The AHS Blog

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

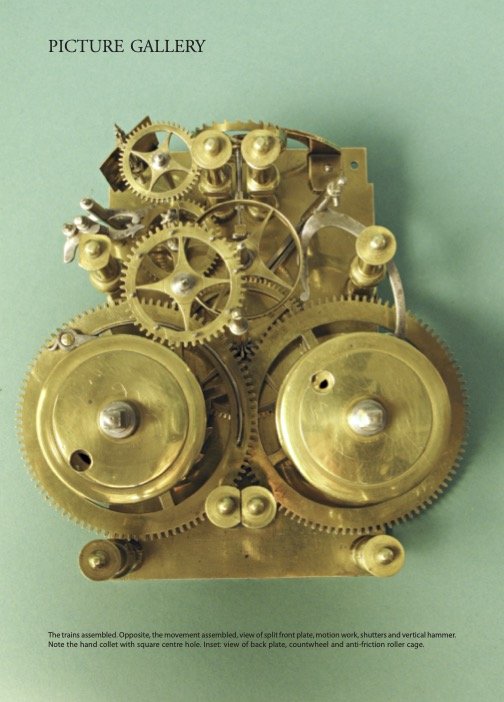

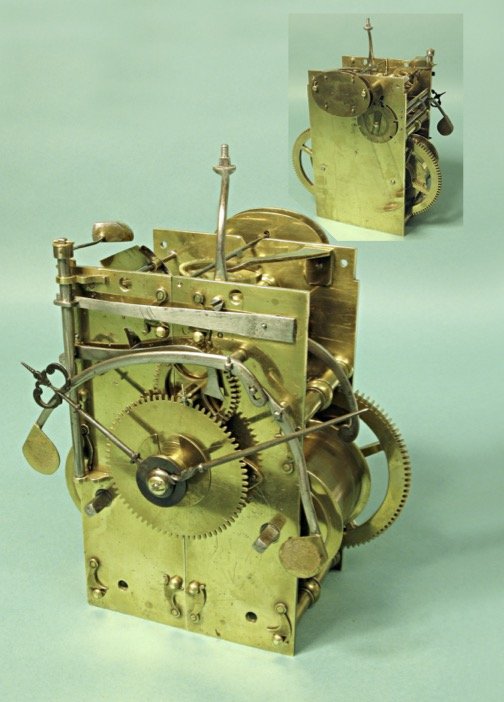

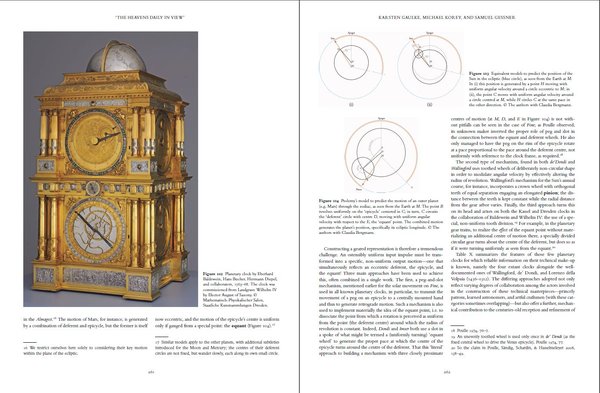

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Light among the lanterns

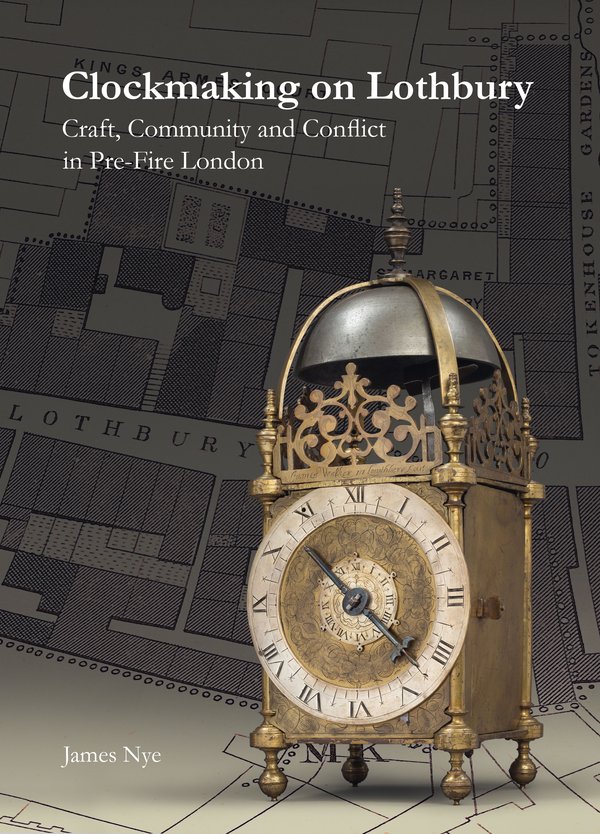

This post was written by James Nye

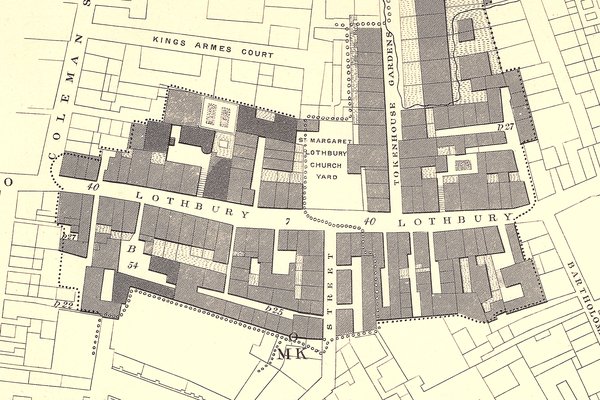

I used to walk regularly from Cannon Street tube station to the Clockmakers' Company office in Throgmorton Avenue, and on the way would walk down the west flank of the Bank of England, turn right and cross over to slip down Tokenhouse Yard. One day, passing St Margaret’s Lothbury, I stopped, and looked around. It struck me forcibly that Lothbury was really short, yet I knew that a fair number of lantern clocks were signed from addresses on the street. I was intrigued. Was this like restaurants crowding together and all benefiting from increased business?

This was back in 2018, and I conceived the idea of a deep dive into the street’s pre-Fire history. It was known for its founders, and for their ‘turning and scrating […] making a loathsome noise’. Was it such a bad place? Who else lived there, and what did they do? I recruited a research assistant, Caitlin Doherty, and together we planned trips to archives and libraries, following up hunches and leads developed together.

This all resulted in a lecture we jointly gave in November 2019, but I had to jettison more than half my material to squeeze it into a decent length. Then Covid struck and the larger work languished, until mid-2022 when I dusted it down and gave it a read. I was pleasantly reminded of much, but also conscious that a lot more could be done, so I strapped on the tanks and went overboard again.

I was still frustrated that on the first attempt I had failed to pinpoint the location of the Mermaid, the best-known Lothbury address, home to Selwood, Loomes and others, and from which the first pendulum clocks were sold in London. A punch-the-air moment occurred earlier this year when I finally found archival documents that revealed its whereabouts.

The project eventually grew to a book-length treatment and I am deeply grateful to the Society for backing its publication. It has recently been rolling through the presses. You can see pages being prepared for sewing here and the cover being embossed here.

Make no mistake, this is not a technical book about lantern clocks. But it is a forensic account of the small community in which one group of remarkable makers lived. It reveals who their neighbours were and the challenges they all faced, whether against the backdrop of the Civil Wars or the poisonous smoky atmosphere. It discusses the trades in which the merchants on the street were engaged, but reveals some of the poverty close at hand. I hope that in many ways it should throw some more light around the early life of many lantern clocks. And you can order it here!

The creation of 'A General History of Horology'

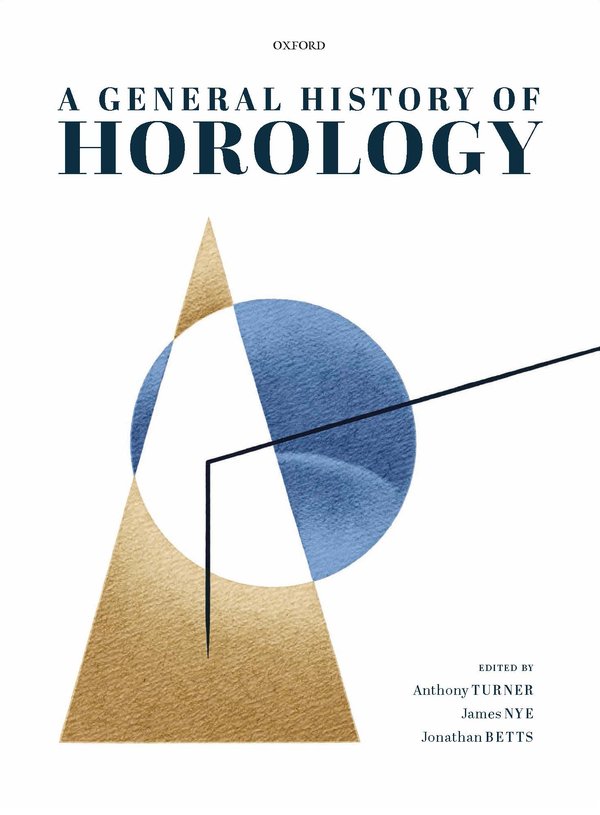

This post was written by James Nye

Winston Churchill wryly commented, ‘Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy and an amusement. Then it becomes a mistress, then it becomes a master, then it becomes a tyrant. The last phase is that just as you are about to be reconciled to your servitude, you kill the monster and fling him to the public.’

The emergence of Oxford University Press’s General History of Horology has echoed some of these observations. The editors do not necessarily agree, but I believe it was first in a bar in Pasadena, during the 2013 NAWCC conference on ‘Time for Everyone’, that Anthony Turner first broached the idea of a major work on the history of horology. I think everyone smiled politely.

Years later, in October 2016, he asked me if I would help, as his ideas were formulating and he had already managed to get Jonathan Betts interested in collaborating. However, both of us told Anthony that we were heavily committed, and I can see our emails were more than a bit tentative.

In June 2018, Anthony was back in touch, as he had now convinced OUP to get on board with the project. We met at a London hotel in July that year, and over a convivial and euphoric dinner Betts and I agreed to get fully on board as advisory editors and a firm proposal went to OUP.

August 2018 saw the beginnings of establishing the wider team of authors. The book ended up with thirty-five writers, though originally there were more.

In November 2018, OUP came back with comments from the external referees who had examined the proposal. One of them was hoist with his own petard when Anthony insisted that the referee himself fill a gap that he had indicated in the work.

A manuscript delivery deadline was set at December 2019. A draft contract emerged in January 2019, between OUP, the editors, and each contributor, eventually signed off in August 2019.

By May 2019, authors were beginning to discuss chapters with each other. It was at this point – when the euphoria had faded – that I recall joint authors were beginning to admit to each other they had bitten off what seemed like more than they could chew.

Helpfully, there were positive discussions with Sotheby’s on sponsorship. This allowed us to have colour illustrations throughout and a professionally compiled index.

Over the following months, draft chapters were beginning to fly around. Some of these were written in other languages, and needed translating to English. And more than a few were penned by Anthony himself, of course.

We had eight chapters in all by September 2019, but at this point we were also losing authors, who realised that other commitments stood in their way. And other authors were commenting, ‘Yes, I really must get down to some work!’

Unfortunately, one scholar from whom we had hoped to have a lengthy contribution died even before we could invite him. Health problems held up contributions from others.

The submission deadline shifted to late February 2020 to give us a chance to edit the whole work and to submit in turn to OUP in October that year. In January 2020 we were still scrabbling to find authors to fill a few missing parts of the jigsaw, and the timetable was under pressure. Chapters kept arriving, again some needing translation by Anthony, and some drastic editing as at least two were twice as long as required.

Eighteen chapters were in by mid-February, but as a contributing author as well as an editor, I was beginning to feel a bit of pressure myself!

The fateful month of March 2020 arrived, bringing Covid. More material arrived, but another author was lost owing to external commitments, necessitating further re-arrangement. By May we had to increase discipline significantly, since we had so many chapters on board, and three editors considering them – version control was vital.

If there had been excuses before, lockdown removed them all, and towards the end of the year the last of our contributions were coming together. It was early November 2020 that we finally had the whole book in draft, and much of that month was taken up in sorting images and securing consents.

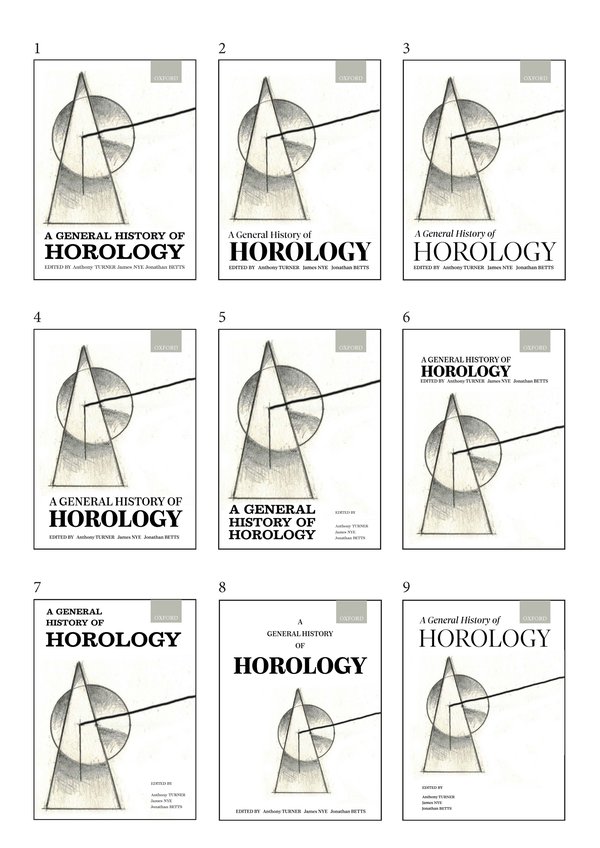

We began considering a cover in early 2021 and realised that it was necessary to look beyond accurate representations of any clocks or watches. Thus, the idea of commissioning a bespoke artwork from Lee Yuen-Rapati emerged.

In February 2021, production work on the book began in earnest. We saw first proofs at the beginning of July, and the second half of the year was taken up with gradually ensuring that myriad small corrections were made.

In early December, we realised that there were major problems with the index that had been provided, and the work had to be restarted. Tragically, Paulo Brenni, one of our authors, unexpectedly died.

We finally had a complete and workable index by mid-January 2022, with OUP sending all the files to the printers in February, while the paper actually ran through the presses on 28 March. It was then that the physical production of a slipcase managed to sabotage the timetable, and books only finally started arriving in late June.

It was quite a ride along the way. I see my computer has 27GB of material relating to the project, and at least 1,300 emails. Anthony’s statistics will be larger, given his role as General Editor.

Our aim was to offer a truly international treatment of the subject. In production it was also international. The book was written in nine countries, edited in England and France, designed and typeset in India, indexed in England and printed in Scotland.

But at least this global monster has been killed – we trust the public finds the struggle worth it.

You can order the book here. Use the promo code ASPROMP8 to save 30 per cent.

The two videos of the book being produced are courtesy of Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow.

A curious dial in a south-London cinema

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

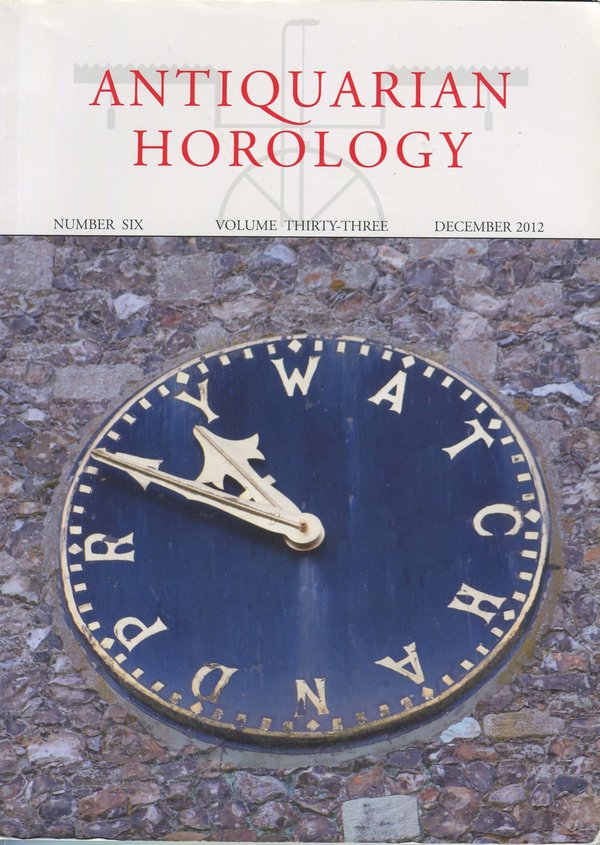

In a blog 'Letters on the Dial', posted 8 November 2012, I drew attention to dials that instead of hour numerals have letters. These can range from the name of the owner – I showed watch dials with the names Thomas Stevens, George Catling and James Catling – to a biblical quote, as seen on the dial illustrated on the cover of a journal issue.

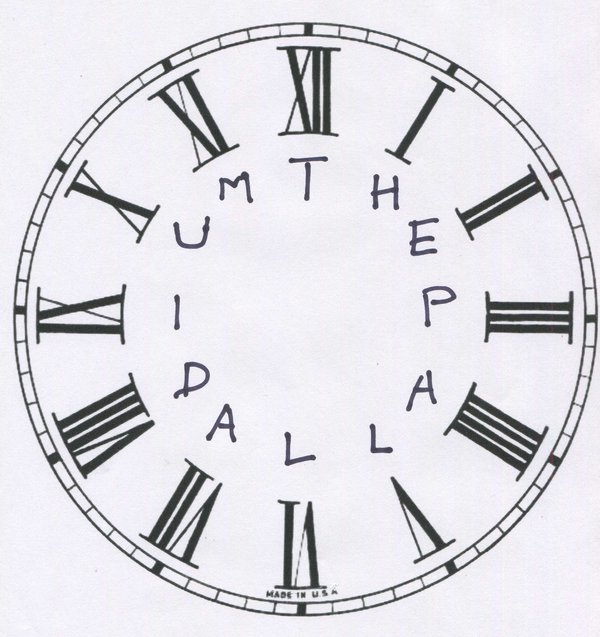

A while ago I read the first novel of the novelist and literary critic David Lodge (born 1935) called The Picturegoers, originally published in 1960. The story is set in a London suburb called ‘Brickley’, which closely resembles Brockley and New Cross in south London where Lodge grew up. It depicts the lives of a number of people of varying ages and social backgrounds who live there and go to the same local cinema, called the Palladium, on Saturday evenings.

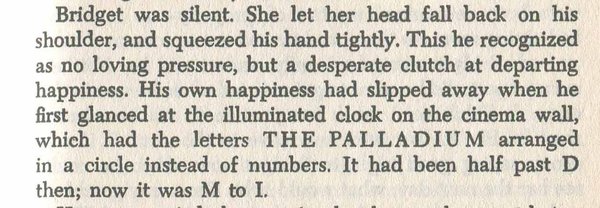

One of the characters is a young lad who takes his girl to the cinema but can hardly enjoy it as he is fretting about whether he will be on time to walk her home before his own bus, the last of the evening, leaves. 'His own happiness had slipped away when he first glanced at the illuminated clock on the cinema wall, which had the letters THE PALLADIUM arranged in a circle instead of numbers. It had been half past D then; now it was M to I'.

There was a picture theatre in Brockley named Palladium Cinema from 1915 to 1929 and New Palladium Cinema from 1936 to 1942. It was then renamed Ritz, closed in 1956 and demolished in 1960. (http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/27905). It is tempting to think that the young Lodge saw the dial there – surely he wouldn’t have made this up? I have written to the publishers of my edition of Picturegoers, Vintage, asking them to forward my question to the author, but to date have not heard back. One wonders whether others old enough to have visited the Ritz recall seeing the dial?

.

Decaying clocks

This post was written by David Rooney

I need your help!

In the final chapter of my new book, About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks, I tell the story of a plutonium timekeeper made by the Japanese electronics firms of Matsushita (now Panasonic) and Seiko in 1970 and buried in a time capsule beneath an Osaka park. It will keep time, and keep ticking, for 5,000 years.

A single gram of radioactive plutonium in the form of an oxide, wrapped in gold foil, steadily decays by alpha radiation, emitting helium nuclei into the clock’s gas chamber, which expands like an accordion’s bellows as a result. As the bellows expand, they pull the clock’s hand around the dial. You can read all about the Osaka time capsule project here.

I had never previously encountered radioactive clocks! I have spent several years studying the history of atomic clocks – the ones that use caesium, rubidium, or hydrogen – but these exploit resonance, not radioactive decay, as their time-base. So, I got interested in this new (to me) horological technology and have started digging further.

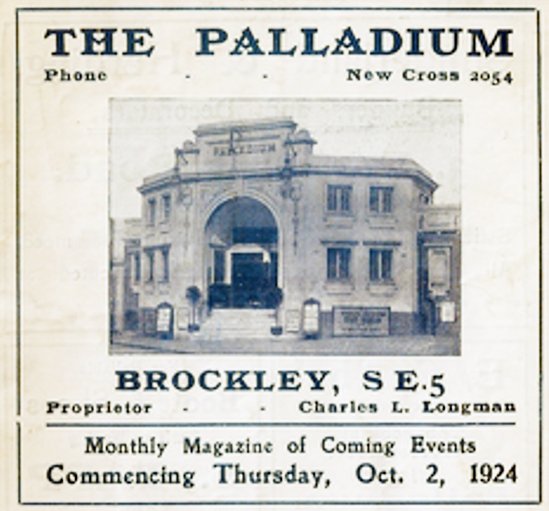

In 1959, the mayor of New York unveiled a clock at the Chase Manhattan Bank that uses gamma radiation from caesium-137 atoms to keep time. Each gamma ray detected by a Geiger tube sends a pulse of electricity to an amplifier and counter. Made by the US firm of Associated Nucleonics, it was claimed to be able to run for 200 years.

Six years later, the Benrus Watch Company filed a patent for a nuclear wristwatch using the beta radiation from technetium-99 or boron-10. In 1968, the Bulova Watch Company submitted plans for a clock that employed alpha radiation from plutonium-242, uranium-233 or neptunium-237. That one was apparently built. And in 1971, the Hamilton Watch Company’s parent body applied for a patent on an alpha-particle wristwatch using radium-226.

Here’s where I need help. Do you know of any other radioactive timekeepers, or more about the ones I’ve described here? Do you have any reference material, press cuttings, images or research reports that shed light on this novel technology? And is there a wider context I am missing – was the Chase Manhattan clock a PR exercise for the emerging civil nuclear industry, or is there a different explanation?

If you have any information about radioactive-decay clocks that you’d be happy to share with me, I’d love to hear from you. My contact details are on my website. Thanks!

'About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks' by David Rooney

This post was written by Chris Andrews

The sentence 'David Rooney has written another book' is one that should make ears prick up.

Rooney, longstanding member of this society and previously of the Science Museum and Royal Museums Greenwich, has already written one short but enjoyable and informative book about Ruth Belville, a history of mathematics to tie in with the Zaha Hadid-designed gallery in the Science Museum, and a monograph about the political history of urban traffic congestion.

His latest book may prove to be the most influential so far, and on the 16th of July over two hundred people gathered virtually on Zoom to hear David give an AHS London Lecture to tie in with its publication (AHS members can watch it here). There are innumerable books presenting the history of timekeeping and even more presenting history in general, but About Time is a rarity for considering how – in the author’s words – 'the story of time is the story of us'.

As someone who is not nearly as skilled in practical horology as some members of the society, I have gravitated towards the historical aspects of the subject. (Of course I do still, in the words of one of our founding members, 'love to watch the wheels go round'.) Those innumerable books about the history of timekeeping have given valuable insights into the innovation and development that has given us the masterpieces that tick in our hallways or on our wrists, but the subject of what those timekeepers mean to us and our lives has so often remained un-tackled.

Not so here, Rooney dives head-first into stories of how clocks have been used to enforce order, fight wars, shame the idle, make money and dream of peace.

I spent a while thinking about how best to describe the field About Time sits in – it is not strictly a history book, nor a technical work about clockmaking – and in the end, it seems like it deserves a new word. My suggestion would be that it is sociohorology, and long may this line of enquiry continue.

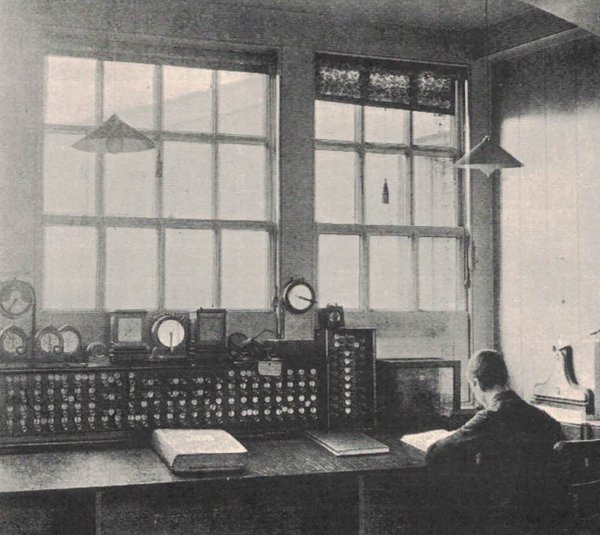

The second edition of 'Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping'

This post was written by Charles Ormrod

Robert Miles’s landmark work, Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping , sold out a few years after its original publication in 2011. Since then, copies of this highly sought-after book have been selling for several times the original cover price of £50.

The AHS is therefore delighted to announce that a long-awaited second edition is now available, made to the same standards as the first, hard-backed and thread-bound, at a new low price of just £25 plus postage.

As a humble labourer in the vineyard of the second edition, assisting James Nye with administrative work but certainly not with Synchronome expertise, I’ve had a first-class opportunity to learn about the pitfalls of editing, proof-reading, and the finer points of book production.

The possibility of a second edition was mooted some years ago, and revisions to the first edition had been contributed by Bob Miles himself, Derek Bird, Norman Heckenberg, Arthur Mitchell and others.

One of my first jobs was to combine these various sets of revisions into one document, eventually about eight A4 pages long, for presentation to the designer of the first edition, Phil Carr. Phil very generously made no charge for all the work of entering revisions into a new version of the original book’s electronic file.

Double-checking the changes and exploring disagreements between contributors led to many absorbing hours searching for clarification. I now know far more than I did about the history of sonar and the extent to which Second-World-War sonar sound-pulses fell within an audible range (which depended on whether the listener was a fit young sailor or an old sea dog).

I also learned about the Doppler effect on the sound of swinging tower-clock bells, the problems of reproducing the appearance of pre-war electrical flex, alternative cabinet-making methods applied to Synchronome cases, and the best method of setting up the suspension of a Synchronome pendulum.

I must admit I hadn’t quite realised that high-quality hard-backed books, such as the first and second editions of Synchronome, really are still made by sewing groups of double pages together with thread. A machine does the sewing of course, but the principle is broadly the same as with the earliest surviving bound books of the eighth century.

A thread-bound book is much easier to use than a glued paperback because the pages naturally fall flat when the book is opened, and thread-binding lasts far longer.

This second edition of Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping is dedicated to the memory of its author, who died earlier this year in the knowledge that work on a new edition was under way. The book is available to order on the AHS website via this link.

Dreaming of a clock in the slums of Paris

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every clock that left the workshop or factory on its way to a buyer has, we may assume, been coveted by and, we may hope, given satisfaction to its owner. But most of this goes unrecorded, and where traditional non-fiction sources are silent, we may find some glimpses in fiction.

For vivid descriptions of the life of the workers in nineteenth-century France one can do worse than turn to the wonderfully naturalistic novels of Emile Zola (1840-1902).

The book that shot him to fame in 1877 was L’Assommoir; below I quote from the most recent English translation: The Drinking Den , Penguin Classics 2000 rev. 2003, translator Robin Buss.

The novel depicts in graphic style the rise and fall of Gervaise Macquart, who worked as a laundress in Paris during the period 1850 to 1870. There are scenes of abject poverty and alcohol is a key character in the story; but there are also comical scenes and uplifting passages. It is a masterpiece. As one author has put it:

‘L’Assommoir is set in the dirt and filth of working class Paris, where life was hard and lives depressingly short. He researched in great detail the impoverished quarter of which he wrote, so that the work is an ethnographic novel and probably the first of its kind’.

In the poor household of the young Gervaise, a chest of drawers takes pride of place:

‘One of her dreams, which she did not dare mention to anyone, was to have a clock to put on it, right in the middle of the marble top – the effect would be quite splendid. Had it not been for the baby that was on the way, she might have risked buying her clock, but as it was she put if off until later, with a sigh.’ (p. 97).

Three years go by before she is able to act on her desire:

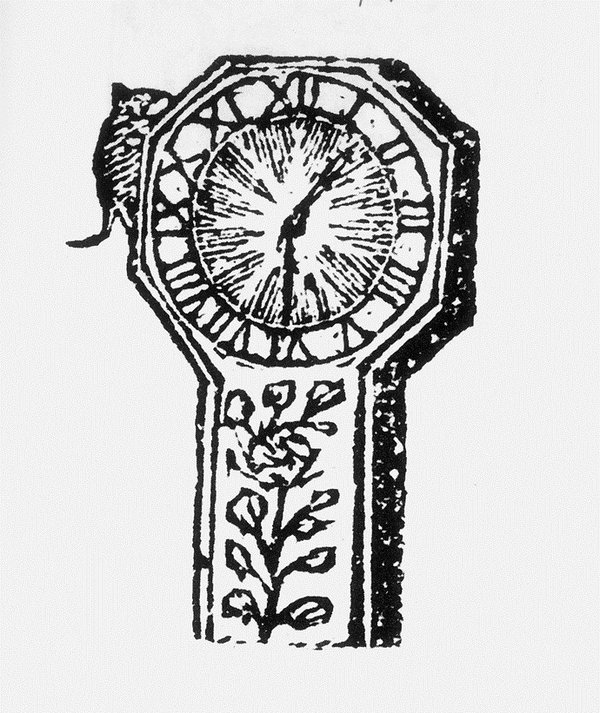

‘She had bought herself a clock; and even then this timepiece, a rosewood clock with twisted columns and a copper gilt pendulum, had to be paid off over a year, at the rate of five francs every Monday. She got cross when Coupeau [her husband] said he would wind it up, because only she was allowed to take off the glass globe and religiously wipe the columns, as though the marble top of her chest of drawers had been transformed into a chapel. Under the glass cover, behind the clock, she hid the savings book. And often, when she was dreaming about her shop, she would sit there, miles away, in front of the dial, staring at the turning hands, for all the world as if she was waiting for some particular, solemn moment before she made up her mind.’ (p. 108).

The ‘dreaming about her shop’ refers to her ambition to make herself independent and set up her own laundry, which indeed she eventually manages to do. Life looks good, she even entertains a large group to a celebratory dinner in the laundry shop.

But it was not to last, and as her life goes in a downward spiral, Gervaise is forced to bring one possession after another to the pawnbroker. She puts a brave face on it:

‘Only one thing broke her heart and that was putting her clock in pawn, to pay a twenty-franc bill when the bailiff came with a summons. Up to then, she had sworn she would starve rather than part with her clock. When Mother Coupeau [her mother in law] took it away in a little hat box, she slumped into a chair, her arms dangling, tears in her eyes, as though her whole fortune had been taken away’. (p. 279).

There is more horology in this novel. She also has a cuckoo clock, which would have been a much less valuable object, but it is never described in detail. Neither is the watch which only once makes an appearance, on the day that she is forced to put it in pawn as well:

‘The little knick-knacks had faded away, starting with the ticker, a twelve-franc watch, and the family photographs.’ (p. 384).

There is also a watchmaker who plays a small role in the story. In the courtyard of the tenement house where she lives are various workshops and shops, including – for a while – her own laundry shop:

‘At the bottom of a hole, no larger than a cupboard, between a scrap-iron merchant and a chip shop, there was a watchmaker, a decent-looking gentleman in a frock-coat, who was continually probing watches with tiny tools, at a bench where delicate things slept under glass covers while, behind him, the pendulums of two or three dozen tiny cuckoo clocks were swinging at once, in the dark squalor of the street, in time to the rhythmical hammering from the farrier’s yard’ (p. 134).

Literary critics may argue that in fiction, clocks and watches are often introduced as symbols, and that therefore novels do not necessarily give a realistic image of the ownership of clocks and watches.

Be that as it may, the story of the struggling laundress Gervaise Macquart, who dreamed of owning an ornamental clock and managed to bring one into her poor home, only to have to part with it again, feels very real indeed.

Better late than never – Baillie Bibliography Vol 2

This post was written by James Nye

Someone I know is researching the electric clock systems of Ritchie. Being a pro, I rather suspect they have run a lot of obscure sources to earth, but I’m going to make a point of drawing their attention to English Mechanic and World of Science from 1874, where I believe Ritchie published a piece on controlling clocks and time-signals by electricity.

This might come as an interesting addition to the better known 1878 piece in the Journal of the Society of Arts (vol. 26).

Another friend has a forthcoming piece on the pneumatic time distribution systems of Mayrhofer, which will appear in the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie’s next yearbook. There is just a chance he may not have come across the 1882 piece by Berly in the Journal of the Society of Arts, providing an overview of the state of the art in pneumatic horology.

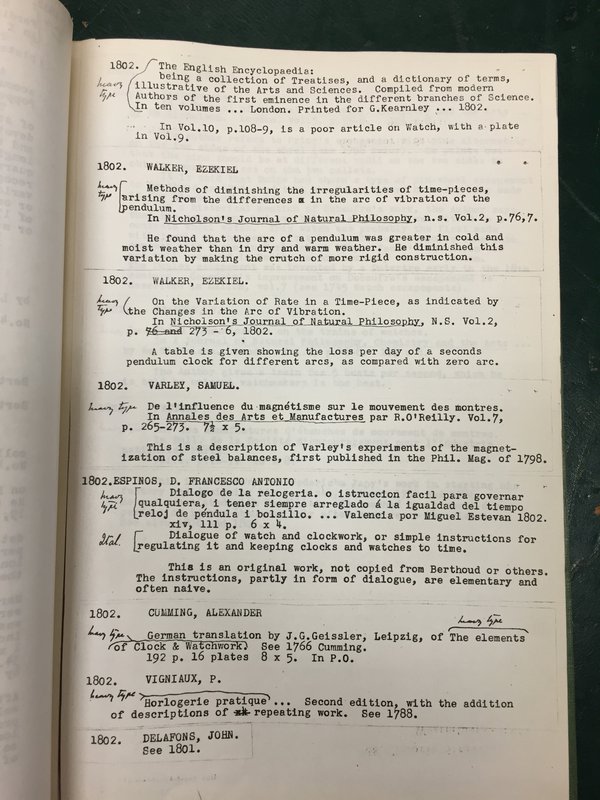

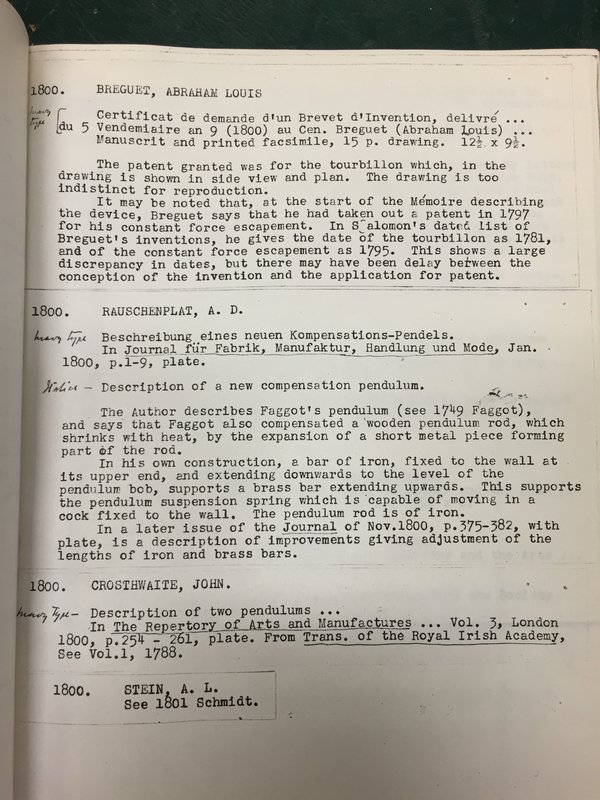

How on earth do I come to know of these possibly useful references? In 1951, G.H. Baillie published an historical bibliography, covering horological literature published prior to 1800. It has been a goldmine ever since.

A second volume, covering literature published between 1800 and 1899, was drafted, but never published – until now. The AHS has arranged the copy-typing of the typescript, and a digital (searchable) version is now available to download from the members’ area of the website.

It’s a fantastic new resource for researchers. Yes, all the obvious literature is there, of course, but there are also vast numbers of obscure references which will illuminate your research.

And Baillie included the good, the bad and the ugly.

An 1889 article on watch cocks by Luthmer is described simply – ‘the illustrations are very good. The text is of little value’. Parker-Rhodes’ 1885 pamphlet on ‘Universal Reading of Time; is ‘of no value or interest’.

But Baillie is unstinting in his praise where it is merited – witness the simple observation on Poppe’s 1801 Ausführliche Geschichte der theoretisch~praktischen Uhrmacherkunst , that ‘this is by far the best history of horology that has ever been written. Hardly a statement is made without a full reference to the authority for it.’

Membership of the AHS brings you full digital access to over sixty years of Antiquarian Horology , and other amazing digitized records – such as this latest bibliography, which finally makes an appearance sixty-five years after the author’s death. It is worth investigating.

Of mice and clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In his most recent blog, Oliver Cooke discussed watches and clocks without hands as indicators.

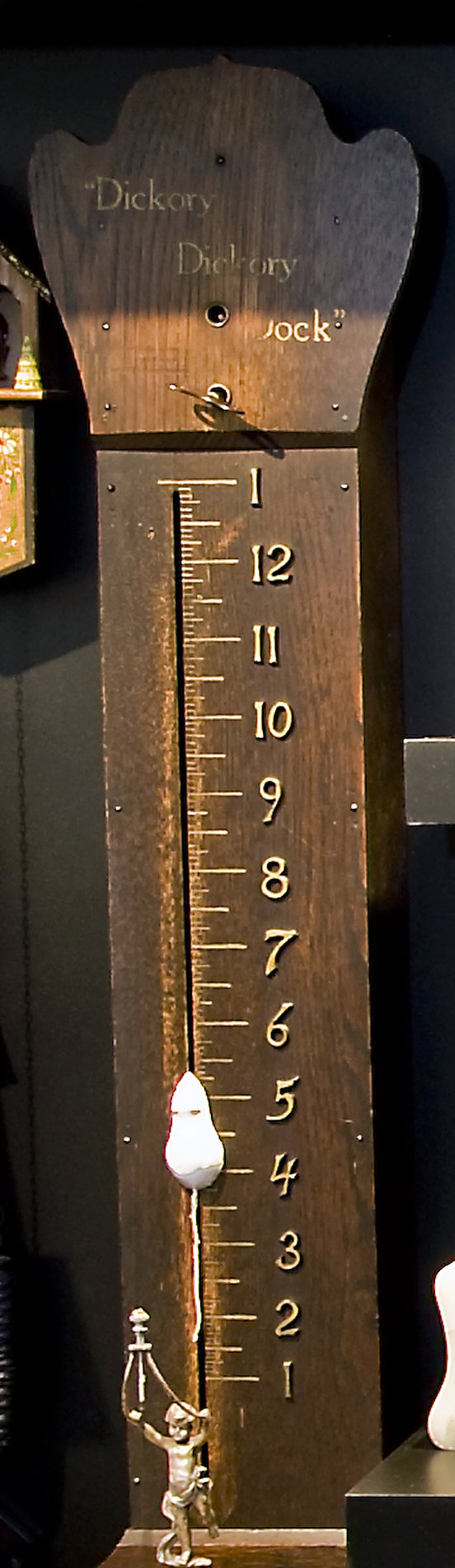

Another example is the Mouse Clock, in which a mouse making its way up against a wooden board serves as time indicator. Its designer was inspired by the well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickere, Dickere Dock

A Mouse ran up the Clock,

The Clock Struck One,

The Mouse fell down,

And Hickere Dickere Dock.

The rhyme comes in various versions; this is the oldest, published in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s_Pretty_Song_Book.

Could it be based on a real event: a mouse hiding inside a longcase clock, panicking when it struck?

In the literature I find only other explanations. One authority suggests it may be an onomatoplasm – an attempt to capture, in words, a sound; in this case, the sound of a ticking clock. Another relates it to the shepherds of Westmorland who once used ‘Hevera’ for ‘eight’, ‘Devera’ for ‘nine’ and ‘Dick’ for ‘ten’ when counting their flock.

Be that as it may, just over a century ago it inspired an American businessman, who was also an avid clock collector, named Elmer Ellsworth Dungan, to develop the Mouse Clock.

He initially just created one for his daughter, who loved the nursery rhyme, but then decided to take them into production. He took out patents and various models were manufactured.

They are nowadays prized by novelty clock collectors, so much so that we are warned to beware of reproductions, especially for what one dealer calls ‘Chinese knockoffs’.

Details, including several images of the mechanism, and a link to an animated photo of the clock in operation, can be found on these American websites: Antique Clock Guy and Fontaine’s Auction Gallery.

In 1966 the NAWCC published a booklet by Charles Terwilliger, Elmer Ellsworth Dungan and the Dickory, Dickory Dock Clock; there is a copy in the AHS Library at the Guildhall.

And speaking of mice and clocks, how about having some fun with the (grand)children with this on-line clock reading game. Read the time correctly and the mouse runs up safely to the cheese in the clock. Read it wrong and the cat gets the mouse.

Stopping the clock after death

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In a previous post I included an opera scene, in which a woman mentions (sings!) that at times she stops all the clocks in her house. She dreads getting old and wants time to stand still.

One reader told me this reminded him of a poem by W.A. Auden which begins:

'Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

'Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

'Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

'Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.'

But here the motive for stopping the clocks is different. Someone has died, and stopping the clocks in the house of the deceased, silencing them, is an old tradition, similar to closing the blinds or curtains and covering the mirrors. The clock would be set going again after the funeral.

Some people believe stopping the clock was to mark the exact time the loved one had died. The subject was discussed here by members of the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in America.

The French film Jean de Florette, set in the Provence between the wars, contains such a clock-stopping scene. The film is made after a novel by Marcel Pagnol, from which the following quotes are taken.

Jean, an outsider, inherits a house with surrounding land and hopes to make a living there. But two locals, who covet his land, secretly block a source, cutting off his vital water supply.

In despair, Jean uses dynamite to create a well, but he dies as a result of the explosion (chapter 37). The doctor, taking his pulse, 'listened for a long time in a profound silence emphasized by the ticking of the grandfather clock', but the man had died.

Then one of the two devious locals, who was in the room, 'crossed himself, walked around the funeral table on tiptoe, and stopped the pendulum of the grandfather clock with the tip of his finger'.

He then tells his comrade in arms 'Papet, I have just stopped the grandfather clock in Monsieur Jean’s house' – a way of saying: he is dead.

The three stills reproduced here are from that scene, which you can see in this short clip.

The clock is a typical Comtoise grandfather clock with a big flower pendulum.

An experiment in ‘florology’

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

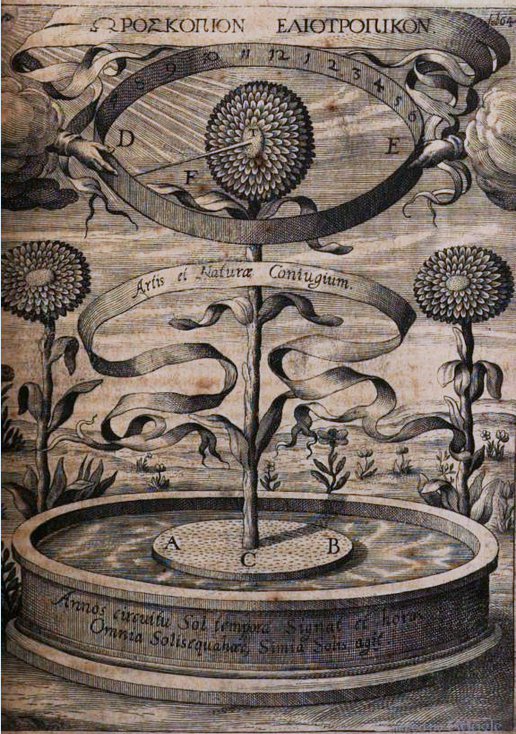

Recently, I have been looking at the role of timekeepers in the history of science and whilst reading around the pre-pendulum era, happened upon a blog-worthy experiment conducted by Athanasius Kircher (1601/2-80).

Kircher, a German Jesuit polymath, applied the then known phenomenon of heliotropism as a method of timekeeping.

He thought that the daily motion of sunflowers as they followed the Sun was caused by magnetic influence and thus inferred that they could be usefully used as a clock. As can be seen in his magnificent illustration, Kircher planted the sunflower in a cork pot and floated it on water, providing a frictionless pivot, and inserted a pointer through the flower to indicate time against the annular chapter.

Kircher noted that his clock was disturbed by the slightest of breezes and, when kept away from sunlight, it withered and its motion slowed. This, however, did not end the experiment. He tells us that he had the good fortune of meeting an Arab trader who happened to have amongst his aromatic wares a substance with similar horological properties to the sunflower.

The deal was struck and Kircher parted with his sundial signet ring for the horological stuff.

It has to be said that this episode is possibly a theatrical device to colour the account and introduce the use of sunflower seeds and root instead of the plant itself, but worth repeating – even if it’s just an excuse to show a beautiful horizontal sundial ring!

Today, we know that this diurnal motion is caused by sunlight and so Kircher’s clock could never have worked in the way intended, but one cannot help admire his ingenuity in applying a mystery of the physical world to tell the time. M. Becker’s 2011 time lapse movie shows that it is possible to use a flower as a twenty-four hour clock, but only in summertime at a latitude close to the north or south pole.

300 years

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

This year saw the tercentenary of the death Thomas Tompion (b.1639), the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’ and his life is celebrated in two special exhibitions: the first at the British Museum, entitled ‘Perfect Timing’, which focuses on the magnificent Mostyn Tompion and the second, ‘Majestic Time’, at the National Watch and Clock Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Tompion enthusiasts should be further delighted by the announcement of the forthcoming publication of ‘Thomas Tompion, 300 years’. The book promises a wealth of new detail, fresh illustrations and includes Jeremy Evans’s previously unpublished chronology of Tompion’s life.

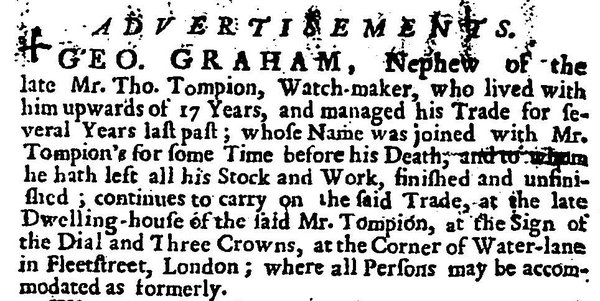

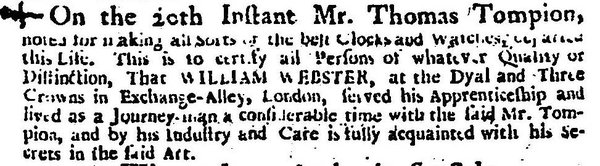

This tercentenary marks not only an end, but a new beginning as Tompion’s nephew by marriage and then business partner, George Graham (c.1673-1751), inherited and continued the business at the corner of Water Lane. As far as I am aware, the earliest announcement of Graham’s succession was first advertised in The Englishman one week after the death .

William Webster, however, did not show the same reserve. He had an advert published the day after Tompion’s death in two papers: The Mercator or Commerce Retrieved and The Englishman. His announcement of the death was a thinly veiled attempt to attract business and was repeated in various papers that week.

Unlike Webster, Graham was not apprenticed to Tompion (several publications incorrectly cite Graham as being so). He joined the household sometime around 1676 after gaining his freedom from apprenticeship to Henry Aske.

Evidence suggests that Graham did not serve his entire apprenticeship under Aske and it is currently a mystery as to where he was during the last years of his apprenticeship.

Looking forward to next year there is another important tercentenary, that of the Queen Anne Longitude Act. George Graham played an important role as an encourager and advisor to both Henry Sully and John Harrison in their efforts to produce sea-going clocks and will feature in a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum next year.

Seventy-Seven Clocks

This post was written by David Rooney

One of the security officers where I work stopped me a few weeks ago. He was reading a crime fiction novel and thought I might be interested. It’s called ‘Seventy-Seven Clocks’. You can perhaps see why he thought of me.

During these long January evenings, many of us find time to catch up on our reading – and there’s a lot to catch up on.

I am sure you are already onto your second reading of Bob Miles’s superb masterwork on the Synchronome company, published by the AHS last year. And if you haven’t yet seen a copy of Ian White’s exploration of English clocks for the Eastern markets, the AHS’s latest book, then there’s a treat in store for you.

But having devoured those two books, you might want something a little lighter, and for that, I can recommend Christopher Fowler’s Seventy-Seven Clocks.

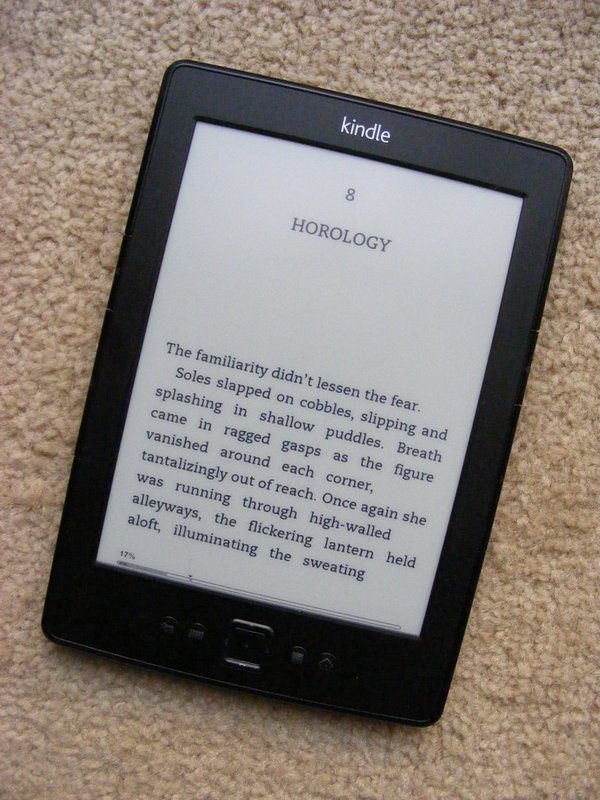

With chapter titles such as ‘Horology’, ‘Clockwork’, ‘Automaton’ and ‘Mechanism’, it’s shot through with mechanical ingenuity. (There’s also ‘Vandalism’, ‘Detonation’, ‘Darkness Descending’ and ‘Glorious Sacrifice’, so it’s not for the faint-hearted.)

I don’t want to spoil the plot, but suffice to say anyone who’s a member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, or who collects clocks and watches, or who has ever been involved in running a business might well be absorbed by Fowler’s fictional tale.

It’s beautifully detailed, acutely observed, and full of horology – although I never imagined it could be so wicked ! I’ve since read other titles in Fowler’s series and they’re great. One mentioned the sundial-fountain in St Pancras Gardens by horological philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts that I wrote about a few months ago. Coincidence!

Happy reading, whatever’s on your bedside table, and very best wishes to you all for 2013.

The Silver Swan fictionalized

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The latest novel by the Australian author Peter Carey, The Chemistry of Tears, was inspired by the Silver Swan of Bowes project.

The Swan is an amazing late 18th-century, life-sized automaton, incorporating three clockwork mechanisms or movements, products of the clockmaking trade. It has been in the Bowes Museum in County Durham, Northeast England, since 1872 where it can be seen in action every afternoon.

In 2008, the Swan underwent a major conservation project, undertaken by our Council member Matthew Read. In 2010 he gave a fascinating talk on the subject for our Society, and recently he went back to Bowes to see that all was well, as reported in his blog ‘Friends Reunited’.

The story in the novel goes back and forth between the 19th century and the present. An Englishman commissions an automaton to be made in Germany. It’s inspired on Vaucanson’s famous digesting duck automaton, but somehow turns out as a (the?) swan – it’s all a bit unclear.

In modern London, a conservator in a fictional museum is given the task of restoring the by now dismantled automaton to working order. Her manager has set her this challenge, hoping it will take her mind off her grief over her lover’s sudden death.

Does it work as a piece of fiction? I am not sure. But what I am sure of is that there cannot be many novels that explicitly mention our journal:

'It was then, high on grief and rage, I stole two of Henry Brandling’s exercise books. What would happen if I was caught? Burn me alive, I didn’t care. I tucked them inside my copy of Antiquarian Horology, and walked straight past Security and out into the London street which was now, in late April, hotter than Bangkok' (p. 34).

If anyone knows another novel in which our journal occurs, please leave a comment!

A la recherche du temps synchronisée

This post was written by James Nye

A number of us are fascinated by the whole concept and practice of synchronized public time. As well looking at the time transmission systems installed in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin and elsewhere in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, there are other intriguing facets to the world of time, its accuracy and its perception.

On something of an exotic riff, consider time in art. Dalí played with relativity in The Persistence of Memory and its softening watches, whilst Proust’s masterwork meticulously articulates the recovery through memory of a life observed at obsessively close detail – one can feel the clock ticking the author’s life away second by second as the narrative unfolds.

Back to the main hook, and significantly more prosaic, the clock, or broken watch, features regularly in detective fiction – think of Agatha Christie’s Clocks . Alibis often depend on time. I’ve collected detective fiction all my life, and recall the pleasure at finding Lord Peter Wimsey occupied a world full of synchronized clocks.

Witness the following from one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ finest books, Murder Must Advertise:

'The tea-party dwindled to its hour’s end, when Mr Pym, glancing at the Greenwich- controlled electric clock-face on the wall, bustled to the door, casting vague smiles at all and sundry as he went.'

Later in the same book, we learn of Wimsey’s difficulties at remaining in character, in disguise in an advertising agency… 'Nor, when the Greenwich-driven clocks had jerked on to half-past five, had he any world of reality to which to return…'

Sayers again touched on a number of public time themes in a later Wimsey story, Have His Carcase:

'In that intriguing mystery, the villain was at that moment committing a crime in Edinburgh, while constructing an ingenious alibi involving a steam-yacht, a wireless signal , five clocks and the change from summer to winter time.'

I’ll close with an appeal. If you know of similar appearances of time-signals, synchronized clocks and the like, in plays, novels, whatever, I’d love to hear about them!

A multiplicity of times

This post was written by David Rooney

David Thompson’s post about Metamec ‘time savings’ clocks excited me, because I am interested in the wider cultural meanings around seemingly innocuous phrases such as ‘time is money’.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on the subject for the Science Museum’s ‘Ingenious’ website. It looked at the history of Benjamin Franklin’s 1748 phrase and how its meanings in different times and places varied.

Reading the article back, I have been reminded of a fascinating book by anthropologist Kevin Birth called Any Time is Trinidad Time (University Press of Florida, 1999).

Here’s what I wrote for the Science Museum:

'Trinidad, a Caribbean island between Venezuela and the USA, has a rich history of settlement and immigration. It is ethnically and culturally highly diverse, with residents of mainly Black and Indian origin mixing with Spanish, French and English colonial culture.

'Social anthropologist Kevin Birth spent time living there in 1989 in order to study cultures of timekeeping. Starting out with the often-used phrase "any time is Trinidad time", originally attributed to calypso singer Lord Kitchener, Birth explored the ways people come together with differing notions of timekeeping, and how conflicts are managed.

'He also looked at phrases like "time is money", "time management" and "budgeting time" and found that their use and meaning is highly complex and culture-specific. Generalisations were impossible.

'We all carry around with us a great variety of "personal times" – value systems linking time with activity – and we deploy them in highly complex ways according to culture, context and circumstances. Phrases like the Lord Kitchener lyric are complex devices used to oil the wheels of societies under time pressure.'

If you’re interested in how different societies use clocks, I can heartily recommend reading Birth’s book.

A book sale to remember

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Many of us who are captivated by the history of timekeeping have an equal interest in the historical literature on the subject; in fact, such is the fascination with antiquarian horology, that quite a few of us have more books than clocks and watches!

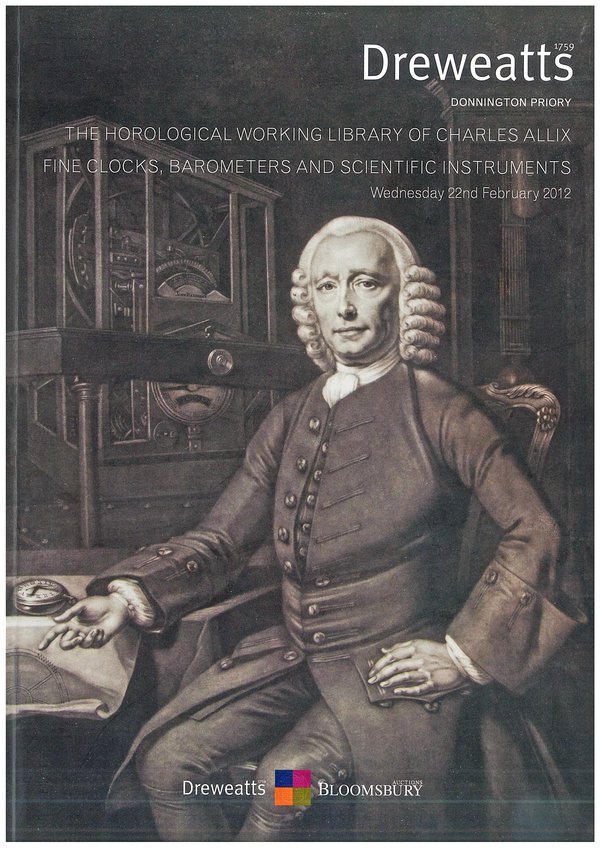

For these horological bibliophiles (don’t try saying that with your mouth full!), ‘the sale of the century’ took place last month (on 22nd February) when Dreweatts of Donnington sold the working library of the distinguished antiquarian horologist, Charles Allix.

Charles, who is now enjoying a well-earned retirement, amassed a very fine collection of books and ephemera, and with subjects ranging from turret clocks to watches, there was something for everyone.

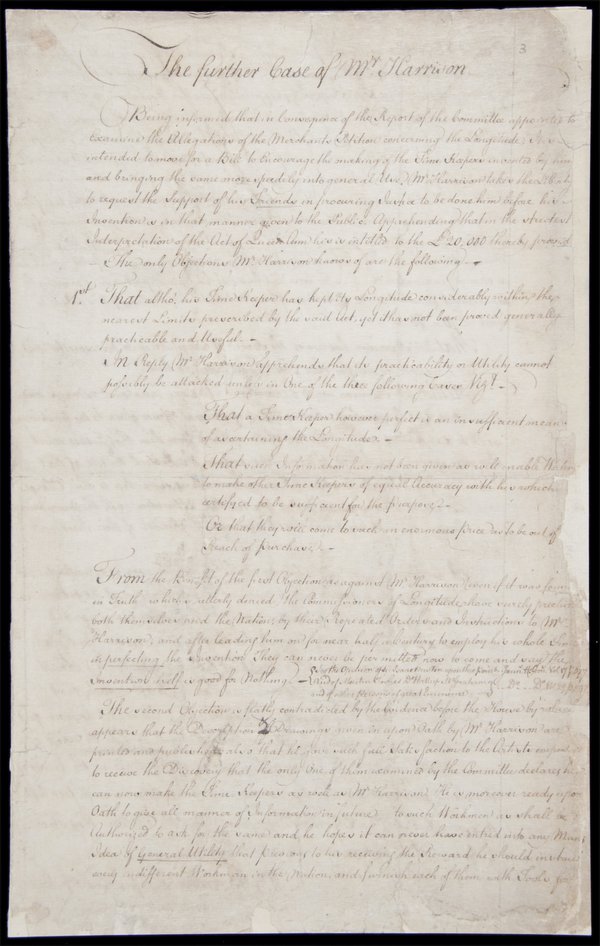

Undoubtedly the stars of the show were a small group of manuscripts which had belonged to the great John Harrison (1693-1776) and it was predictably these lots which brought the highest bids.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers hold the largest body of original Harrison manuscript material, and the Company were keen to add these, which were some of the very last Harrison-related documents out of safe captivity in museum collections.

The lots were hotly contested – some of the prices were a long way above upper estimates – and the horological world was reminded again of the enduring interest and importance of the Harrison story.

In the event, most were acquired by the Company (Charles Frodsham’s kindly doing the bidding on their behalf), and they are now safely secured for the future and available for research.

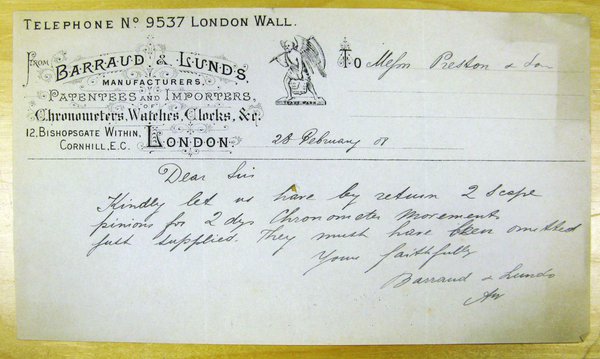

My own organisation, recently re-named Royal Museums Greenwich (after the Borough was granted Royal status) was also successful in acquiring some fascinating correspondence from the firm of Preston’s of Prescot, one of the most significant English manufacturers of rough movements for marine chronometers.

The extraordinary detail informing the day-to-day processes involved in making and supplying these movements to the finishing trade, will greatly enhance the research currently being carried out on the museum’s collection of marine chronometers.

This research is due to be published in a large and definitive catalogue The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich , due out in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the 300th anniversary of the famous Act of Parliament offering huge prizes for solutions to the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Horological research

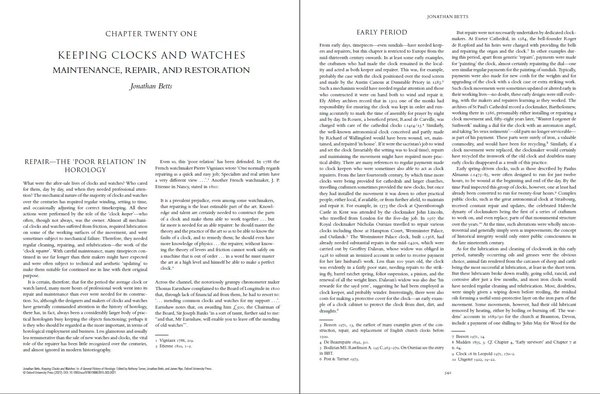

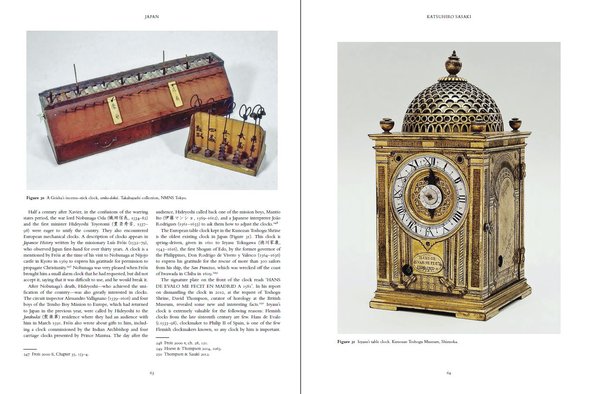

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Determined to ‘practice what we preach’, a number of us on the Council are currently involved in our own horological research; my project at the Royal Observatory Greenwich is the study of our enormous collection of marine chronometers.

The research will lead to the publication of a catalogue raisonne, ‘The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich’ in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the tercentenary of the passing of the great Longitude Act in 1714, and will form one of the series of Greenwich instruments catalogues published in recent years in conjunction with Oxford University Press.

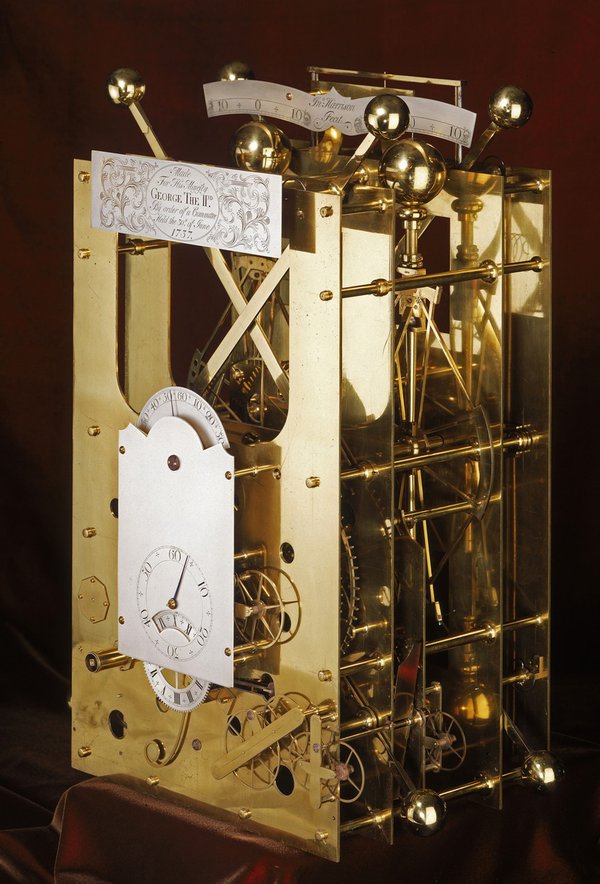

All the timekeepers by the great John Harrison have now been fully dismantled, studied, photographed and researched (and put back together!) and I am now slowly working my way through the rest of the collection, from early examples by John Arnold up to the 4 orbit Hamilton, the rare Model 21 marine chronometer adapted to aid pacific navigation.

One of the great challenges for the catalogue is to write a ‘spotters guide’ to help collectors, dealers and curators with the tricky question of ‘how to date and evaluate your marine chronometer’. In the early years there were obvious differences in evolution and from one maker to the next, but, from the 1840s, marine chronometers appear, at first glance, to change very little through into the 20th century.

There are however many things to look out for, both in the movement and the box, which will enable a more sophisticated evaluation of a given chronometer. But be warned! These functional objects have often had considerable alteration and ‘upgrades’ over the years (lives depended on their being ‘up to date’, after all) and we should be prepared to accept, and dare one say rejoice in, instruments with a complex history. Later posts may expand on this interesting aspect.