The AHS Blog

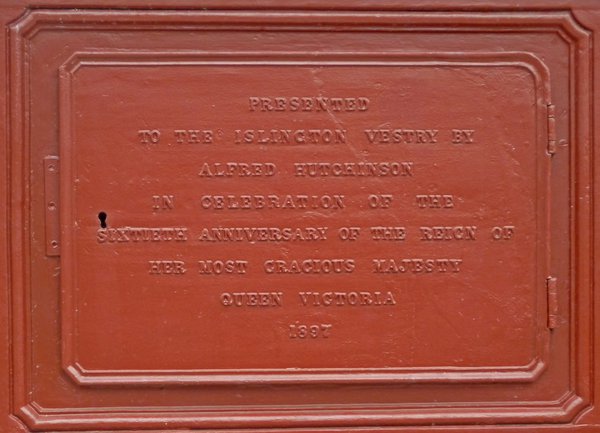

Clocks and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Cycling through north London I like to pass by the Jubilee Clocktower at Highbury, Islington, near the Arsenal football stadium. It was erected in 1897, sixty years after Queen Victoria came on the throne. And in the March 2011 issue of Antiquarian Horology we published a photo of a jubilee clocktower at East Harptree, Somerset, taken during one of the regional excursions of the AHS Turret Clock Group.

These are just two of what must have been dozens, perhaps hundreds, such clocktowers that bear witness to the commemorative zeal of the late Victorians. In February 1897, a specialist firm issued the following circular letter intended to generate new orders:

'We desire to draw the attention of the Nobility, Clergy, Gentry and others, who are contemplating the erection of Church and Turret Clocks in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, to our unrivalled facilities for manufacturing all kinds of clocks at the lowest possible prizes consistent with good workmanship and material, and to all requiring the same we would be glad to furnish estimates and information free of charge.'

Quoted from Michael S. Potts, Potts of Leeds. Five Generations of Clockmakers (Mayfield Book 2006), p. 133.

Many orders came in. The smallest clock tower that Potts installed in 1897 stands, fourteen feet high, on the town square of Much Wenlock, Shropshire.

Wikipedia has a list of jubilee clocktowers which also includes examples erected ten years earlier for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, like the one on the seafront at Weymouth, Dorset. They were also built in outlying parts of the British Empire. The Victoria Clocktower in Georgetown, Malaysia is still a well-loved landmark. It is sixty feet tall, one foot for each year of Victoria’s reign.

It would be great to have a proper study of these late nineteenth-century jubilee clocks and clocktowers, with a gazetteer telling us where they are, and of course who supplied the clocks. Something for a website, a book, or perhaps an article in Antiquarian Horology?

Walking the ‘Willett Way’

This post was written by David Rooney

Every spring, when we put our clocks and watches forward for British Summer Time, we do so with a hollow laugh. March weather is rarely summery! But last month many in the UK have seen prolonged sunshine, and in London we’ve had a heat wave. Summer arrived at last.

If you like walking in sunny weather, and if you’re in London, you can combine a walk with finding out more about British Summer Time. It takes in Petts Wood and Chislehurst, home of William Willett, the schemes creator, and it’s easily accessible by public transport.

You can view the walk instructions online or print them off. But I must warn you that it’s a while since I prepared this trail, and things might have changed. Do take care and, if in doubt, follow your common sense, not my instructions! One thing that changed since I wrote the walk is the refurbishment of Willett’s grave, now looking superb.

It fascinates me that twice a year, every year, quarter of the population of the Earth changes its clocks and watches for summer time. That is a real, physical, close engagement between billions of people and billions of timekeepers each year across the globe—all because a Victorian British house-builder and moralist thought we should get up earlier in summer.

What this shows is the sheer power of clocks and watches to change and order human behaviour—or rather, the inventive ability of people to use time to control other people. We can see it all over the place when we know what to look for. Time is a political tool.

And that is one reason why you should join the AHS. Knowledge is power, and the more we understand timekeeping, the more we can understand the control that people exert on our lives using it. PS I’ve recently joined Twitter. If you’ve nothing better to do, you can follow me @rooneyvision.

Just so you know how rich I am

This post was written by David Thompson

Today some people wear expensive watches partly to demonstrate their wealth. They either sparkle with diamonds or they impress with their complexity of mechanical magnificence. You might think that this is a new idea, but in fact this tradition goes back centuries to when the first watches were made in the early part of the 16th century.

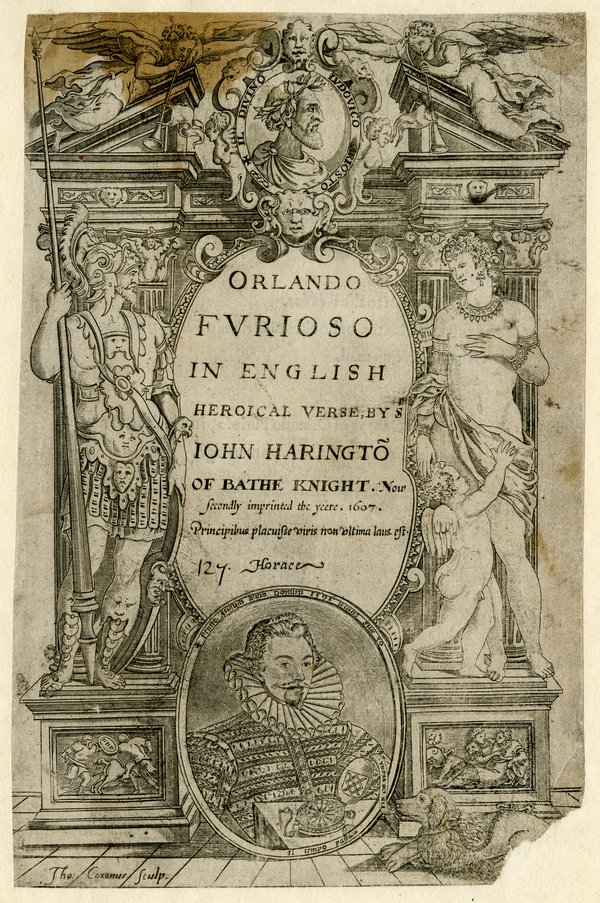

An interesting example of this comes from the title page of Sir John Harrington’s translation of Orlando Furioso, (The Frenzy of Orlando, an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto first published in 1516.) Harrington’s translation, which appeared in 1591 was the first in English. The story contains politics, war, religion and unrequited love as well as fantasy and consists of forty-six eight-line verses in rhyme – quite a challenge for the translator.

On the title page of the work is an engraved portrait of Sir John proudly sporting a fine oval-cased watch with the Harrington shield of arms engraved inside the cover. The portrait is dated 1st August 1591 and bears the inscription ‘Il tempo passa’ and the legend that Sir John was thirty years old when the portrait was taken – time passes and this is a moment in the life of the author.

A similar watch can be found in the British Museum collections, made by an immigrant Flemish worker in London, Ghylis van Gheele and here too, the watch sports a shield of arms, This time of the Giffard family of St. Andrew’s Abbey in Northamptonshire.

In late Elizabethan England what better way to show everyone just how wealthy and successful you were.

Power madness

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

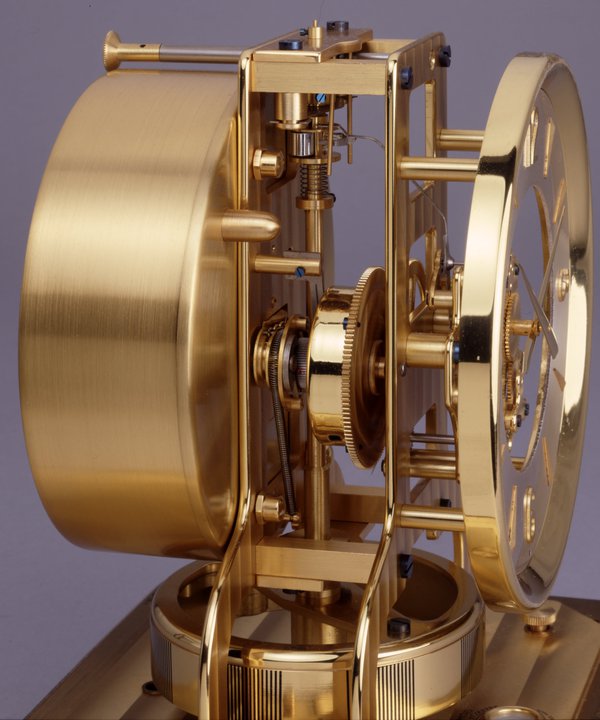

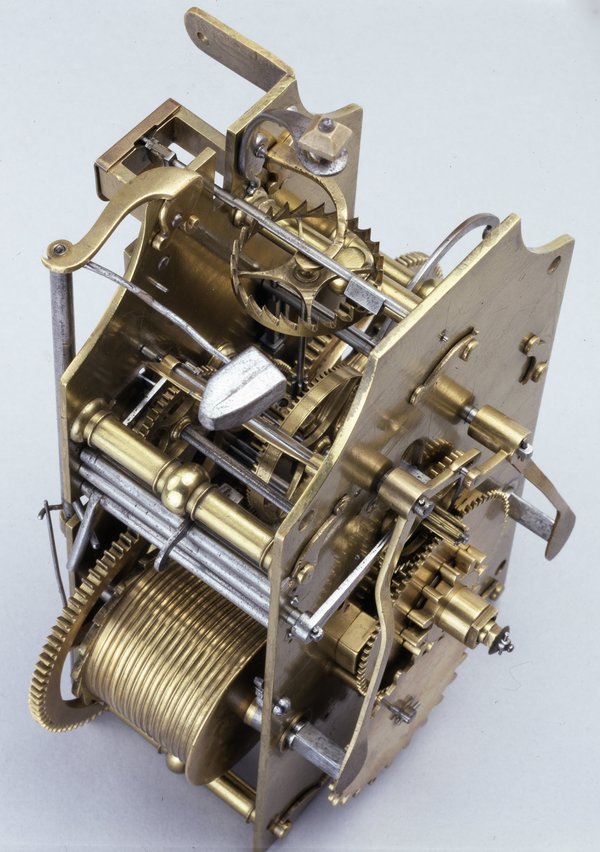

In a previous post I explained how mechanical clocks and watches work, with five elements – energy, wheels, escapement, controller and indicator. Let’s explore how some clocks and watches get their energy.

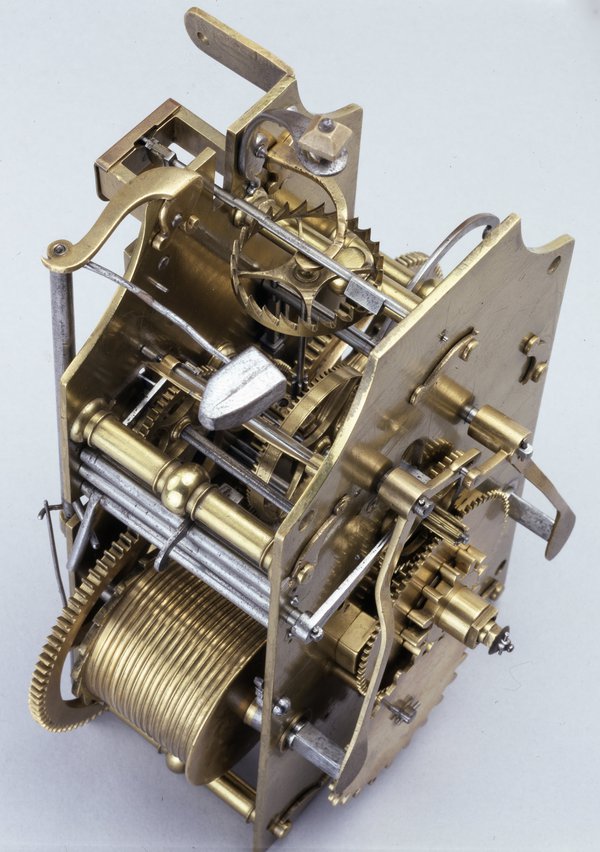

Mechanical clocks and watches employ kinetic energy, drawn from a built-in reserve – usually a mainspring (elastic potential energy) or a driving weight (gravitational potential energy). However, these need to be replenished, or wound-up.

We commonly wind-up a clock or watch directly, with kinetic energy from our muscles (which, before that, was chemical energy from our breakfast). In an automatic watch, a moving weight spins and winds it up as we move around.

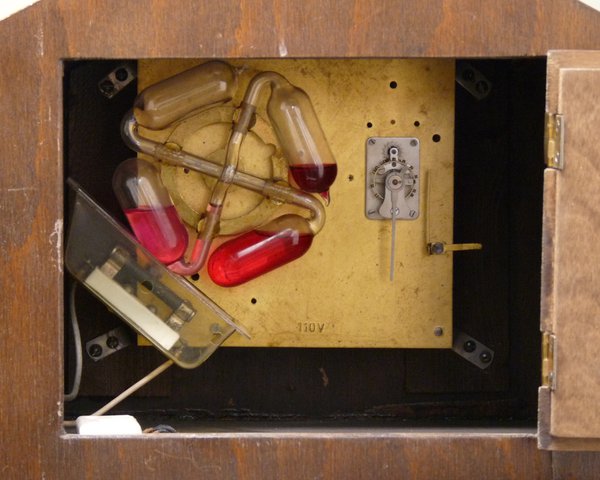

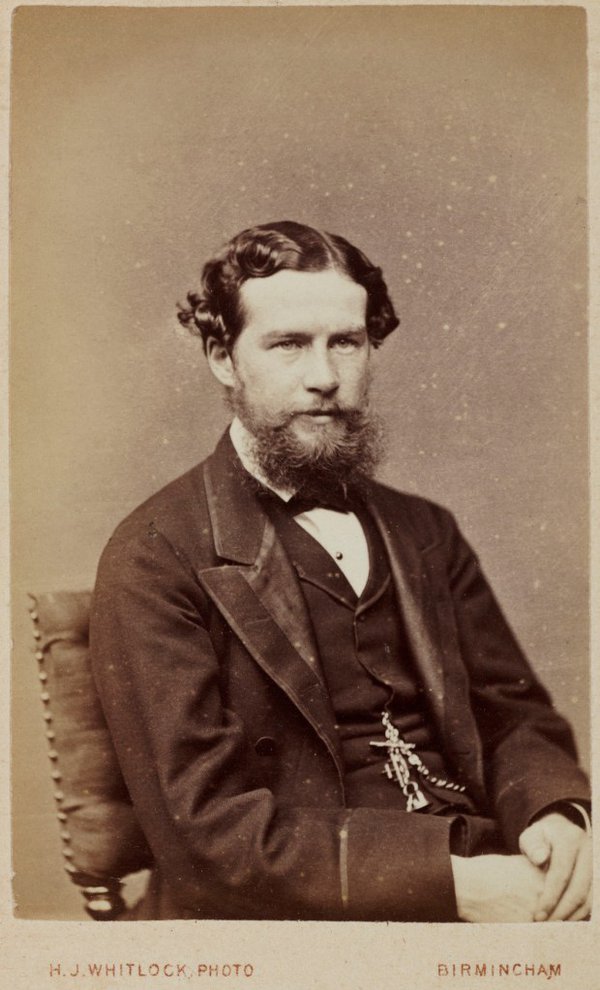

In c.1765, James Cox made a clock that is wound by changes in atmospheric pressure. Similar is the Atmos clock, which has gas-filled bellows which expand and contract with changes in the surrounding air temperature and pressure – this movement winds the spring in the clock. This has been a very successful design – it was first introduced in 1928 and it is still being made. There was even a mechanical clock made to be powered by by an artificial heat source (see image).

Electrical clocks and watches employ electrical energy. We might provide this by putting in a fresh battery (which is a reserve of chemical potential energy), although sometimes the battery is rather larger than the clock it powers!

Mains powered clocks often do not have a built-in energy reserve and so these are reliant on a continuous supply to keep going. Solar powered clocks and watches use solar panels to convert light to electricity, which then charges a battery – this reserve is essential as the power source is not reliable – e.g. day and night.

So, those are a few examples of how clocks and watches can obtain the energy they need. Of all the types of energy I can think of, only sound and atomic energy have not been not used to directly power clocks and watches. As to how they exploit the energy… well that is another story altogether… maybe for a later post!

It’s for the birds

This post was written by James Nye

Some pigeon racers were cheats. This was the shocking brief given to the Skymaster Clock team in the 1950s when refining their latest patent racing clock.

It was a serious business for the 100,000 registered pigeon fanciers in Britain, and rigid standards were enforced. Defeating the few cheats involved some inspired horology, and when I heard how clever the solution was, I wanted to share it here. But first, let’s understand the basics.

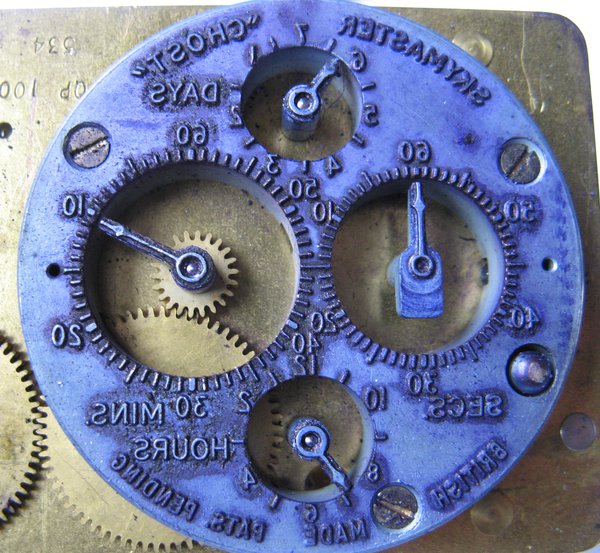

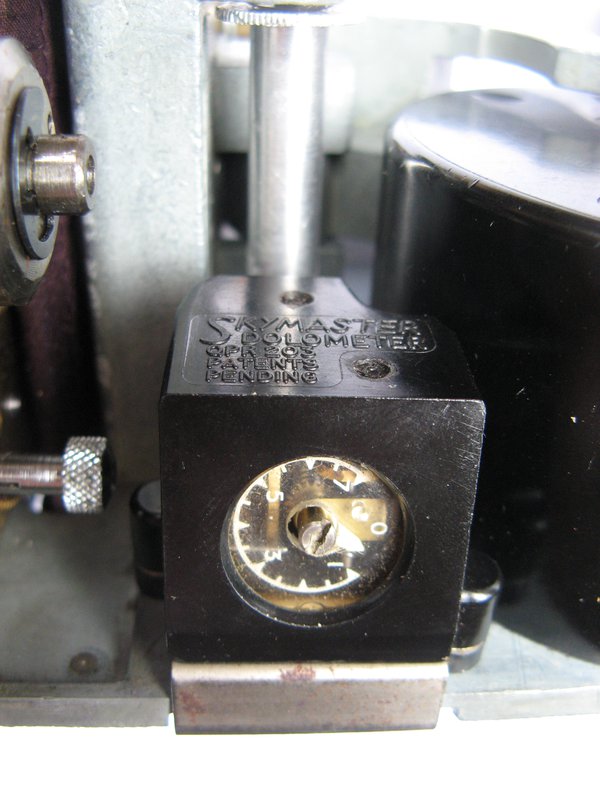

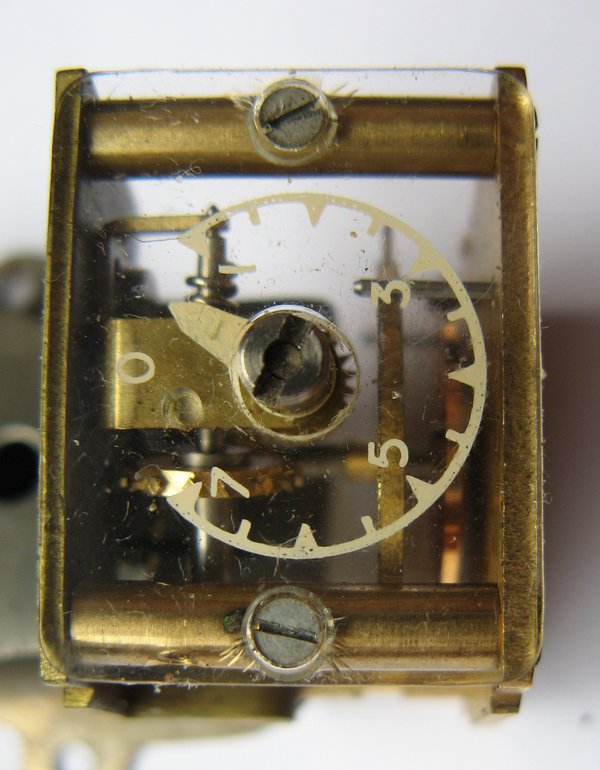

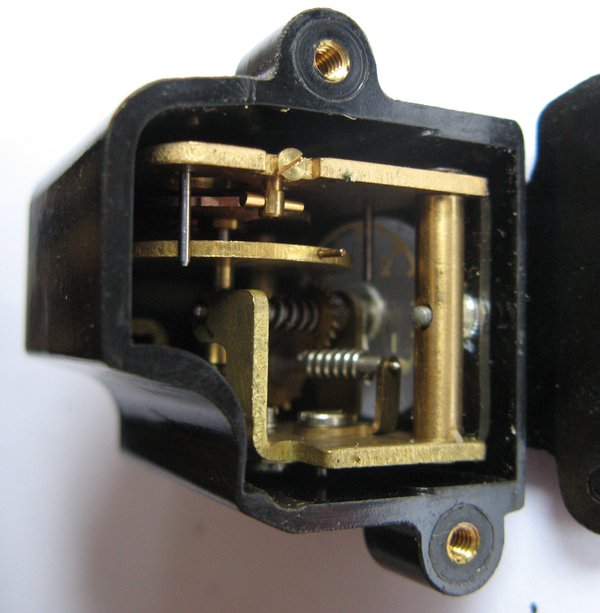

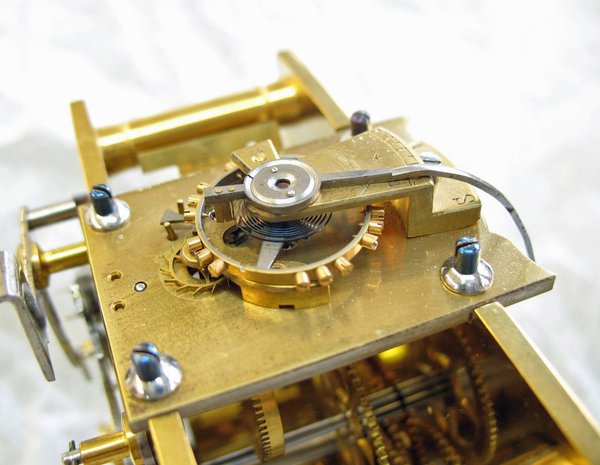

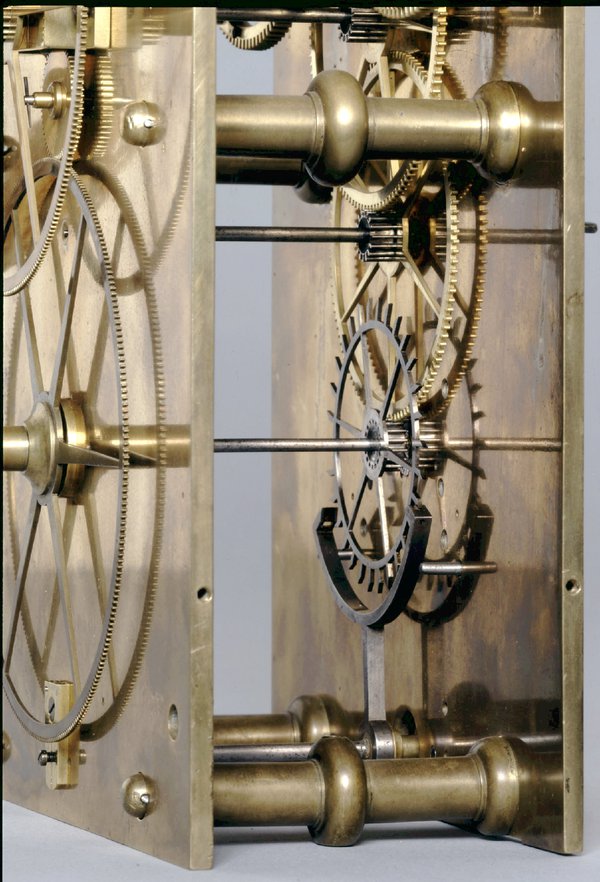

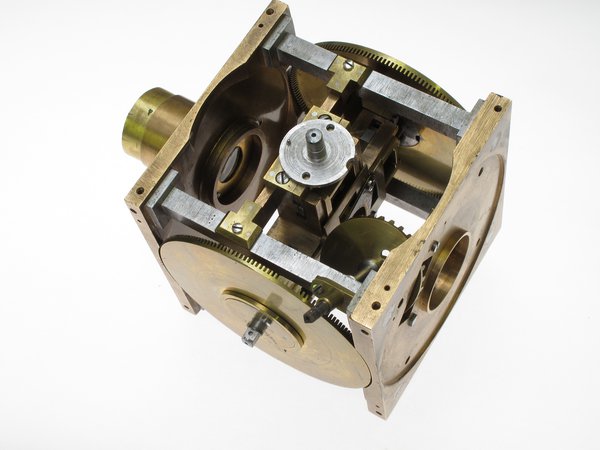

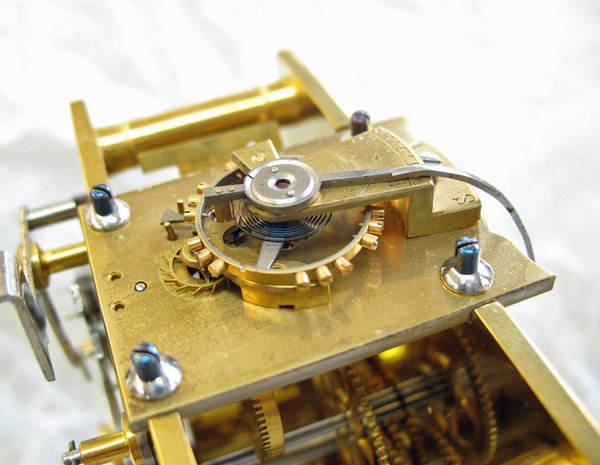

The Skymaster clock contains a 7-jewelled platform escapement movement, coupled to an inked ribbon stamping mechanism (like a time-recorder) which presses a paper tape against an internal mirror image dial (in relief), recording the time a returning pigeon’s identifying ring is inserted.

Races are won by seconds. Pigeon clocks are meticulously checked and every option to cheat is blocked. But unscrupulous fanciers had come to believe that platform escapement clocks could have their rates meaningfully altered, for example by swinging the clock in the same plane as the balance, so that they might both retard the locked clock (ideal before the pigeon arrives) and advance it (needed once the pigeon is back) to get it back to time before being examined by an official.

The effectiveness of these methods is uncertain but, nevertheless, Eric Moss and Bruce Alexander of Smiths were compelled to devise a brilliant solution for the Skymaster – called the ‘Dolometer’. They based it on an electro-mechanical car clock, in which typically an inverted-Sully escapement (electrically driven) advances the train. See an animation here. They removed the magnetic drive, and relied on the overall motion of the clock to drive the Dolometer – thus the dial reveals the degree of any shaking.

Calibrate for ‘normal’ activity (the natural joggling of a journey home to the loft, plus a margin for error) and if the Dolometer shows an excess, you have detected a naughty pigeon fancier’s attempted fraud. Bruce Alexander carried a dolometer for days – even cycled with it – to work out what a normal reading would be.

This seems to me to have been inspired thinking on the part of the designers. And it inspired me to acquire a Skymaster so that I could dismantle and photograph it for you.

Big Ben and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

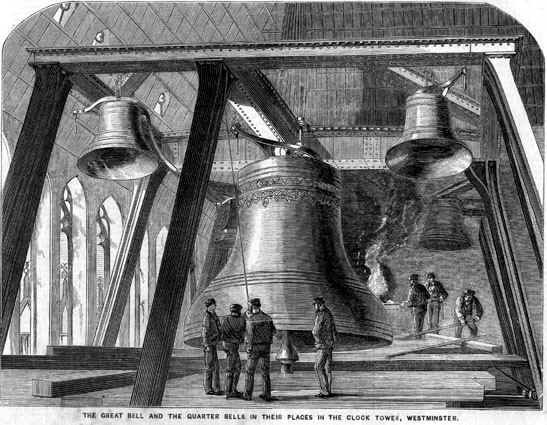

The iconic tower that houses the world’s most famous clock has always simply been known as the Clock Tower, but was renamed Elizabeth Tower to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. Will the name catch on? I think that the man in the street, and that includes the tourists, will continue to call it the Big Ben, even though that was never the name of the tower, just the nick-name of the hour bell.

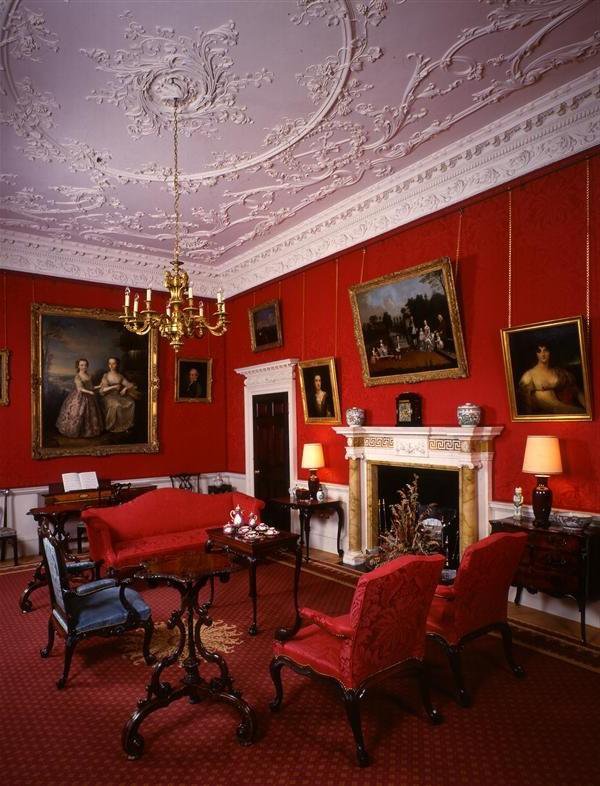

On 10 June I attended the launch of a guidebook published by the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and the Elizabeth Tower. It was great fun because it was held in the Palace of Westminster, in the opulent State Rooms in Speaker’s House, which outsiders don’t often get to see. The book is attractively produced and richly illustrated, and those wanting more can read Chris McKay’s book Big Ben. The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster.

Mr Speaker, John Bercow MP, addressed the guests, after which there were short talks by Mike McCann, keeper of the Great Clock, and Paul Roberson, one of the three clockmakers responsible for winding, servicing and repair of over a thousand clocks in the Palace of Westminster.

Between them, they also have to provide a 365 days a year out of hours call-out service should the Great Clock have a problem.

This illustrated article by Chris McKay reports on an overhaul of the Great Clock, undertaken in 2007 to correct wear problems. Paul Roberson, who is currently chairman of the British Clock and Watchmakers Guild, ended his talk with a joke that is probably as old as the hills but was new to me: 'What did Big Ben say to the Tower of Pisa? "I’ve got the Time, if you’ve got the Inclination".'

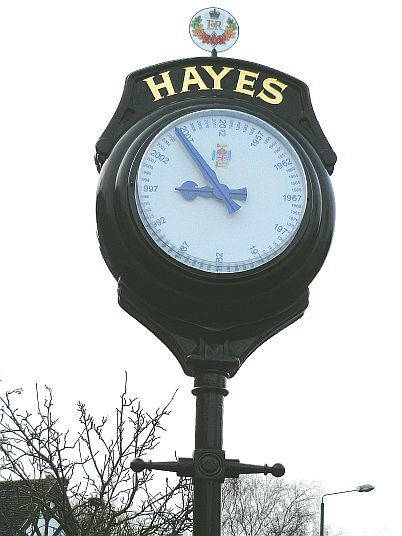

Elsewhere in the country the Diamond Jubilee has inspired modest horological activity. In February 2013 a jubilee clock was unveiled in Hayes in southeast London. The clock dial is made up of the sixty years of the Queen’s reign rather than minutes, with 2012 marking 12 o’clock.

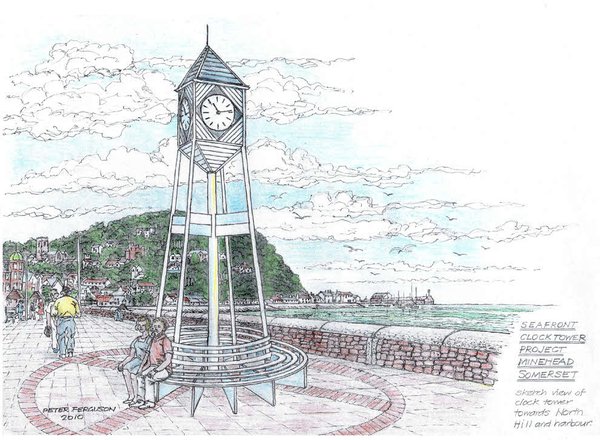

And in Minehead on the Somerset coast they hope to build an 8.5 metre tower with a four-sided display, with clocks on three sides and current tide times on the fourth. They still need donations to make it happen.

There will have been more initiatives. But it was nothing compared to the public clock ‘mania’ that erupted on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, which I shall discuss in my next blog.

Navigating the trackless seas

This post was written by David Rooney

If you stand on the Thames riverside near the East India dock basin, the view south is extraordinary.

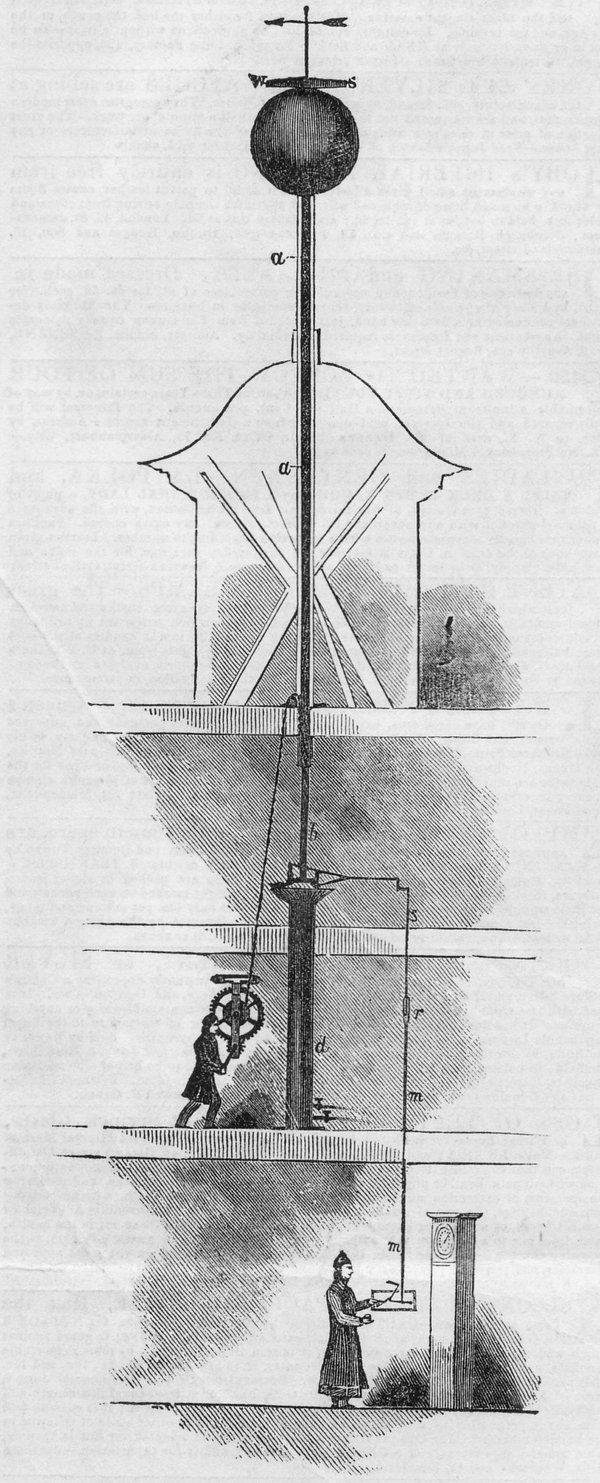

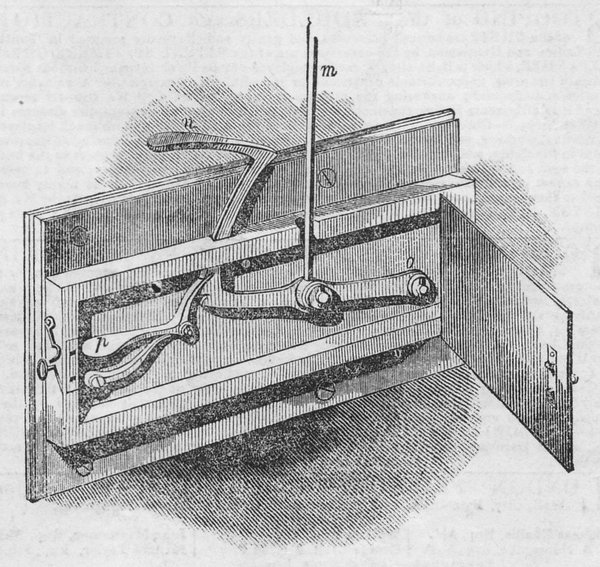

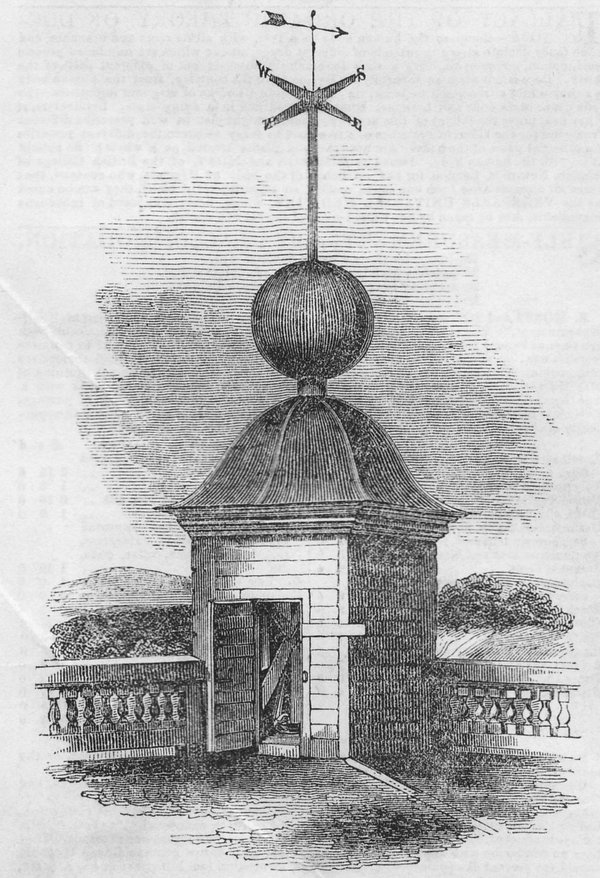

In the foreground is the remarkable structure of The O2, originally the Millennium Dome. But look further into the distance, and you’ll just make out the Royal Observatory perched atop the high reaches of Greenwich Park. Look even more closely and you will see the one of the world’s first public time signals fixed to its roof.

The Greenwich time ball has been a London landmark for 180 years, since it was first constructed in 1833. But it is more than just a tourist attraction. Until the early twentieth century it was a life-saving technological tour-de-force which enabled sailors leaving Britain’s busiest port to find Greenwich time to a fraction of a second – not for punctuality but for navigation.

Just over a decade after its erection, the Illustrated London News ran a major feature on this high-tech time-check.

'The keeping of true time is important to all persons', it observed, 'but to those engaged in navigating the "trackless seas", it is of such consequence, that the government … have not hesitated to expend large sums of money for its discovery, preservation, and announcement to the world.'

It is hard, today, to imagine this little cluster of modest brick buildings as a national centre for scientific excellence. But that is what it was.

As the newspaper explained, 'from the beauty of the instruments, the exactitude of the observations, and the high scientific ability of the officers engaged, the once difficult problem of finding the precise instant when one o’clock touches the world’s history, is no longer a matter of doubt or difficulty.'

We’ve developed other ways to know the time since 1833, but the ball still keeps dropping, and if you wait patiently on the riverside at East India with a pair of binoculars, you can still observe the precise instant of one o’clock every day.

Want to know more? Set your calendar for what promises to be a superb AHS London Lecture by Douglas Bateman on 19 September. See the website for details nearer the time.

‘I didn’t see him take anything, but they’re not here now’

This post was written by David Thompson

'Lost out of Mr. Garon’s shop on Monday the 14th instant, a gold watch, hook chain and seal all gold, on the dyal plate Garon London, one silver watch the name Garon London, another silver watch the name Clyet Landon: If the said watches be brought to be sold, pawn’d, valued or amended, you are desired to stop the goods and party, and send word to Mr. John Milburn a watchmaker in the Old Baily, and you shall have 6 guineas reward or proportionable for any part, or if brought to the said Mr. Milburn, the party shall receive 6 guineas, and shall have no questions asked'.

Politicus Mercurius, London, 17th-19th November 1709

Advertisements such as this are common in the London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne (1703-1714) and every one tells a tale. Just what happened here where Mr. Garon had three watches stolen from his shop we don’t know, but by any account the event was unfortunate.

Whilst this watch by Peter Garon is not the gold one described, there is no doubt, judging from this example, that a Garon watch was not something anyone would want to lose. The tortoise-shell (turtle) outer case inlaid with gold wire is a work of art in itself.

Peter Garon was a Huguenot who was formerly known as Pierre Garon and he had something of a chequered career. Brian Loomes in Early Clockmakers of Great Britain gives the following account.

Peter Garon was apprenticed to Richard Baker in April 1687 and finished his term in 1694. However, because he was still an alien, he was refused freedom by the Clockmakers’ Company but the Lord Mayor of London did grant that freedom in the same year. He became a Freeman in the Clockmakers’ Company in August 1694.

In October 1696 he admitted forging the name of a Mr. Legrand on a watch of his own making. In 1697 he was warned about taking unofficial apprentices and by 1709 he was clearly in trouble again.

'Whereas the acting Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt awarded against Peter Garon of London, watch-maker, have certified to the Right Honourable the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that the said. Peter Garon, both in all things conformed himself to the late Acts of Parliament made against Bankrupts: This is to give notice that his certificate will be confirmed as the said Acts direct, unless cause be shewn to the contrary on or before the 2d of March next.'

London Gazette 7th-10th February 1709

Note. We are hugely indebted to W.R. and V.B McCleod and John R. Milburn (no relation to the above) for their researches into the lost watch advertisements in London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne.

Do clocks tick you off?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

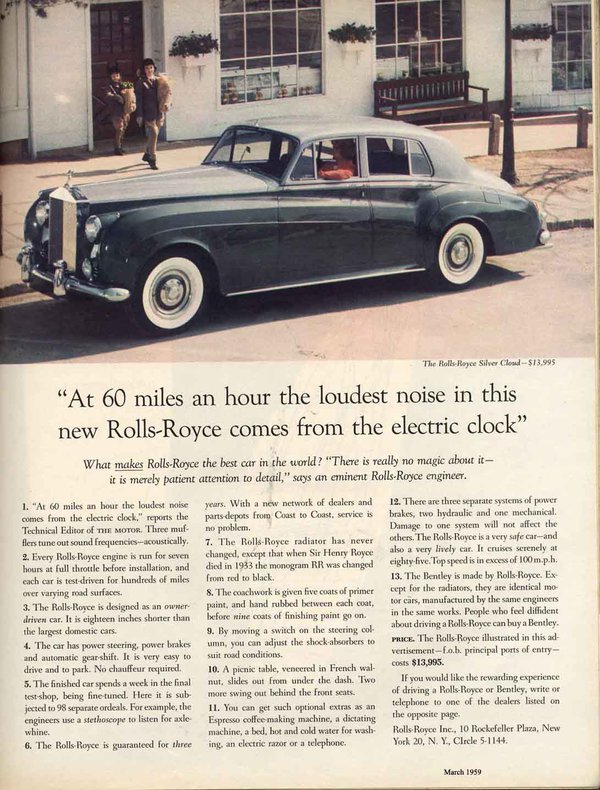

In his book Confessions of an Advertising Man, originally published in 1963, David Ogilvy calls this ‘the best headline I ever wrote'.

Interestingly, in a footnote he adds: 'When the chief engineer at the Rolls-Royce factory read this, he shook his head sadly and said “It’s time we did something about that damned clock!"'

I previously explained that the ticking of a timekeeper is the sound of the escapement stopping a wheel tooth. But why is the ticking of a clock music to some and unbearable to others?

Loudness is a common complaint. The farther and harder the tooth drops before it is stopped by the escapement, the more energy is lost to sound and the louder it will be. This will tend to increase with size, but energy loss can be minimized with an efficient design and good construction. Also, the rest of the movement and its case can act to either attenuate or amplify the sound.

The timbre of the sound can be soothing or grating. Just like the character of a violin is much more than the pure tone of its vibrating string, we are not hearing just the escapement – the construction of movement and case all contribute to the texture of the sound.

Another aspect is the timing of the ticks – the beat of the clock. An uneven beat probably offends everybody. If, instead of an even 'tick tock tick tock tick tock', you hear 'ticktock… ticktock…. ticktock…' (or even tocktick!) then your clock is out of beat. To fix this, make sure the clock is level, otherwise your repairer can easily sort it.

Some examples:

Some clocks were designed to reduce escapement noise. Some of these had so-called 'silent escapements' in which more compliant materials were used (such as spring steel and gut line) to absorb the impact. Pietro Tommasi Campani invented an impact-free crank escapement for use in his night clocks.

Avoiding escapements altogether, compartmented cylindrical clepsydrae were recurrently popular at various times in history. In quartz controlled clocks, the escapement is also eliminated, although many of those use physical hands whose driving motors can usually be heard, ticking or whirring.

Thanks to Peter de Clercq for inspiring this post and providing the piece on Ogilvy.

A telescope by Henry Hindley

This post was written by Tim Hughes

The work of Henry Hindley of York was researched by Rodney Law and published in Antiquarian Horology (1971/2). The article describes two equatorially mounted telescopes signed Hindley.

The first of the two telescopes forms part of the collection of the Burton Constable Foundation, East Yorkshire, and the later instrument is now in the collection of the Science Museum London.

In recent months, the earlier instrument (circa 1740) has been through a process of conservation cleaning and close study by Tim Hughes of West Dean College.

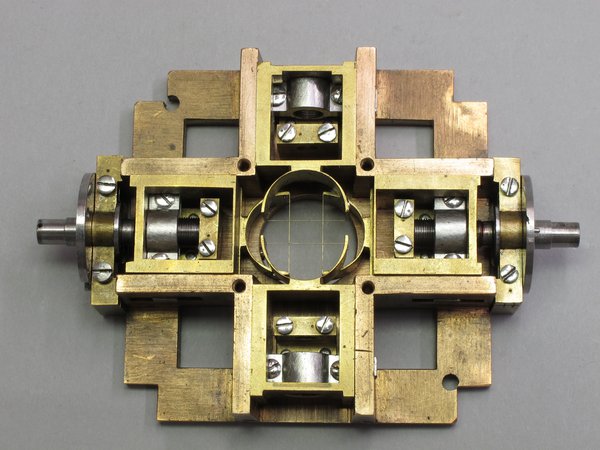

The instrument is regarded as of significance and is known to have been purchased by William Constable for use in the eighteenth century observations of the Transit of Venus. The telescope mount bears much resemblance to that by James Short published in Philosophical Transactions in 1760, having meridional, equatorial and declination circles over a primary setting circle.

Interestingly, Hindley’s telescope mount is a combination of sound mechanical clockmaking practice – including the very precise and beautifully made worm gearing – and surprisingly unstable telescope mount which raises questions about the development process and Hindley’s involvement with the various stages of manufacture.

The instrument is signed on the micrometer box only, which is in itself a piece of clockmaking genius. Within the box are fitted four reticule frames, connected by intermeshing contrate wheels operated by a setting knob. The reticules form an adjustable square frame within the field of vision allowing angular measurement of the size or distance between objects.

Work on cleaning and recording the instrument is almost completed and has been assisted by Charles Frodsham and Company Limited who have kindly carried out measurement of the gearing of the equatorial circle and its driving worm.

Once re-assembled, we intend to carry out field tests with the help of a professional surveyor in order to better understand the calibration and range of the instrument which may further inform its purpose and limitations. A paper giving a technical description of the construction of the instrument to appear in AH in due course!

Enicar will do

This post was written by James Nye

Collectors of Enicar watches may be intrigued by a story I recently uncovered.

The life of this popular Swiss brand (1913–1988) took in two world wars and the quartz revolution of late 1960s. The name Enicar derives simply from reversing the family name of the owners, Ariste and Emma Racine. Starting with movements from Schild, the couple expanded Enicar operations with a large manufactory in Lengnau (in Biel) after the Great War. The history of the firm is summarised here.

Ariste (junior) took over in 1938, and had to steer a cautious path through the Second World War. Some firms supplied both German and Allied clients, but we have some insight into Ariste’s sympathies through the extraordinary story of Major P. Oldfield, a wounded prisoner of war in Italy, who escaped to Switzerland, where he was in and out of hospital.

As part of his convalescence, he trained in simple clock assembly, developing an ambitious business plan with Ariste. After repatriation in 1944 to the UK, Oldfield helped his partner travel to London to seek permission for an alarm clock factory in the UK.

Racine had tried the scheme before, in 1939–1940, with the Clerkenwell firm of Robert Pringle & Co, but Edwin Pringle died in 1942, and in 1944 Racine used Oldfield as a new conduit to the Board of Trade to revive the idea, with a view to importing machinery from Switzerland, at first to assemble imported parts, but ultimately to manufacture alarms.

The British government was keen on schemes that could employ wounded ex-serviceman, and Oldfield was the walking advertisement. From alarms, Enicar UK would graduate to watch production.

The scheme did not progress, probably owing to resistance from the UK trade, perhaps hostile to competition from a Swiss national proposing to set up production without government subsidy. But the project interested the British government for some time in 1944–1945, and the file (BT 64/3661) at the National Archives would prove rewarding to the serious Enicar enthusiast. By all means contact me for help.

Horological horrors

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

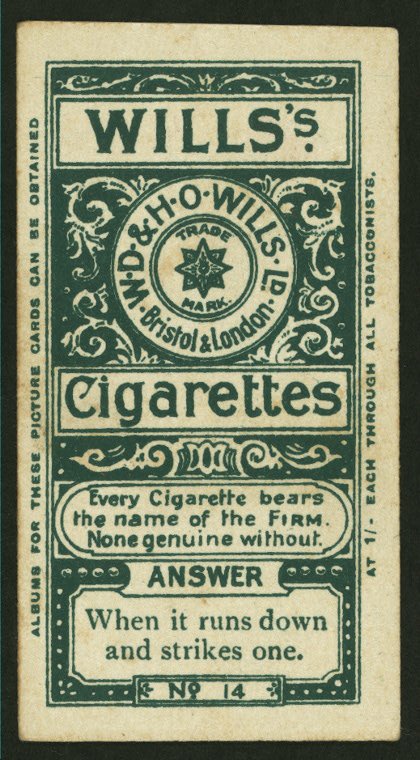

Browsing the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library I found a collection of cigarette cards, issued by tobacco manufacturers as an added incentive to buy their product.

On one of these cards we see a drawing of a longcase clock (the tall, standing type also known as grandfather clock) on a landing, with a riddle: ‘When is a clock on the stairs dangerous?’ The answer is printed on the back of the card: ‘When it runs down and strikes one’.

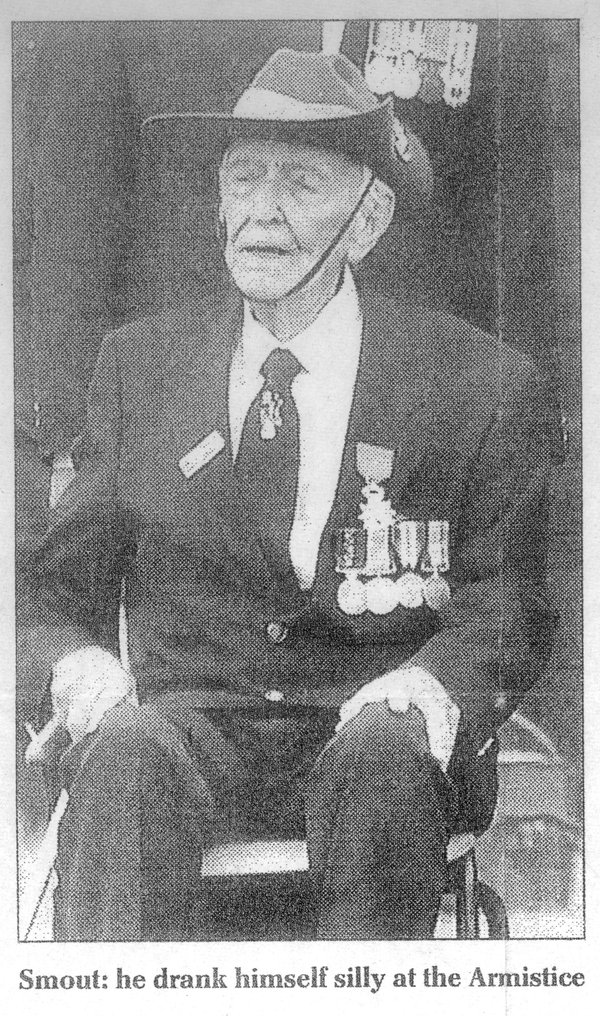

Jokes aside, longcase clocks can be dangerous, as one of the last Australian survivors of the Great War found out. When he died aged 106, the Daily Telegraph obituary had this lurid detail: two years earlier he had become trapped under his own grandfather clock when pulling up the weights. What an unexpected assailant for a veteran soldier! An AHS member sent me the clipping, after a neighbour of his had had the same misfortune. The lesson: make sure your longcase clock is firmly fixed to the wall.

Of course, there may be situations where you simply don’t have time to do that.

In his latest monthly column ‘Diary of a clock repairer’ in Clocks Magazine, Robert Loomes writes how he delivered a restored grandfather clock to a house in the countryside. Just as he finished setting it up, a squirrel ran into his trouser leg (you couldn’t make it up). Quite understandably, he stumbled and fell, and the assembled clock was dashed to pieces.

In September 2010, an AHS member in the Canterbury region in New Zealand wrote to me: ‘It was a sad day for unsecured longcases last Saturday. There was a major earthquake in Christchurch and at least two friends who had yet to screw new acquisitions to the wall had them tossed across the room and smashed.’

At my request, he wrote a short piece about it for the journal, and supplied a photo of one of the damaged clocks. Sadly, five months later a second, more destructive earthquake hit Canterbury, causing massive destruction and killing 185 people. In that light, it would have been insensitive to print the piece about damaged clocks. Fortunately I could just withdraw it before the journal went to the printer.

Happy St Lubbock’s Day

This post was written by David Rooney

If you live in the UK or the Republic of Ireland, I hope you enjoyed the bank holiday earlier this week. Perhaps you went with family or friends to one of the many great museums with horology collections.

For bank holidays we can thank the remarkable Victorian polymath, John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury), who was the subject of a fascinating Royal Society conference I attended recently.

Lubbock is usually associated with the preservation of Britain’s ancient monuments such as Avebury. In 1882 his landmark Ancient Monuments Act was passed. But this was not nostalgia – Lubbock believed the relics of the past helped us understand our own progress, and he was about as modern as you could get in the late nineteenth century.

It was in electricity that Lubbock truly blazed a trail, a story I’ve recently been researching. Many in the AHS are interested in electrical timekeeping, a subject with more than a century and a half of history, and the place of the electrical industries in this story is crucial.

In 1882, the same year that he guided his ancient monuments bill to completion, Lubbock also sponsored the Electric Lighting Bill, and became a director of Thomas Edison’s offshoot company formed to bring electric lighting to Britain. His firm financed and founded the world’s first public electric power station, on Holborn Viaduct, and the following year he steered through the merger of Edison and Swan, Britain’s two pioneering electrical companies.

Lubbock once gave a lecture praising the work of William Cooke, Charles Wheatstone, Alexander Bain and Louis-Francois-Clement Breguet, amongst others. Electricians, yes, but horologists too.

So if, on your bank holiday museum trip, you saw clocks by any of the electrical pioneers, it is worth thinking of the role John Lubbock played in creating the modern electrical world – and in creating a world that values the relics of the past. And you can also thank him for giving you the day off.

Japanese time

This post was written by David Thompson

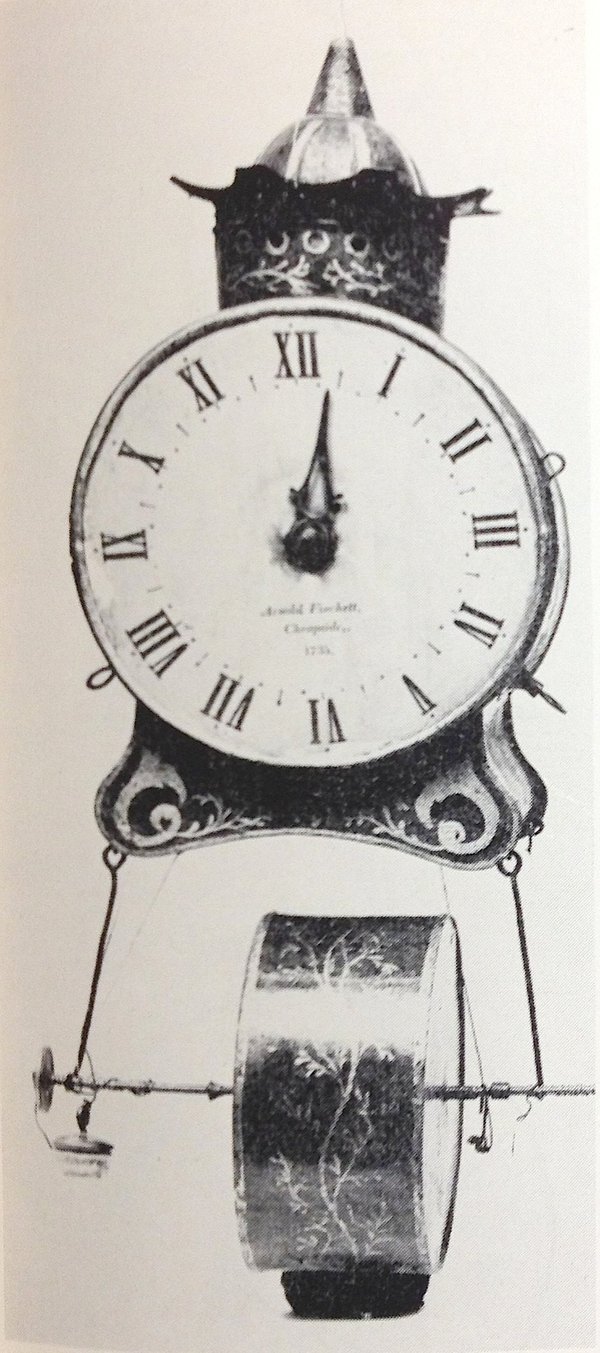

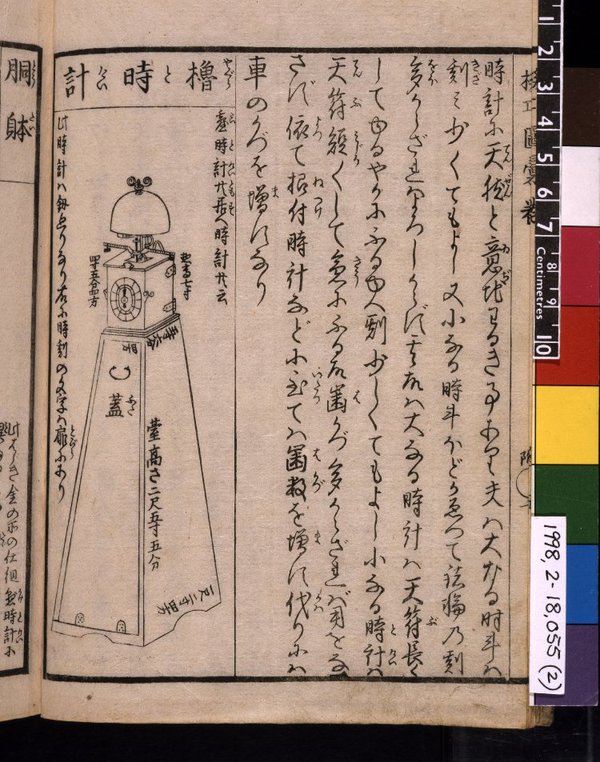

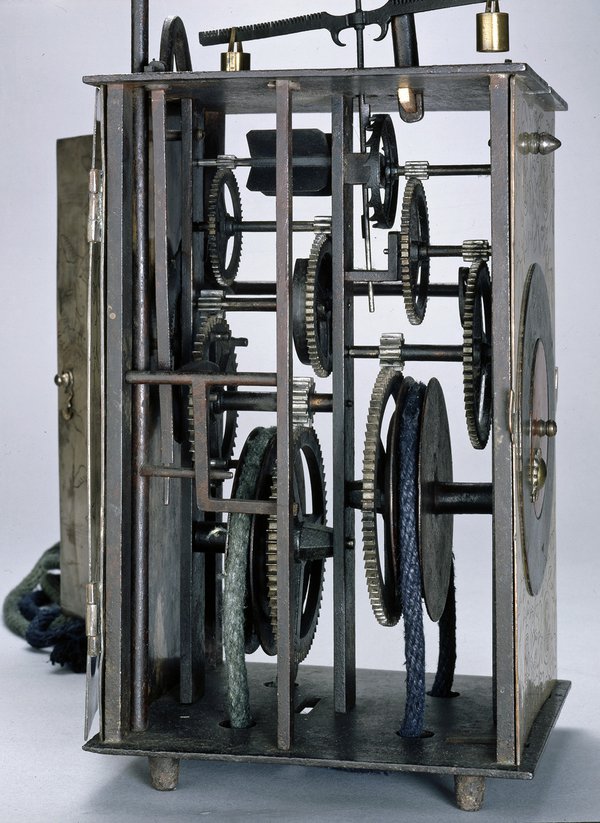

From the first appearance of the clock in Japan, when the Spanish Jesuit priest, St Francis Xavier, arrived with gifts for the Emperor, including at least one clock, in 1551, the story of mechanical timekeeping in that country has been an intriguing one, and one which lasted until the end of the Edo dynasty in 1873.

From 1612, when the Europeans were expelled from Japan and the country was closed to outside influences, the Japanese clockmakers were on their own for over 250 years. What they produced in terms of clocks was indeed ingenious.

First of all, how was time measured in Japan in that period? Take the hours of darkness and divide those up into six equal parts. Then take the hours of daylight and also divide those up into six equal parts and there you have it. Clearly if the day is divided in this way, the length of the daylight periods and those of darkness will vary throughout the year except at the equinoxes when all the hours will be equal and equivalent to two hours of European time.

Unfortunately, mechanical clocks like to keep equal unchanging hours as best they can. So, what did the Japanese clockmakers do in circumstances where they had no access to what was going on in far distant Europe at the time?

Three quite effective methods were devised to get round the problem:

- to have two separate oscillators in the form of weighted swinging bars known as foliots with adjustable weights to change the rate of the clock.

- to have moveable markers either on a round dial or on a flat bar, depending on the type of clock.

- to have a series of plates, usually fourteen, which would be changed periodically depending on the time of year.

In all three types the time indication would have to be adjusted twice per month.

When it came to style, there were basically three types of clock in Japan:

- the stand or lantern clock, weight-driven and either mounted on the wall or placed on a stand.

- the table clock, designed to be placed on tables or on a suitable place in an alcove.

- the pillar clock, specifically made to hang on the thin wooden pillars which made up the framework of the inner paper wall of the house.

In the early period, the oscillating foliot was used as the timekeeping element, a single one in the earliest clocks and a double in the later, more sophisticated examples. As the technology progressed, pendulums or oscillating spring balance wheels were used – a larger form of the device found in mechanical watches.

Such clocks were only owned by the wealthy and were perhaps more used as status symbols than they were to tell the time and organise the household.

The basics – how a timekeeper works

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Old clocks and watches are fascinating even without knowing how they work, but just a simple explanation provides a much deeper appreciation.

The timekeeping function of mechanical timekeepers can be explained as just five elements:

1 – Energy Source

All machines, including timekeepers, need energy to work. The energy is usually stored in a weight or spring. When it is wound, energy is transferred from our muscles and into the driving weight (as it moves up against the force of gravity) or the mainspring (as it tightens-up). This energy is released into the timekeeper as the weight drops or the mainspring unwinds.

2 – Wheels

An interconnected series of toothed wheels and pinions, known as a train, transmits the energy through the timekeeper. The energy source moves slowly and the wheel at the furthest end of the train moves quickly. This is the opposite of a car gearbox, where the engine revs quickly and the wheels on the road rotate more slowly.

3 – Escapement

The escapement is connected to the quickly moving end of the train of wheels. Like a turnstile which allows one spectator through at a time, the escapement allows one wheel tooth to pass through (or 'escape') at a time. Without it, the wheels would whizz until the weight hit the floor. The ticking of a timekeeper is the sound of the escapement stopping a wheel tooth.

4 – Controller

The controller is connected to the escapement – it controls the rate at which it allows the teeth to pass through. As each tooth passes the escapement, it gives the controller a little push to keep it going. A common controller is a pendulum, which is just a hanging weight – give it a push and gravity makes it swing, at a steady rate. Because gravity is very constant, pendulums are great for good timekeeping.

5 – Indicator

The part of the timepkeeper that tells us the time. Most familiar are hands on a dial. A clock striking a bell gives an aural indication of time – sometimes from many miles away.

These five elements apply to (almost!) all mechanical timekeepers from the most ancient to the modern. They can vary wildly, but are there if you look!

PS This superb website has interactive animations showing how escapements (and some other horological bits) work.

King’s Cross – March 1952

This post was written by James Nye

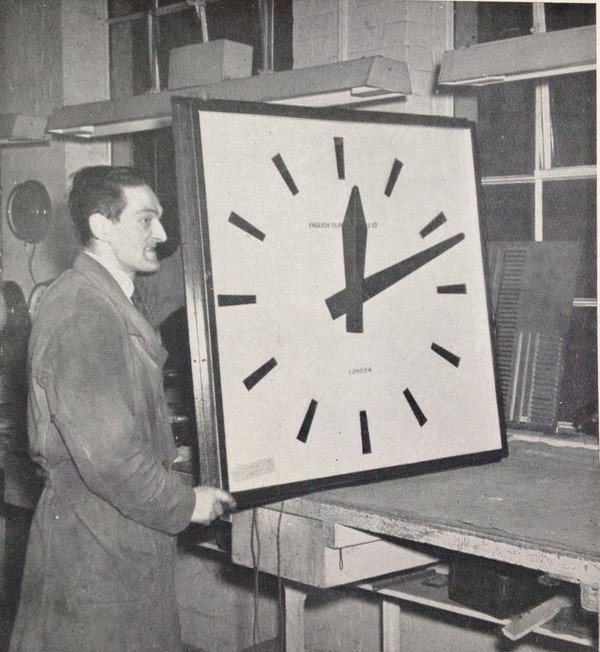

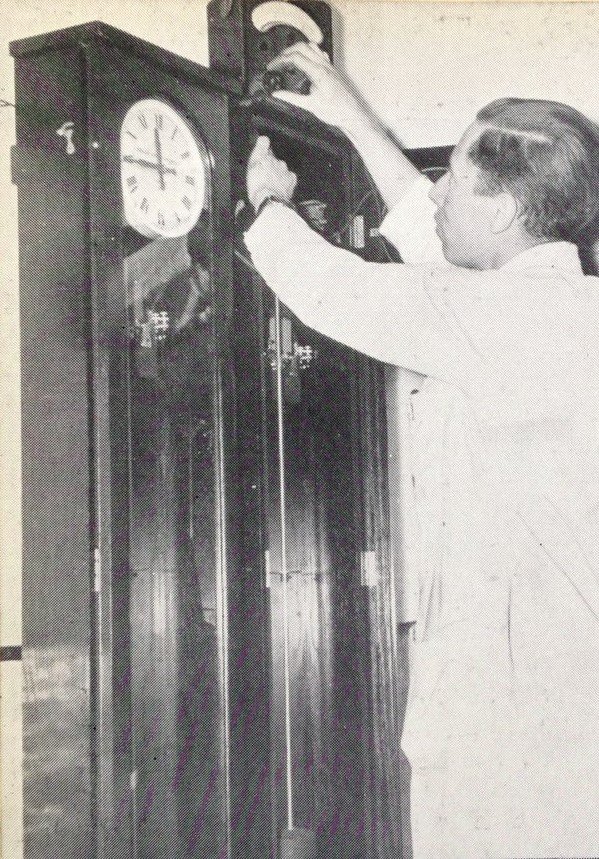

I am spending every waking minute at present researching and writing about Smiths, owner of the English Clock Systems marque (ECS). Just now I came across an article about ECS in the March 1952 in-house Smiths magazine, and thought it worth sharing some of the accompanying images.

Based on surviving clocks, ECS is perhaps now best known for: a range of master and slave clocks, similar in concept to the Synchronome; synchronous public clocks; and process timers (e.g. darkroom clocks), which often turn up on eBay.

I don’t think any pictures of the inside of the original ECS works on Wharfdale Road, King’s Cross, have been published in a long time, so here we go, with a small selection.

The first shows Reg Boskett, showing off a modern clock dial for exterior use. In the next shot, Dolly Etheridge is shown operating a capstan lathe – Dolly joined the firm in 1942, and was also a competition dancer!

The firm’s original business focused on importing and installing Ericsson time recorders, but little is reported of the time recorders manufactured in fairly large numbers by ECS all the way through to the 1970s. Another shot shows Jimmy James, an old-timer from the firm’s beginnings, in the time recorder department, with an array of movements.

The final shot shows the most sought-after object, the ECS master clock, in the main assembly shop, with Jack Horsfall, foreman, using his Avometer to set-up the series resistance.

At the time all these pictures were taken, the firm still had a successful future ahead of it, but in less than thirty years its market was eroded, and it was absorbed by Blick in 1980.

Martin Ridout, webmaster for the AHS, is also our resident expert on the English Clock Systems (ECS) marque. The current state-of-the-art knowledge appears on his web-site and is distilled in two technical papers published by the society’s Electrical Group, Nos. 68 and 82.

Click here for details of the group and a full index of its papers. With luck, my continuing research will throw up some more flesh for Martin to add to the tale.

What became of the London sundial column?

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

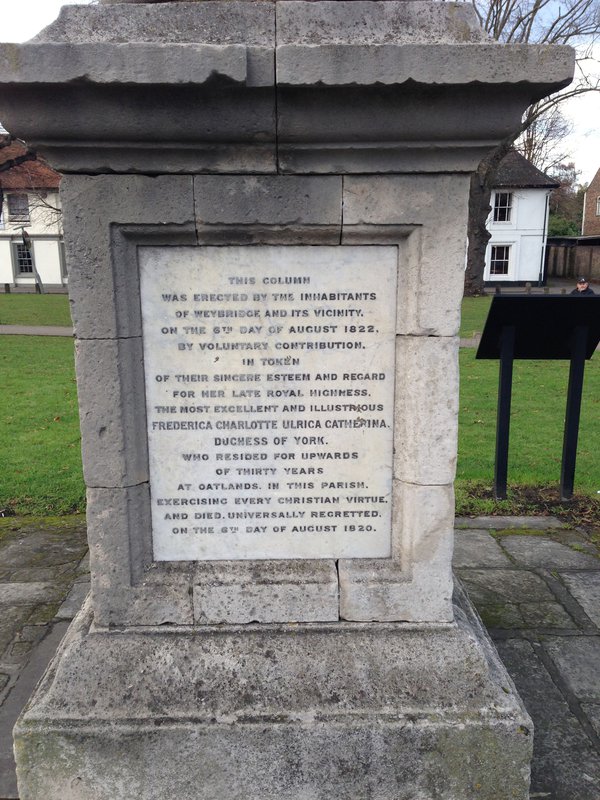

My previous blog was about the sundial column at Seven Dials in central London. It is a reconstruction, erected in the 1980s to replace a column that had been there since 1694 but was taken down in 1773.

Popular legend has it that it had been ruined by a search for treasure presumed to be buried under it. Perhaps more truthful is that it was removed because the place had become a meeting-point for riff-raff. Whatever the reason, it was demolished and its remains landed in an architect’s garden in Addlestone, Surrey, southwest of London.

But fifty years later it was given a new lease of life in nearby Weybridge. The column was erected by public subscription in 1822 in memory of Frederica, the Duchess of York (1767-1820) who had been a popular local benefactress. It was decided that the dial stone was too heavy to cap it. A ducal coronet was used instead and the base inscribed to the Duchess. Two centuries later, the York Column at Weybridge still stands on what is named Monument Green.

The original late 17th-century dial stone was used as a mounting block, to help the young or elderly or infirm to mount and dismount a horse or cart – not the best way to preserve a finely sculpted object. But this too has survived. More than three centuries old, and much the worse for wear, it lies to the west side of Weybridge Library. A plaque explains the historical significance of what to the average passer by must seem a very unassuming bit of stone.

My thanks go to AHS member Hugh Cockwill who lives nearby and took the photos at my request.

Time for everyone

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1947, the British chronicler of timekeeping, Donald de Carle, wrote the following tribute to American engineer Warren Marrison: ‘it is to him we are indebted for the most accurate timekeeper in the world.’

Marrison worked at the Bell Telephone Laboratories with J.W. Horton. And in 1927 they had made the first quartz clock. It was a game-changer.

The electric clock pioneer Frank Hope-Jones sought to calm fears about the new technology, explaining in 1944 that ‘There is no reason to be afraid of the quartz clock. The trick whereby the vibration of a resonator can be maintained by a vacuum tube – the triode valve of our radio set – is easily learnt.’

He was right. By the end of the Second World War, Britain’s national timekeeping service was based on quartz clocks and today the technology underpins most modern time measurement.

But I think the quartz clock was more than just a new technology. It was one of a series of twentieth-century innovations that represented a new scientific politics, presented publicly as an alternative to nationalism that was ripping the world apart at the time.

If you want to know more, and to contribute to the debate, you might be interested in ‘Time for Everyone’, an international symposium being held at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, on 7 – 9 November this year. I’ll be there speaking about quartz clocks and the public politics of science, but if that’s not to your taste, you’ll also be able to hear other AHS speakers including Chris McKay, Jonathan Betts and James Nye, as well as a host of fabulous presenters from around the world.

The dog watch

This post was written by David Thompson

Anyone with connections with the sea and ships will tell you that the dog watch is a period of service between 4.00pm and 8.00pm and that it is split into two watches, the first and second watches on board ship.

Today there are any number of charms for bracelets and pendants in the form of dogs and I don’t doubt that there were all sorts for sale at the recent Crufts dog show. How many would guess, however, that you could buy a watch in the form of a silver dog in the 17th century.

A unique example exists in the British Museum collection where a silver-cased watch in the form of a dog can be found. The watch maker was Jacques Joly who lived in Geneva between 1622 and 1694. He made this watch in about 1660. It was during the middle period of the 1600s that there was a fashion in watches looking like real and animate objects, tulips, fritillary flowers, sea urchins and so on.

If the little dog needed a friend, there is a charming little lion living in the collections in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, this one with a movement made by Jean Baptiste Duboule. Of interest to both the dog and the lion is a little cast silver watch in the form of a hare which was stolen some years ago from the Musée de L’Horlogerie in Geneva. It has a movement inside signed, P. Duhamel, Geneva, and, as far as we know, a unique example of a watch case in that form.

Where can I see antiquarian horology?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

I refer not to our society’s journal (which you can of course see by joining us!), but where can we see old clocks and watches?

I clearly remember dearly wanting to know this information when I first became properly interested in horology. Now I am in the loop and am l pleased to be able to share some good tips.

There are the major collections in national museums; the British Museum, the Royal Observatory Greenwich and the Science Museum. But since these are well-known, let their plugging end there for now and let instead us look at a couple of less well known collections from different ends of the country.

Starting down South, there is the finest private collection outside the institutions mentioned above – the Harris collection, in Belmont House in Kent. The collection is wide ranging with examples from all the major clock making countries and periods, but there is a strong focus on England’s horological ‘Golden Age’. Not only does the house have its collection, but it is a beautiful place to visit in its own right – it is a magnificent neo-classical house set in beautiful gardens in the North Downs.

So, if you have a partner who likes horology a little less than you, they will not be disappointed when joining you on a visit there. Jonathan Betts, sometimes author on this very blog, conducts a clock tour at 1.30 pm on the last Saturday every month during the season. Prior reservation is necessary – please see the Belmont House website for details.

Now, heading up North, another great place to visit is Fairfax House in York. Fairfax Houses houses the collection of Noel Terry (grandson of the founder of the confectionery firm), one of the finest private collections of the twentieth century.

Again, this House has much more to offer than just clocks and watches and of course it is bang in the middle of York, a city worth a visit in its own right. The house is open every day except Mondays for most of the year – do check their website.

There are more collections to tell of, which can follow in a later post. Keep reading!