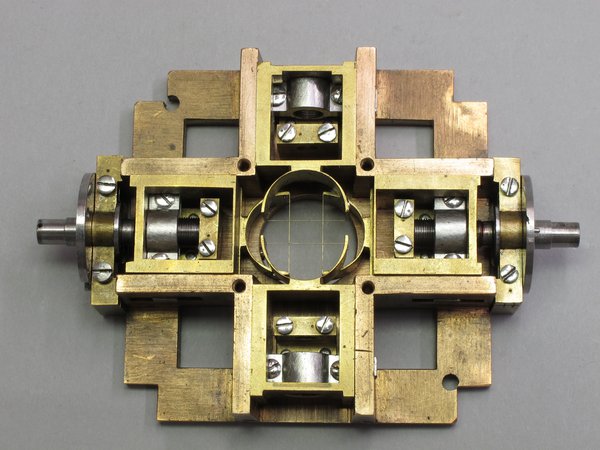

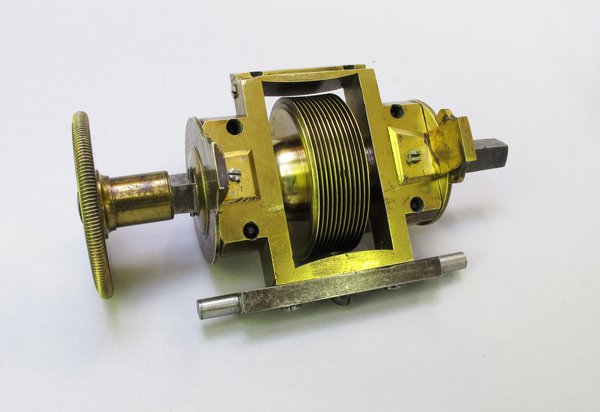

Interestingly, Hindley’s telescope mount is a combination of sound mechanical clockmaking practice – including the very precise and beautifully made worm gearing – and surprisingly unstable telescope mount which raises questions about the development process and Hindley’s involvement with the various stages of manufacture.

The instrument is signed on the micrometer box only, which is in itself a piece of clockmaking genius. Within the box are fitted four reticule frames, connected by intermeshing contrate wheels operated by a setting knob. The reticules form an adjustable square frame within the field of vision allowing angular measurement of the size or distance between objects.

Work on cleaning and recording the instrument is almost completed and has been assisted by Charles Frodsham and Company Limited who have kindly carried out measurement of the gearing of the equatorial circle and its driving worm.

Once re-assembled, we intend to carry out field tests with the help of a professional surveyor in order to better understand the calibration and range of the instrument which may further inform its purpose and limitations. A paper giving a technical description of the construction of the instrument to appear in AH in due course!

Job done!

This post was written by Matthew Read

Public clocks that don’t work; there are thousands of them. An irritation, sign of the neglectful and difficult times or simply a reflection of the lack of need for the dissemination of time in that format? Big questions but in this case a relatively simple solution with interesting conservation issues thrown in.

The plan to reinstate the long-dilapidated village hall clock with a modern equivalent. Easy reliable low maintenance solution? But what actually happened to the earlier clock? Did it still exist? Could it be reinstated? Questions sometimes make things more complicated but in this instance, the result was felt to justify the extra energy.

The re-discovered clock was probably originally installed in the 1930’s; Smith mains synchronous movement with hand setting by leaning out of the window to reach the adjusting knob. Although potentially perfectly serviceable, due to the mains voltage and window leaning out of combination , it was decided to replace the movement with a low-voltage slave, controlled from inside the building (the original movement packaged within the clock case.

The painted aluminium dial had discoloured with parked hands and some corrosion. Repainting the dial would have obliterated the original/existing surface so a decision made to copy the dial on the reverse, thus preserving what existed and the dial was turned inside-out.

Happy villagers, public time restored, happy conservation compromise, job done.

The Empire Hall was built in 1907 for the village by James Buchanan (later Lord Woolavington) of Lavington Park.

As one journey ends another begins

This post was written by Matthew Read

It was with some sadness (weep!) that postgraduate and MA students Francoise Collanges and Brittany Cox recently fled, or rather graduated from the West Dean nest. Over the summer period they completed their practical MA projects and accompanying 12,000 word theses.

Both Francoise's work in the study of early electro-magnetic clocks and Brittany’s in the materials used inside automata that smoke (!) will undoubtedly add value to the body of knowledge in these specialist fields. During the process, a lot of fun, blood sweat and tears ensued. Result! We wish them both well.

Early October saw the intake of new students and the welcome back of those returning. All students new to the clocks programme at West Dean begin their long journey through horological bench craft skill by designing and making their very own clock.

As a beginning, clockmaking embraces so many of the materials, tools, techniques required for later life as conservator restorers. The world of turning, soldering, filing and scraping, geometry, mechanics and a little mathematics thrown in is a demanding one, and interestingly, the outcomes from what is outwardly a uniform process, are as diverse as the students themselves. Christmas should see trains and frames completed, entire clocks by awards day 2013.

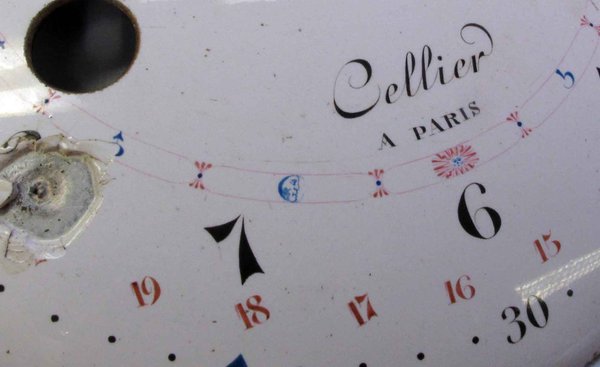

Returning students on Diploma and Postgraduate programmes are working on historic clock projects. These span sensitive cleaning and conservation of a mystery clock by Houdin, through the repair of an imposing ormolu mounted mantel clock signed Cellier, to the reinstatement of verge and crownwheel escapement to an early eighteenth century spring clock.

Many of the projects are multi-media and therefore require interdepartmental liaison in the conservation and repair processes. Never a dull day in clockmaking.

As always, lots to do, lots to see.

West Dean holds its Open Day on Saturday 10th November 2012. All welcome. See www.westdean.org.uk

Friends reunited?

This post was written by Matthew Read

Revisiting the Bowes Swan this week – the first time since it was completely disassembled in 2008 – was a personal and surprisingly profound experience.

There is a blogged account of the 2008 conservation project on the web site of the Bowes Museum. That project was at least from my perspective, a commercial professional endeavour, and very hard work!

As the intervening years have passed, some of that professional objectivity has slipped and allowed the Swan and the wonderful Bowes museum to become part of me. Yes, and of course, one can dine out on a project like that for a very long time indeed.

However, snapping back to hard reality, the swan is a bunch of clockwork, levers, cams and ingenuity, and the purpose of this recent visit was to see how everything has stood up to nearly four years of use.

The automaton being played once a day every day the museum is open to the public. Well, of course, as would be expected, it’s a mixed bag. Heavily loaded bearings and working surfaces take the brunt, some mid-twentieth century restorations do not fit quite so comfortably with the eighteenth century, yet overall, the policy of maintenance, observation and importantly, engagement by staff at the museum, seems to be striking that very fine balance between cost (in the widest sense)and benefit.

So the show goes on, the public watch, children stare, almost everyone films and photographs, and often the daily performance receives a round of applause. If you haven’t already, you really should see the sensual and magical swan in action. The Swan is operated daily at 2.00 pm.

Making a 19th century battery

This article was written by Francoise Collanges

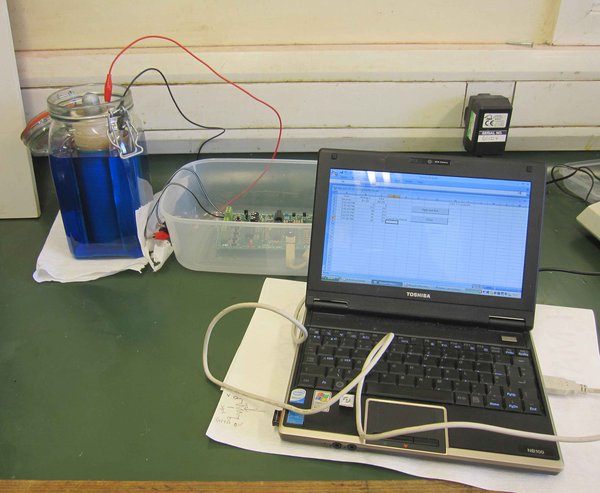

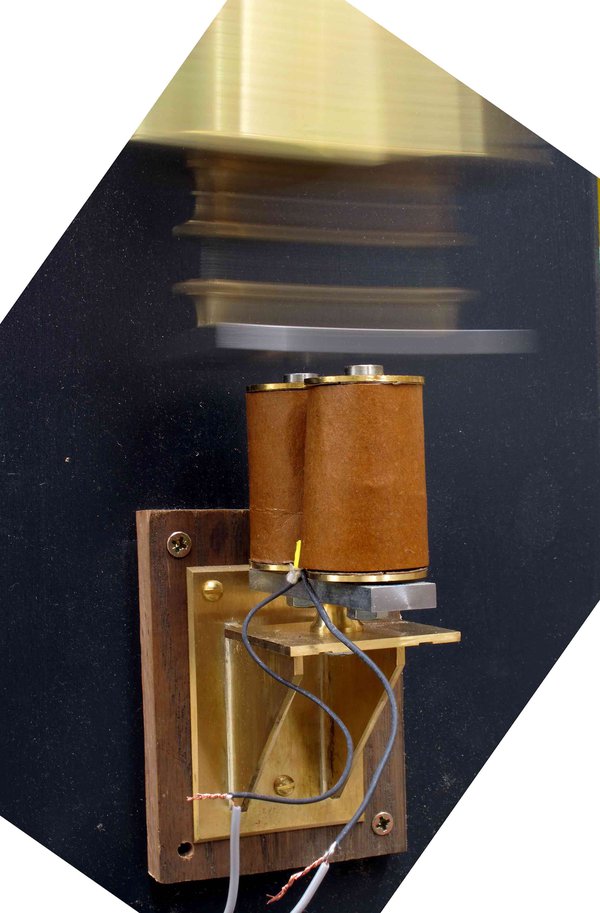

My MA project involves making a copy of elements of a mid-19th century electro-mechanical clock in order to see what the process could bring to conservation as a research tool.

One question was how the clock was originally powered and would it be possible to reproduce this today? Research revealed that power was supplied from a type of cell invented in 1836 by John Frederick Daniell, who gave it itsname.

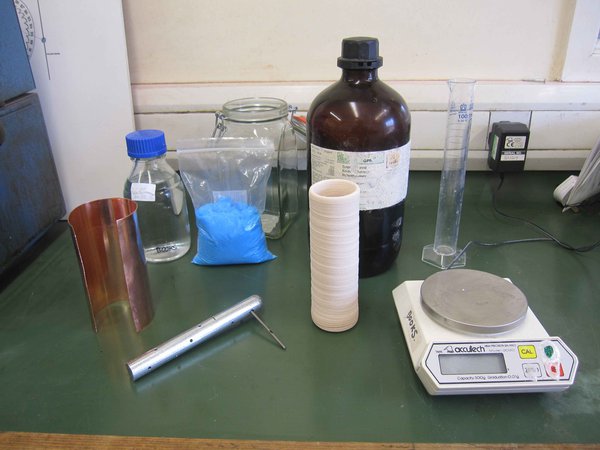

The next questions were: how was the Daniell cell constructed, would it produce a constant enough current for reliable operation of the clock and would the voltage be similar to a contemporary cell? With the support and collaboration of two other West Dean Clocks Programme students, Jonathan Butt and Kenneth Cobb, materials were gathered.

In order to re-create a Daniell cell, the following was needed:

- A porous vase (kindly provided by Alison Sandeman, West Dean pottery tutor).

- A zinc anode (as typically still used for boat protection).

- A copper pipe.

- Sulphuric acid solution.

- Copper sulphate.

- A glass Kilner jar.

As soon as the sulphuric acid was added, the reaction started – the solution inside the vase started to fume and bubble and the cell produced current at its maximum voltage of about one volt. The cell worked constantly for five days (before the porous vase collapsed), with only minor intermittent drops in output (0.2 volts). During this time, the solution level within the vase dropped to almost half, copper crystals formed on the surface and thick crystals were visible at the bottom of the glass jar.

So we successfully made and tested a cell as it may have been made in 1836. Even with testing and research far from finished, it can already be said that:

- this clock was powered with a voltage even less than a modern 1.5 volt battery.

- it did not draw a huge amount of current from the cell, so the life length of the cell should have been of several days at least.

Furthermore, these results suggest that early electric clock systems were used in a different way from how we generally perceive them today.

Meet Radcliffe

This article was written by Brittany Cox

Meet Radcliffe: he has real feet, wings, beak, body – the makings of a living bird, but without the squishy inner bits. They were traded over a hundred years ago for clockwork.

The scarlet tanager is an American songbird, which belongs to the cardinal family and is known for its red plumage and black tail and wings. Attempting to identify the old relative at my desk proved quite challenging.

Radcliffe, as I named him, was faded, dusty, and the light in his once bright eyes had dimmed with age. He no longer resembled his vibrant cousins. After sending the Audubon Society some images, I was thrilled to learn his true identity and imagined him singing in the lush canopies of South America.

What a strange thing, to outlive and out sing all others of his species, for as a mechanized bird he will go on singing for decades to come.

Repairing Radcliffe was no easy feat. Among the various faults in the mechanism, a section of the clockwork for commencing and ceasing the performance was missing and the bellows for voicing Radcliffe needed recovering. Zephyr, a fine parchment-like sheet of pressed goat intestine, was used to recover the bellows. The paper valves, allowing and restricting the internal air flow between the bellows chambers, were replaced with a brass and plasticine system, which I found to be the most fool-proof method.

After restoring the start/stop function to the mechanism, there was one other matter to sort out before Radcliffe was ready for his performance. He had lost his tail feathers over the years, so I made him a sort of toupée…

Using brass paper clips, I made a little ‘clip on’ tail that can be easily applied or removed without damaging his body.

There was a time when Radcliffe sang just for me; now he is singing for all of you.

West Dean do the Hipp-toggle

This post was written by Matthew Read

At West Dean College, once in a while we take the opportunity to pack away the historic clocks, let our hair down and have some good clean horological fun making new stuff. New making is very much part of our wider philosophy – learning through doing – and what informs and prepares students for the restoration element of our work.

Following a chance discovery of a copy of Practical Mechanics 1936, complete with blueprints and instructions of how to build a Hipp-toggle pendulum clock, we could not resist the challenge.

The hipp-toggle system is one of relative simplicity, or so we thought so attempted the project in a single day. Well, relative simplicity is a relative thing, yet at the end of a frenetic day we had our clock ticking – complete with hand-made electro-magnetic coils, rather splendid (we feel) shellac lacquered, knurled brass terminals, pendulum bob and the like. With a nod to modernity, the pendulum rod is of carbon fibre tube and the electrical circuit sports blue LEDs.

So not to take ourselves all too seriously, we dressed for the day in proper kit, took regular breaks for tea and mandatory pipe smoking and workshop discussion was of the latest technological advances of the time – 1936.

See the completed clock and find out more about how this project will help student bursary funds in a future post.

The work of Matthias Hipp features in the excellent ‘Time Machines’ temporary exhibition at the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.