The AHS Blog

The second edition of 'Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping'

This post was written by Charles Ormrod

Robert Miles’s landmark work, Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping , sold out a few years after its original publication in 2011. Since then, copies of this highly sought-after book have been selling for several times the original cover price of £50.

The AHS is therefore delighted to announce that a long-awaited second edition is now available, made to the same standards as the first, hard-backed and thread-bound, at a new low price of just £25 plus postage.

As a humble labourer in the vineyard of the second edition, assisting James Nye with administrative work but certainly not with Synchronome expertise, I’ve had a first-class opportunity to learn about the pitfalls of editing, proof-reading, and the finer points of book production.

The possibility of a second edition was mooted some years ago, and revisions to the first edition had been contributed by Bob Miles himself, Derek Bird, Norman Heckenberg, Arthur Mitchell and others.

One of my first jobs was to combine these various sets of revisions into one document, eventually about eight A4 pages long, for presentation to the designer of the first edition, Phil Carr. Phil very generously made no charge for all the work of entering revisions into a new version of the original book’s electronic file.

Double-checking the changes and exploring disagreements between contributors led to many absorbing hours searching for clarification. I now know far more than I did about the history of sonar and the extent to which Second-World-War sonar sound-pulses fell within an audible range (which depended on whether the listener was a fit young sailor or an old sea dog).

I also learned about the Doppler effect on the sound of swinging tower-clock bells, the problems of reproducing the appearance of pre-war electrical flex, alternative cabinet-making methods applied to Synchronome cases, and the best method of setting up the suspension of a Synchronome pendulum.

I must admit I hadn’t quite realised that high-quality hard-backed books, such as the first and second editions of Synchronome, really are still made by sewing groups of double pages together with thread. A machine does the sewing of course, but the principle is broadly the same as with the earliest surviving bound books of the eighth century.

A thread-bound book is much easier to use than a glued paperback because the pages naturally fall flat when the book is opened, and thread-binding lasts far longer.

This second edition of Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping is dedicated to the memory of its author, who died earlier this year in the knowledge that work on a new edition was under way. The book is available to order on the AHS website via this link.

A gala for Lisa

This post was written by James Nye

Tuesday 25 October 2016: to the Victoria and Albert Museum for a fabulous evening to celebrate the life of our late President, Lisa Jardine FRSA, in the company of her husband John Hare, members of the family, and a distinguished array of academics, curators, writers, and lots of friends. It was a year to the date since Lisa’s death.

Lisa believed in lectures that were also a bit of a party. We gathered in the Whiteley Silver Gallery to the sound of a jazz trio, and moved to the astonishing Gorvy Lecture Theatre, where we were greeted by Bill Sherman of the V&A, a colleague of Lisa’s over many years.

He introduced Amanda Vickery, who spoke movingly of her long and close association with Lisa, before introducing the remarkable Deborah Harkness, prize-winning historian and now best-selling author, noted for the All Souls fictional trilogy.

She spoke on ‘Fiction in the Archives’, explaining how a parallel career in fiction has enriched her historical work, following an approach she believes Lisa enshrined – not so much ‘outreach’ – more the invitation to everyone to come and spend time inside the ivory tower.

The spine-tingling thrill of archival discovery is accessible and communicable to all—and truth can be more remarkable than fiction. Setting action in her scholarly backyard—sixteenth century Blackfriars—Deborah told us that ‘Fiction at last allows me to tell people what I really think happened, rather than what I can prove.’

It was a tour de force—resolving to the notion that literature can work to promote empathy, a characteristic in short supply in conflicts at all levels, globally. Deborah’s tribute linked this to Lisa, who championed diversity, bringing together so many people, across so many communities.

John rounded off proceedings by announcing the launch of a new initiative with the Royal Society—the Lisa Jardine Research Awards—essentially funding to encourage the study of the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment, an initiative for which significant backing has already been secured. A very fitting tribute indeed.

The evening wound up with a reception in the galleries housing the Ionides collection, to the sound of more jazz. Our hosts were generous, but were probably mindful of Lisa’s mantra—‘never knowingly undercater’—it was a magical event.

A supplementary (late) meeting report (from 1957)

This post was written by James Nye

Petrol rationing ceased in May 1957, but the legendary Colonel Quill, DSO, had long planned the AHS September visit with a view to everyone needing to use public transport, staying local in London.

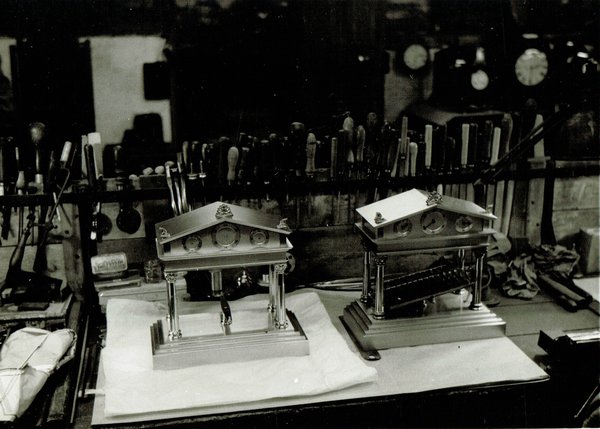

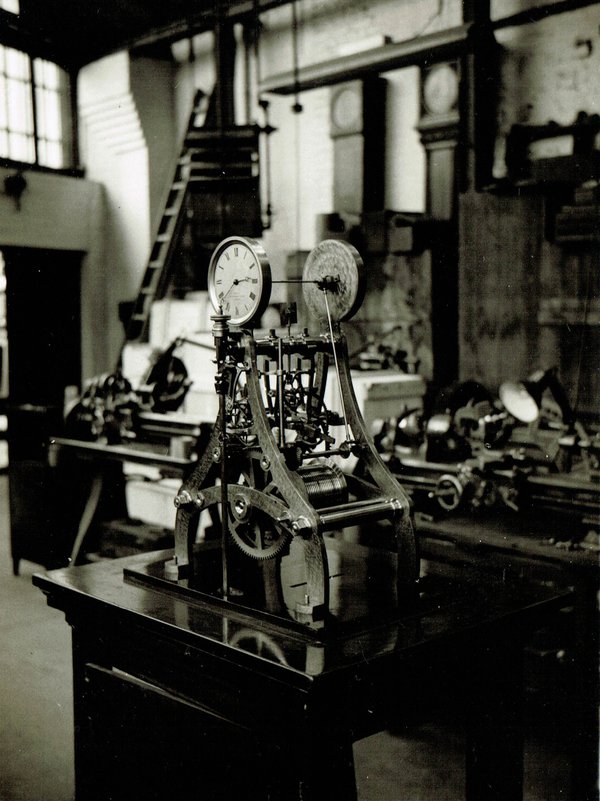

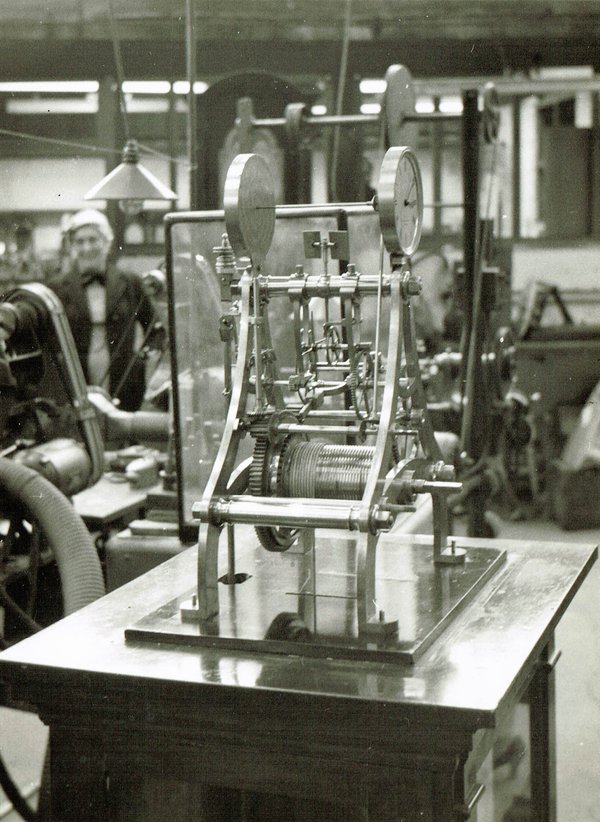

About forty members and friends descended on the workshops of E. J. Dent & Co in Lambeth, but the meeting report (AH Dec 1957, p. 95) was text only.

On the day, pictures were taken by our distinguished early member Bob Miles, but not being used these found their way into an envelope, to disappear in our archive, until I had a look inside, nearly sixty years later, a few days ago. I thought it was high time they had some exposure.

Daniel Buckney (great grandson of E.J Dent) and AHS founder member Charles Williams, both of Dent, showed everyone round.

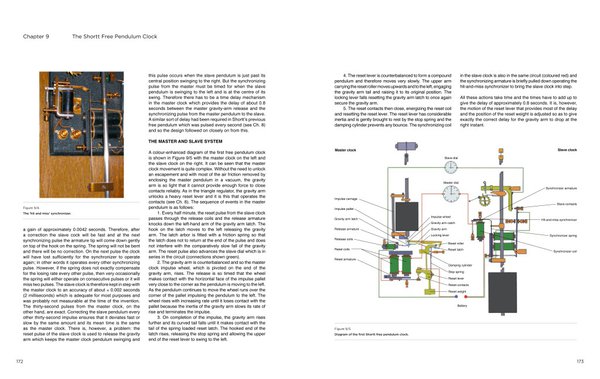

The objects on view ranged from a striking wrought iron cage clock by Edmund Howard of Chelsea (1761), through to modern editions of the Congreve rolling ball clock, a design which continued to be made for several more decades.

In the case of the Howard, substantial information has come to light in recent days, and I will try to resolve this into an article for the journal as soon as possible.

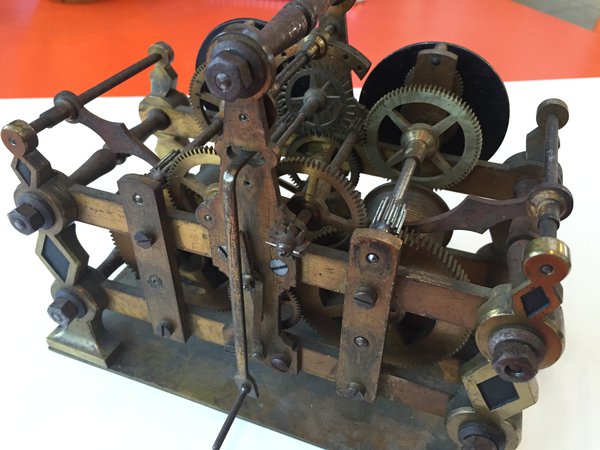

Being Dents’ workshop, there were turret clocks aplenty, of course, including examples not only from Dent, but Benson, of a wide variety of shapes and sizes.

An unusual and quite large 1939 Dent quarter-striking gravity escapement clock sported intriguing fans mounted either end, and within the frame, pivoted horizontally at right-angles to the train.

It had a most unusual gravity escapement, with the escape wheel formed in the shape of a hexagram. It later found its way to the Science Museum, where it still resides.

A wonderful exhibition model turret/skeleton clock was on display, which later found its way to the Rockford Time Museum, and thence to a fabulous private collection. A British Pathé film taken in the workshops only a short time later features many of the same clocks.

The joys opening old envelopes can bring!

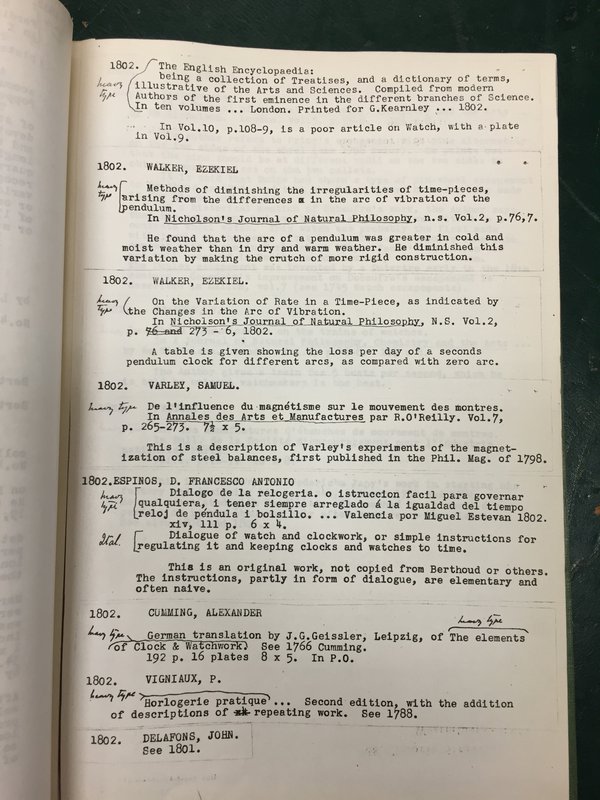

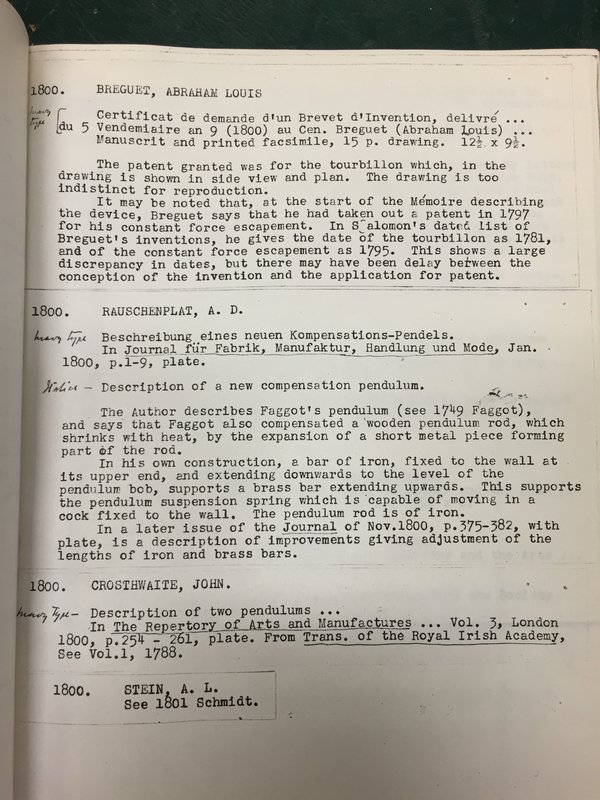

Better late than never – Baillie Bibliography Vol 2

This post was written by James Nye

Someone I know is researching the electric clock systems of Ritchie. Being a pro, I rather suspect they have run a lot of obscure sources to earth, but I’m going to make a point of drawing their attention to English Mechanic and World of Science from 1874, where I believe Ritchie published a piece on controlling clocks and time-signals by electricity.

This might come as an interesting addition to the better known 1878 piece in the Journal of the Society of Arts (vol. 26).

Another friend has a forthcoming piece on the pneumatic time distribution systems of Mayrhofer, which will appear in the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie’s next yearbook. There is just a chance he may not have come across the 1882 piece by Berly in the Journal of the Society of Arts, providing an overview of the state of the art in pneumatic horology.

How on earth do I come to know of these possibly useful references? In 1951, G.H. Baillie published an historical bibliography, covering horological literature published prior to 1800. It has been a goldmine ever since.

A second volume, covering literature published between 1800 and 1899, was drafted, but never published – until now. The AHS has arranged the copy-typing of the typescript, and a digital (searchable) version is now available to download from the members’ area of the website.

It’s a fantastic new resource for researchers. Yes, all the obvious literature is there, of course, but there are also vast numbers of obscure references which will illuminate your research.

And Baillie included the good, the bad and the ugly.

An 1889 article on watch cocks by Luthmer is described simply – ‘the illustrations are very good. The text is of little value’. Parker-Rhodes’ 1885 pamphlet on ‘Universal Reading of Time; is ‘of no value or interest’.

But Baillie is unstinting in his praise where it is merited – witness the simple observation on Poppe’s 1801 Ausführliche Geschichte der theoretisch~praktischen Uhrmacherkunst , that ‘this is by far the best history of horology that has ever been written. Hardly a statement is made without a full reference to the authority for it.’

Membership of the AHS brings you full digital access to over sixty years of Antiquarian Horology , and other amazing digitized records – such as this latest bibliography, which finally makes an appearance sixty-five years after the author’s death. It is worth investigating.

Time from the mains

This post was written by James Nye

In 1931, Wireless World published a powerful pictorial depiction of timekeeping from the electric mains. Today, we check the time on our smartphones and glance at standalone battery-driven quartz clocks on walls at home and at work, and it would be easy to assume that time from the mains had been consigned to history.

But look around. On countless supermarkets, town halls, churches and other public buildings the clocks you see run from the AC mains and take their time from the frequency of the UK’s national grid.

These are synchronous motor clocks, running at a speed dictated by the grid’s frequency. To work as clocks, that frequency needs to remain very close to 50Hz. If the frequency drifts, engineers steer it back, avoiding cumulative clock error.

The UK’s Grid Code specifies that National Grid must control the frequency so that clock time remains within plus or minus 10 seconds per day. Thus while synchronous clocks might display an error of up to 10 seconds within a 24-hour period, in practice the error will daily be brought to zero by the 7.00am handover of shifts at the National Grid’s Control Centre in rural Berkshire.

On 11 June 2016, a few enthusiasts from the AHS Electrical Group were granted rare and privileged access to the Control Centre to hear at first hand from its highly experienced and knowledgeable engineers how they handle not only the management of the grid in real time but also how they predict what the load will be a few hours in the future.

Two concerns drive the never-ending work of the engineers: security of supply and efficiency.

Keeping the lights on is paramount but once that is assured, market mechanisms are used to allocate resources.

Reserve power is expensive, so cannot be contracted lightly. Unpredictable supply from renewable sources causes massive headaches. Inertia – enough mass in the form of spinning metal in the turbines connected to the grid – is vital to smooth volatile flows of power.

Grid time was seven seconds slow on our arrival and four seconds slow on our departure – a few hours later after an enlightening and highly informative tour packed with rich detail delivered with confidence from our expert guides.

That our synchronous clocks perform so well is no longer a mystery, given the phenomenal technical and intellectual effort deployed 24/7 to keep the lights on – and to keep those clocks on time.

Mannheim, April 2016

This post was written by James Nye

Friday 15 April 2016 – to Mannheim Seckenheim for the 17th annual electric clock fair, organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven, the chairman of the DGC’s Electrical Horology Group.

This has long become an essential part of the social calendar of Euro-electro-horology, bringing as usual visitors from the UK, Switzerland, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany.

The fair coincided with a remarkable exhibition mounted by Hans Baumann, showing part of his extensive collection of electric watches, showcased in his two-volume publication from 2013.

Several hundred watches were on show, from electro-magnetically maintained balances, through tuning fork examples, onward to early quartz.

The international crew enjoyed themselves with two excellent evening meals, and a visit to the Carl Benz museum in Ladenburg.

In between times, a lot of objects changed hands – on the principle that much collecting involves storing objects for a number of years, and then passing the job of storage to the next collector.

As always, there were several items, not on sale but on show, which became the subject of repeated interrogation and discussion.

One of these was a fabulous time printer from Löbner of Berlin, of exactly the type used at the Berlin Olympics, together with a Ulysse Nardin pocket chronometer, to record race times (see Schraven’s article on Short Time Measurement in Antiquarian Horology , Dec 2015).

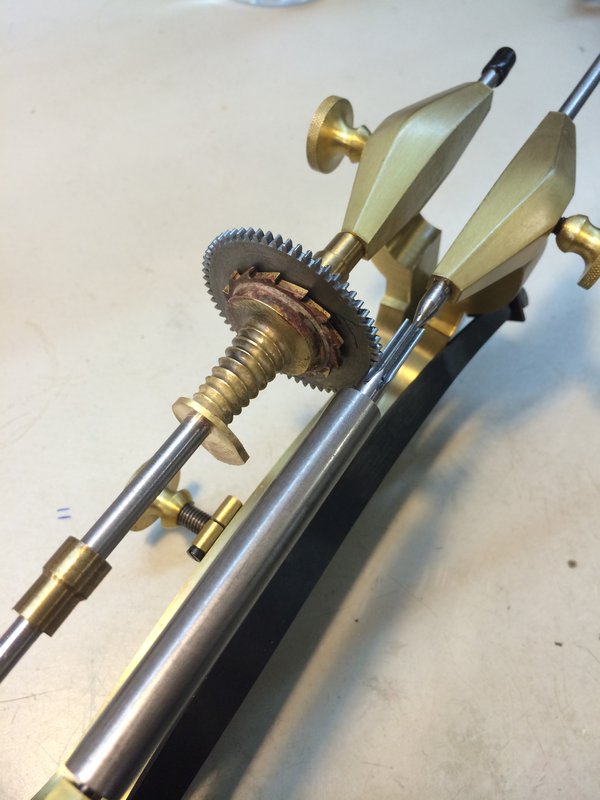

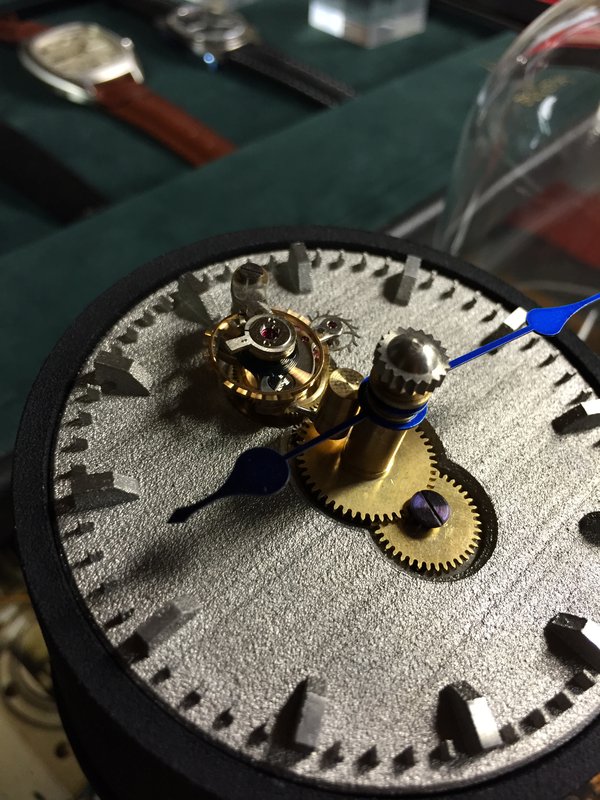

Another crowd-puller was a stunning but miniature ‘turret clock’ from Hörz of Ulm, the only example known, and referenced in a single catalogue (c.1905). This involves two weight-driven trains – one going and the other, in place of striking, to drive a polwender each minute (the device which sends alternate polarity pulses to subsidiary clocks).

This extraordinary survivor of an early 20th century master clock saw groups gathered for extended periods of time, counting teeth and attempting to rationalise the apparently problematic logic of its design.

A fabulous, multi-cultural weekend of fun, fine food and great friends.

Plans for an important clock

This post was written by James Nye

St Luke’s church (c.1825) in West Norwood, London, has an extremely fine clock (c.1827) by Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy, costing some 3 per cent of the budget for the church and the equivalent of several hundred thousands of modern pounds.

It is probably the first flat-bed turret clock in England, embodying ideas developed by Vulliamy on recent Continental travels.

Vulliamy’s clocks were substantially more expensive than those of his competitors, but he boldly claimed they would outperform and outlive cheaper alternatives. While it may not presently be working, a recent survey of St Luke’s revealed a very high quality clock, still in remarkable order.

Clock towers are deeply inhospitable environments, cycling in temperature between plus 40 degrees C and falling below zero – with humidity varying from low to 100 per cent over time.

The natural modern trend to move away from weekly attendance by a clock winder necessitates auto-winding, but St Luke’s system has failed.

There are further problems. Vulliamy’s slate dials were replaced with opal glazed versions in 1928, but the putty fixing of the panels has dried to a cement-like hardness, and the lack of flexibility allows for cracking of the glass, as the cast iron tracery expands and contracts.

Moisture can creep in, leading to ‘rust-jacking’. Several panels failed long ago, being replaced in wholly unsuitable plastic, offering a patchwork impression at night. Many other panels are cracked, and the eventual failure of the glazing is certain, while the clock room suffers.

The church is now launching a substantial project to repair the clock, add new auto-winding and auto-regulation, but, significantly and most expensively, also to repair all four dials with new opal glass.

This is a project of great significance to the community of West Norwood – the clock is highly visible and a symbol of local civic pride over two centuries.

Action and pressure from the local community has led to the present proposals for a project to restore the clock to function. Fortunately, a number of different members of the Society have also been offer to valuable input and assistance, and fundraising is well underway.

Fire! Fire!

This post was written by James Nye

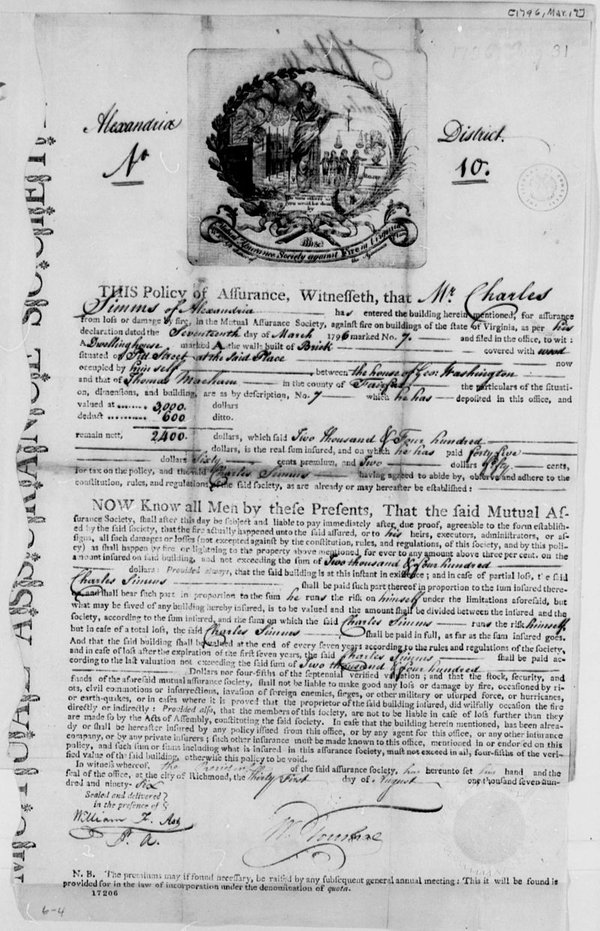

The AHS has launched a fascinating new research resource for its members – a series of searchable fire insurance records, covering the period 1710 to 1863.

Over many years, the late Roger Carrington (1948–2005) manually transcribed fire insurance records now held at the London Metropolitan Archive (LMA), and his work has been digitalized and added to the AHS web-site.

The LMA catalogue describes the holdings of a ‘substantial, if incomplete series of fire policy registers’ which survive for several insurance companies, including Sun Life (from 1710 to 1863), and Royal Exchange (from 1754 to 1759, and 1773 to 1863).

Roger focused on the policies of clockmakers and watchmakers, and related trades.

We have created downloadable and searchable pdfs. The key benefit is the digital searchability of all six thousand one hundred and twenty records involved.

What can one discover?

Well, as the catalogue notes indicate, ‘Where fire policy registers exist, they generally include the following information: policy number, name of agent/location of agency; name, status, occupation and address of policy holder; names, occupations and addresses of tenants (where relevant); location, type, nature of construction and value of property insured; premium; renewal date; and some indication of endorsements […] Sun Fire insurance policies were renewed after five years at which time a new policy was issued under a new number.’

The data are of great interest to the horological researcher for a wide variety of possible reasons.

The records can be searched for the name of a clockmaker, watchmaker or anyone involved in related trades. If the relevant name appears, the details of a policy can then be reviewed – potentially revealing new and interesting contextual material (e.g. verifying an address for a given date range, indicating prosperity or lack of it, etc.)

The records could be interrogated in a different way, for example by location, occupation or street name.

Many will find the searchable pdfs sufficient, in simply locating information to be found in the main policy transcriptions. However, some may wish to do more with the data, and to this end we have provided an index in Excel, which will allow for more sophisticated searches of the data.

This valuable resource is only available to AHS members, so do join up if you think it might be useful in your research. AHS membership is terrific value and your subscription helps support our mission to foster the study of the story of time.

The annual winding of the Mostyn Tompion

This post was written by James Nye

28 January 2016. To the British Museum, at the delightful invitation of the horology curators to take part in a little-known and wonderful ceremony – the just-once-a-year winding of the glorious Mostyn Tompion.

The Deputy Director, Jonathan Williams, offered a warm welcome, amply elaborated by Paul Buck, senior horological curator, who walked us around the origins and detail of this extraordinary object.

It runs for a whole year on one wind, striking every hour of that year (56,940 blows). The clock case, a confection of ebony veneer, silver and gilded brass, is rich in symbolism, covered in the heraldry and armorial paraphernalia of England and Scotland, richly intertwined – an interesting hint to the politicians who only wind each other up on such matters.

Made for King William III by perhaps our most celebrated maker – Thomas Tompion ( Westminster Abbey-buried, no less) – the clock descended on the royal death through various titled families before settling with the family of the early Lords Mostyn, finally landing in Great Russell Street in 1982.

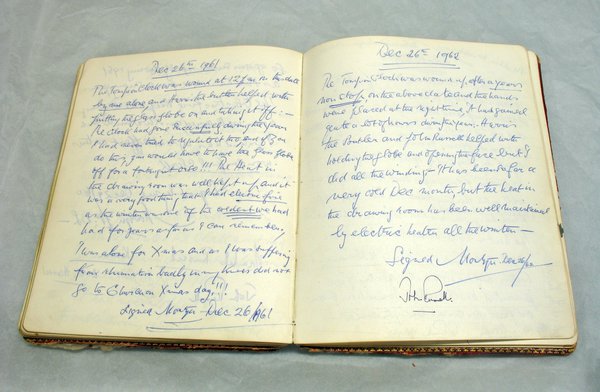

From c.1793, the Lords Mostyn held a small party to mark the annual winding of the clock, with each winder entering their name in a book. This tradition has been kept firmly alive at the British Museum.

The old family record was open for us to see, turned to the page for 26 December 1961, when Lord Mostyn recorded being on his own for Christmas, and winding the clock, which had ‘gone successfully during the year’.

Amusingly his idea of being on his own did not allow for the presence of the butler, who helped replace the dome over the clock.

These were memorable times – Mostyn, much troubled by rheumatism, also recorded ‘The heat in the drawing room was well kept up, and it was a very good thing that I had electric fire as the winter was of the coldest we had had for years’.

Winter, spring, summer and fall continue to unfold, watched over from Gallery 39 by a remarkable clock, which draws breath just once in each cycle of seasons.

Sushi, saké and a send-off

This post was written by James Nye

December 2014’s Antiquarian Horology featured a clock made in 1573 by De Troestenbergh in Brussels, rebadged and given as a gift (by Spanish survivors of a 1609 shipwreck off Japan) to the great Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

In May 2014, Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks worked on conserving the clock in a Japanese shrine, its home since the early 17th century, measuring and photographing everything.

The authorities wanted more than just conservation – they wanted a replica of the movement, sitting alongside, so that visitors could understand the magic of this striking and alarm clock, four centuries old and plaything of their most revered Shogun.

In August 2015, Johan and David Thompson (the project’s ambassadorial godfather) travelled to Japan to witness the significant honour accorded to the replica on its arrival and installation.

This was no ordinary project. Johan could only rely on details taken over a week.

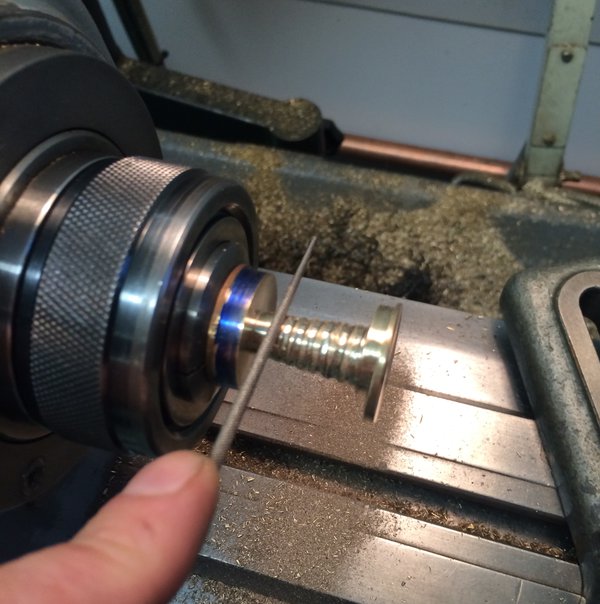

From mid-2014 to mid-2015, he devoted hours ultimately uncountable to producing a working copy of the movement. Pillars were turned with a hand graver, fusees roughly filed out by hand, flies cut and filed from the solid, shaped plates pierced out of steel plate, and so on.

Wheel teeth were formed using modern cutters, and modern machinery played a large role, but it was a year spent file-in-hand, forming, shaping and finishing.

Others contributed – notably the Whitechapel Bell Foundry for the bell, while the solid silver dial and hour hand were decorated by members of the Hand Engravers Association.

The original sits in a shrine, while Johan entered near monastic isolation for a year.

In August 2015, to mark his own long journey, to thank the many who had helped, and also to enlighten friends who had not seen him for months, The Clockworks hosted an evening of sushi, saké and Asahi. This was a chance to see the working replica before its long journey to Shizuoka, joining De Troestenbergh’s original.

It was a great evening, celebrating the traditional internationalism of horology in which a Dutchman in London worked to an ancient Flemish design to produce a clock for a Japanese shrine.

Campai!

Inspired reforms – magnificent outcomes

This post was written by James Nye

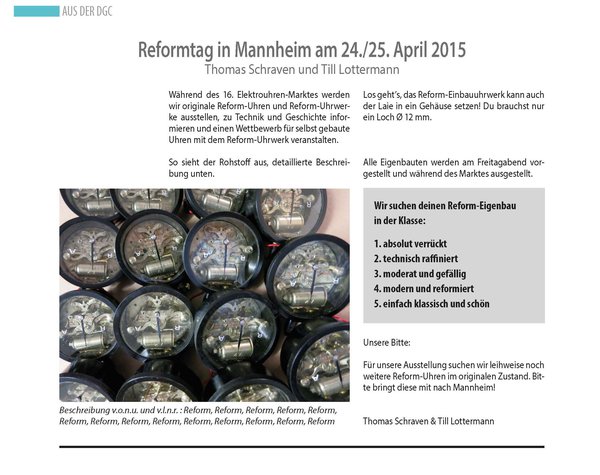

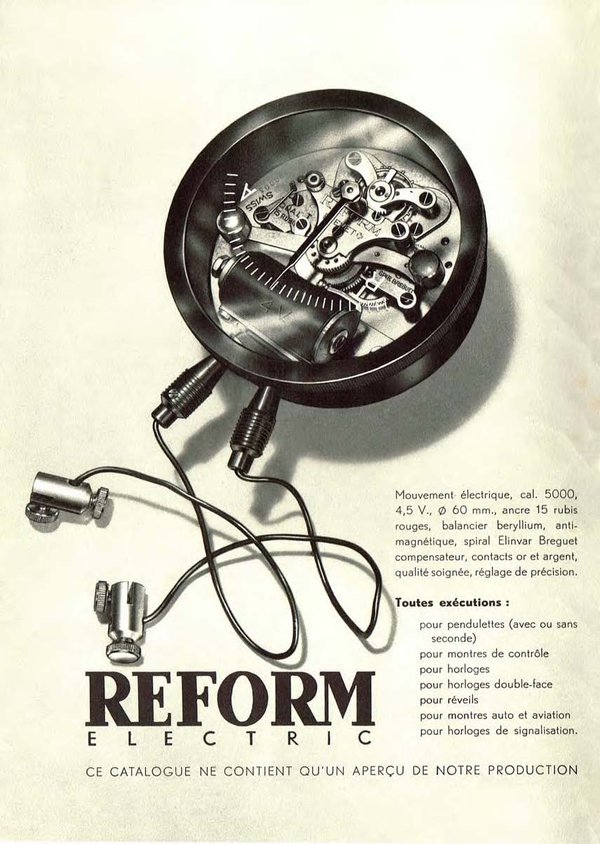

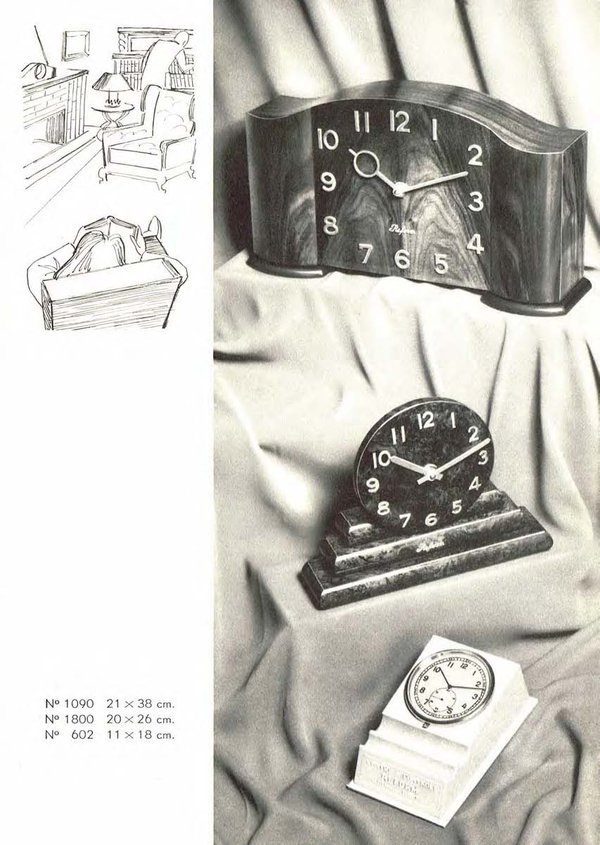

In May 2014, I blogged about a competition to devise uses for new-old stock 1950s Calibre 5000 Reform movements that had turned up at the annual Mannheim electro-fair.

I judged the entries on 24 May this year, and what an amazing event to witness. Here was a beautifully executed movement, simple, reliable, long-lived, but criminal to hide.

How to incorporate it in a modern design, and achieve a functional clock, when the attractive side of the movement would necessarily normally face the rear? In significant style, it turns out……

Ivo Creutzfeldt ignored convention and went for pure schlock with his tongue-in-cheek ‘winged chariot entry’.

Thomas Schraven offered a couple of entries, one channelling a strong modernist theme – using two movements, one for display, the other for timekeeping.

Eddy Odell showed considerable lateral thought, introducing the movement into a glass mug, keeping the movement visible to the top, while driving digital minute and hour bands in the base, the battery neatly hidden.

Till Lotterman and his home team colleagues offered a remarkable test exercise. Using original parts, they recut elements to form a tourbillon, brought out on the dial side of the movement, achieving real spectacle ( film here).

Not only this, they 3D printed a stylish stainless steel dial, and also 3D printed an open-sided plastic tubular case, with internal mirror to reflect the movement. Later we were treated to a lecture on the extraordinary possibilities emerging for 3D printing.

Finally, the most talked about item in the competition, Frank Dunkel’s inspired diorama clock, using the Reform at the centre of a roundabout, driving hidden arms carrying neodymium magnets, in turn propelling a VW Beetle (minutes) and VW van (hours) against perimeter hour markers ( film here ).

Power even arrives by wire supported on telegraph poles. Absolutely inspired!

The whole party retired to a restaurant for the evening, at which, amidst characteristically heroic levels of consumption, we celebrated the amazing results of our competition – prizes all round.

New lease of life for a distinguished old gent

This post was written by James Nye

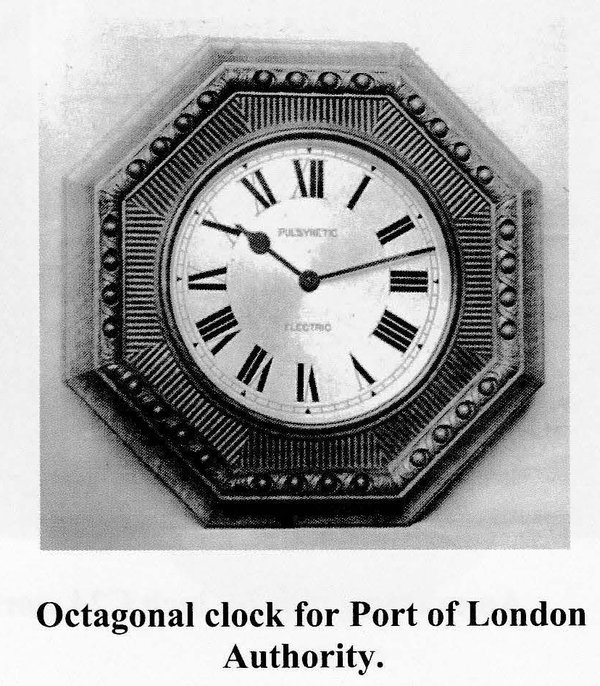

Featured in James Bond’s Skyfall in 2012, the former Port of London Authority building near London’s Tower Hill is undergoing significant change, to become luxury apartments and a hotel, badged 10 Trinity Square.

The building was opened in 1922 by Lloyd George, and its boardroom hosted a reception on 30 January 1946 in honour of the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, which had commenced earlier in the month ( The Times , 31 January 1946, p. 7).

The boardroom was recently the focus for dramatic renovation works, with original surfaces being repaired and refinished.

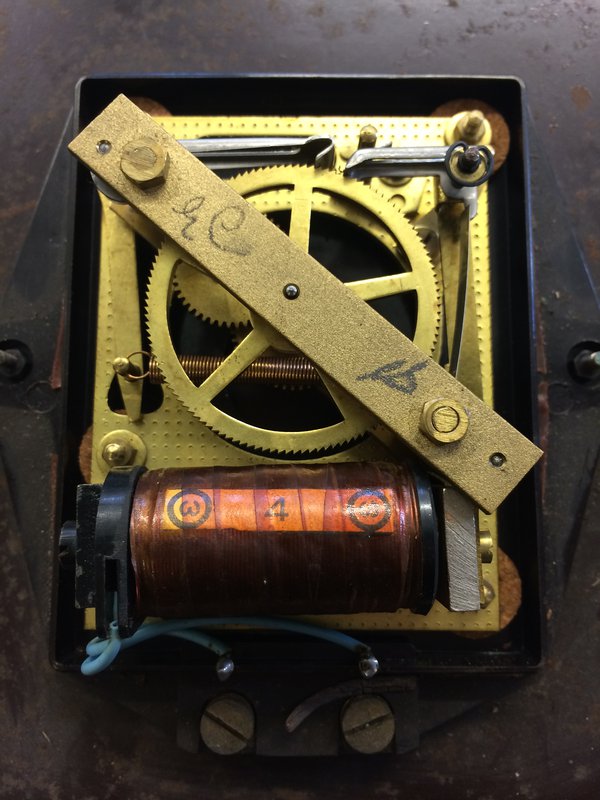

One relic from an earlier incarnation of the building to which the new owners turned their attention was the Gent Fig. C423 insertion feature clock, mounted in a panel above the balcony doorway.

This model was designed for the Festival of Britain in 1951. It is therefore clearly a later replacement of the movement first installed in 1922, but Colin Reynold’s excellent Conspectus of Clocks and Time Related Products Produced by Gent & Co Leicester (Leicester, 2011) illustrates the original pattern.

The current orphaned dial has lost the rest of its network of C7 master clock, and perhaps a hundred dials that might once have populated the building’s many rooms.

Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks was asked to attend to see what could be done to make it work.

Apart from the required servicing of the movement, the obvious solution was to provide a small self-contained master clock mechanism, quartz-controlled and battery-driven, to be hidden inside the panelling.

This parsimonious and relatively inexpensive solution has ensured the retention of a historic clock, in its original setting, and without the replacement of any parts. The old Gent lives to fight another day.

War time reflections

This post was written by James Nye

The June centenary of the Archduke’s assassination is behind us, though in July 1914 no one imagined a world war breaking out a month ahead (head to the LMA for a great new exhibition).

In May, my talk at Greenwich—‘Bang on Time’—focused on 1940s clockwork devices used for delaying explosions, and it seems quite a few of my blogs dwell on bombs and destruction. Today, I reflect on some horological titbits from the Great War.

For a start, patriotism (and then conscription) emptied out light engineering and clockmaking firms of their young workers.

Of the 450 staff at Smith & Sons (MA) Ltd, floated in July 1914, nearly 10 per cent were at the Front a month later.

Silent Electric’s Herbert Bowell confirmed to the authorities in March 1917 that all his employees had signed up in 1914.

His better-known brother George, by contrast, was a munitions worker—the path for many other craftsmen.

After the ‘Shell Crisis’ of May 1915, resources poured into shell and fuze-making capacity, with the result that millions were crafted, to be fired on the battlefields of Europe. Though military demand for chronometers and timekeepers of all sorts mounted rapidly, clock and watchmakers from Clerkenwell were packed off to the north-east to work in firms such as Vickers, to manufacture fuzes.

While the factory workers and the soldiers they supplied are long gone, their products endure.

A standard artillery fuze might delay firing the main charge by up to half a minute. Precise (and expensive) fuzes had a clockwork escapement (see video) while vast numbers were simply igniferous, though even then involving a dozen or more precisely machined parts.

These remarkable engineered brass mementos regularly emerge from the soil a century later, and will still strip down.

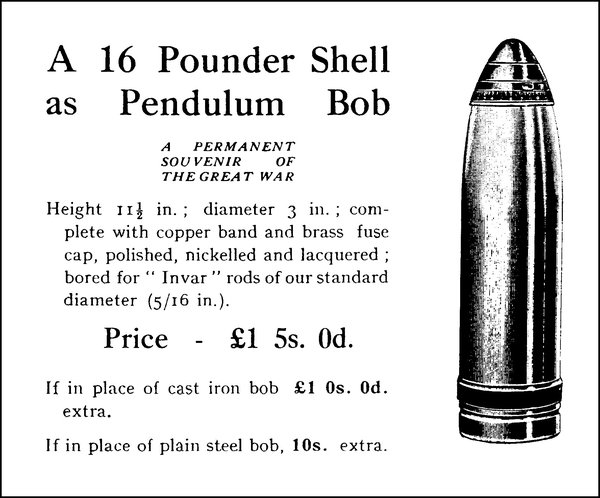

While surplus shell cases formed myriad household ephemera for years – Trench Art – another astonishing survivor was courtesy of the clock trade itself, in an idea from the irrepressible Frank Hope-Jones, who purchased 16-pounder shells (and fuzes), offering these as a pendulum bobs—a ‘souvenir’ of the Great War. What a blast!

There’s never been a better time for reform!

This post was written by James Nye

A gauntlet has been laid down. Across Europe, thoughtful people are busy working up ingenious ideas for a competition devised over an extraordinary April weekend in southern Germany.

Each year, several dozen of the electro-horo-cognoscenti gather in Mannheim-Seckenheim for an event organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven.

The fifteenth of these gatherings—a combination of market, lectures and much eating, drinking and good conversation—saw a new visitor who brought many interesting items, not least several hundred new-old-stock Reform movements, tissue-wrapped and boxed.

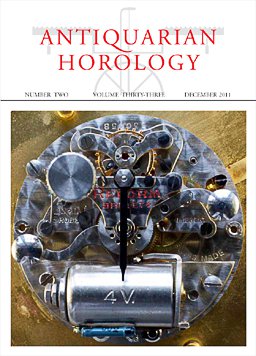

Alert readers will recall an Antiquarian Horology cover featuring a classic example of the Reform calibre 5000 movement, and a fascinating accompanying article.

As David Read comments, these Schild movements are ‘without doubt the best known and most commercially successful of all the many varieties of electrically-rewound clock movements’ from the 1920s onwards. The calibre 5000 is a lovely object, jewelled, with damascened plates, and micrometer regulation.

Nye’s theorem proposes that hi=as*bc/ebw where hi stands for horological inventiveness, as represents afternoon hours of sunshine, bc denotes beers consumed and ebw stands for evening bottles of wine.

With a lively group, talk over two sunny days and late evenings turned to possible creative uses for virgin Reform movements.

Given their looks, the mechanism must remain visible, but the motion work is to the (unremarkable) reverse. This led to discussions of projection clocks, or elaborate gearing to present time in the same plane as the movement, but to one side.

There was even intriguing talk of a large scale tourbillon. More detail than this presently remains closely held, but a competition to determine the best use was announced, to be decided in Mannheim in April 2015.

Reform is the order of the day.

Clock world full of cranks?

This post was written by James Nye

Things turn up. Back in 2006, when David Rooney and I were researching the Standard Time Company (STC), we planned a lecture at the Guildhall library.

The only surviving early clock we knew of had spent its life at the Royal Observatory—but out of the blue, days before the event, a Lund-synchronised dial clock turned up.

In the following eight years, that was it—nothing else—and then suddenly, through the kind agency of Keith Scobie-Youngs, The Clockworks acquired a wonderful addition a few weeks ago, in the form of an outsized fusée gallery movement, fitted with a massive Lund synchroniser.

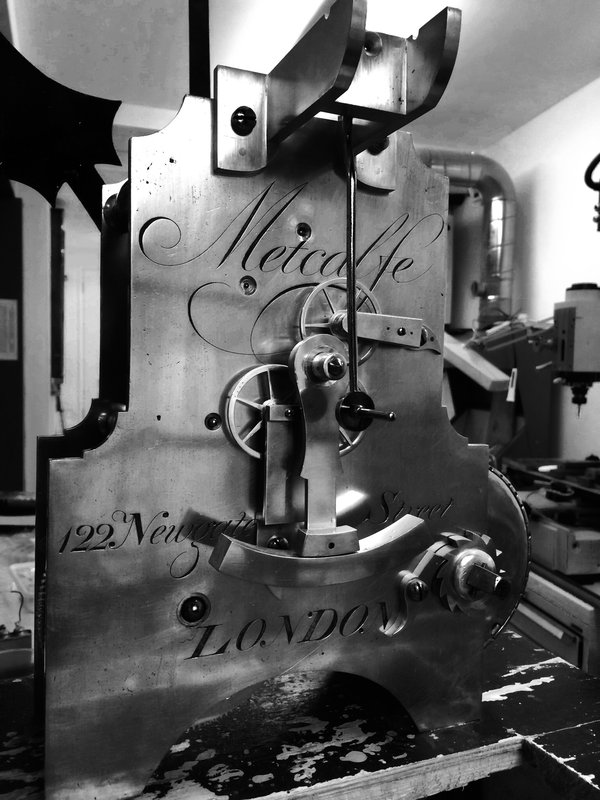

The movement is by Thwaites, from the early nineteenth century, and signed elaborately by Metcalfe of 122 Newgate Street, London.

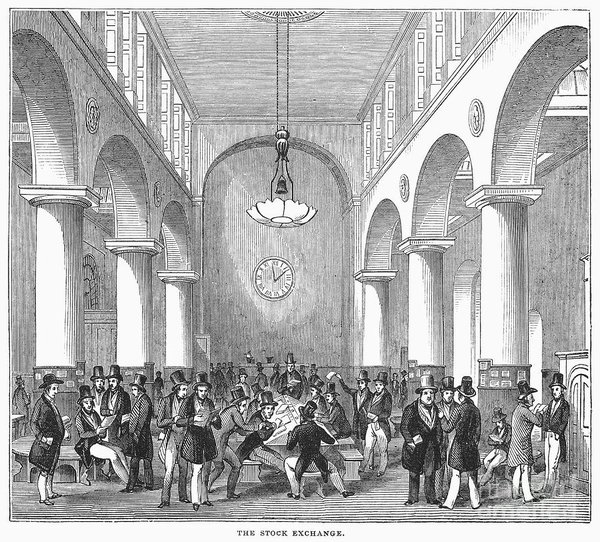

When STC went public in 1886, it listed its clients in the prospectus, and the very institution on which it was being floated appeared second in the list.

The accurate timing of bargains made by the jobbers on the London Stock Exchange was an important matter, and ‘the House’ was an early adopter of the new technology that provided hourly synchronisation of its clocks.

Remarkably, our new addition was one of probably several STC-synchronised clocks that populated ’Change, where it seems to have served for some time.

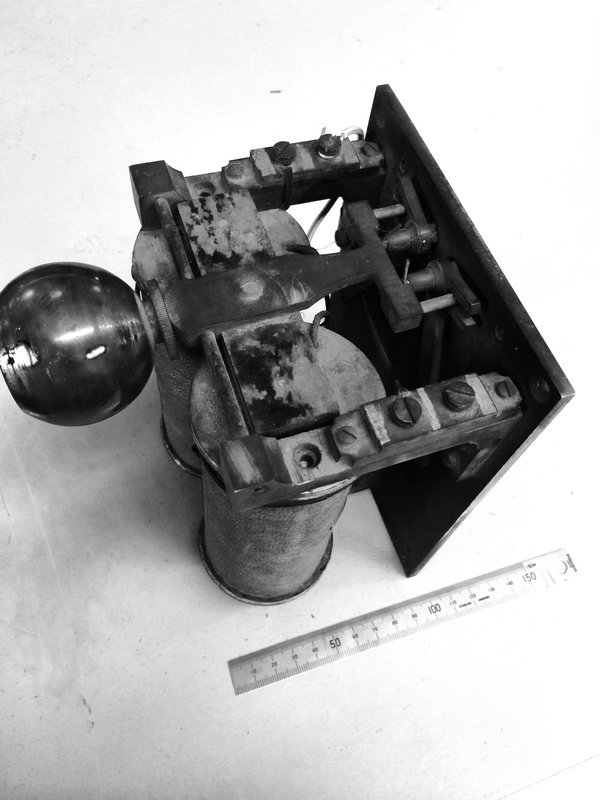

Each hour, a signal would travel from STC’s offices on Queen Victoria Street around a series of looped networks, energising the coils of the synchronisers. These were the ‘set-top boxes’ of their day, added perhaps many decades after a clock was first made—as was clearly the case with this clock.

The Stock Exchange synchroniser is particularly large, operating two small fingers that project through the dial, to correct the minute hand each hour. The long use of the device is evidenced by the deeply indented witness marks in the tab on the back of the hand, caught by the synchroniser.

.

Overall the movement seems rather outsized for the scale of the dial it ended up supporting—the large counterweight is much more than a match for the 15-inch minute hand.

Sometimes, it’s very hard for us to trace the environs in which our clocks spent their time—and to deduce whose lives they counted out. Thankfully in the case of this remarkable STC clock, there’s an old crank that can tell us a story or two.

Graveyards, clocks and bombs

This post was written by James Nye

Things end up in graveyards at the end of their lives, but monuments to the passing of much else can be found in other locations.

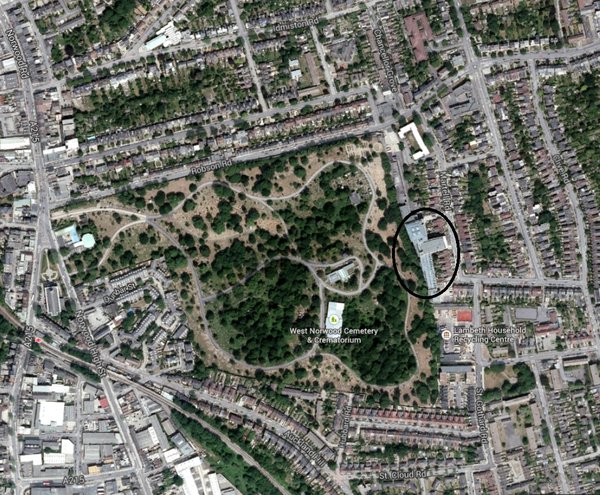

I live in West Norwood, home to one of the ‘magnificent seven’ London cemeteries.

On its eastern boundary lies the Park Hall Business Centre. This thriving modern enterprise occupies the former Hollingsworth Works of the Telephone Manufacturing Company (TMC).

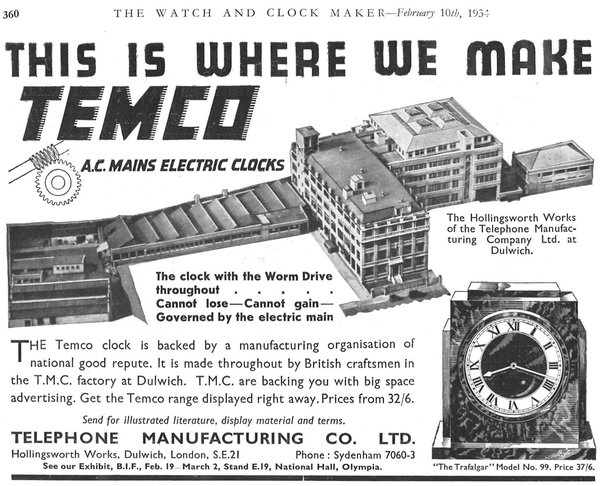

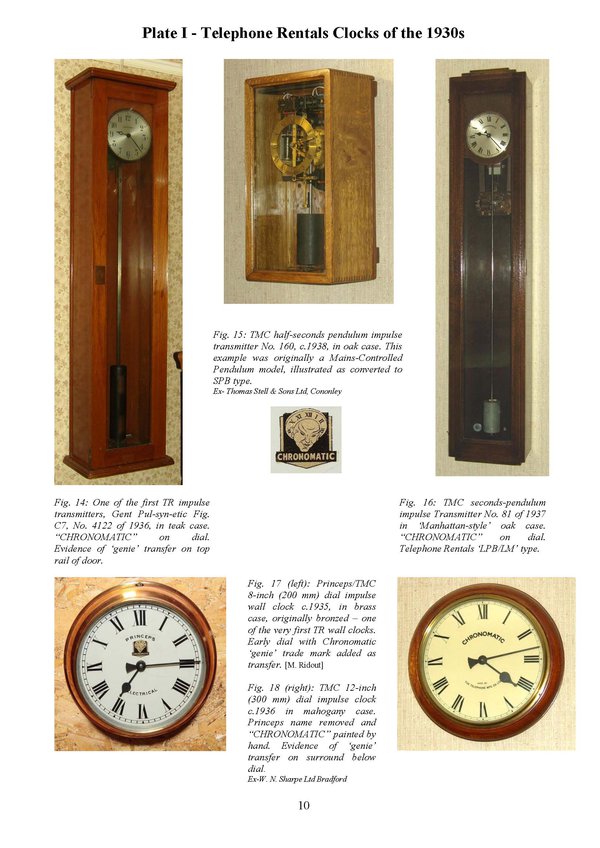

This firm did just what its name suggests, but was also a prolific maker of industrial timekeeping systems, rented out under the name Telephone Rentals. TMC’s ‘TEMCO’ synchronous clocks are featured in the latest NAWCC bulletin.

TMC occupied the Dulwich site from the early 1920s, employing a large local workforce—1,600 by 1937. Workers from the other side of Norwood Road used to talk of ‘walking the wall’ to work, following the long cemetery flank wall, down Robson Road.

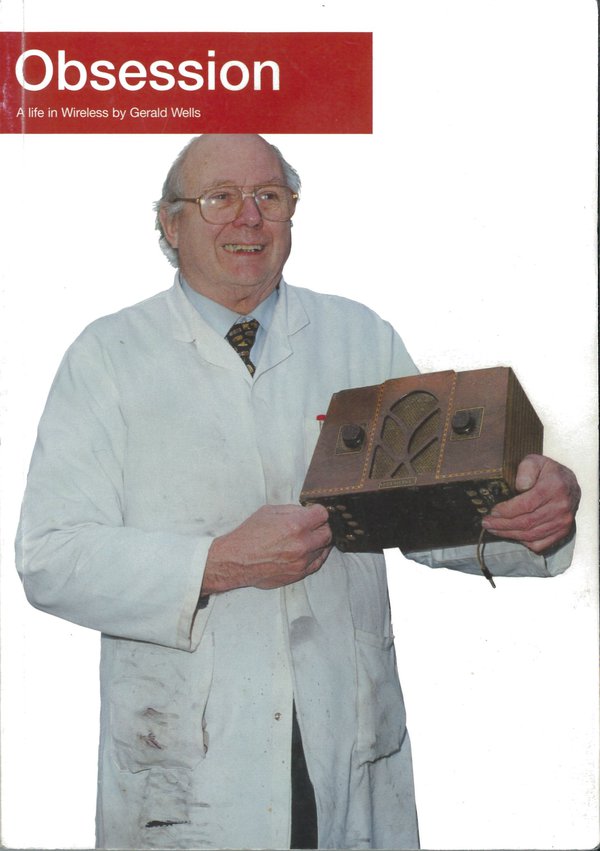

Involved in contemporary ‘hi-tech’, the factory was a natural wartime target—Gerald Wells’ extraordinary autobiography describes twenty-seven bombs falling on the cemetery, targeting TMC, but then the Luftwaffe became:

‘fed up with wasting bombs on Norwood Cemetery so they decided to get the TMC factory by lowering a large naval magnetic mine on a parachute over the building. My sister Margaret watched it come down from an upstairs window […] it knocked seven colours of s*** out of our little Congregational Church’ ( click for a bombsight map —work in progress).

So Hollingsworth Works survived, and TMC/TR had a more successful post-war life than many clock-related concerns.

You can learn much more about the company’s life and products from a superb paper by Derek Bird—these technical papers are a feature of EHG membership. Why not e-mail me to get on board? And put 7 September 2014 in your diaries—part of Lambeth History Month—when The Clockworks will offer a special locally-themed event, featuring TMC.

Happiest days of your life?

This post was written by James Nye

Recently we hosted the BHI North London branch at The Clockworks. It was a great visit, filled with observations and anecdotes about life among clocks.

Always popular, we looked at the Gent’s 'waiting train’, or ‘motor pendulum’. A neat design, synchronised to an accurate source, it has the power to overcome harsh winds or snow impeding the hands, compensating with more frequent impulses when needed.

Chatting over a coffee, stories emerged of people’s introduction to clocks and watches – particularly electric ones.

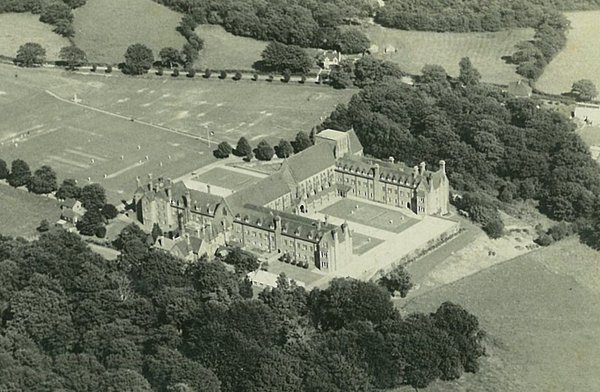

I described how, at the age of 13, I was put in charge of my school’s Gents-based clock system (for the nerds, C7, C69, C150 etc), including a waiting train in a tower above. One guest mentioned that coincidentally it was the same for him – being asked to tend to just such a school system.

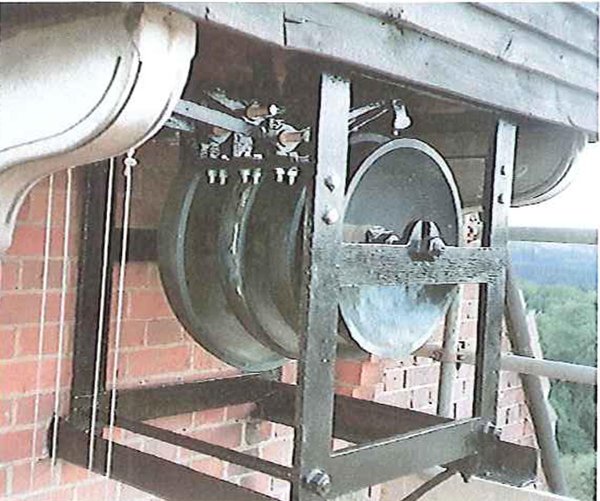

This prompted me to describe a feature of the system I maintained. A flatbed turret clock (David Glasgow, 1911) provided a chime and strike on bells, tripped by a solenoid, in turn controlled from the waiting train, using four aluminium sails (like a windmill) mounted on the bevel nest, operating each quarter on a microswitch – an ingenious addition.

‘Which school was this?’ asked a misty-eyed guest. ‘Ardingly College’, I replied. ‘That was me,’ he said softly, ‘probably in 1950.’

A quarter century apart, we had both been responsible for the same system. George D’Oyly Snow, headmaster, was fed up with chimes sounding at the wrong time, and with limited funds, but knowing the inventive skills of his boys, he commissioned my guest to find a solution – a solution still functioning into the late 1970s.

A theme I mentioned in a recent lecture is the serious risk to which electric clock systems are subject when their caretakers or installers move on.

The Ardingly Gent system, probably in service since the 1930s, was replaced after approximately 60 years by a radio-controlled master clock, and Thwaites & Reed recently reworked the flatbed movement, installing motor-wind, and even synchronization.

George Snow can rest easy in his grave – the chimes still sound on time. But to my mind they must sound a plaintive note as well – curiously, I feel desperately cheated of part of my heritage, and I know someone else who probably feels the same way.

Can we sex-up the time-recorder?

This post was written by James Nye

We’re used to seeing Hollywood actresses, the latest haute horlogerie on their wrists, gazing at us in dreamy soft focus. But what about the advertisers looking to push horlogerie industrielle?

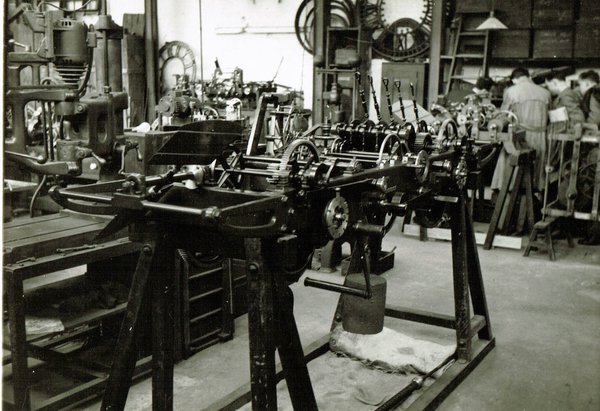

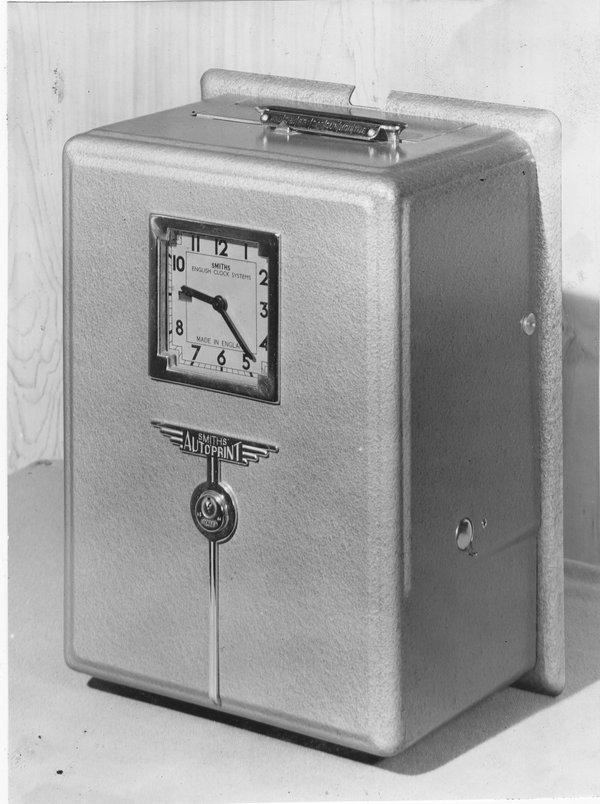

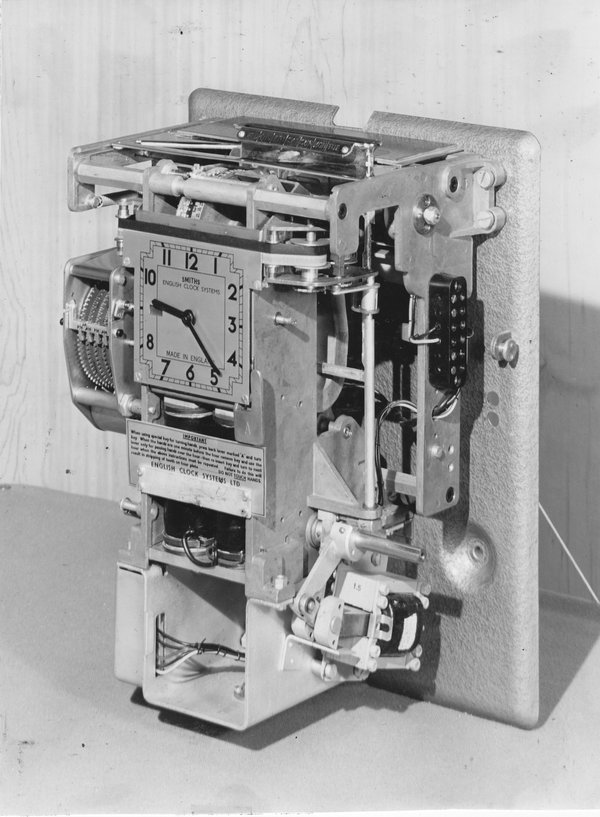

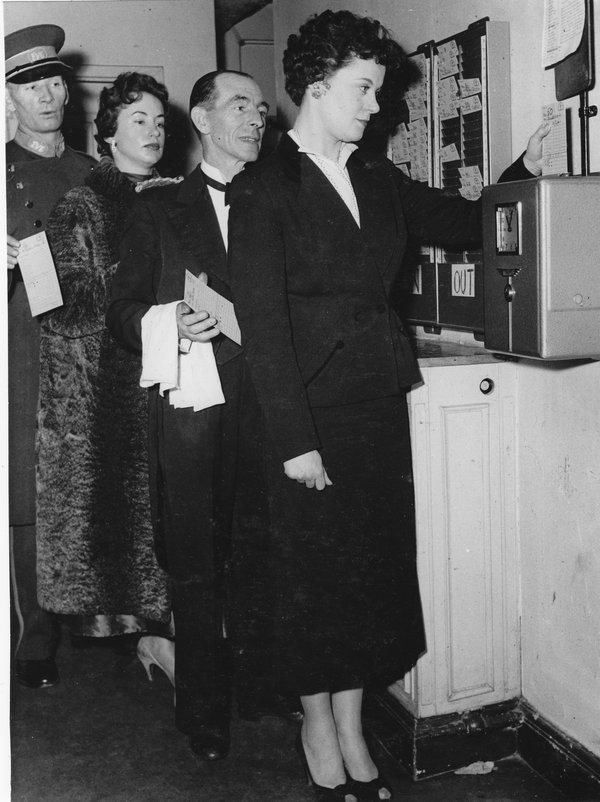

In an earlier blog I presented some pictures from inside the English Clock Systems (ECS) works at King’s Cross from the early 1950s. One of the shots showed the production line for the time recorders. The final product – the Autoprint – was a superb machine, and here are a couple of shots, showing both the mechanism and the outer casing.

The problem facing the ECS publicity unit was how to make the machine a bit more interesting in a catalogue or journal report. Watches and exotic locations were one thing, but the time recorder presented a bit of a challenge on the face of it. In this blog I speculate on the thought process of the lads as they set to their task.

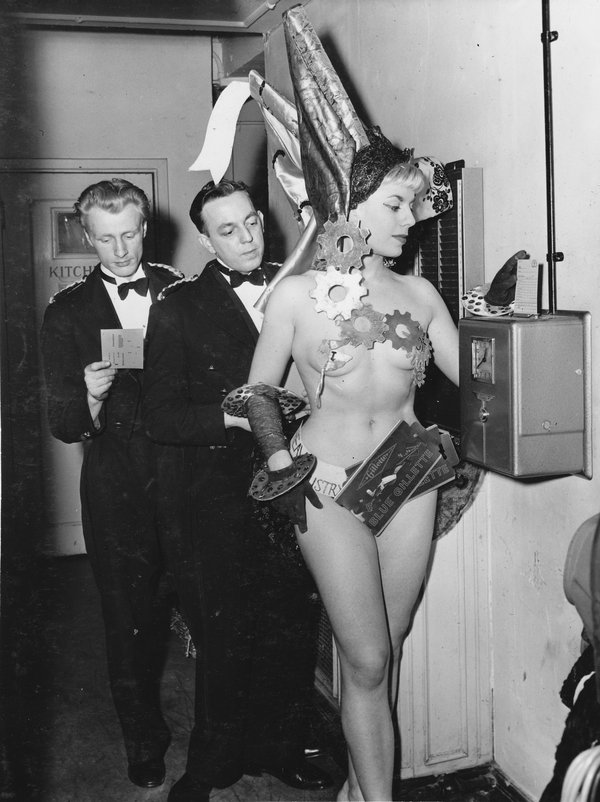

The Autoprint was proudly on show at the 1956 British Industries Fair. The display stand was duly photographed, but an attraction for businessmen that year was a trip to the Eve nightclub on Regent Street. Our intrepid team tagged along, and lo and behold, the nightclub staff used an Autoprint!

A first shot caught the commissionaire and other colleagues stamping their cards, but patience was rewarded with the arrival of a hostess, happy to pose.

Finally, of course, the show-girls themselves arrived – all adorned with representations of items manufactured in Britain. The third image shows Gillette-girl!

Picture Post (7 January 1956) carried a double-page spread on the cabaret, illustrating different industries from the BIF, but the historic industrial horological shot shown here remained hidden in an archive until I stumbled across it recently. In the interests of scholarship I felt it should be published.

When is a wrist watch not a watch?

This post was written by David Read

In February 2013 it was leaked that Apple was experimenting with an iWatch. However, six months later and at the time of writing this blog there is still no news from Apple and the technical press is now guessing that the project has hit battery problems.

If only Dick Tracy, the famous cartoon sleuth, was still around to find out what the bad guys are up to and get at the iWatch facts. Tracy had sported a remarkable watch on his wrist since 1946 and now, 67 years later, Time Magazine described that watch as 'the most indestructible meme in tech journalism'.

For decades now, it has been nearly impossible to write about communications technology combined with a wristwatch without invoking the plainclothes cop with a special watch on his wrist who first appeared in 1931, even though the days when one could follow Dick Tracy’s adventures in a daily newspaper have long gone.

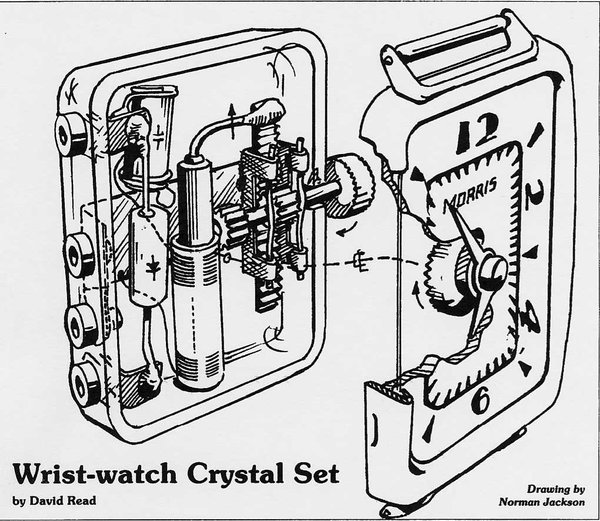

Popular science fiction is always years ahead of the technologies that turn dreams into reality. However developments in solid state electronics had, by the 1940s, enabled the large galena and cat’s whisker detector of the crystal set to be produced as a tiny point-contact diode and placed inside a wrist watch case as in the Morris watch shown here.

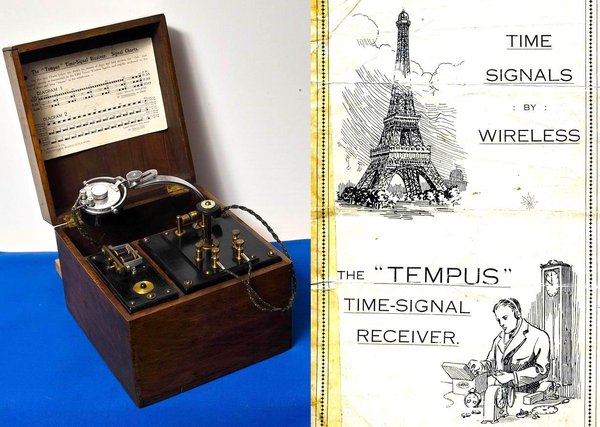

But is this a watch? No, it’s a crystal radio. However, horology and radio have a long shared history involving frequency and time. This clandestine wristwatch radio can receive time signals in exactly the same way as mariners and watchmakers did from 1912 in order to check their chronometers, clocks and watches against the timecode transmitted from the Eiffel Tower. My image of the Tempus crystal radio and instructions sets the scene.

The illustration of the Morris watch shows a standard-sized watch case made of chrome-plated steel. The dial, signed Morris, is in typical 1940s style. The standard of manufacture is high and the disguise on the wrist is perfect. The case back is made of moulded Perspex to provide an insulated chassis on which the circuit can be built without special measures to insulate the components, aerial, earphone sockets and associated wiring.

The winding button is actually a dial knob and connects to a rack-and-pinion control of tuning in which an iron-dust core is moved within the aerial coil and tunes the required frequency by altering the coil’s inductance. This assembly is connected to the earthy end of the coil and also to the metal case thus providing a body earth to stabilize the circuit whilst tuning. A tiny sealed point-contact crystal detector is enclosed in an evacuated glass tube and a capacitor across the coil completes the circuit.

A second pinion on the winding stem connects with a crown wheel on which the hands are mounted. This alters the position of the hands on the face of the watch and provides a scale against which a station can be memorized or noted. Using the wrist watch crystal set in conjunction with a deaf aid as an amplifier would have allowed the use of a short aerial such a bedstead and completed the disguised operation.

The drawing was made for me in the 1980s by my late dear friend Norman Jackson, an outstanding engineer and artist whose illustrations always showed at a glance how things work; something that photographs can never match.

It is interesting to speculate why such a radio was made and I have never seen another. However, the Morris watch cannot be unique because it is a professionally designed object requiring bespoke production tooling and Perspex moulding facilities. The public market for such clandestine receivers would have been tiny and with no chance of recovering the costs involved. Without a consumer market for this item it would seem possible that it was funded by a government agency and the headline news today shows that such agencies are still active in the ancient arts of listening, spying, and gathering information.

And another thing – yes it does work!

It’s for the birds

This post was written by James Nye

Some pigeon racers were cheats. This was the shocking brief given to the Skymaster Clock team in the 1950s when refining their latest patent racing clock.

It was a serious business for the 100,000 registered pigeon fanciers in Britain, and rigid standards were enforced. Defeating the few cheats involved some inspired horology, and when I heard how clever the solution was, I wanted to share it here. But first, let’s understand the basics.

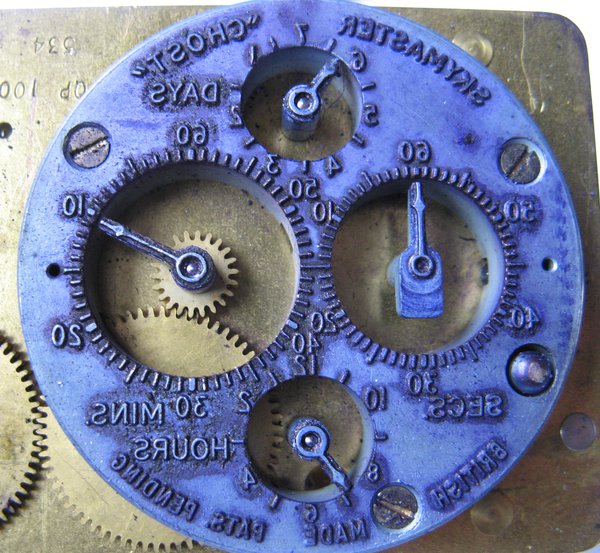

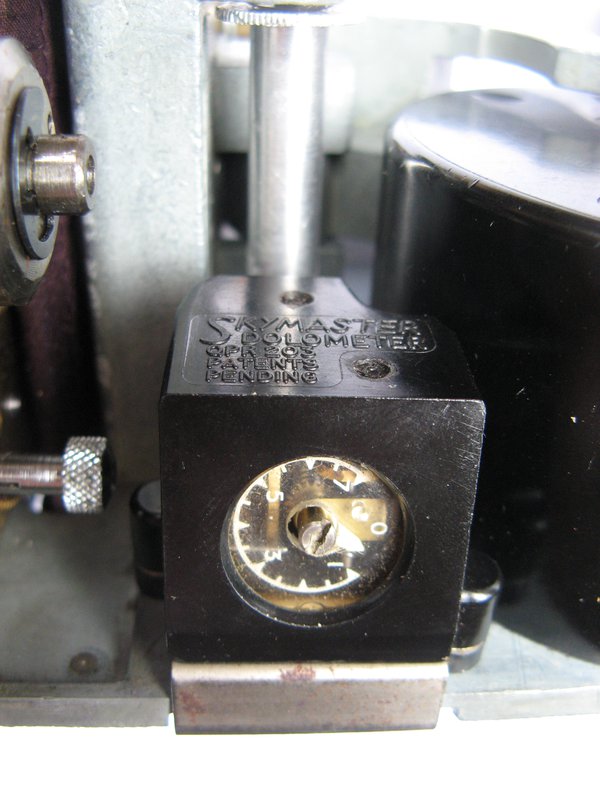

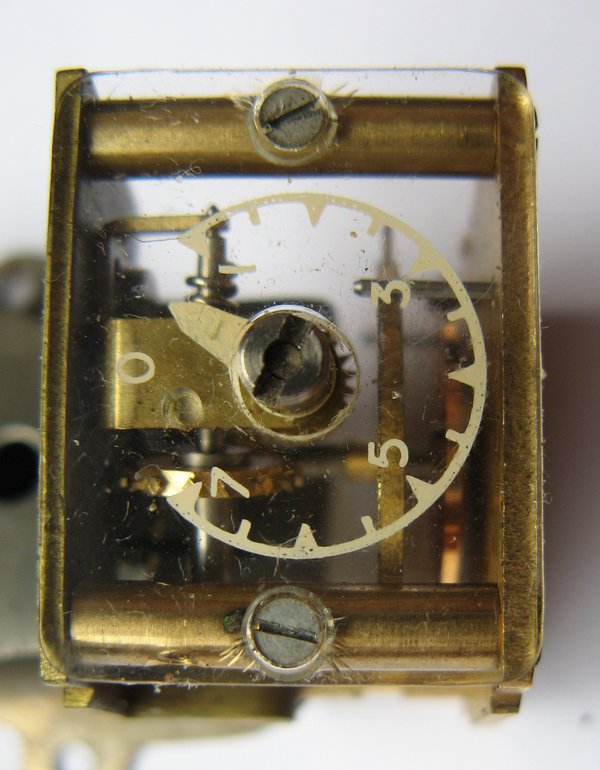

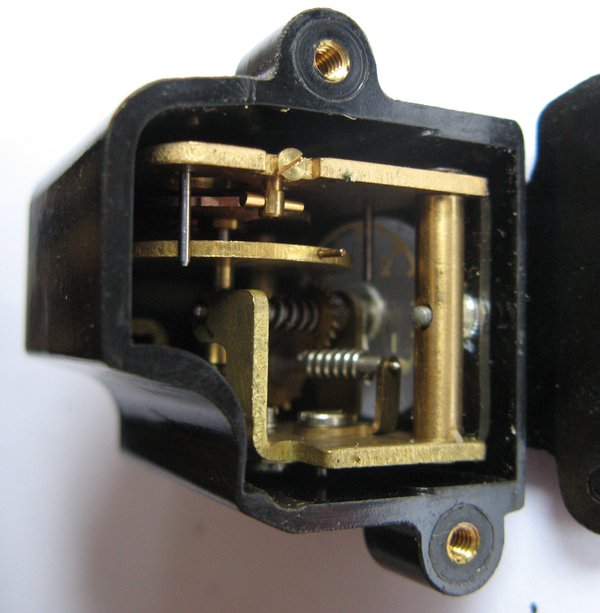

The Skymaster clock contains a 7-jewelled platform escapement movement, coupled to an inked ribbon stamping mechanism (like a time-recorder) which presses a paper tape against an internal mirror image dial (in relief), recording the time a returning pigeon’s identifying ring is inserted.

Races are won by seconds. Pigeon clocks are meticulously checked and every option to cheat is blocked. But unscrupulous fanciers had come to believe that platform escapement clocks could have their rates meaningfully altered, for example by swinging the clock in the same plane as the balance, so that they might both retard the locked clock (ideal before the pigeon arrives) and advance it (needed once the pigeon is back) to get it back to time before being examined by an official.

The effectiveness of these methods is uncertain but, nevertheless, Eric Moss and Bruce Alexander of Smiths were compelled to devise a brilliant solution for the Skymaster – called the ‘Dolometer’. They based it on an electro-mechanical car clock, in which typically an inverted-Sully escapement (electrically driven) advances the train. See an animation here. They removed the magnetic drive, and relied on the overall motion of the clock to drive the Dolometer – thus the dial reveals the degree of any shaking.

Calibrate for ‘normal’ activity (the natural joggling of a journey home to the loft, plus a margin for error) and if the Dolometer shows an excess, you have detected a naughty pigeon fancier’s attempted fraud. Bruce Alexander carried a dolometer for days – even cycled with it – to work out what a normal reading would be.

This seems to me to have been inspired thinking on the part of the designers. And it inspired me to acquire a Skymaster so that I could dismantle and photograph it for you.