The AHS Blog

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

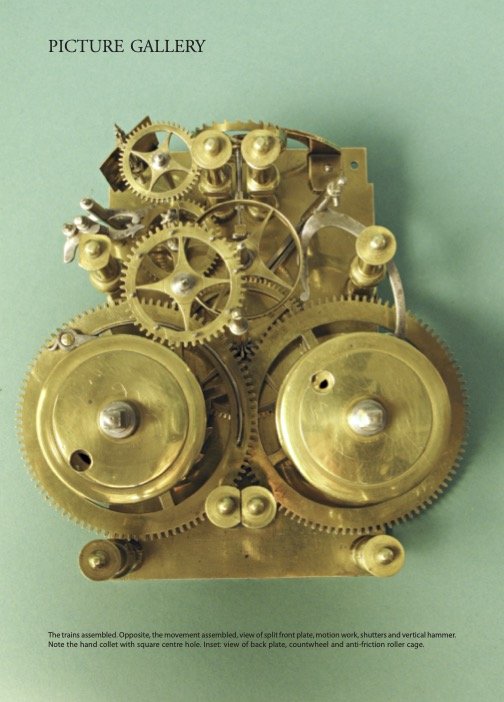

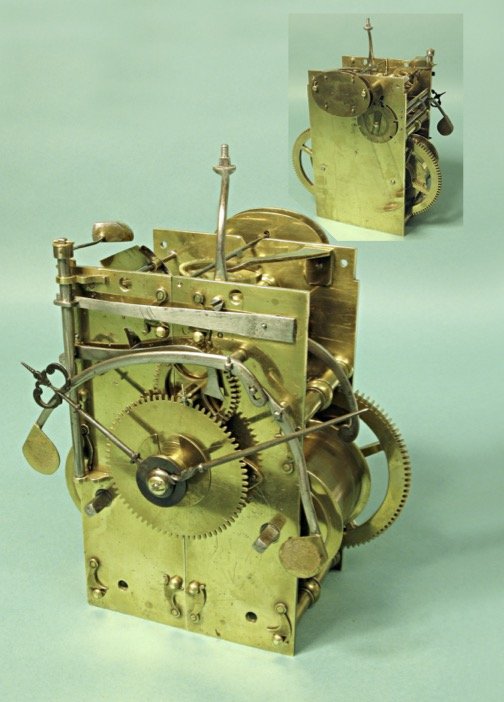

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Light among the lanterns

This post was written by James Nye

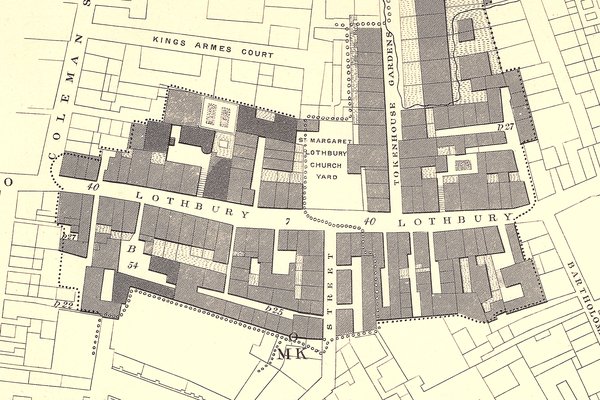

I used to walk regularly from Cannon Street tube station to the Clockmakers' Company office in Throgmorton Avenue, and on the way would walk down the west flank of the Bank of England, turn right and cross over to slip down Tokenhouse Yard. One day, passing St Margaret’s Lothbury, I stopped, and looked around. It struck me forcibly that Lothbury was really short, yet I knew that a fair number of lantern clocks were signed from addresses on the street. I was intrigued. Was this like restaurants crowding together and all benefiting from increased business?

This was back in 2018, and I conceived the idea of a deep dive into the street’s pre-Fire history. It was known for its founders, and for their ‘turning and scrating […] making a loathsome noise’. Was it such a bad place? Who else lived there, and what did they do? I recruited a research assistant, Caitlin Doherty, and together we planned trips to archives and libraries, following up hunches and leads developed together.

This all resulted in a lecture we jointly gave in November 2019, but I had to jettison more than half my material to squeeze it into a decent length. Then Covid struck and the larger work languished, until mid-2022 when I dusted it down and gave it a read. I was pleasantly reminded of much, but also conscious that a lot more could be done, so I strapped on the tanks and went overboard again.

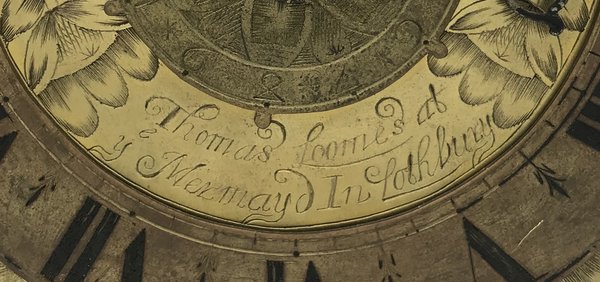

I was still frustrated that on the first attempt I had failed to pinpoint the location of the Mermaid, the best-known Lothbury address, home to Selwood, Loomes and others, and from which the first pendulum clocks were sold in London. A punch-the-air moment occurred earlier this year when I finally found archival documents that revealed its whereabouts.

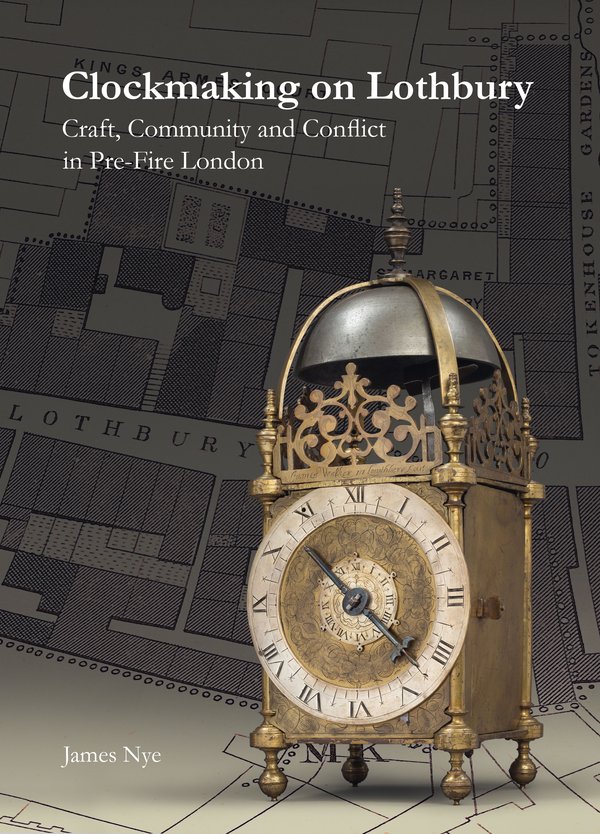

The project eventually grew to a book-length treatment and I am deeply grateful to the Society for backing its publication. It has recently been rolling through the presses. You can see pages being prepared for sewing here and the cover being embossed here.

Make no mistake, this is not a technical book about lantern clocks. But it is a forensic account of the small community in which one group of remarkable makers lived. It reveals who their neighbours were and the challenges they all faced, whether against the backdrop of the Civil Wars or the poisonous smoky atmosphere. It discusses the trades in which the merchants on the street were engaged, but reveals some of the poverty close at hand. I hope that in many ways it should throw some more light around the early life of many lantern clocks. And you can order it here!

Time's up!

This was post was written by Jonathan Betts

Have you ever had to endure a relentlessly boring after-dinner speech?

In these less-formal days there are fewer opportunities, but in the ‘good old days’ in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, when many of the elite of British society belonged to exclusive dining clubs, speeches could go on seemingly forever!

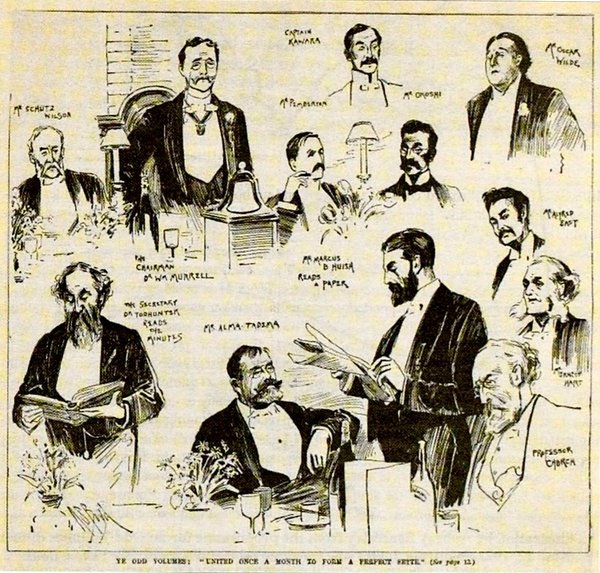

The Sette of Odd Volumes

The 'Sette of Odd Volumes', one of the more eccentric of such dining clubs, was founded in 1878 by the celebrated antiquarian bookseller, Bernard Quaritch (1819-1899). Over the following decades it was distinguished by having as members and guests many great achievers in the literary, scientific and academic worlds.

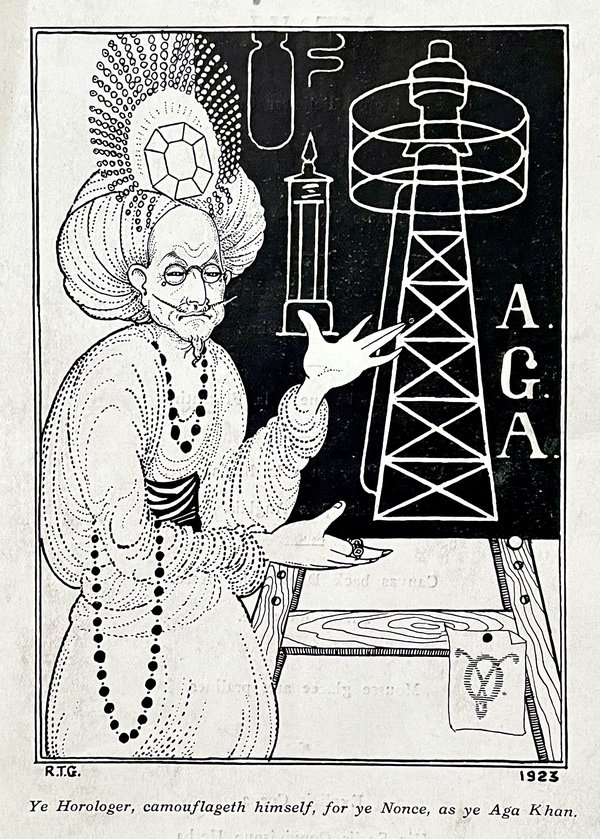

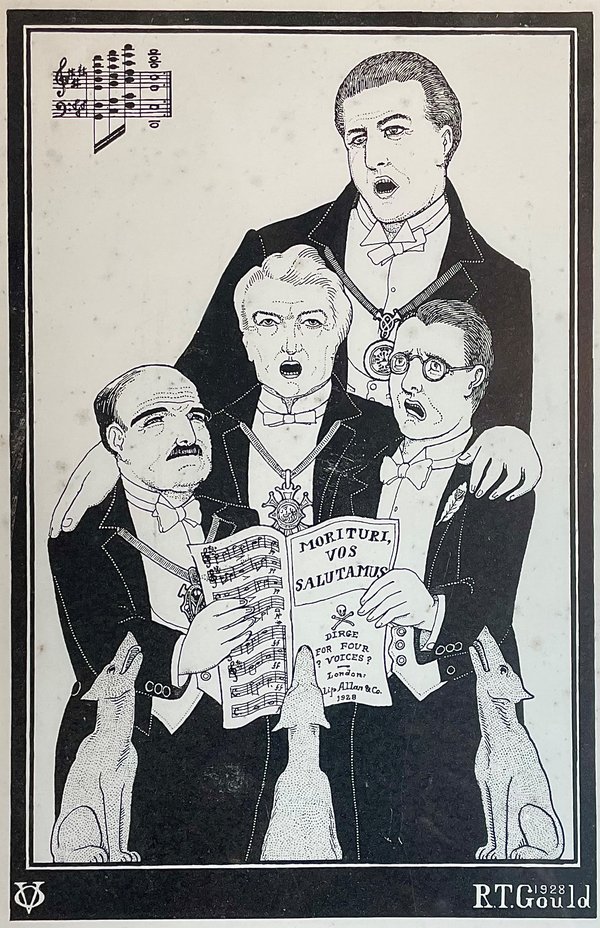

Horologically, our very own Rupert T. Gould (1890–1948) joined in 1920, and George C. Williamson (1858–1942), the antiquarian who published horology’s largest book, the catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan collection of watches, was also a member.

Members of the club were ‘brothers’ and adopted titles appropriate to their professions. Gould was ‘Hydrographer’ and Williamson was ‘Horologer’. The enforced, tongue-in-cheek jollity of the dinners required the exclusive use of their titles.

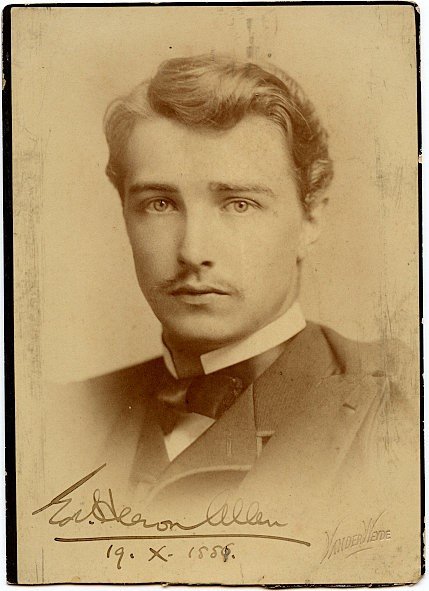

Oscar Wilde occasionally attended these Sette dinners as a guest. In later years, Wilde’s second son, Vyvyan Holland, was a Sette member, 'Idler', and was also a good friend of Gould's. Another great friend was the biologist and microscopist Edward Heron-Allen (1861–1943), ‘Necromancer’, who had joined the Sette back in 1883.

Each year, the Sette elected a new President, who sat in a grand throne-like chair when in office, and a Vice President, who would be President the following year. In 1891 Heron-Allen was about to be elected Vice President, and as a gift to the Sette (and as something of an aggrandisement to his new office!) he commissioned and presented a Vice President’s chair to accompany the President’s.

Those speeches

The Sette's activities were regulated according to a set of Rules, some of which were positively Pythonesque. For example, rule XVI was that 'There shall be no Rule XVI', and Rule XVIII insisted that 'No Odd Volume shall talk unasked on any subject he understands'.

One of the more sensible rules, however (No. XX), stated that 'No O.V.’s speech shall last longer than three minutes; if however, the inspired O.V. has any more to say, he may proceed until his voice is drowned in the general applause'.

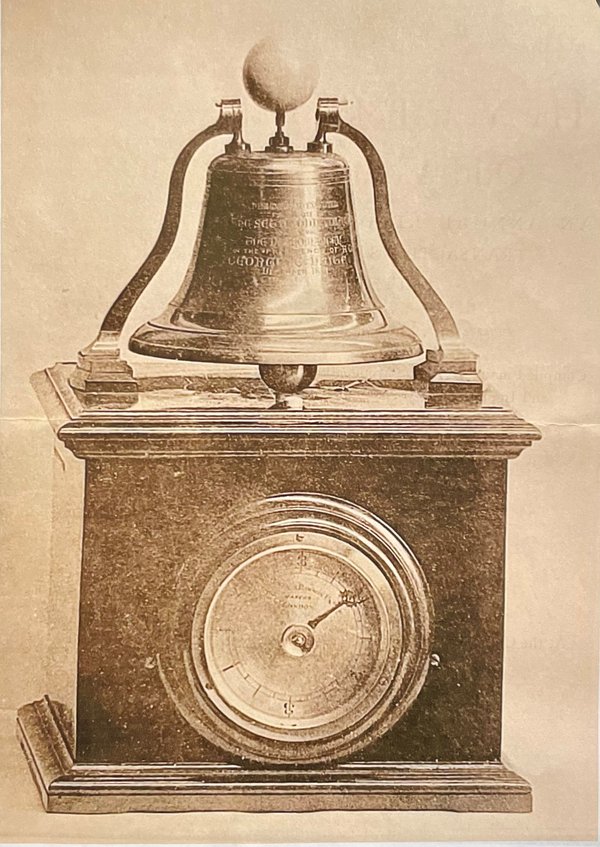

Finding that this rule was constantly being disobeyed, and that evidently the ‘general applause’ was insufficient, in December 1891 Heron-Allen also commissioned and presented to the Sette an elaborate speaker’s bell, to ensure they stuck to time.

The bell

Made by the well-known Victorian electrical engineers, Woodhouse & Rawson, the bell is of exquisite quality throughout. Constructed in a mahogany case containing the electro-mechanical timer, the large bell, mounted on the top, has a slender rod running vertically through it, which had (now missing) a ball on top.

In operation, reminiscent of the way a time ball runs, the timer is set going and the ball (which was probably an ivory billiard ball originally) is seen to slowly climb up from the bell. The ascent is controlled by a clockwork worm-and-fly governor, and at the point at which the three minutes has elapsed, the ball, now about 2.5 inches above the bell, suddenly drops back down to the bell, which then begins to ring very loudly, an electrical make-and-break hammer operating on the inside.

For the speaker, having a miniature time ball inexorably rising in front of him while he was talking must have been quite off-putting and, needless to say, the timing device was not popular. One can only imagine what Oscar Wilde would have thought (and said!) if the thing was set going as he began giving an after-dinner speech!

In fact, a certain flexibility was built into the controls of the bell, and the operator (presumably the Master of Ceremonies) was able to pause the clock, or even ring the bell in advance, if deemed necessary!

But its presence as a gift would soon be quietly but firmly removed anyway, and this fascinating and beautiful object, and the Vice President’s chair, were not seen again. This was owing to an incident which left Edward Heron-Allen unpopular among the elders of the Sette and which caused him to resign from the Sette a year or so later.

The incident, which is described in an excellent book by John Mahoney (The Richard Le Gallienne versus Edward Heron-Allen ‘Incident’ at The Sette of Odd Volumes, privately published, Tallahassee, 2023), concerned the proposal for membership of the Sette of the author and poet Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947).

Le Gallienne had had a brief affair with Oscar Wilde, and it seems that at the time he was being proposed for the Sette, Heron-Allen had made a remark in confidence at a private dinner party about Le Gallienne’s sexuality. Unfortunately, this remark was not treated in confidence, and Le Gallienne got to hear of it. This would, given the illegality of homosexuality at the time, be a very serious matter for him.

The scandal which ensued polarised views within the Sette, causing Le Gallienne’s election to be dropped temporarily and Heron-Allen to later resign. The chair and timer were thus quietly put away, though the chair does in fact remain in the Sette’s possession; the timer escaped at some stage and only resurfaced a few years ago.

For Heron-Allen the story ended happily, however. He would re-join the Sette thirty years later, and he enjoyed many a dinner with Gould, Holland and his other friends, no doubt having to put up with the long speeches after all.

A varied horological life

This post was written by Su Fulwood

'I have to ask you, is this your actual job?' This was put to me last week while I was winding one of the clocks in the collection at Goodwood House, the home of The Duke and Duchess of Richmond in West Sussex. Well, yes it is – one of them anyway, I do a few things.

I’m a freelance collections advisor, researcher and curator, so I work with all things from costume to archaeology, but more than half of my projects are horology related. Possibly this is because clocks, as something with a beating heart metaphorically, evoke memories and stories as well as encompassing art, science, technology and history, so as an example of material culture they are multifaceted and valued.

More than anything else, clocks are firmly connected to people, their knowledge and emotions. Working with them enables me to meet and work with excellent people, to travel, and it defines the places I visit.

I’ve recently returned from a job in York that enabled me to explore the coast from Staithes to Scarborough (I suspect turret clock specialists can relate to this).

This year began with a project working with the fabulous Cumbria Clock Company and their newer recruits. I can't express how privileged I feel to work with both experienced clockmakers and the next generation of horologists.

Back at Goodwood, I have an annual presence at The Festival of Speed and The Revival exposing me to all manner of wonderful cars, their clocks and watches.

My research on women working in horology with Geoff Allnutt also leads to fantastic places. The horology community is unlike any other and this introduction is also a thank you to all at the Antiquarian Horological Society who have supported me with my work. More to come!

An animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement

This post was written by Eliott Colinge

Visual representation has always been a core means to learn about horology and explore its principles.

The literature provides countless invaluable schematics about escapements, repeating mechanisms and patents of all sorts. Less can be said about video representations. If an image is worth 1000 words, what can be said about a video?

The recent popularisation of 3D animation in the film and gaming industry has gathered a wide community of brilliant individuals giving their improvements to the field at an increasing pace.

It is hardly possible to have a conversation about 3D animation without hearing the word 'Blender'. Being open source, the software has attracted students, researchers, professionals and amateurs around the world and is increasingly becoming a standard in the industry. Blender is such an incredible playground and I am always in admiration of what gets produced by the community.

As a trained conservator of horological artifacts, I founded the animation studio 'Vecthor' to provide complementary 'non-interventive' solutions to help education around collections.

Vecthor has made available a series of short animations of escapements based on drawings and a YouTube video about Pierre Leroy’s marine watch (available in English and French).

Here is an example through an animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement used in his marine chronometers during the 1770s. The impulse energy is stored in the coiled springs (constant-force) and transmitted to the balance during its oscillatory arc.

Other escapement animations can be found on Vecthor's instagram: @vecthor_animation

A sad commemoration

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A couple of weeks ago, I attended Bob Frishman's NAWCC conference on 'Great Horological Collectors' at the Horological Society of New York's home in New York City – a wonderfully successful and interesting event. By good fortune the date of the conference came just before a short holiday we had planned in New York, with passage home on the Queen Mary 2 – a delightful way to cross the pond.

When planning the trip I realised that, by a rather extraordinary coincidence, during the transatlantic crossing there would occur the 80th anniversary of a family tragedy, played out in those very waters.

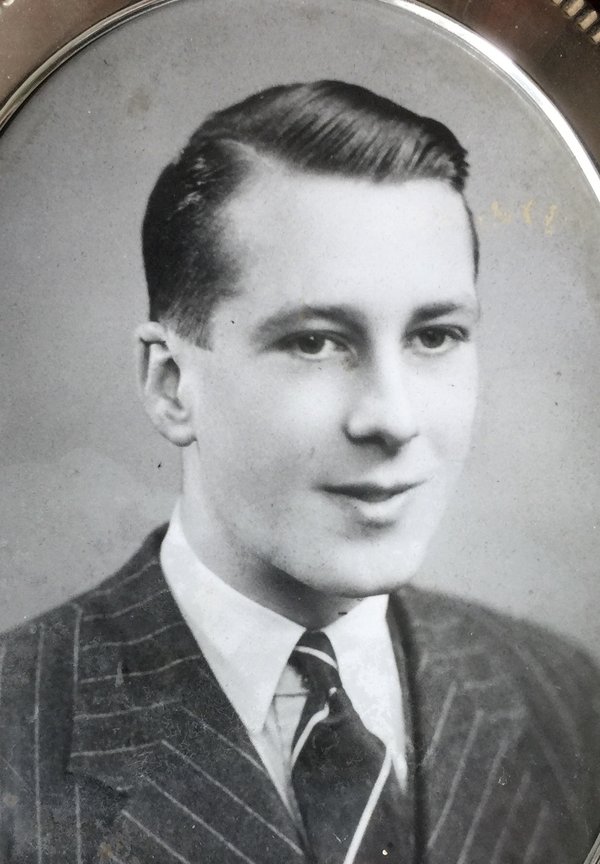

My Uncle Pat – my mother's brother – was serving on a merchant troop ship, the MV Abosso. On the evening of 29 October 1942, when the ship was travelling alone in the North Atlantic, it was torpedoed by a U-boat and sunk. 362 of the 393 passengers and crew lost their lives, including Uncle Pat, who was just 23 and had married only a few weeks before.

Just one lifeboat survived with 31 souls to tell the tale, some of them Navy officers who were aware of the detail of what happened.

The reason for telling this sad tale in an AHS blog is that there were two critical horological elements to the tragedy.

About 6 p.m. that evening, the master of Abosso, Captain Reginald Tate, became aware the ship was being tailed by a U-boat – U575, commanded by Kapitan-Leutnant Gunter Heydemann (1914–1986), as it turned out. The ship's crew was able to detect the submarine using ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) echo-sounding to determine the sub's bearing and distance, the latter by using an ASDIC chronograph.

The watch has a high frequency sweep-seconds hand on a dial recording up to six seconds, the time between transmission of the sound pulse and the echo determining the distance of the sub from the ship.

Having established precisely where the sub was, the ship's master had to decide what to do.

An option was to go full steam ahead and try to out-run the submarine, which would normally be possible – a submerged submarine makes much slower progress, though at a maximum speed of 14.5 knots, the Abosso was not a particularly fast ship.

The alternative was to adopt a 'random' zig-zag course so the U-boat could not predict the ship's position accurately enough to make it worth firing torpedoes at it, though zig-zagging naturally slowed down the progress of the ship considerably. The practice did generally work well, if maintained long enough, as U-boats had limited quantities of fuel and eventually had to head off for a rendezvous for refuelling.

Deciding not to try and out-run, but to zig-zag, the Abosso brought into action its zig-zag clock, a part of the navigational equipment on the bridge of WW2 merchant ships at the time.

A fairly standard ship's bulkhead clock is adapted to have an electrical contact at the tip of the minute hand, and round the periphery of the minute track on the dial is a metal ring with a number of moveable electrical contacts.

Each time the minute hand touches a contact it closes a circuit and a bell rings in the wheelhouse informing the crew to change course one way or the other.

If in convoy with other ships it is of course vital that all the ships adopt precisely the same agreed pattern of zig-zags, and when the instruction to zig-zag is given, the whole convoy would be signalled a secret code for the pattern to be used. The contacts on all the ships’ clocks would then be adjusted accordingly and zig-zagging would begin at a specific time, thus foiling the U-boats' attempts to align torpedoes with a target ship.

The log of U575 has survived, so we can also follow what happened from the U-boat’s perspective. Heydemann, a much decorated Commander in the ‘Brandenburg’ wolfpack in the North Atlantic, sighted the Abosso about 6 p.m. that evening. He was running low on fuel but decided to try and attack. Realising he was being traced, he went deep, out of reach of the ASDIC, but followed from a distance until he was nearly out of fuel. At that point, thinking they had lost the sub, Abosso’s master made the fatal decision to stop zig-zagging. Realising this, Heydemann risked running out of fuel and moved closer to the ship to attack.

Reading the U-boat's log today, and comparing with the U-Boat Commander’s Handbook (available as a translated reprint as E. J. Coates (translator), The U-Boat Commander’s Handbook, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, 1989) one discovers this was a textbook operation.

At 22.13hrs, Berlin time, one of the middle torpedos of four directed at the Abosso in a fan pattern struck the ship virtually amidships. The U-boat surfaced to inspect the target and Heydemann recorded seeing lifeboats being launched. One more torpedo was fired into the ship to deliver the coup de grace, and about half an hour later Abosso sank, U575 then departing to rendezvous for refuelling.

The one lifeboat which survived was picked up on 31 October by HMS Bideford, one of a convoy forming part of 'Operation Torch', heading for North Africa but, in the heavy seas at the time, no other lifeboats or survivors were ever found.

On the evening of 29 October this year, exactly 80 years later, and as close to the location of the Abosso’s sinking as I could estimate, I sneaked a centrepiece flower arrangement from our table after dinner and, against Cunard’s strictest rules, cast them into the sea at the stern of the ship.

A timekeeper had shown Abosso where the danger was, and the other timekeeper should have saved them. It is a sad thought that if only Captain Tate had left his zig-zag clock running just a little longer, the U-boat would have had to leave and 362 lives would not have been lost.

R.I.P. Uncle Pat.

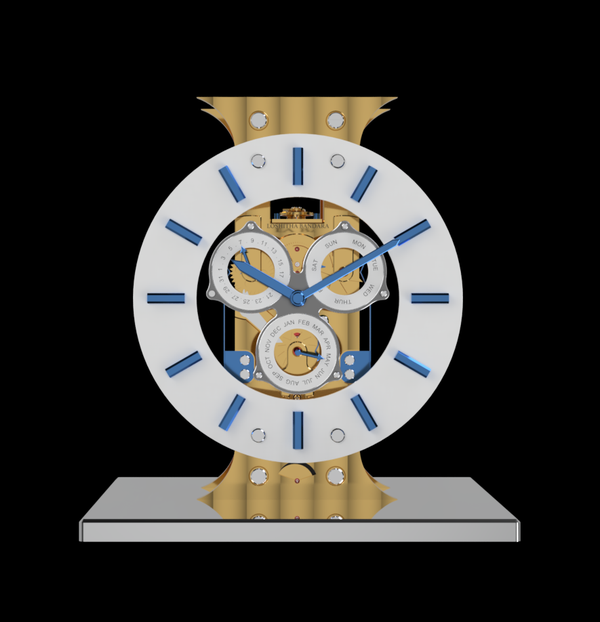

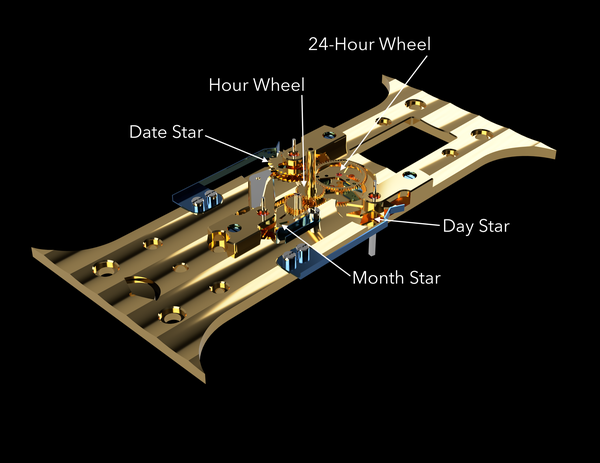

The AHS Birmingham City University Prize 2022

This post was written by James Nye

At the Birmingham City University School of Horology awards evening on 16 June, the AHS BCU Prize was awarded to Loshitha Bandara for his outstanding final-year project, a skeletonised mantel clock with triple calendar and power reserve indication, inspired by F-P Journe and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Many congratulations from the AHS! Winning this award with such an accomplished clock is a clear signal that we should watch out for Loshitha who no doubt has an amazing career ahead of him.

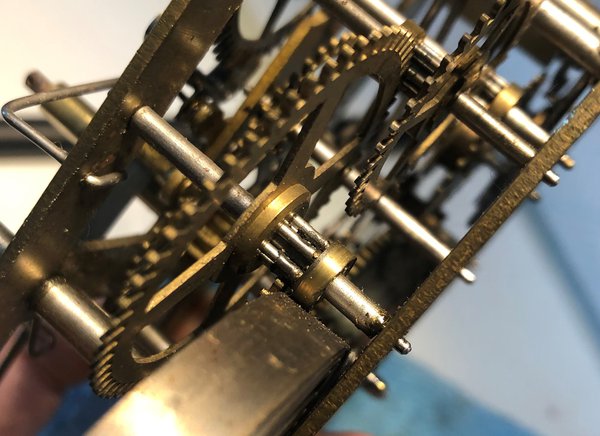

The clock is a tour de force, involving a range of finishes including engine-turning, Geneva stripes, perlage, straight-graining and guilloche.

The Ivanhoe Astrolabe

This post was written by Andrew Miller

Recently I re-discovered (in a drawer) a piece of work that for me is ancient (30 years) but for the type of work is quite new (less than 500 years). It might be of passing interest to members.

It is solid state and largely untroubled by mechanical disturbances. Its accuracy should not deteriorate significantly over the next few hundred years.

It is a 1988 reworking to a smaller scale of an Arsenius astrolabe. Arsenius worked in Holland in the 16th century and is one of the great astrolabe makers. The original would have been a brass instrument some 11" diameter; this is 110mm and made of silver, ebony and copper.

The era has been updated to the current era, whereas many astrolabes are calibrated for an era some 2000 years ago when the fixed stars and constellations were first placed around the ecliptic. This is handy for using the instrument today although astrologers prefer the ancient calibration because the stars are in the 'right' place relative to Sun and planets.

The device was the must-have techno-gadget for cool dudes in the late 1500s. It will show current time and date if you have celestial sightings and the positions of the fixed stars and Sun if you have a time and date.

It will calculate not only the equal and unequal hours (the latter used in medieval times before reliable clocks were widely available) but also the height of tall buildings.

The face of the instrument has the standard rete (web) and rule through which the latitude plate can be observed. Four latitude plates are included inside the instrument and are engraved for five northern latitudes. The reverse has the calendar and zodiac on a 360 degree scale which can be used with the alidade for sighting the altitude of the Sun and fixed stars as well as predicting their altitudes.

Made in 1988 after I had spent some months at sea on the sailing yacht 'Ivanhoe' and had ample time to star-gaze under unpolluted skies. So I call it the Ivanhoe Astrolabe.

Inspiring people with horological collections: a guide’s perspective

This post was written by Robert Lamb

Since October 2015, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection of clocks, watches and associated objects has been displayed in its new home at the Science Museum, where it is accessible to the public whenever the Museum is open.

I have been conducting 60-minute tours of this wonderful historic collection on a monthly basis since July 2019. Despite needing to pause during the pandemic when the museum was closed, myself and the other volunteer guides have been back up-and-running since October 2021 and we hope that the frequency of the tours will increase as more volunteers join the team.

So, what happens on my tours?

Firstly, I introduce myself to the group and enquire if anyone has any specific interests. Participants are a pretty eclectic mix of those who, by chance, saw the notice at reception, those who came especially to see the collection, inquisitive tourists, and passers-by who show an interest and I cajole to join!

I then explain that we will not cover the whole collection, but will be honing-in on specific objects and groupings or significant topics and people.

I always like to give a short introduction to cover the origins of the collections, history of clockmaking and development of London’s Livery Companies.

Having gauged the mood and interest of the group (not forgetting that children may need entertaining too!), we often start with the introduction of domestic clocks in Europe and London, followed by the later need for more accurate timekeeping. Often, we look at the introduction of the pendulum and I talk about the development of clocks in London with the knowledge brought back by John Fromanteel. We are regularly drawn to John Harrison and his fight for recognition to win the Longitude Prize and then become fixated by H5!

There are so many tales to tell of the many objects we encounter. I love the one of an early Master of the Company, whose role was to keep the Company chest (which contained the silver and significant documents) at home during his tenure, but couldn’t get it through his front door!

No two tours are ever the same, which gives me great pleasure and I hope it does this for the participants.

Joining a tour is the only way to see what actually happens – visit the fabulous collection yourself and soak up the wonders of such a diverse horological history!

A prize-winning project 2021

This post was written by Iolanda Clopotel

My name is Iolanda Clopotel, and I have recently completed my degree in Horology studied at BCU in the School of Jewellery.

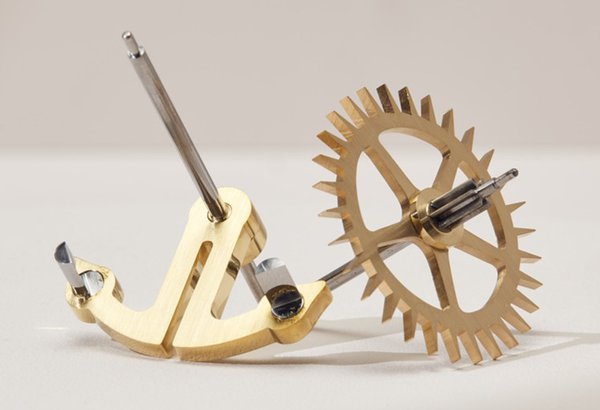

Our last and major task within the course was designing and manufacturing, from stock, a clock of our own design. This project allowed us to explore and put in practice the knowledge and skills learned in the previous years, and I have chosen to make a clock inspired by the French drum movements, featuring a Brocot escapement.

Learning more about the design of this escapement was a wonderful experience, and I am happy to have succeeded in making a working escapement by the end of the course, both in reality and in the virtual environment.

I was lucky enough to achieve the highest scoring marks in my year group and I would like to thank LVMH Watches and Jewellery for the wonderful prize in the form of a beautiful chronograph that I will wear with pride from now on, as a reminder of my own achievements.

I would also like to thank the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers for their award which will be very useful in completing future and on-going projects.

I feel grateful for the people and companies that support and reward new horologists that are just entering the field and help in keeping the passion for always improving the craft skills of precise timekeeping.

Stinky horology

This post was written by Tabea Rude

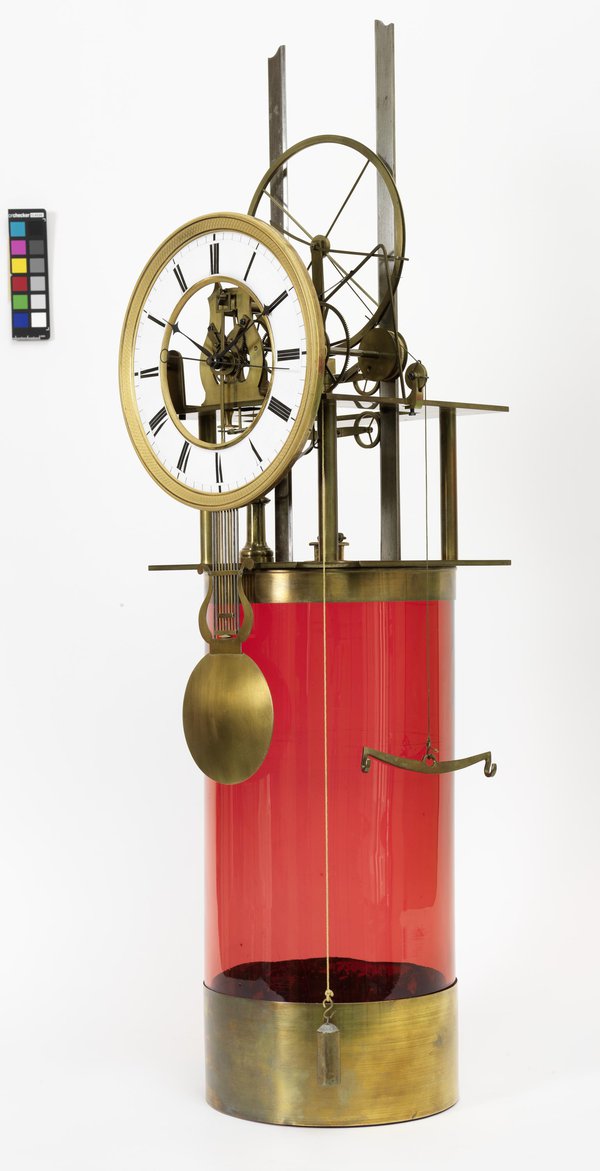

Not many clocks can claim a major olfactory experience by nature of their operation, but this one must have done: the hydrogen clock by Pasquale Anderwalt (1806-1881).

It is mentioned from the early 1840s onwards in several German publications. Anderwalt was a mechanical engineer and worked in Trieste. He developed machines for agricultural use and received a privilege for improvements on windmills. In the 1850s, he was involved in finding and proposing solutions for the frequent shortages of drinking water in Trieste.

For that reason, he was sent to the 1851 World Exhibition in London, to find out what the department of hydraulics and the gathered experts from all over the world had to offer. He also brought his hydrogen clock for presentation. Quite a number of these curious hydrogen clocks survived. Some readers may have seen one of these on display in the Clockmakers Company Collection at theScience Museum. Another is found in the Vienna Clock Museum, with three further examples in museum storage in Vienna and Trieste.

All of them have this rough idea in common: The glass cylinder is filled with sulphuric acid, the owner adds zinc and closes the lid. The zinc then reacts with the sulphuric acid to hydrogen, pushing a piston upwards, which in turn rewinds the weight.

Anderwalt himself claims that 'one ounce of zinc will last the clock machine at least for a human life span'. Probably a very trendy machine in its time, it could definitely compete with other alternative power ideas and not-so-perpetual-motion-clocks. Articles about these have been published in a number of Austrian, Moravian, Italian as well as Bavarian newspapers and scientific reviews. It is not known how many of these objects exploded during use or how smelly they really were.

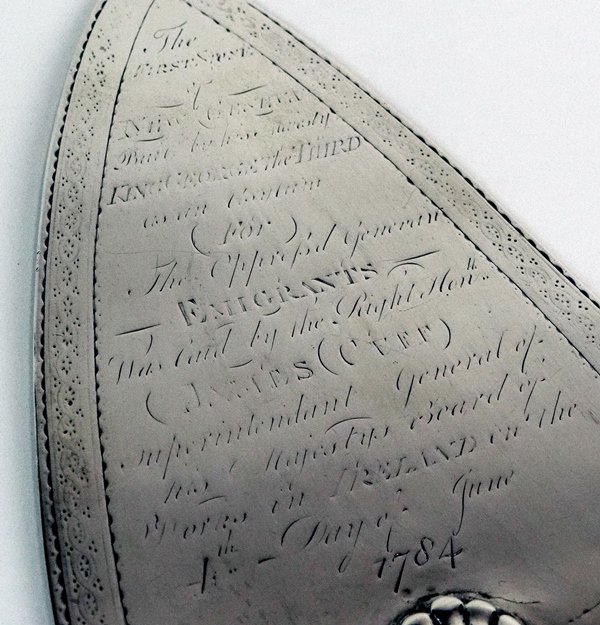

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

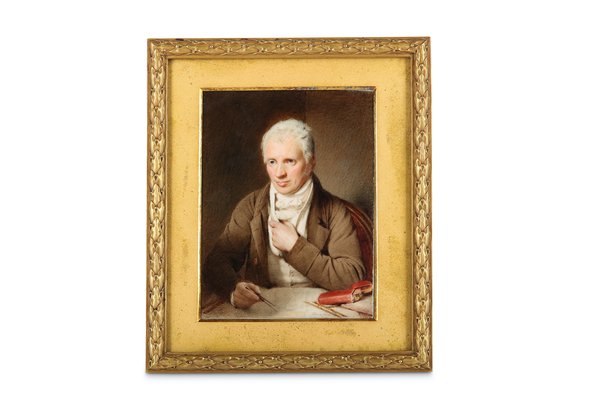

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

Stories of an everyday timepiece

This post was written by Andrew Hyatt

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. One of the things that interest me in horology as a student are the stories that timepieces can tell. Whilst the world changing events of John Harrison’s H1 through to H5 or the exciting life of Larcum Kendall’s K2 do make for fascinating reading, I am talking about the story every timepiece that I hope to end up servicing will tell me.

This story is not necessarily the emotional attachment that the owner undoubtedly has to the item. That can be interesting, but in taking apart one of my first clocks I found what I consider to be a much more interesting story.

The clock shown below is a mass produced 2 train clock with a rack striking mechanism. I picked it up because I loved the art-deco style case and the unusually shaped dial.

It is clear that several other people also did as when I took the movement apart my initial observations found a couple of things, the first is that at some point the pendulum suspension spring has been replaced. Both the rod and the back cock have been bent to accommodate a new plastic topped spring shown below.

This made me a little worried about the rest of the mechanism with what appeared to be a quick fix to get the clock running again, but as I continued I found evidence of what may have been a more caring hand. The back cock also shows evidence of the escapement/crutch arbor pivot hole having been re-bushed with the finish almost invisible on the acting face. One of the click springs has also partially sheared, but then its been re-blued.

This tells the story of one or more people that got this clock running again and I am excited to add my name to that list, hopefully in a less noticeable way, as this clock continues its story.

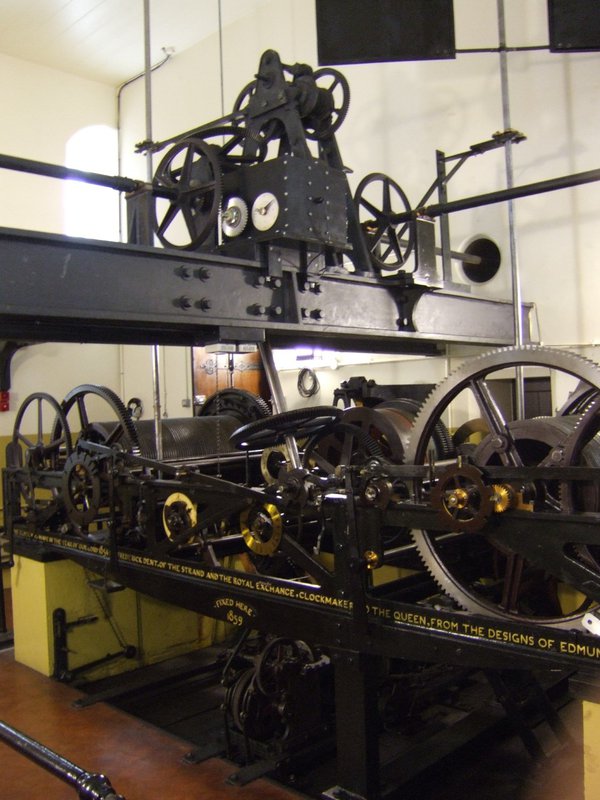

Elizabeth Tower from construction to conservation

This post was written by Jane Desborough

On a cold, dark evening recently my spirits were lifted when I had the pleasure of listening to an online lecture on the conservation work that has been undertaken on the Elizabeth Tower at Westminster.

Presented by tour guide, Catherine, who is clearly very experienced in talking about the Tower, the clock and the bells, it was a really engaging and accessible gallop through the history and overview of the recent conservation works.

For fans of horology, there were no big surprises – most people know the story about the cracked bells and the key players ( Edmund Beckett Denison, Sir George Airy, Edward John Dent and Frederick Dent) involved in the design and making of the clock – but a couple of points stood out for me.

The first was the discovery that when the clock was finished in 1854, it had to wait for the rest of the tower to be complete before it could begin its public service – this was five years later in 1859.

The idea of a paused instrument – one that’s designed to move continuously – made me think that there must have been a lot of work needed to store it safely, maintain it in good condition and to set it going five years after its production. It was interesting to hear that those five years provided some time for experimentation with the escapement.

Another fascinating aspect of the talk was centred on the lamps required to light the dials at night. Recent conservation work has replaced all of the lamps with LEDs.

As a more efficient lamp, the LED will obviously be a good energy-saver. The change makes sense, but I couldn’t help being pleasantly surprised that the same changes being made at a small, household scale are also being made on a larger scale with our public buildings.

For me this talk was great because you can think you know a clock or a building, but there’s always something new to discover!

Opening my first clock

This post was written by Alexandra Verejanu

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. In the context of the lockdown I got pretty behind in my studies as we couldn’t go into the workshop. As I knew it would be helpful to see and touch a mechanism, I decided to buy some cheap old clocks. The clock I have 'played' with brought some interesting questions to my attention.

Firstly, I couldn’t take it out of the case, probably because it didn't seem to have been made to be serviced. I might have stumbled upon one of those old American clocks which were made to look fashionable in the house, but after a few years were discarded as uneconomical to repair. .

I looked closely and it was obvious someone has taken it out of its glued case using some aggressive methods, like bending the bell rod and cutting holes in the case. After two hours of struggling to carefully remove the mechanism from the case, I bent the bell rod and took it out.

Then, I examined the mechanism which was very oily. I knew excessive lubrication can do more harm than good, but I didn’t expect to see damage with the naked eye.

In the future I intend to change the damaged pieces, hopefully with some I will produce in the school workshop.

I decided not to take apart the mechanism just yet, as it was useful as a comparative item to the clocks I was presented with during online courses.

Considering this timepiece is not in its best shape, I might try to do some case work during the summer. I will not be able to fix the cuttings, but I’ll give it a good clean and maybe turn the case into an easy to open one.

This clock was very helpful during lockdown and helped me understand the mechanics of a clock. It truly helped me connect and mesh information from various sources which I was not able to understand.

Special thanks to my teacher Mathew Porton, for taking his time to answer all my questions and making sure I will be safe when I disassemble the mechanism and work on it.

A bad time in Znojmo

This post was written by James Nye

In my January 2021 London Lecture on Johann Antel (1866–1930), the Czech/German clockmaker (available to AHS members here), I condensed much, and stories were omitted, like this one–a disastrous episode.

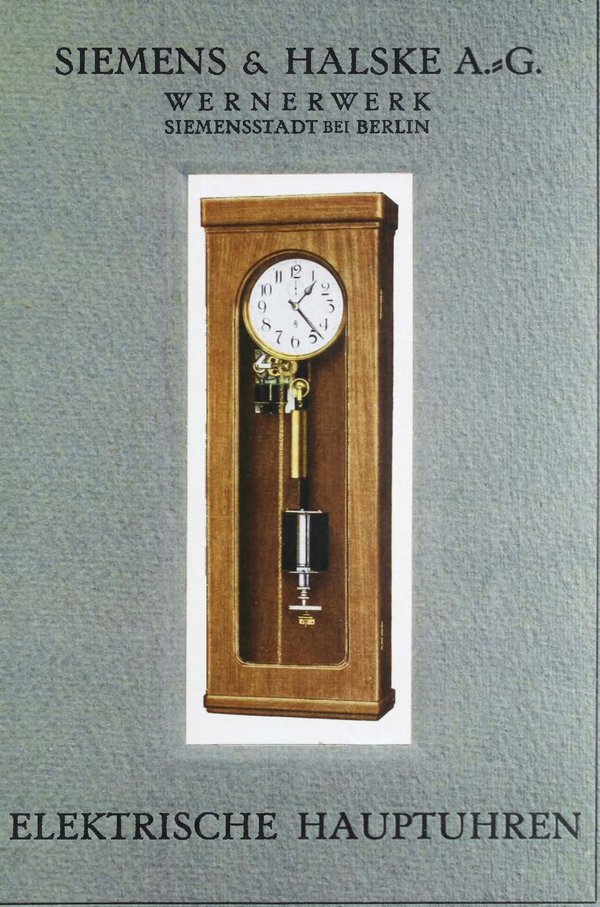

In 1930, the Znojmo authorities sought quotations for a clock for the bus-stop in Divišovo Square. Antel himself died that July, but his firm won the tender, offering a four-sided rooftop subsidiary clock, driven by a minute-impulse transmitter clock. Antel would source it from Siemens and Halske of Berlin, or its Prague subsidiary Elektrotechna.

Installation started in February 1931. In lifting the clock housing onto the bus-stop roof, the ladder slipped and both technician and clock fell to the pavement. Six weeks were lost in repairs. It was finally installed 24 March 1931. But regular attendance by the technicians over the next month suggests all was not right from the beginning.

Antel’s widow Ludmilla issued proceedings to secure payment, but matters dragged into 1932. The legal papers are actually a wonderful source of information on this catastrophic installation. The original drawings showed dials with numerals, but Antel’s firm delivered a clock with four plain dials, claiming they looked more ‘modern’.

No! said the town, we want numbers!

They also wanted a thicker gauge of glass, as the night-time illumination revealed too much of the motion-works, and the lamps were so bright the hands were invisible. A hand went missing, perhaps the fault of the technician who upgraded the glass.

In July 1933, the local paper Nas Týden reported all four dials showed a different time. A satirical piece followed in Ochrana in October, urging civic pride in a clock that showed different times on different dials, like the astronomical clock at Olomouc.

The gods never favoured the clock, and it was probably replaced in around 1938. As with an ill-fated earlier installation at the law-courts, Antel never had much luck in Znojmo.

The unexpected visitor

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Almost exactly ten years ago I had John Harrison’s magnificent first marine timekeeper H1 in my workshop at the Royal Observatory. It was being dismantled for study, cataloguing and conservation for the new chronometer catalogue.

I had a film crew with me making a documentary, and they were becoming exasperated at constant interruptions to the filming. Finally another telephone call – a man was outside, asking if he could see me. Embarrassed, I assured the film team I would politely ask him to come back another time, but explained they had to come with me as I couldn’t leave them alone with H1.

Outside, the man apologised for arriving without warning and that he could come back if necessary. He introduced himself, offering his hand and just saying softly “Neil Armstrong”.

One of the film crew laughed and remarked 'Ha! I bet with a name like that you get lots of requests for autographs!' to which the unassuming gent simply replied: 'I’m afraid I don’t do autographs'.

It was at that point that we collectively realised that we were indeed in the presence of history. Suffice to say, all anxieties about filming schedules melted away and we all returned to the workshop (but with film cameras firmly switched off!)

Armstrong had long been a Harrison fan and he and his golfing friend Jim, hearing on the grapevine about the H1 research, had taken a detour from a sporting trip to Scotland, to make a pilgrimage to Greenwich.

For a wonderful hour or so we discussed Harrison and his first pioneering longitude timekeeper and it was clear Armstrong’s reputation was correct – reserved, yet of great intelligence and hugely well-informed; in short, a thoroughly nice man and not at all the showman one imagines when thinking of lunar astronauts.

I always asked visitors to sign my Visitors Book, but understood when Armstrong explained 'if you don’t mind, I’ll do it in capitals'.

Hearing that Harrison’s second prototype timekeeper, H2, would be next for research in the coming year, Armstrong returned and I spent a little more time with him, getting to know him a little better and was privileged to learn more of the Apollo 11 mission, from the horse’s mouth, as it were.

As he and Jim left on that occasion I asked Jim to sign my book again, and as they got back into their car, Jim whispered to me 'I think you’ll find Neil signed properly this time too'.

And indeed he had, something I shall always treasure.

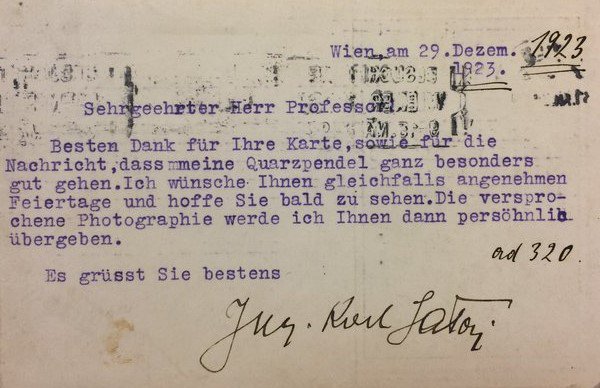

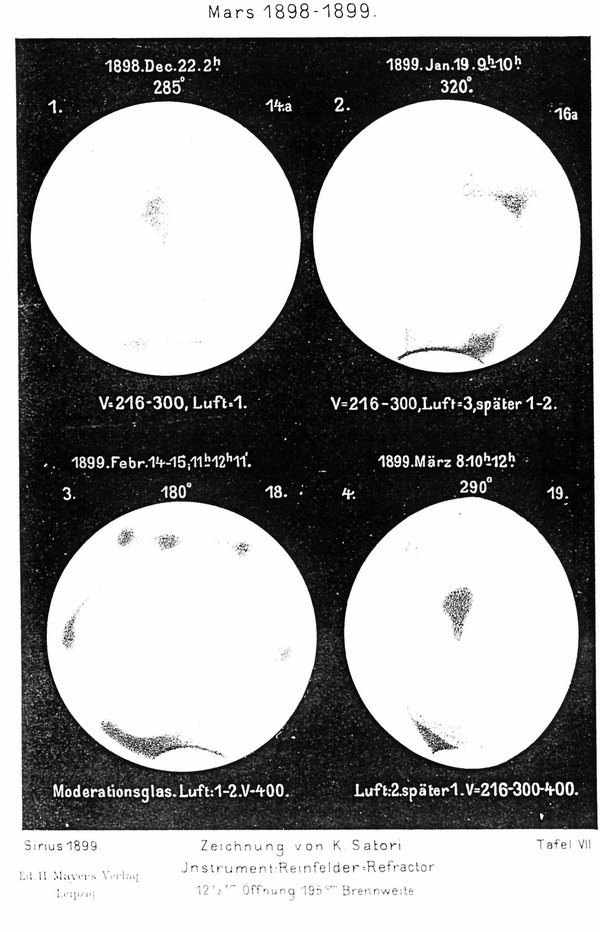

Mr Satori fuses quartz

This post was written by Tabea Rude, Vienna Museum

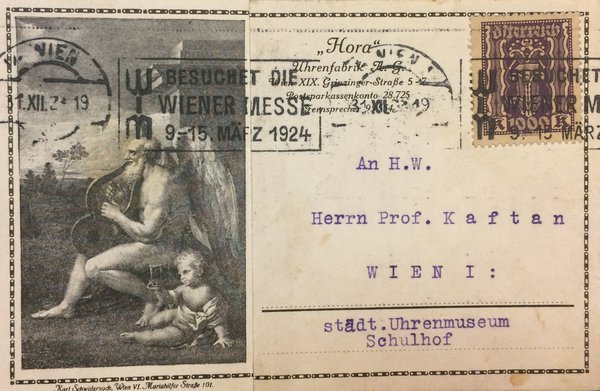

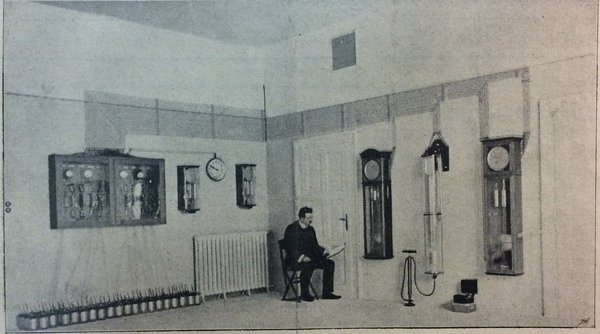

Around one hundred years ago, on May 15th 1918, the newly founded, not yet opened Vienna clock museum receives a generous present: a clock movement fitted with a fused Quartz pendulum rod.

It is installed in a most prominent position: right next to the entrance, in a case with a fully glazed front. Visible to every passer-by, it draws attention to the narrow house with its hidden treasures in the heart of Vienna.

This donation was the beginning of a long lasting correspondence between the clock museum’s director Rudolf Kaftan and the engineer, donor and inventor Karl Satori.

Originally from Hungary, Karl Satori is first mentioned in the proceedings of the international electrical society (Internationale Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft) in Vienna aged 24, explaining Lorentz electron theory.

In the following years he delves into astronomical observation and planetary documentation and builds up professional relationships in the astronomy scene.

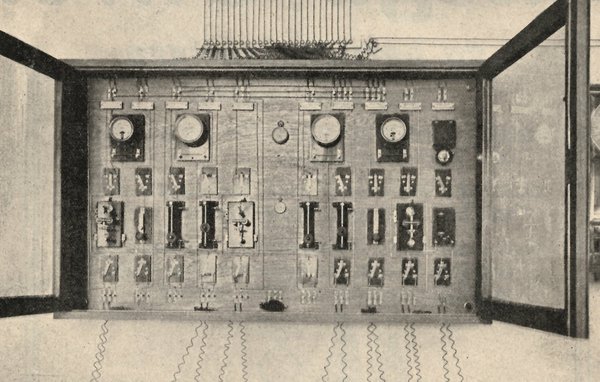

Soon he joins the international astronomical society and files his first patent in 1903: an electrical rewind system for clocks.

His professional career blossoms, allowing him to invest in his own private observatory in Vienna.

Around the same time, he is also given the opportunity by the Vienna electricity works to build up his own laboratory and to equip the Viennese Urania observatory with an electric time system which synchronized all public clocks in Vienna. This supplies the time signal as so called ‘Urania-Zeit’ to all telephone owners.

Besides his involvement in astronomy and several other clock related patents, he was also very keen in exploring pendulum materials and different methods of air pressure and temperature compensation.

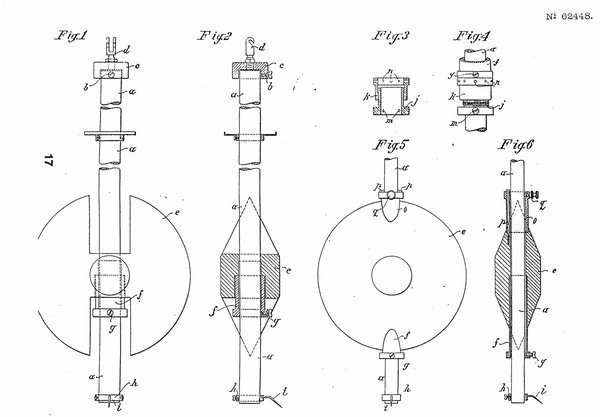

Recognizing the unfortunate jumps steel pendulum rods experience during temperature changes and their reaction to magnetic fields, he experiments with fusing quartz into seconds pendulum rods. In 1912 he files his patent of the quartz pendulum.

One year later he opens his own precision workshop for mechanics and clock making. Satori expands, fuses quartz, files patents and ensures that the Vienna clock museum is placed to show the most cutting edge Viennese horological technology of its time.

Two-timing

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The dictionary defines ‘two-timing’ as ‘to be unfaithful to a spouse or lover’ or ‘to deceive, to double-cross’. But that’s not what I want to talk about. What I have in mind here is people who put the clock forward even though they know it’s not the ‘real’ time. Perhaps we can regard this as another kind of cheating.

Some months ago I came across the term ‘Sandringham time’. British Summer Time – putting the clocks forward one hour in April and back again in October – was introduced in 1916, and among those supporting the idea had been King Edward VII (1901-1910).

Here (with thanks to David Rooney who supplied me with a scan of the relevant page) is what David Prerau wrote in his book Saving the Daylight: Why We Put the Clocks Forward (page 12):

'The king had recognized the waste of morning daylight and had already taken royal action: for several years, in order to have more time for hunting, he had been creating his own small sphere of daylight saving time at his palace at Sandringham, and in later years at Windsor and Balmoral castles, by having all the clocks advanced thirty minutes. (The tradition of ‘Sandringham time’ lasted until Edward VIII abandoned the practice in 1936).'

I was reminded of this when this week I finally got around to reading Flora Thompson, Lark Rise to Candleford , a semi-autobiographical series of three books giving scenes from a childhood in rural Oxfordshire in the 1880s and 1890s.

The books were originally published in 1939, 1941 and 1943, and then as a trilogy from 1945 onwards. I quote from the Penguin Modern Classics edition of 2008.

At the age of 14, the main character Laura (Flora) starts work as assistant in a Post Office. It is run by a woman, Dorcas Lane, alongside a blacksmith’s workshop which she had inherited from her father.

'The grandfather’s clock was kept exactly half an hour fast, as it had always been, and by its time, the household rose at six, breakfasted at seven and dined at noon; while mails were despatched and telegrams timed by the new Post Office clock, which showed correct Greenwich time, received by wire at ten o’clock every morning' (page 364).

The Post Office is re-introduced at the beginning of Part 3:

'As she followed her new employer through the little office and out to the big front living kitchen, the hands of the grandfather’s clock pointed to a quarter to four. It was really only a quarter past three and the Post Office clock gave that time exactly, but the house clocks were purposely kept half an hour fast and meals and other domestic matters were timed by them.

'To keep thus ahead of time was an old custom in many country families which was probably instituted to ensure the early rising of man and maid in the days when five or even four o’clock was not thought an unreasonably early hour at which to begin the day’s work.

'The smiths still began work at six and Zillah, the maid, was downstairs before seven, by which time Miss Lane and, later, Laura, was also up and sorting the mail' (pp 395-6).

In the first volume, when Laura is still a small child living with her family in a nearby hamlet, we find another interesting example of dual timekeeping.

One person in the hamlet, ‘Old Sally’, owned 'a grandfather’s clock that not only told the time, but the day of the week as well. It had even once told the changes of the moon; but the works belonging to that part had stopped and only the fat, full face, painted with eyes, nose and mouth, looked out from the square where the four quarters should have rotated.

'The clock portion kept such good time that half the hamlet set its own clocks by it. The other half preferred to follow the hooter at the brewery in the market town, which could be heard when the wind was in the right quarter. So there were two times in the hamlet and people would say when asking the hour: "Is that hooter time, or Old Sally’s?"' (p. 77)

The popularity of horological tattoos

This post was written by Anna-Rose Kirk

Clocks and watches are the most tattooed image at the moment according to Vice magazine, and tattoo artists are sick of tattooing them.

'Clocks. Clocks, pocket watches and more clocks . Mostly on guys in their mid 20s. There must be hundreds, at the very least, being done in the UK every week. Lots of tattooists have stopped putting them in their portfolios because they’re so fed up with them' (Craig Hicks).

Time symbols have always been popular in art as reminders of the passing of life and the inevitability of death.

Hour glass tattoos have been a simple depiction of this for many years, and there has been a long tradition of symbolism within prison tattoos depicting clock and watches with no hands. However, the more recent need to capture time has sparked a trend of more complicated depictions and designs within larger tattoos often surrounded by banners, flowers, and owls.

Speaking to those that have the clock or watch tattoos, it is apparent that the most common reason was the idea of symbolising a date and time, a child’s birth for example, and was a way of avoiding text and numbers which have become a common tattoo choice.

Others wanted them as reminders that time is precious and had them tattooed in prominent places as a constant reminder to live their lives meaningfully.

One person I spoke to simply had a deep appreciation for horology and the way that watches worked after coming across them in his job in a jeweller’s and from his friends in the industry. Because of this, the time on the watch does not have a significant meaning, but it was important to him that the detail and the way it looked was right.

Celebrities and easy access to images and discussions play a part in tattoo trends but simply more people are getting tattooed meaning particular images seem to get used more often.

I wanted to get to the bottom of whether clocks and watches were seen as something mysterious with no concept of the inside workings, however, although a lot of the general public, especially the younger generation, does not understand the exact mechanics of a pocket watch, they have a tangible feel which in contrast to today’s sleek, minimal, computerised technology can feel a lot more real. They feel as if the have a history and a story; linked to memories tradition and ritual.

I wonder if a rise in nostalgia and a romanticism for craftsmanship and the handmade has brought about the rise of this style being used in tattooing and movements like Steam Punk.

It is perhaps a fight against excessive consumption of the 21st century and the dehumanisation of manufacturing and the idea that traditional skills may be lost. It seems to be that horology is being worn as a symbol of authenticity and a preservation of history in a vain attempt to show that this generation care.