The AHS Blog

Wristwatch Group meeting, 14th January: conservation and restoration

This post was written by Mat Craddock

In the gas-fired warmth of the Royal Arcade, WWG members heard Justin Koullapis (our gracious host, The Watch Club), Adam Phillips (casemaker and restorer), Greg Dowling (WWG member and watch collector) and Oliver Cooke (Curator, Horological Collections at the British Museum) discuss originality in watches.

Oli’s curatorial view of conservation was, perhaps, the most extreme: once an item enters a collection, the aim is to put it into stasis, free from the damaging effects of winding or lubrication.

From a collector’s point of view, Greg said that the possibility of wearing and using a watch might lead him to seek out to the most appropriate way to restore the piece to working order.

Adam agreed, and seemed largely happy to undertake work under the direction of his customers, taking the view that sensitive restoration and repair can extend the useful life of a watch.

Justin’s thoughts on the subject were from two, contrasting, points of view: as a non-practising watchmaker and as a watch dealer. He said that great value is placed on entirely original objects, many of which have been hidden away for many year. However, his fascination with how objects were made often caused him to place more value on the skills of the watchmaker, rather than the watch itself.

Questions were taken from the audience, and covered topics such as dealer versus collector (the panel was split on the definition of a collection); the dangers of old radium (the British Museum has their luminous watches stored in steel-lined rooms that are externally force vented); and even the purpose of collecting watches.

In response to the last question, Mr Dowling quoted from the late Dr George Daniels: there’s nothing more attractive than a good watch. It’s historic, intellectual, technical, aesthetic, amusing, useful.

A fitting end to an interesting evening.

The annual winding of the Mostyn Tompion

This post was written by James Nye

28 January 2016. To the British Museum, at the delightful invitation of the horology curators to take part in a little-known and wonderful ceremony – the just-once-a-year winding of the glorious Mostyn Tompion.

The Deputy Director, Jonathan Williams, offered a warm welcome, amply elaborated by Paul Buck, senior horological curator, who walked us around the origins and detail of this extraordinary object.

It runs for a whole year on one wind, striking every hour of that year (56,940 blows). The clock case, a confection of ebony veneer, silver and gilded brass, is rich in symbolism, covered in the heraldry and armorial paraphernalia of England and Scotland, richly intertwined – an interesting hint to the politicians who only wind each other up on such matters.

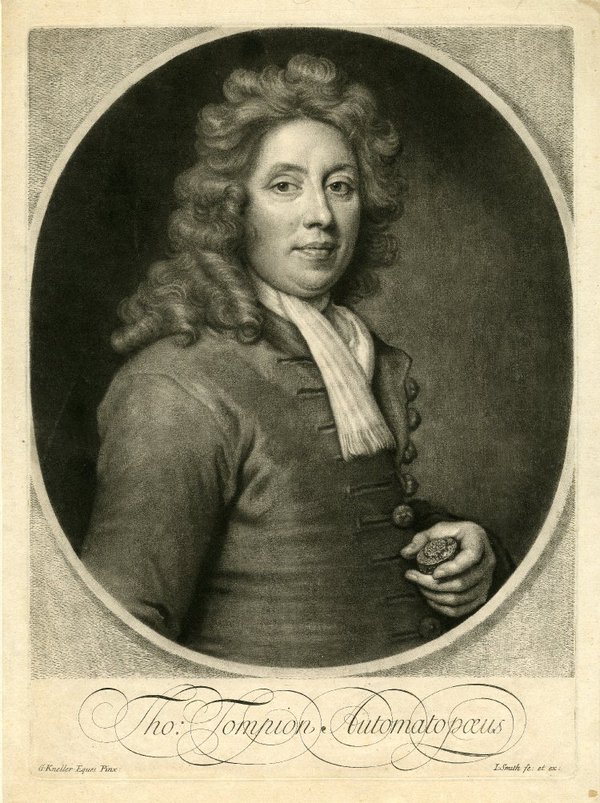

Made for King William III by perhaps our most celebrated maker – Thomas Tompion ( Westminster Abbey-buried, no less) – the clock descended on the royal death through various titled families before settling with the family of the early Lords Mostyn, finally landing in Great Russell Street in 1982.

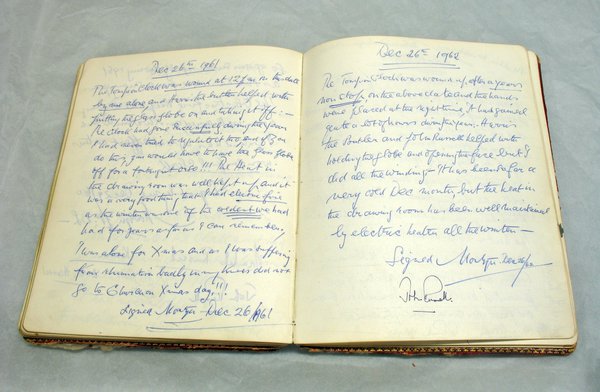

From c.1793, the Lords Mostyn held a small party to mark the annual winding of the clock, with each winder entering their name in a book. This tradition has been kept firmly alive at the British Museum.

The old family record was open for us to see, turned to the page for 26 December 1961, when Lord Mostyn recorded being on his own for Christmas, and winding the clock, which had ‘gone successfully during the year’.

Amusingly his idea of being on his own did not allow for the presence of the butler, who helped replace the dome over the clock.

These were memorable times – Mostyn, much troubled by rheumatism, also recorded ‘The heat in the drawing room was well kept up, and it was a very good thing that I had electric fire as the winter was of the coldest we had had for years’.

Winter, spring, summer and fall continue to unfold, watched over from Gallery 39 by a remarkable clock, which draws breath just once in each cycle of seasons.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ Time Machine: perpetual calendar or not?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

I am fascinated by gimmicks used by past watch manufacturers to make their products stand out in a crowded marketplace and this post is the first in a short series on some attention seeking watches that have piqued my interest.

This post takes a look the Wittnauer ‘2000’, a quirky automatic wrist watch from the 1970s.

It is a snazzy-looking chunk of a watch and is impressively big at 46mm across the case and crown; the dial does not disappoint with its day, date and complex-looking calendar information around two apertures at twelve and six o’clock.

It was advertised in the early 1970s as a time machine with perpetual calendar, which is technically correct but arguably a little misleading.

The perpetual calendar is a celebrated complication prized by collectors of high-end wrist and pocket watches.

The intricate mechanism required to keep the calendar in step with the short months and leap years demands multiple precisely made components, is only found on the best watches and, unsurprisingly, its presence in a watch hikes the value substantially.

Stephen McDonnell’s recent innovative perpetual calendar design. Uploaded to Youtube by Quill and Pad.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ has a perpetual calendar, which does conform to the same definition.

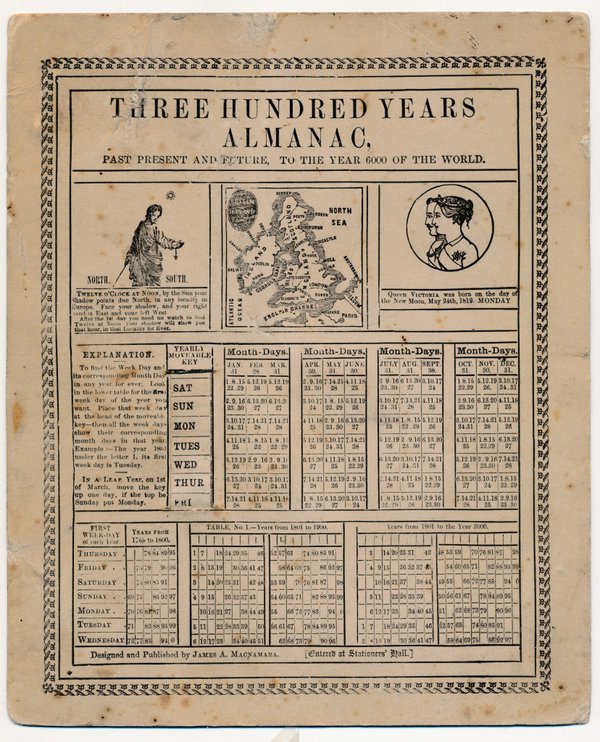

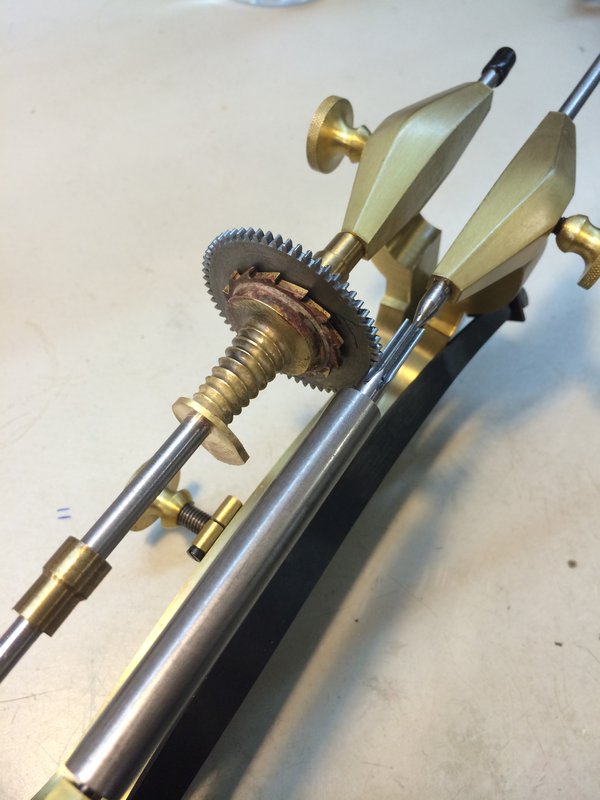

The date display is a standard type, which must be manually advanced at the end of a short month. It is more normal for the calendar to be set using the crown, but why do that when you can have an extra button on the outside of the case? Instead of keeping the date in sync, it uses tables and a revolving scale to reckon the day of the week for a given date.

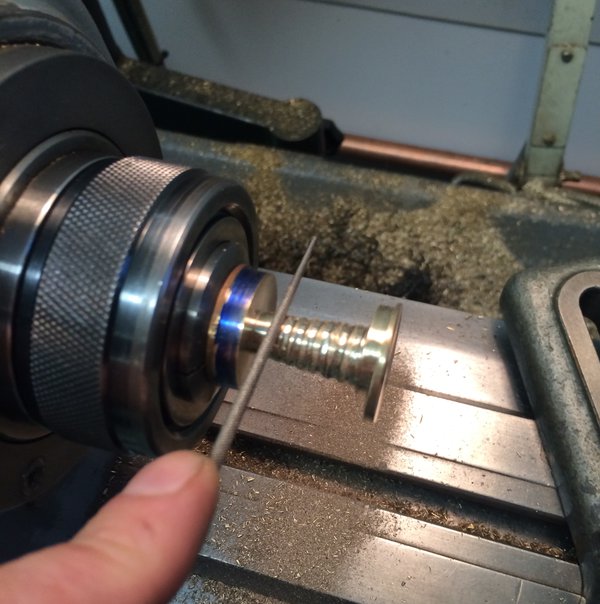

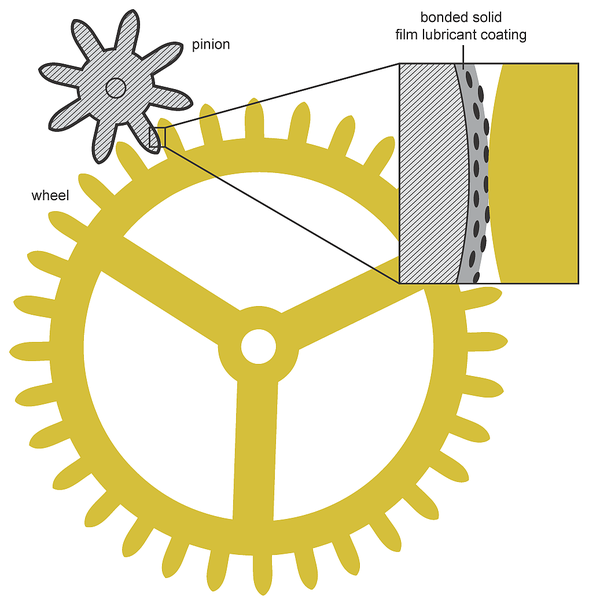

The mechanics of the design are very simple, the revolving disc has a contrate gear on its reverse, which is driven by a pinion attached to a second crown.

The years and days of the week are printed on the revolving disc and, as can be seen in the image, aligning the year with the month on the lower table (at six o’clock), places each day of the week above one of seven columns (at twelve o’clock) that contain the relevant days of the month.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ perpetual calendar employed an old and simple technology to allude to luxury. For a modest price it had bags of 70s style and, as with any self-respecting time machine, had buttons aplenty!

Winding the Caledonian Park turret clock

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

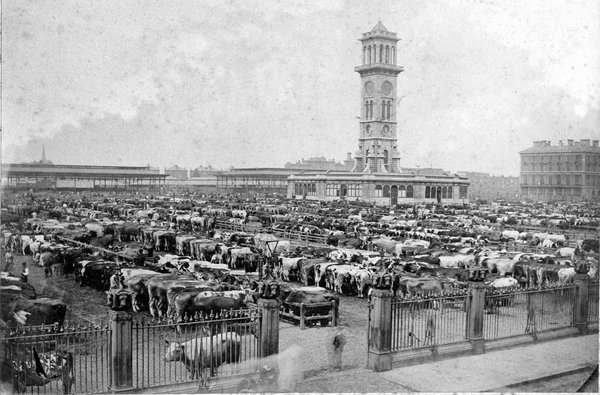

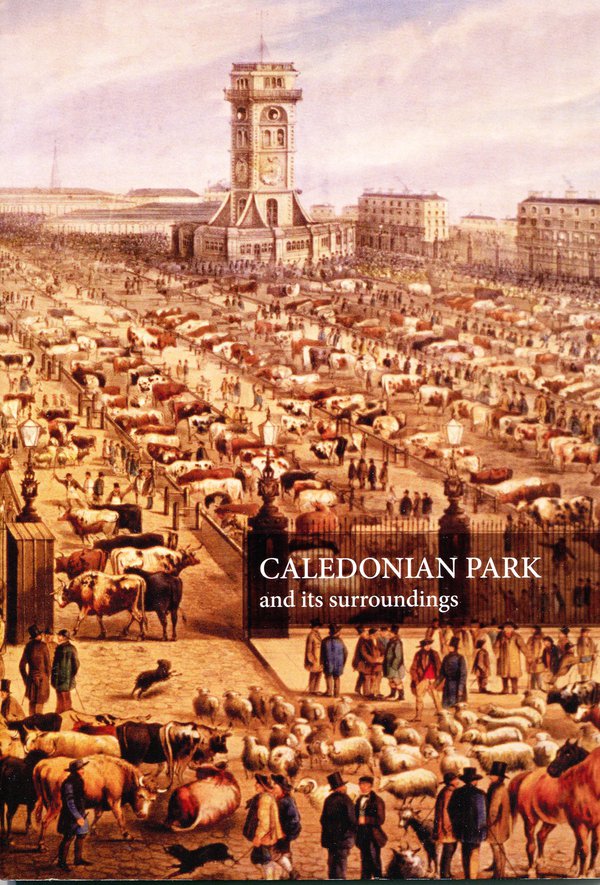

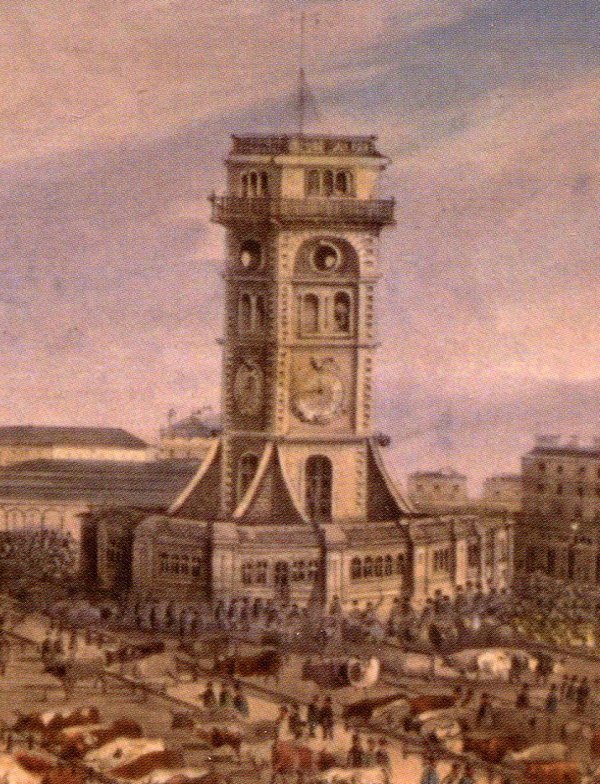

In Caledonian Park, in the London Borough of Islington, stands a distinctive 45 meter clock tower with four dials that can be seen from far away.

It was erected in the 1850s to serve as the command centre of the newly laid out Metropolitan Cattle Market, which had been created to replace the old more centrally located Smithfield Market. The tower is a Grade II listed building.

You can see the clock movement in this short videoclip:

Turret clock expert Chris McKay has recently published a facsimile reproduction of A List of Church, Turret and Musical Clocks. Manufactured by John Moore & Sons. 38 & 39, Clerkenwell Close, London, dated 1877.

For the year 1854 we find: ‘Islington, London Four 10-ft. 6-in. dials, chiming, for the Cattle Market.’

The chimes are no longer in operation, from what I understand at the insistence of nearby residents. But the clock is still running and showing the correct time.

During an open day last summer I had a chance to get into the tower, and to see the clock and enjoy the view from the balcony.

The organizers were looking to extend their group of volunteers for the weekly winding of the clock. I signed up and am on the rota now, so I regularly climb first a cast iron spiral staircase and then a series of steep ladders to get to the movement and pull up the heavy weight.

It’s a good physical exercise and a welcome hands-on experience for someone whose involvement with horology is normally limited to sitting at a desk putting together the quarterly journal of the AHS.

The Caledonian Park Friends Group have published a booklet with much information on the history of the market, which for a while also functioned as a flea market.

The cover shows the market in full swing, but the artist has made a bad job of representing the tower. If the dials were really as low as where he painted them, climbing up to wind the clock would be a lot easier!

Donation to the British Museum

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

I write with a foot in two allied camps: as a member of the AHS and a Curator of Horology at the British Museum.

In October last year the AHS Council generously donated sixteen interesting clocks, watches and horological tools to the BM collections. The items had in fact been at the BM since 1973, having been deposited on long-term loan when the AHS left its former London HQ.

This conversion to a donation consolidates that loan and upholds one of the core objectives of the AHS which is the support of public collections.

Let us look at three of the items.

Firstly, a lantern clock with centre verge pendulum by Johannes Kent of Congleton, Cheshire, late 17th century.

Lantern clocks with centre pendulum sometimes had 'angel wing' extensions to the side doors to accommodate the arc of pendulum. This clock does not have these, but the side doors (which seem to be later) do not interfere with the action of the pendulum.

Unusually for this time, the clock does not have Huygens’s endless winding system, but has a separate drive for each train.

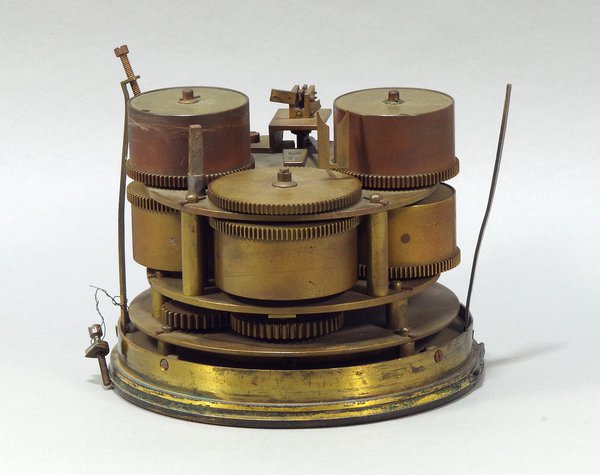

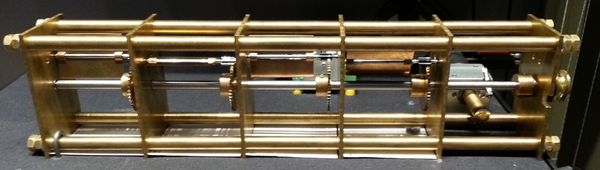

Next, an interesting year-going movement. This was probably housed in a slate or marble case, perhaps something like this.

The inscription on the dial is somewhat rubbed and not wholly legible, but it seems to be signed for Edward Watson of King Street, Cheapside, London (working 1815-63) who would have been the retailer for the clock.

The movement is stamped to show that it was made by Achille Brocot of Paris. Brocot invented this type of long duration movement in the mid-19th century, employing multiple mainsprings in going barrels to drive the clock.

The system has great advantages over using a single large mainspring to achieve a long duration. Smaller springs are easier to make and much easier to remove for maintenance. Also, if one of the five springs were to break it would cause far less damage to the clock than a recently-wound single spring with a year’s worth of driving energy being unleashed.

… and finally, an unusual and incredibly useful screwdriver. It has five slot heads at different orientations enabling access to those awkward screws, such as between the plates of a movement.

Right, I’m off to attend to a newly-installed longcase clock which has stopped – an in-situ adjustment of the back cock should do it..!

As with all items in the collections of the British Museum, these items are kept to be made accessible to all members of the public. An appointment to study them can be made by contacting the horological team at horological@britishmuseum.org or by telephone (020 7323 8395).

How did Arnold get to the Clockmakers’ Museum?

This post was written by David Rooney

On 23 October, the Clockmakers’ Museum opened at the Science Museum. The new gallery is a treasure-trove of horological history, home to so many wonderful items it’s hard to know where to look next.

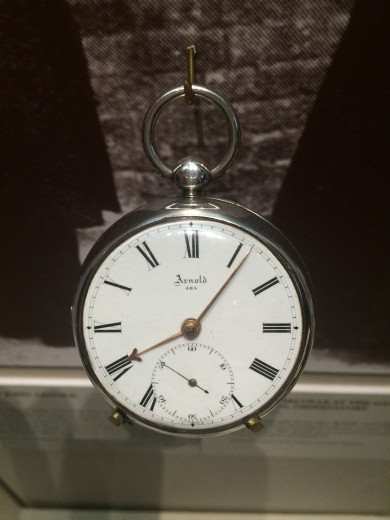

Tucked away in one showcase is a modest-looking pocket watch that would be easy to miss, yet tells a story close to my heart—that of Ruth Belville, whose biography I wrote in 2008.

The watch was originally the property of John Belville, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, who used it between 1836 and his death twenty years later to carry accurate Greenwich Time round a network of subscribers across London.

When John died in 1856, the watch was passed to Maria, his wife, who continued carrying it round London until 1892, when she retired.

She then passed it to her daughter, Ruth, who named it ‘Arnold’ after its maker, John Arnold. Ruth carried the time to town with Arnold until 1940, when she retired, aged 86.

But it was not the end of the line for Arnold. Ruth had always wanted it to have a good home.

‘When it retires from business … I think the dear old thing ought to be put in the British Museum’, she told the Evening News in 1908. In 1921, Ruth changed her mind, stating that she ‘should wish the Royal Observatory to have the first offer of purchasing my chronometer’.

Yet neither received Arnold.

In 1941, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers granted Ruth a pension which gave her crucial financial security in her retirement.

Ruth repaid its generosity in January 1943, when she wrote to the Company offering her watch for its museum when the time came. The Company accepted, noting that ‘by doing so her name would be perpetuated for all time’.

Eight months later, Ruth died with Arnold by her bedside. The watch was duly transferred to the Company’s collection and ended up on display at Guildhall.

Now I needn’t go to Guildhall to see Arnold—delightful though my visits there always were—but instead I can pop into the magnificent new gallery at the Science Museum during my lunch break.

I hope you’ll have a chance to see it too.

Inaugural meeting of the AHS Wristwatch Group

This post was written by Mat Craddock

On Thursday 29th October, the AHS’s first new Group in over forty years held its inaugural event.

The Wristwatch Group, whose aim is to further research into, and to increase the understanding of, wristwatches, has been working with one of the oldest and prestigious names in watches, Montres Breguet SA, to host the event.

Breguet’s newly-opened three storey boutique on Old Bond Street was the perfect venue, with vintage pieces on display alongside current models, many clearly showing a direct lineage from Abraham Louis’ extraordinary and often revolutionary designs.

One of Breguet’s in-house watchmakers guided guests through the often bewildering complications and materials on these modern watches, which are now just as likely to be using titanium and silicon, as brass or gold, such as the Breguet Tradition 7077.

This fascinating new piece is a bifurcated model with two movements working independently at different frequencies: a relatively traditional time-only mechanism (3Hz); and a 20-minute chronograph operating at 5Hz.

The evening was introduced by Jonathan Betts MBE on behalf of the Chairman of the Council, and was followed by two talks by two of this country’s most knowledgeable Breguet experts, Andrew Crisford and Stuart Kerr.

Jonathan’s introduction also paid respect to AHS President Lisa Jardine, a firm supporter of the Group, who had sadly passed away a few days before.

Andrew drew parallels between modern wristwatch marketing practices, such as product placement, the use of brand ambassadors and accessorising, and the pioneering efforts by Abraham Louis.

It seems that even in the early 19th century, Breguet was ahead of the game. Stuart began his talk by describing the circumstances that lead to the Longitude Act, via the alleged murder of Sir Cloudesley Shovell on the sands of Porthellick Cove. Shovell’s pocket watch, an English verge had recently been brought into the boutique and was, along with some of Andrew’s Breguet-related paraphernalia, available for guests to view.

Watching over us

This post was written by David Thompson

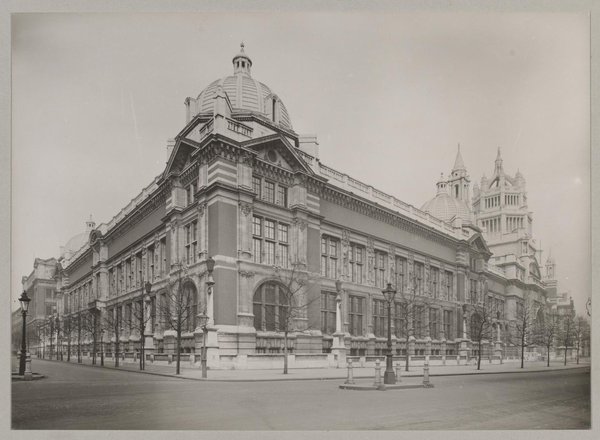

Walking up Exhibition Road in London on the way to the Science Museum, you just have to look to your right and up a bit, and there stands one of our great horological giants.

On the façade of the Victoria & Albert Museum stand a cohort of celebrated figures in Britain’s manufacturing heritage. Thomas Tompion is there amongst some illustrious company.

On his left and right are St. Dunstan, the Patron Saint of craftsmen, sculptor William Torell, printer, William Caxton, goldsmith George Heriot, blacksmith, Huntingdon Shaw, cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale, potter, Josiah Wedgwood, bookbinder, Roger Payne and designer, William Morris.

These figures, finely sculpted in Portland stone, make up part of the museum’s façade designed by Aston Webb and begun in 1899 when Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone.

However, it was not to be until 1909 that King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra officially opened the new building.

The figure of Tompion was sculpted by Abraham Broadbent (1868-1919).

He was born in Shipley, the son of a stonemason. He studied in London at the South London Technical School of Art and went on to become one of the more celebrated sculptors of his time, particularly in works in the baroque style.

Looking at Broadbent’s image of Tompion, however, it would seem that he had no access to the well-known mezzotint portrait of Tompion by John Smith after a portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Tompion is depicted holding a watch in his left hand, and what appears to be a magnifying glass in his right hand. It would seem that Broadbent did not discuss his proposed figure with a watchmaker, even in the late 19th century, such a visual aid was not the preferred instrument.

Nevertheless, it is great to see that one of the clock and watchmaking giants is there amongst a pantheon of recognized celebrities.

For a detailed account of all the Victoria & Albert Museum sculptures around the building façade, see http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/misc/va/facade.html

Sushi, saké and a send-off

This post was written by James Nye

December 2014’s Antiquarian Horology featured a clock made in 1573 by De Troestenbergh in Brussels, rebadged and given as a gift (by Spanish survivors of a 1609 shipwreck off Japan) to the great Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

In May 2014, Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks worked on conserving the clock in a Japanese shrine, its home since the early 17th century, measuring and photographing everything.

The authorities wanted more than just conservation – they wanted a replica of the movement, sitting alongside, so that visitors could understand the magic of this striking and alarm clock, four centuries old and plaything of their most revered Shogun.

In August 2015, Johan and David Thompson (the project’s ambassadorial godfather) travelled to Japan to witness the significant honour accorded to the replica on its arrival and installation.

This was no ordinary project. Johan could only rely on details taken over a week.

From mid-2014 to mid-2015, he devoted hours ultimately uncountable to producing a working copy of the movement. Pillars were turned with a hand graver, fusees roughly filed out by hand, flies cut and filed from the solid, shaped plates pierced out of steel plate, and so on.

Wheel teeth were formed using modern cutters, and modern machinery played a large role, but it was a year spent file-in-hand, forming, shaping and finishing.

Others contributed – notably the Whitechapel Bell Foundry for the bell, while the solid silver dial and hour hand were decorated by members of the Hand Engravers Association.

The original sits in a shrine, while Johan entered near monastic isolation for a year.

In August 2015, to mark his own long journey, to thank the many who had helped, and also to enlighten friends who had not seen him for months, The Clockworks hosted an evening of sushi, saké and Asahi. This was a chance to see the working replica before its long journey to Shizuoka, joining De Troestenbergh’s original.

It was a great evening, celebrating the traditional internationalism of horology in which a Dutchman in London worked to an ancient Flemish design to produce a clock for a Japanese shrine.

Campai!

BHI Clock & Watch Conservation and Restoration Forum, 5th September 2015

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Earlier this month the British Horological Institute hosted a day of lectures and discussion relating to horological conservation and restoration at their headquarters in Upton Hall.

![Upton Hall, headquarters of the BHI (Image: Andy Stephenson [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/Upton_Hall_-_geograph.org_.uk_-_4563-1.width-600.jpg)

The terms 'conservation' and 'restoration' are applied to different philosophies of approach to maintaining and repairing objects.

Conservation typically describes an approach of minimal intervention, i.e. attempts to preserve the existing material of a clock or watch as far as possible, whilst still enabling it to serve its required use.

Restoration can describe attempts to revert a clock or watch (that has received alterations over the years) back to its conjectured original state. This typically involves involves the alteration or removal of existing material which, even if not original to the object, can be considered to be part of its history.

There are proponents and opponents of each approach, with many falling somewhere in-between.

There is no black or right – every conservation project is different. The differing motives of the stakeholders (who might include horologists and their clients, or visitors to a museum) and the intended use of an object are all valid considerations in the decision-making process which affects the outcome of a project.

The forum aimed to explore these issues through a series of talks from professionals in the field.

The AHS was very well represented with six of the seven speakers being members:

Ken Cobb – Welcome and Introduction

Alison Richmond – ICON’s Perspectives

Matthew Read – Conservation Training and Education in Horology

Oliver Cooke – Managing Dynamic Objects in Museum Collections

Chris McKay – Conservation on Larger Objects (Turret Clocks)

Keith Scobie-Youngs – Working with Others – Project Management within Conservation

Jonathan Betts – Conservation/Restoration for the National Trust and Other Heritage Organisations

The forum ended with a positive and interesting open panel discussion.

One of the key messages of the day was that the BHI and all horological practitioners have a key role in helping to educate, as widely as possible, all stakeholders in the conservation process on these issues because only with this knowledge might they know how their decisions in the present will affect our heritage in the future.

The forum was thus a very positive contribution towards this vital aspect of antiquarian horology and Kenneth Cobb and the BHI must be lauded for making it happen.

Taking the first watch

This post was written by Mat Craddock

It’s possible that we may never know for sure when the first wristwatch was made, although that hasn’t stopped a number of Swiss brands laying claim to the production of some iteration of that ur-device.

The Patek Philippe N° 27’368 is such a piece – a six line, gilt, cylinder escapement encased in a rectangular gold bracelet with a hinged, hunter-style cover – although it’s not clear who originally commissioned it from Antoine Norbert de Patek and Jean Adrien Philippe.

The watch is usually behind the well-maintained glass of the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, so it was wonderful to be able to see it as part of the Watch Art Grand Exhibition in London’s Saatchi Gallery during May.

This exhibition took the visitor through an immersive area showing an introductory film, introduced them to metier d’arts and other decorative skills, and included over 400 pieces, from automata to automatics, which spanned almost five hundred years of watchmaking.

At the end of the route, British watchmakers answered visitors’ questions about case refinishing, movement assembly and the chiming mechanism of a minute repeater movement.

Patek N° 27’368 was made primarily as a timepiece to be worn on the wrist, rather than as a piece of jewellery (i.e. the bracelet is of secondary importance). That must have required, one imagines, a great leap of faith on the part of Messrs Patek and Philippe.

While wristwatches gained popularity with women during the 1880s and 90s, and were also produced for men as military timekeepers during a similar period, the earlier oblong-shaped repeater for wristlet sold to the Queen of Naples on 5th December 1811 by Breguet, appeared to have made no horological or sociological impact at all.

N° 27’368 was finally sold to the Countess on November 13, 1876, some eight years after it had first been built.

Chronometers in hell

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In my previous post, ‘Having a smashing time’, we saw how watches are being tested for shock resistance, which can involve some pretty heavy handling.

Another method of testing timepieces is prolonged exposure to heat and cold. This was especially important for marine chronometers, who would travel to all parts of the globe, so it was important to determine to what degree their rate was affected by temperature fluctuations.

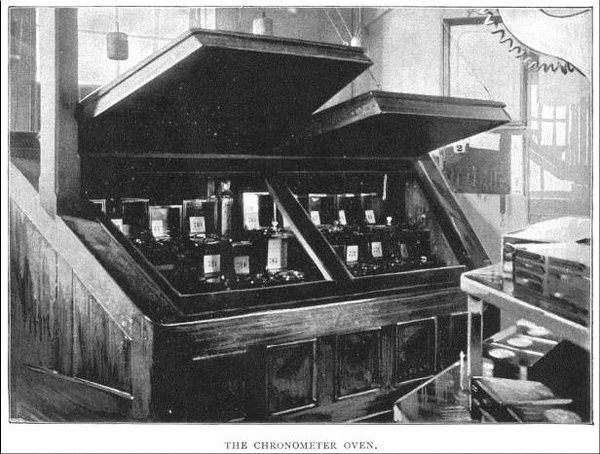

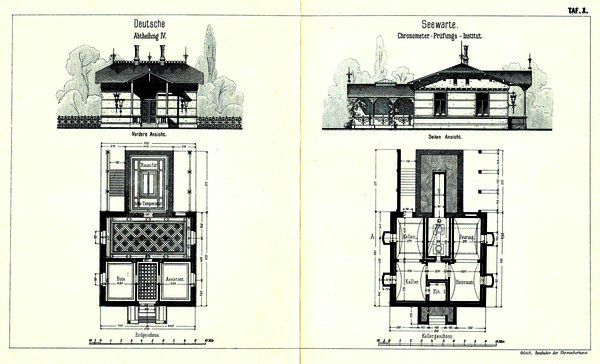

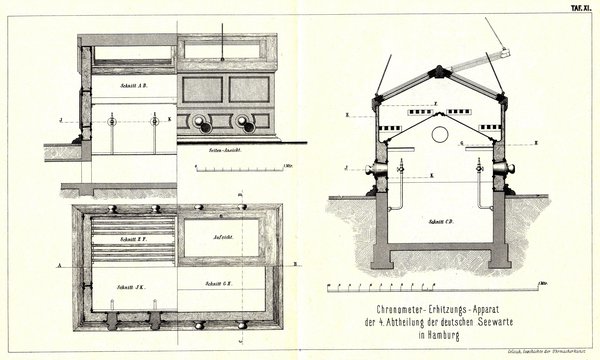

The Time Department at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where the rate of chronometers was tested, had a large oven in which chronometers were kept for eight weeks at a temperature of about 85 or 90 degrees Fahrenheit, that is around 30 degrees Celsius.

A recent article in Antiquarian Horology had a section on chronometer testing facilities in 19th-century Germany.

In Hamburg they had both an ice cellar and a gas-heated oven. The naval observatory in Wilhelmshaven was less well equipped:

'Neither an ice cellar nor a heating apparatus was available. The radiators of the central heating acted as makeshift for the latter, and tests in lower temperatures were conducted in winter by opening the windows. Sometimes the required temperature of 5º could not be reached due to mild weather'.

Manufacturers of chronometers could have their own heat and cold testing apparatus.

An oven and an ice-box used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons are in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. Normally these two objects are kept in storage, but some years ago they were taken out for display in a temporary exhibition ‘Time Machines’.

When I visited the exhibition, the curator, Dr Stephen Johnston, told me that at first sight some visitors thought the ice box was a toilet!

Sir George Airy, the late Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, in one of his popular lectures drew a humorous comparison between the unhappy chronometers, thus doomed to trial, now in heat and now in frost, and the lost spirits whom Dante describes as alternately plunged in flame and ice.

He was referring to Dante’s La Divina Comedia, Book One: Hell, III, 76-82:

'There, steering toward us in an ancient ferry came an old man with a white bush of hair, bellowing: “Woe to you depraved souls! Bury here and forever all hope of Paradise: I come to lead you to the other shore, into eternal dark, into fire and ice.”'

Commemorating an invasion that never happened

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

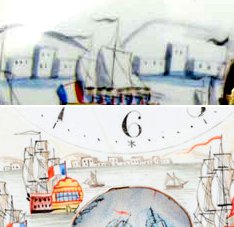

Last month saw the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic era. To mark the anniversary, this week’s blog posting looks at two curious watch dials. The unusual point being that they both appear to come from the same manufacturer, but were made to celebrate victories on both sides of the conflict. One of which never happened.

The first of the two watch dials was made around 1798 when the prospect of a French invasion of England was real and, for many, a terrifying prospect.

Rumours abounded of the French rafts that would carry tens of thousands of troops and weapons to English shores. The images of these vessels distributed by the printmakers ranged from the allegedly factual to the overtly ridiculous.

The French perspective was bullish about the prospect of invasion. Not only were they confident of success, but they also believed that the English would, for the most part, welcome the invasion.

Gillray’s print (above) records that there were indeed those who may have welcomed the French. Whig collaborators are shown on the right-hand-side of the picture trying to winch the French transporter ashore and their efforts are being foiled by Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, seen as the wind blowing the flotilla to destruction.

The dial depicts the ‘descente en Angleterre’ with a more traditional fleet of ships sailing towards the heavily defended English shoreline and serves as a useful glimpse into the mind of the manufacturer, keen to capitalize on the bullish French mood of early 1798.

The scene on the second dial is identifiable as the Battle of the Nile because of the burning ship on the left-hand-side of the image. This represents the French Flagship, L’Orient, which exploded with such violence that fighting was temporarily halted and it became a symbolic feature in popular representations of the Battle.

There is a near-identical row of box-shaped buildings placed along the horizon on both dials. This suggests that they both came from the same source. Such buildings seem more appropriate for the northern coast of Africa than the southern shores of Britain and so it was probably a generic depiction preferred by the artist.

As an asides, the invasion watch dial has a later counterpart in the Museum’s medal collection. A rare sample medal was struck in 1804 with dies intended to be used in London by the victorious French conquerors. Despite amassing a substantial force in the Boulogne area, the embarkation was prevented, principally by the diversion of troops and resources to the Battle of Ulm and, secondarily, by the English blockades.

Inspired reforms – magnificent outcomes

This post was written by James Nye

In May 2014, I blogged about a competition to devise uses for new-old stock 1950s Calibre 5000 Reform movements that had turned up at the annual Mannheim electro-fair.

I judged the entries on 24 May this year, and what an amazing event to witness. Here was a beautifully executed movement, simple, reliable, long-lived, but criminal to hide.

How to incorporate it in a modern design, and achieve a functional clock, when the attractive side of the movement would necessarily normally face the rear? In significant style, it turns out……

Ivo Creutzfeldt ignored convention and went for pure schlock with his tongue-in-cheek ‘winged chariot entry’.

Thomas Schraven offered a couple of entries, one channelling a strong modernist theme – using two movements, one for display, the other for timekeeping.

Eddy Odell showed considerable lateral thought, introducing the movement into a glass mug, keeping the movement visible to the top, while driving digital minute and hour bands in the base, the battery neatly hidden.

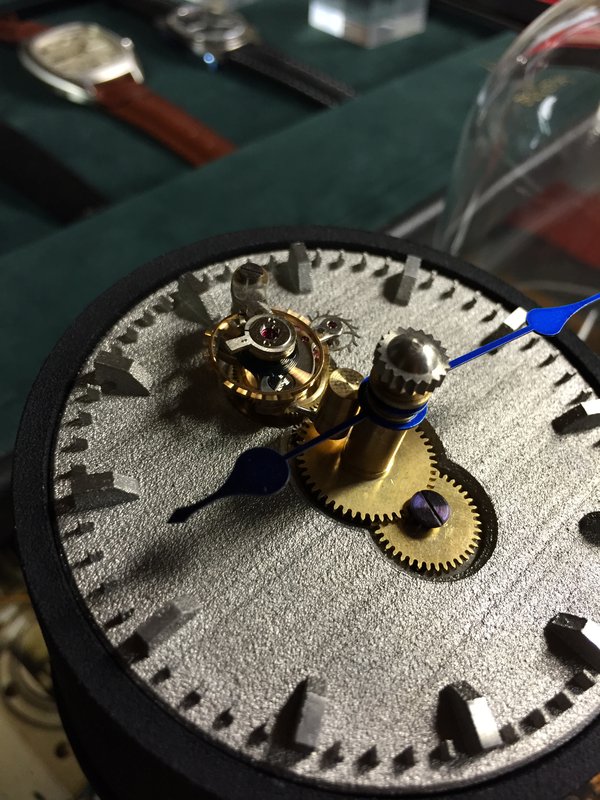

Till Lotterman and his home team colleagues offered a remarkable test exercise. Using original parts, they recut elements to form a tourbillon, brought out on the dial side of the movement, achieving real spectacle ( film here).

Not only this, they 3D printed a stylish stainless steel dial, and also 3D printed an open-sided plastic tubular case, with internal mirror to reflect the movement. Later we were treated to a lecture on the extraordinary possibilities emerging for 3D printing.

Finally, the most talked about item in the competition, Frank Dunkel’s inspired diorama clock, using the Reform at the centre of a roundabout, driving hidden arms carrying neodymium magnets, in turn propelling a VW Beetle (minutes) and VW van (hours) against perimeter hour markers ( film here ).

Power even arrives by wire supported on telegraph poles. Absolutely inspired!

The whole party retired to a restaurant for the evening, at which, amidst characteristically heroic levels of consumption, we celebrated the amazing results of our competition – prizes all round.

AHS Wristwatch Group

This post was written by Laura Turner and Rebecca Struthers

The Antiquarian Horological Society is pleased to announce the formation of a new specialist group focusing on the emergence and development of the wristwatch.

There has been an increased interest in vintage and antique wristwatches in recent years, but a perceived lack of corresponding published scholarly research. The Wristwatch group plans to promote and encourage the study of the history and development of wristwatches, through meetings, education and publications, including articles in the Journal or technical papers for Group members.

Members of the Wristwatch Group will have regular meetings, in the form of lectures, short talks, bring and discuss sessions, and visits to exhibitions, private collections and centres for the practice and study of watchmaking both in the UK and abroad.

The Group will bring together enthusiasts keen to learn more about the origins, makers, techniques, family and corporate histories and indeed any of the material and cultural aspects associated with wristwatches.

All are welcome, whether new to the subject or recognized authorities.

The group will be chaired by Rebecca Struthers, watchmaker and doctoral researcher of antiquarian horology at Birmingham City University, along with Laura Turner (secretary), one of the curators of the Horological Collection at the British Museum, supported by Mat Craddock, and Tracey Llewellyn, editor-in-chief of specialist wristwatch publication Revolution magazine.

Announcements of forthcoming Group meetings (and subsequent meeting reports) will be included in Antiquarian Horology, and will be listed at www.ahsoc.org and via our subscription mailing list.

Membership of the Group is open to any member of The Antiquarian Horological Society.

To join the Wristwatch Group, or to find out more, please email wwg@ahsoc.org.

Plastics in horology- AHS funded PCIP course

This post was written by Tabea Rude

In order to gain a wider understanding of the conservation of plastics, its history and its newest applications, the AHS recently paid for me to attend the Conservation of Plastics short course taught by Yvonne Shashoua at West Dean College.

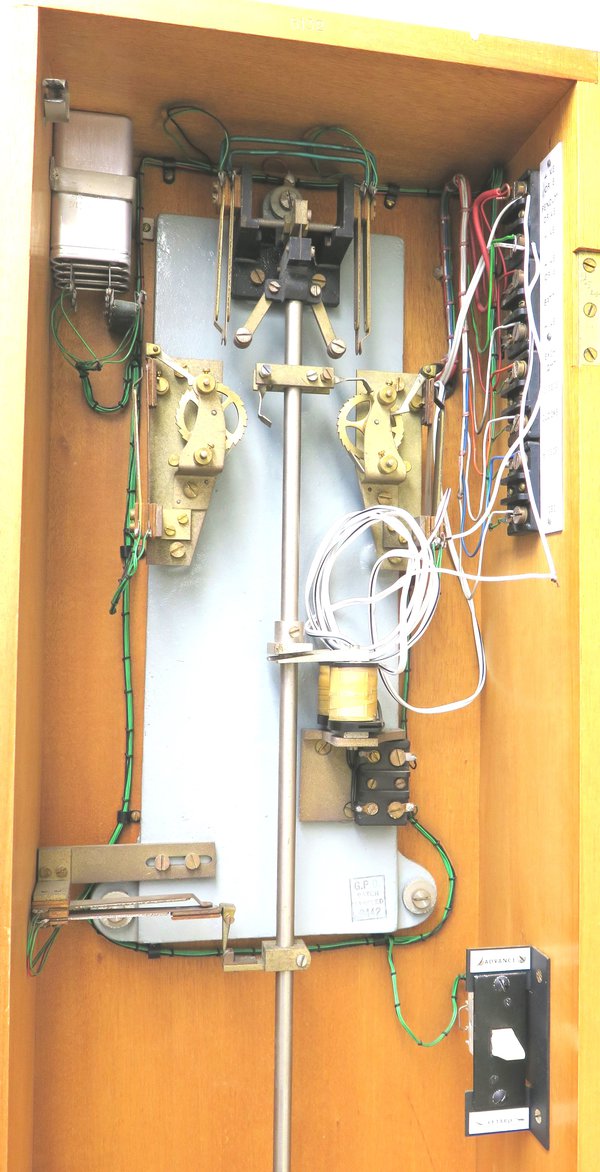

This course proved to be advantageous for an investigation of the degradation of insulation materials in Post Office Type 36 time transmitters as part of the MA Conservation Studies programme at West Dean College.

During the course it became evident how interlinked plastics are with our life.

Starting off as a random material with varying compositions, cooked up in private households it developed to a diverse material invading every corner of our universe.

As a material between waste and high precision engineering, plastics are subject to multiple dilemmas, one of them being its conservation for future generations.

As part of the course, identification techniques were discussed and carried out. By exploring the properties of different plastic families, it became clear that a mixed media object such as the Post Office Type 36 time transmitter, containing at least five different types of plastics, metals and wood, would challenge preventive conservation techniques.

Some plastics such as PVC, often used for wiring in the PO Type 36, should be kept enclosed to avoid the loss of plasticiser. However, other plastics, that tend to off-gas, should be subject to an absorbent such as Zeolite, Silica gel or activated carbon.

On that account preventive conservation of mixed media objects such as the PO Type 36 is at best a compromise.

As a result, this course was an eye-opener to a material we take for granted today. Experiments conducted within the framework of the PO Type 36 study were significantly influenced and informed by the course and discussions had with conservators working in the field of plastics.

Permission to come aboard

This post was written by David Thompson

All made in the 1580s, there are three surviving clock-automata in the form of medieval ships, made by Hans Schlottheim in Nuremberg.

One, a silver nef made for the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

A second, larger and more elaborate example in gilded copper exists in the Musée de La Renaissance in the Chateau d’Écouen near Paris.

The third example similar in many ways to the Écouen nef, resides in the British Museum.

These automata ships were made as table decorations designed to trundle along the banquet table playing music and firing their cannons at the end of their performances. What a way to impress your dinner guests in the 1580s.

Looking at the British Museum nef, it is clear that, with the exception of just one figure standing on the upper rear deck, all the figures on the ship are more recent cast copies of this one original.

One of the problems with automata such as this is what happened when they went out of fashion. Clearly such a thing could not be shown as an impressive demonstration of wealth at banquets time after time.

It is known that the Augustus, Elector of Saxony (1526-1586) had one of these table entertainments – there is a detailed description of just such a machine in the inventories of the Elector’s Kunstkammer from the 1580s. But what happened later?

You can just hear one of the guests at a second outing of the nef saying 'come on Augustus, we’ve all seen that, don’t you have anything new for us?'

When the nef, became less of a wonder and more of a curiosity, you can imagine a small child insisting that the figures be removed so that they could be played with individually. After all, the machine itself had ceased to function properly years ago.

This is speculation of course, but it might well explain the absence of figures on the ship when it appeared in England in 1866 and was bought by Octavius Morgan MP who then gave it to the British Museum.

Intriguingly, in 1983 a figure came up at auction in London and investigation suggested that there was every possibility that the figure was an original from the nef in the British Museum.

It was purchased by Rainer Zeitz Limited, but when they heard about the possibility that it came originally from the British Museum nef, they very kindly donated it to the collections.

For more information on these wonderful machines, see:-

http://musee-renaissance.fr/objet/nef-automate-dite-de-charles-quint

http://www.khm.at/en/visit/collections/kunstkammer-wien/

Julia Fritch (ed), Ships of Curiosity , Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2001.

The AHS 2015 Annual Meeting

This post was written by David Rooney

We welcomed over 100 members and guests to a packed full house at the National Maritime Museum for our 2015 Annual Meeting last Saturday. The sun shone, the atmosphere was buzzing, and we were given a superb day of talks and conversation.

The theme this year was ‘time and transport’ and, outside the museum, AHS members had brought a stunning selection of vintage cars to help set the scene.

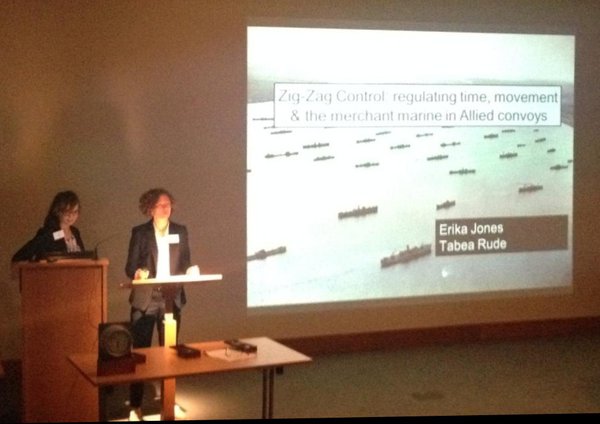

During the morning session, we had fascinating talks by Peter Burt on RGS explorers’ watches; Tabea Rude and Erika Jones on zig-zag control; and Rory McEvoy on a Perregaux advertising campaign (apologies for the poor quality indoor photographs!)

After lunch and the society’s AGM, we heard from our new President, Lisa Jardine, on sea-going clocks; Jonathan Betts on polar expedition chronometers; and James Nye on the history of car clocks.

We were delighted to learn that Professor Jardine has recently been made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society.

We also marked the handover of the chairing of the society from David Thompson to James Nye by seeing David awarded a Fellowship of the AHS. Our huge congratulations and thanks to Lisa, David and James.

It was great to see so many members and guests from all around the country, of all ages and with all sorts of interests—represented also in the wonderful variety of speakers and lectures.

Thanks to you all for coming—and we look forward to the coming year with great excitement!

Can bonded solid lubricants preserve the teeth of running clocks?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Antiquarian clocks are still in widespread use. However, like any machine, mechanical clocks wear out as they run and, to keep them running, repairs will inevitably be necessary.

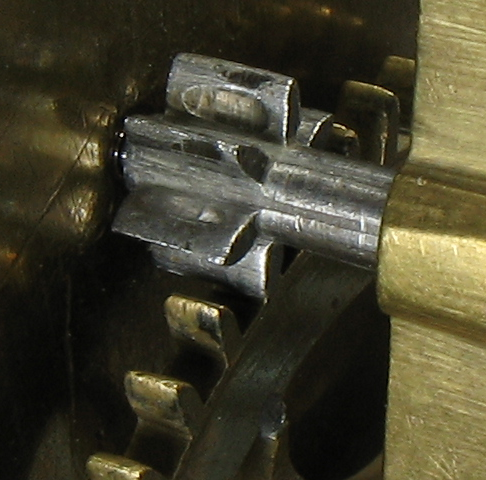

The image above shows a three century old longcase clock pinion that is well worn. Such a change in form will hinder the correct running of the clock until, eventually, it may no longer run at all.

Current repair techniques involve replacing the lost material or the whole gear. Either method is likely to result in loss of evidence of the clockmaker’s original work. This information is important as it can help us to assess the authenticity and origins of clocks.

It would therefore be useful to find a way to reduce the wearing of the teeth in the first place.

Liquid lubricants, e.g. oils, are generally not used on the teeth of clock gears as they are typically exposed to the air, from which dust can mix with the oil to form an abrasive, or chemicals can form which can corrode gears.

Bonded solid lubricants (B.S.L.s) are dry and do not absorb contaminants from the air. B.S.L.s contain particles of dry lubricant, such as graphite, suspended in a binding agent, such as epoxy resin.

They are applied as a liquid which cures to form a hard, dry coating. This coating can both lubricate and act as a sacrificial wearing layer. B.S.L.s might therefore be a useful treatment for preserving the gears of clocks.

Over the last year at the British Museum, where we run antiquarian clocks in the gallery, I have been conducting trials of B.S.L.s on model gear teeth as part of an MA Programme in Conservation Studies at West Dean College.

The B.S.L. that was tested was found to reduce wear compared to uncoated gear teeth. However, scientific analysis showed that it contained chemicals that are unsuitable for use on historic parts.

There are however many other types of B.S.L. and, given the promising results, I plan to test more. It is hoped that this will eventually lead to a treatment to help to keep the antiquarian clocks running with their original gears.

Look out for more information in future editions of our journal, Antiquarian Horology.

Having a smashing time

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

On my twelfth birthday I was given my first watch.

I remember that it had the word ‘shockproof’ stamped on the back and that I wondered just how ‘shockproof’ it was. Mercifully I did not try to determine the limits of what it could take.

On Wikipedia I find that ‘shockproof’ should be understood as ‘shock resistant’, and that there is an international standard which specifies the minimum requirements and describes the corresponding method of test.

It is based on the simulation of the shock received by a watch on falling accidentally from a height of 1m on to a horizontal hardwood surface.

In the test the shock is usually delivered by a hard plastic hammer mounted as a pendulum. Some manufacturers are more ambitious.

Under the heading ‘Having a smashing time: Making sure your watch stands the test of time’ a newspaper article describes and illustrates the many types of torture to which the Swiss factory of IWC (International Watch Company) subjects its timepieces.

The impact test is illustrated here with images from the article. A metal pivot, weighted with a 10kg block, is pulled upright, then swings round to hit a watch held in a vice. A cotton sheet is laid out to catch the watch, and technicians check after each impact to see that it’s still ticking perfectly.

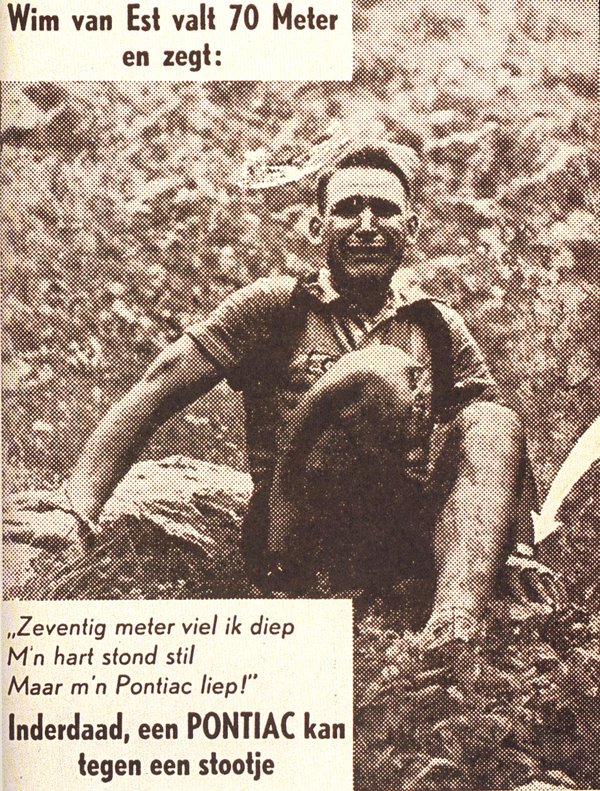

A less carefully planned demonstration of the shock resistance of a watch was given during the 1951 Tour de France, the annual cycle race.

The watch manufacturer Pontiac had sponsored the Dutch team by supplying them with wristwatches. One runner fell and dropped seventy meters down the side of the mountain.

Amazingly, he was not seriously injured. Even better for the sponsor, his watch was still ticking. Pontiac made a successful publicity campaign out of it.