The AHS Blog

The worst of times

This post was written by James Nye

I have been musing on the destructive power of war in the lives of various clockmakers and their families.

Consider an obscure Brno clockmaker, Johann Antel (1866–1930). Sporting a boater, his two daughters, Anna and Edith, are ranged left and right – circa 1913. The Antels, from Bohemia, had long German ancestry. In the Great War, Johan lacked vital materials for important commissions. When he died in 1930, the local clockmakers, ethnic Czechs and Germans, all stood for a minute’s silence.

The Nazis arrived in 1938 and it was expedient to prove Germanic ancestry. The archives record the remaining family’s declarations. Daughter Anna had been an apprentice in her dad’s clock shop in Brno, so she was now in charge, along with her mother Ludmilla.

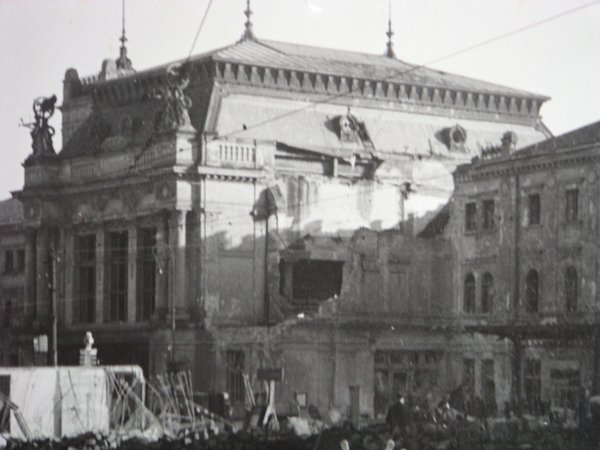

With the arrival of war, nothing was safe – even clock shops were bombed – witness the damage to the Antels’ place.

When war ended, the rules changed. Being Czech was suddenly useful and extraordinarily the archives record sister Edith declaring precisely that, and succeeding because she had sheltered a Jewish engineer, Ing. Michaelstadter, whom she duly married.

She stayed in Brno, dying in 1981, while her ‘German’ sister Anna had to flee to Vienna for the rest of her days, dying in 1984.

We only know about Antel because of a 1944 RAF raid on Brno, which set in train a series of events, leading to the station clock emerging in the 1990s.

But war is not a one-way street. What about the Luftwaffe over London? A 1941 raid caused the dramatic collapse of 19–21 Queen Victoria St, taking Standard Time with it.

In an archive last week, I realised that exactly the same raid flattened Samuel Smith’s old jewellery shop on Newington Causeway.

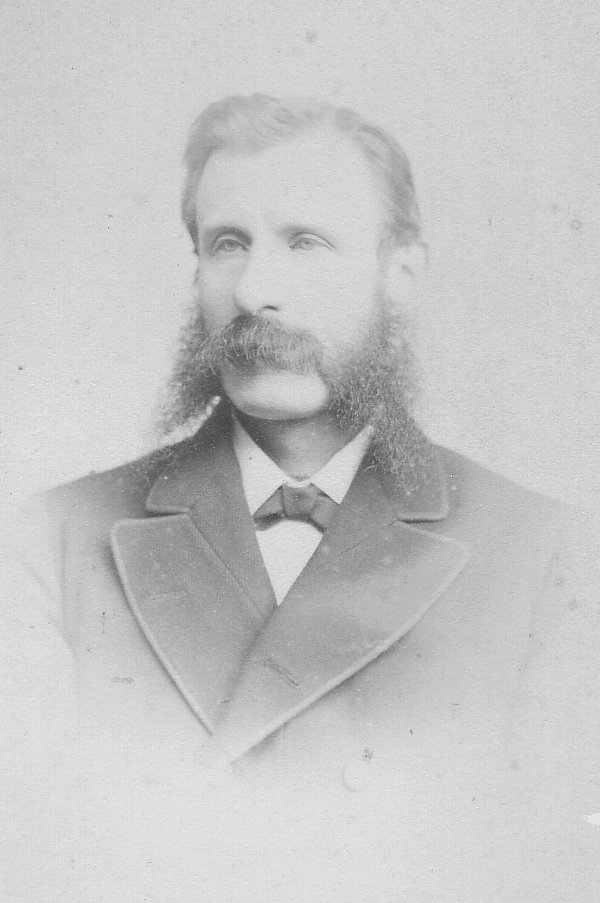

John Hoch (1836–1918) worked there for Samuel Smith in the 1870s. Originally from Rheinland-Pfalz, he lived in London, with magnificent sideburns, for the rest of his life. But he was in the wrong place at the wrong time in 1914 and anti-German feeling made life very hard – some of his children even changed their surnames and emigrated.

Hoch didn’t quite make it to the Armistice, dying in the summer of 1918. But you can call on him in Norwood cemetery.

The Silver Swan fictionalized

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The latest novel by the Australian author Peter Carey, The Chemistry of Tears, was inspired by the Silver Swan of Bowes project.

The Swan is an amazing late 18th-century, life-sized automaton, incorporating three clockwork mechanisms or movements, products of the clockmaking trade. It has been in the Bowes Museum in County Durham, Northeast England, since 1872 where it can be seen in action every afternoon.

In 2008, the Swan underwent a major conservation project, undertaken by our Council member Matthew Read. In 2010 he gave a fascinating talk on the subject for our Society, and recently he went back to Bowes to see that all was well, as reported in his blog ‘Friends Reunited’.

The story in the novel goes back and forth between the 19th century and the present. An Englishman commissions an automaton to be made in Germany. It’s inspired on Vaucanson’s famous digesting duck automaton, but somehow turns out as a (the?) swan – it’s all a bit unclear.

In modern London, a conservator in a fictional museum is given the task of restoring the by now dismantled automaton to working order. Her manager has set her this challenge, hoping it will take her mind off her grief over her lover’s sudden death.

Does it work as a piece of fiction? I am not sure. But what I am sure of is that there cannot be many novels that explicitly mention our journal:

'It was then, high on grief and rage, I stole two of Henry Brandling’s exercise books. What would happen if I was caught? Burn me alive, I didn’t care. I tucked them inside my copy of Antiquarian Horology, and walked straight past Security and out into the London street which was now, in late April, hotter than Bangkok' (p. 34).

If anyone knows another novel in which our journal occurs, please leave a comment!

Antiquarian horology in a graveyard

This post was written by David Rooney

Last weekend I went for a walk around King’s Cross and St Pancras, London. The area’s undergoing great change right now as part of a huge regeneration project. I was on the hunt for the mausoleum of one of the world’s greatest antiquarian collectors, Sir John Soane.

One of my most cherished places is the Soane museum in London, presented to the nation in 1833. Soane’s collection there is quite remarkable.

Sarcophagus in the basement? Check. Hogarths and Turners lining the walls? Check. The most exquisite juxtapositions and delightful sight-lines? Check, check, check. It’s a place like nowhere else. Go often!

My particular reason for viewing Soane’s tomb was that it was used by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott as inspiration for his famous red ‘K2’ telephone kiosk. I like things like that.

So far, so antiquarian. But where’s the horology? Well, I was on my way out of St Pancras Gardens, where Soane’s memorial sits, when I encountered a memorial sundial erected in 1879 by Baroness Burdett-Coutts, one of the great Victorian philanthropists and an early supporter of the British Horological Institute.

Isn’t it priceless? The sundial is inscribed, ‘tempus edax rerum’, or, ‘time is the devourer of all things’.

I was struck by the calm atmosphere of the gardens set amidst blocks of housing, the railway lines out of St Pancras, a hospital and the general bustle of London. I think the calmness came in part from the embedded memories in the memorials and inscriptions, which were often moving.

Time is the devourer of things. But we have found ways to use things in order to remember. Periodically, they might be reconfigured, as Soane’s tomb became a telephone kiosk. But that’s just our way of killing time.

Lighting up time

This post was written by David Thompson

The story of the night clock, a device which allows the time to be seen in the dark is a long one.

In this modern era of instant electric light, it is easy to forget that in earlier times, getting light at night was quite an involved business. So what better way to solve the problem than to have a clock which was illuminated all through the hours of darkness.

One of the earliest examples of these clocks was that invented by the Campani brothers, Giuseppe, Pietro Tomasso and Matteo Campani from San Felice in Umbria, who worked in Rome in the second half of the 17th century.

However, one clock which caught my attention was a much later, metal cased clock in the form of a Greek urn in which was placed a light source –oil lamp or candle, and which had a system of lenses to project an image of the dial onto a wall in the room.

The clock was made and retailed by the inventor and optical instrument maker Karl August Schmalkalder, born on 29th March 1781, in Stuttgart, Germany. He came to England in about 1800 where he anglicised his name and in later years worked in partnership with his son John Thomas Schmalcalder. On his retirement in 1839 the business was continued by his son.

Charles Augustus married Charlotte Ann Cochran on May 24, 1804, in St Andrews church, Holborn and he died on December 25, 1843 in the Strand Union Workhouse – although he is renowned for his patented prismatic compass, a mechanical drawing device, optical instruments and barometers, sadly his genius did not make him a rich man.

Whilst the Schmalcalder name appears on the clock dial where he describes himself as ‘Patentee’. I have failed to find a patent in that name for this device – it may be that he is simply telling his customers that he is a holder of patents not specifically for this illuminating device.

For a detailed account of the Schmalcalders, although without detail of this clock see – Julian Smith, ‘The Schmalcalders of London and the Priddis Dial’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Volume 87, No.1, 1993, pp. 4-13.

For more information on the Charles Augustus Schmalcalder, see the family history website created by Steve Smallcalder.

Friends reunited?

This post was written by Matthew Read

Revisiting the Bowes Swan this week – the first time since it was completely disassembled in 2008 – was a personal and surprisingly profound experience.

There is a blogged account of the 2008 conservation project on the web site of the Bowes Museum. That project was at least from my perspective, a commercial professional endeavour, and very hard work!

As the intervening years have passed, some of that professional objectivity has slipped and allowed the Swan and the wonderful Bowes museum to become part of me. Yes, and of course, one can dine out on a project like that for a very long time indeed.

However, snapping back to hard reality, the swan is a bunch of clockwork, levers, cams and ingenuity, and the purpose of this recent visit was to see how everything has stood up to nearly four years of use.

The automaton being played once a day every day the museum is open to the public. Well, of course, as would be expected, it’s a mixed bag. Heavily loaded bearings and working surfaces take the brunt, some mid-twentieth century restorations do not fit quite so comfortably with the eighteenth century, yet overall, the policy of maintenance, observation and importantly, engagement by staff at the museum, seems to be striking that very fine balance between cost (in the widest sense)and benefit.

So the show goes on, the public watch, children stare, almost everyone films and photographs, and often the daily performance receives a round of applause. If you haven’t already, you really should see the sensual and magical swan in action. The Swan is operated daily at 2.00 pm.

Waking up with a bang

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

In my own time I am Adviser to the National Trust on the care and curatorship of their clocks and watches, and occasionally the Trust’s Advisers on different disciplines are called upon to work together.

Clocks and Firearms might seem an improbable combination, but one object in the Trust’s collections recently brought me and Brian Godwin (Adviser on Firearms) together for a most interesting study day.

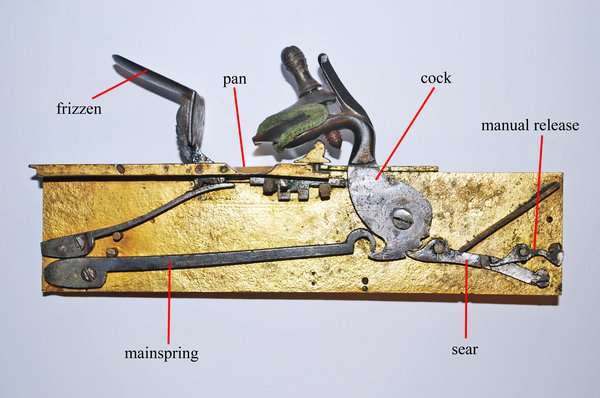

Snowshill Manor, a house full of surprises, was, almost inevitably, the source of the object in question – a little gilt-brass table clock with alarm, made about 1740 and signed by Peter Mornier, London. The Trust has any number of clocks with alarm mechanisms, but this particular example has an additional feature, guaranteed to have the owner out of the deepest slumber in a trice.

As with most alarm clocks of the period, the clock sounds a bell at the appointed hour, but then, a flintlock mechanism is triggered and, with a flash and a bang, a lighted candle swings up from a compartment within, jack-in-a-box style, and illuminates the bedside. In fact, if the candle isn’t securely fixed in its swivelling socket inside the clock, there is a distinct possibility it is projected onto the bed itself, guaranteed to have the occupant up and about.

The mission of the two Advisers included a desire to see – and film – the clock working, if at all possible. Needless to say, careful preparation was required to ensure the clock itself was safe and the test was carried out in a brick-lined vault at the back of the Manor, although only a tiny quantity of black powder is needed to fuel the flintlock.

In the event however, not a single ignition took place, as the flintlock’s frizzen (the hardened steel plate against which the flint is supposed to strike the sparks) appeared to be too worn already, and would not oblige. It seems the clock has done its fair share of early morning duties over the years and is entitled to take an extended rest.

A few more experiments will take place to see if we can’t persuade it to perform just once more for the cameras; meanwhile further research on the clock, on Mornier, and on other examples of this kind, is underway and will be written up in Antiquarian Horology in due course.

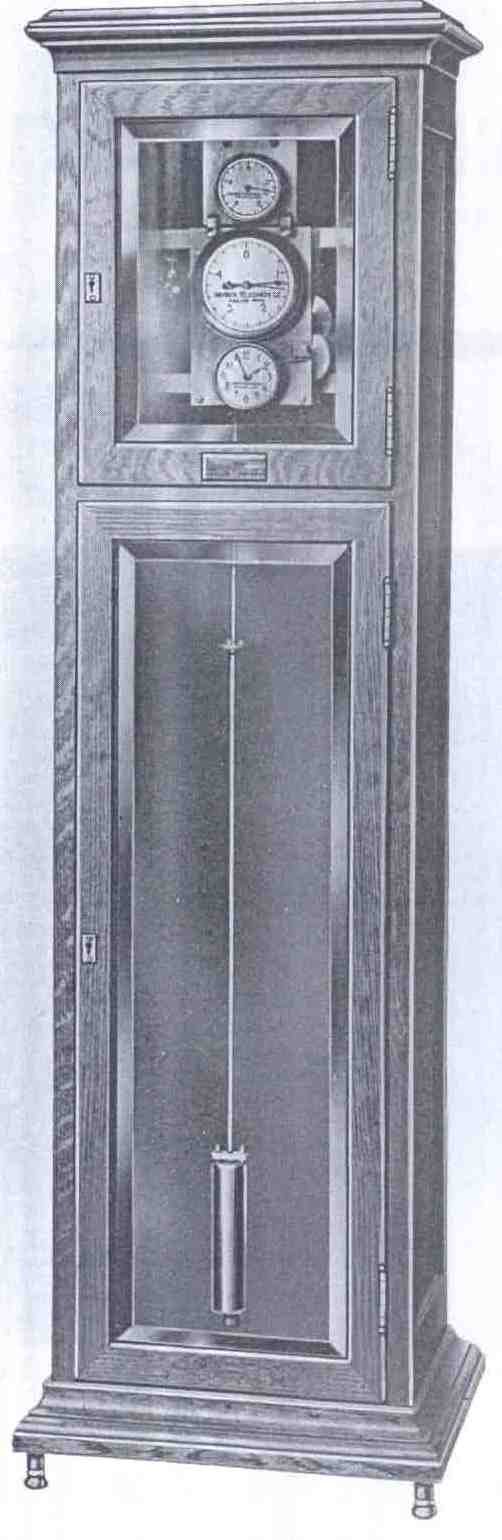

A la recherche du temps synchronisée

This post was written by James Nye

A number of us are fascinated by the whole concept and practice of synchronized public time. As well looking at the time transmission systems installed in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin and elsewhere in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, there are other intriguing facets to the world of time, its accuracy and its perception.

On something of an exotic riff, consider time in art. Dalí played with relativity in The Persistence of Memory and its softening watches, whilst Proust’s masterwork meticulously articulates the recovery through memory of a life observed at obsessively close detail – one can feel the clock ticking the author’s life away second by second as the narrative unfolds.

Back to the main hook, and significantly more prosaic, the clock, or broken watch, features regularly in detective fiction – think of Agatha Christie’s Clocks . Alibis often depend on time. I’ve collected detective fiction all my life, and recall the pleasure at finding Lord Peter Wimsey occupied a world full of synchronized clocks.

Witness the following from one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ finest books, Murder Must Advertise:

'The tea-party dwindled to its hour’s end, when Mr Pym, glancing at the Greenwich- controlled electric clock-face on the wall, bustled to the door, casting vague smiles at all and sundry as he went.'

Later in the same book, we learn of Wimsey’s difficulties at remaining in character, in disguise in an advertising agency… 'Nor, when the Greenwich-driven clocks had jerked on to half-past five, had he any world of reality to which to return…'

Sayers again touched on a number of public time themes in a later Wimsey story, Have His Carcase:

'In that intriguing mystery, the villain was at that moment committing a crime in Edinburgh, while constructing an ingenious alibi involving a steam-yacht, a wireless signal , five clocks and the change from summer to winter time.'

I’ll close with an appeal. If you know of similar appearances of time-signals, synchronized clocks and the like, in plays, novels, whatever, I’d love to hear about them!

A woman horological collector

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The AHS has recently paid attention to a number of Great Horological Collectors, with lectures that were later reported in the journal. All these lectures were about men.

That a woman could also assemble an important horological collection was demonstrated by the Austrian author Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830-1916). She had received practical training as a watchmaker and brought together a collection of 270 pocket watches dating 16th-19th century.

In 1917 it was purchased for the newly founded Wiener Uhrenmuseum, where the collection (sadly reduced to a mere 47 during World War II) is on display in a special room.

Her horological expertise and her love for her collection are reflected in her short novel Lotti die Uhrmacherin (Charlotte the Woman Watchmaker) of 1889.

Lotti is the daughter of a master watchmaker and is herself skilled in the craft. She inherits her father’s valuable collection of watches and refuses offers from other collectors, until her former fiancé gets in financial trouble. She relents and sells the collection, to be able to support him (anonymously).

Chapter 3 describes the collection in remarkable technical and historical detail, and names many makers – Le Roy, Breguet, Tompion and Mudge, to mention just a few.

Further reading: Eva-Maria Orosz, ‘“My watches make it hard for me to die”. Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach: the writer as watch collector’, pages 10-13 in Highlights from the Vienna Museum of Clocks and Watches (Vienna, 2011); I thank Fortunat Mueller-Maerki for bringing this essay to my attention. There is no English translation of Lotti die Uhrmacherin , but a freely downloadable edition with some English annotation is on-line here.

A multiplicity of times

This post was written by David Rooney

David Thompson’s post about Metamec ‘time savings’ clocks excited me, because I am interested in the wider cultural meanings around seemingly innocuous phrases such as ‘time is money’.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on the subject for the Science Museum’s ‘Ingenious’ website. It looked at the history of Benjamin Franklin’s 1748 phrase and how its meanings in different times and places varied.

Reading the article back, I have been reminded of a fascinating book by anthropologist Kevin Birth called Any Time is Trinidad Time (University Press of Florida, 1999).

Here’s what I wrote for the Science Museum:

'Trinidad, a Caribbean island between Venezuela and the USA, has a rich history of settlement and immigration. It is ethnically and culturally highly diverse, with residents of mainly Black and Indian origin mixing with Spanish, French and English colonial culture.

'Social anthropologist Kevin Birth spent time living there in 1989 in order to study cultures of timekeeping. Starting out with the often-used phrase "any time is Trinidad time", originally attributed to calypso singer Lord Kitchener, Birth explored the ways people come together with differing notions of timekeeping, and how conflicts are managed.

'He also looked at phrases like "time is money", "time management" and "budgeting time" and found that their use and meaning is highly complex and culture-specific. Generalisations were impossible.

'We all carry around with us a great variety of "personal times" – value systems linking time with activity – and we deploy them in highly complex ways according to culture, context and circumstances. Phrases like the Lord Kitchener lyric are complex devices used to oil the wheels of societies under time pressure.'

If you’re interested in how different societies use clocks, I can heartily recommend reading Birth’s book.

Money saving time

This post was written by David Thompson

There would be a knock at the door and my mother was busy. She would say 'that will be the insurance man – answer the door and give him this money and tell him the number is 16251'.

Many of us remember these numbers rather in the same way that anyone who did national service or served in the regular armed forces will surely remember their ID number.

In 1954 the Time Savings Clock Company Limited and Metamec of Dereham applied for a patent for a clock which would only go when coins were placed in a slot in the top of the case. Two florins weekly it says on the coin slot in the case top.

For people on insurance schemes with companies like the Co-operative in the 1950s, four shillings was quite a lot on money to put aside each week. The idea of the clock was to help people hold on to their money to pay the premium each week.

The system was invented by William Arthur Pitt and the patent was granted to the Time Savings Clock Company of Manchester (no.772,762). The mechanism consisted of a series of levers and wheels which arrested the going of the clock to which it was fitted until coins were inserted to release it and thus allow the clock to run.

These coins, after operating the levers would fall into the space at the bottom of the clock case, covered by a wooden panel which fitted over a stud and was closed by a wire and lead seal applied by the insurance man. When he called he would cut the seal, empty out the money and re-seal the back until his next visit – simple.

A full account of these clocks and many more everyday clocks can be found in Clifford Bird’s book – Metamec Clock Maker Dereham published in 2003 by the Antiquarian Horological Society.

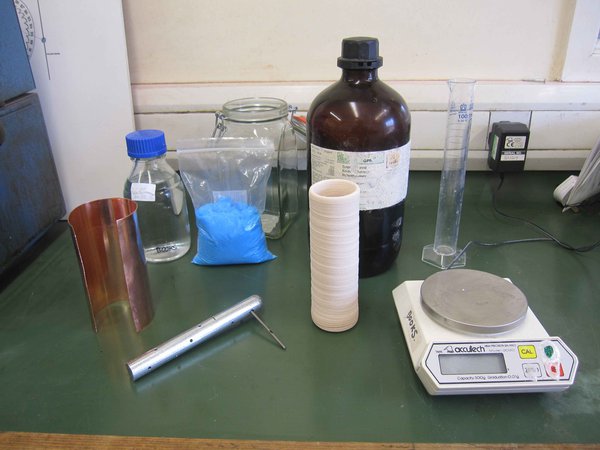

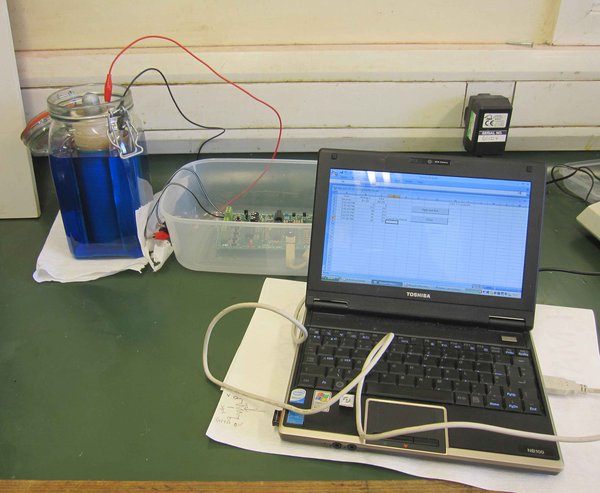

Making a 19th century battery

This article was written by Francoise Collanges

My MA project involves making a copy of elements of a mid-19th century electro-mechanical clock in order to see what the process could bring to conservation as a research tool.

One question was how the clock was originally powered and would it be possible to reproduce this today? Research revealed that power was supplied from a type of cell invented in 1836 by John Frederick Daniell, who gave it itsname.

The next questions were: how was the Daniell cell constructed, would it produce a constant enough current for reliable operation of the clock and would the voltage be similar to a contemporary cell? With the support and collaboration of two other West Dean Clocks Programme students, Jonathan Butt and Kenneth Cobb, materials were gathered.

In order to re-create a Daniell cell, the following was needed:

- A porous vase (kindly provided by Alison Sandeman, West Dean pottery tutor).

- A zinc anode (as typically still used for boat protection).

- A copper pipe.

- Sulphuric acid solution.

- Copper sulphate.

- A glass Kilner jar.

As soon as the sulphuric acid was added, the reaction started – the solution inside the vase started to fume and bubble and the cell produced current at its maximum voltage of about one volt. The cell worked constantly for five days (before the porous vase collapsed), with only minor intermittent drops in output (0.2 volts). During this time, the solution level within the vase dropped to almost half, copper crystals formed on the surface and thick crystals were visible at the bottom of the glass jar.

So we successfully made and tested a cell as it may have been made in 1836. Even with testing and research far from finished, it can already be said that:

- this clock was powered with a voltage even less than a modern 1.5 volt battery.

- it did not draw a huge amount of current from the cell, so the life length of the cell should have been of several days at least.

Furthermore, these results suggest that early electric clock systems were used in a different way from how we generally perceive them today.

The Clockmakers’ Charter

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

The Queen’s Jubilee this year is being celebrated at Royal Museums Greenwich with a terrific new exhibition, 'Royal River', which takes a fascinating and richly illustrated look at the royal history of the Thames. The city livery companies naturally play a central role in the story, and the curator, David Starkey, wanted to display a good example of an original royal charter from one of the companies.

The finest surviving of all the original royal charters just happens to be that of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, the charter of incorporation granted by King Charles I in 1631. The document itself was completed in 1634, Mr John Chappell being paid £4 for its 'flourishing and finishing'.

For the first time I have had the chance to look at it closely and have been reflecting on its significance.

It is in extraordinarily well-preserved condition and is a most beautiful and evocative thing. The obvious beauty of the document lies in its illumination and the elegant script, so carefully delineated on the vellum. But there is a second, less obvious, beauty within the charter, and one which I, as an historian and member of the company, personally find inspiring and reassuring.

Unlike many of the livery companies, which today have little practical connection to their founding craft, and have had many changes to their charter reflecting this, the Clockmakers Company still regulates its activities with reference to its 380 year old charter, which is still a relevant and legal constitution.

So carefully and intelligently worded was the charter that those parts which have become obsolete (such as the right of the Company’s officers to destroy poor quality work of a member) were always optional and can simply be allowed to pass unnoticed, but those parts relating to the administration of the company and its membership were obligatory, yet are as relevant today as they were then.

Today the majority of members of the Company’s governing body, The Court, are real horologists, and we can proudly say this is one company which has not lost connection with its roots.

Our pristine charter connects us straight back to our horological forefathers and it’s wonderful to reflect that today’s members of the Clockmakers Company are the natural and direct successors of Edward East, Thomas Tompion, Joseph Knibb and all the great names from the Golden Age of English clockmaking.

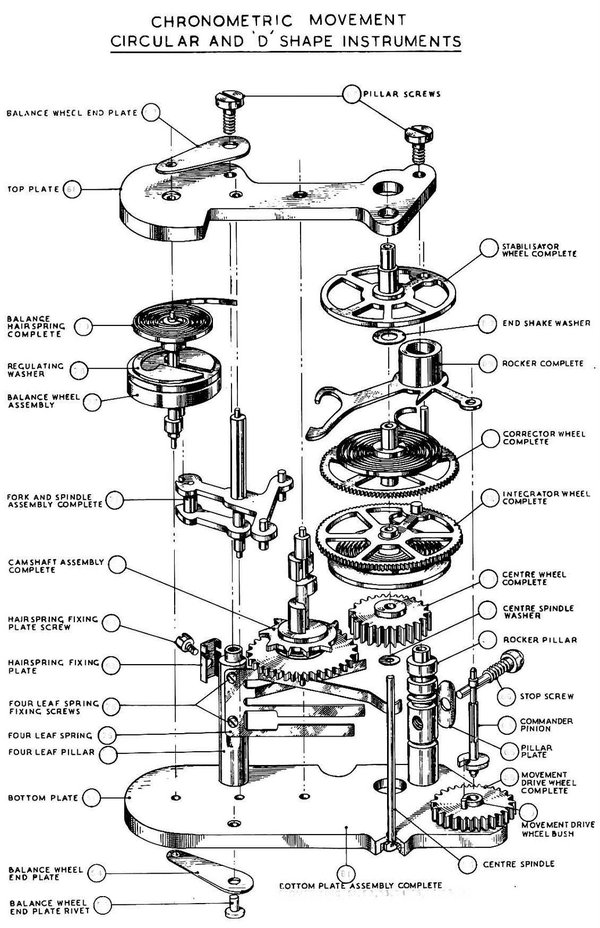

Whatever makes you tick!

This post was written by James Nye

I’m fascinated by machines that are largely clockwork, but which don’t show the time. A visit by West Dean students to The Clockworks meant digging some intriguing items out of the stores.

Consider the early electricity meter. Early on Jules Cauderay used an electrically maintained balance wheel as a timebase, and then occasionally engaged the dial work (recording units) depending on the load.

It took Herman Aron to come up with an accurate meter, using two pendulums, one for timing, the other influenced by the load to be measured. Integrating between the performance of the two trains allows the dials to show consumption.

‘Aha!’ you say, ‘How does the customer know the timebase is accurate?’ Simple – Aron arranged for the trains to swap roles regularly. A great place to see one working is Amberley Museum.

Henry Warren (synchronous motor man) used two trains to keep the power grid stable. When frequency stability was poor, he developed a device with a synchronous clock showing ‘grid time’ and a pendulum clock showing true time. By regulating turbine speed, accurate synchronous clocks for the home were possible.

Our UK ‘grid code’ specifies close tolerances over 24 hours, so your clock can be many seconds wrong, but on average, correct! At an AHS synchronous day, Michael Maltin fixed up a chart all round the room (like the Bayeux Tapestry!) showing a week’s (volatile) grid time versus GMT. You can see what the grid is doing right now here.

Another device that integrates two trains is the ‘chronometric’ speedometer, developed by Jaeger. This uses a balance wheel escapement, powered from a drive shaft as a timebase, allowing revolutions to be counted. A complex series of gears move the integrator and recording wheels back and forth, and the needle shows the last recorded speed. At least one manufacturer had to deal with customers who didn’t like the speedometer continuing to tick after they had come to a halt!

Lots of ticking – not much time!

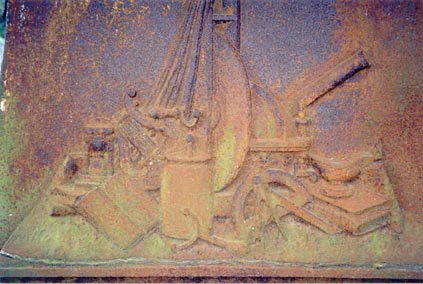

Scientific instruments on a watchcase

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Only a very small selection of the British Museum’s vast collection of watches is on display. Fortunately many more are described and illustrated in the museum’s online collection database, free for all to browse and explore. Visit www.britishmuseum.org > Research > Collection search, type in the word ‘watch’ and you get 6634 results!

Of course there are ways to limit your search. One watch that caught my attention was this gold cased, month-going cylinder watch by Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807), one of the most celebrated watchmakers in eighteenth century France. My special interest was the image on the back of the watchcase (Fig 1).

To quote the museum’s description: 'The design on the back – incorporating a universal equinoctial ring dial signed "OV BION A PA", an armillary sphere, a pair of dividers, a telescope, a microscope and a book – indicates that the watch was intended for a customer with scientific interests'. In fact, we discern one more instrument: an air-pump as used in physics experiments, as famously captured by Joseph Wright of Derby (Fig. 2).

As my professional background is in the history of scientific instruments, I find this watchcase of great interest. It reminds me of similar ‘group portraits’ of instruments that can occasionally be found on gravestones or funerary monuments in old cemeteries.

One example is this cast-iron funerary monument erected for a Dutch amateur of the sciences (Fig. 3). For details see this short article in Dutch; an English version appeared in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society Vol 69, June 2001, but is not available online.

If anyone knows other examples of scientific instruments depicted on a clock or a watch, please leave a comment, as I would love to know.

Second Rock from the Sun – Venus in a Sky of Diamonds

This post was written by Andrew King

The most eagerly awaited event of the astronomical calendar this year will pass us here on Earth on the 6th June. There are two Transits of Venus eight years apart but as this happens at intervals of more than 100 years we will have to wait until 2117 before we see it again.

The brilliant beacon of Venus signals the promise of the day to come and as the Evening Star, trails the Sun into the fall of night.

Venus the God of love and beauty and the name of the planet shrouded in what for centuries was believed to be watery clouds from which the light reflected from the Sun creates the famous glowing beacon apparently covering a romanticised tropical paradise. The truth is rather different.

Venus our closest planet at just 41,000,000 kilometres is a hell with toxic pressure nearly 100 times that on Earth combined with a surface temperature of 475 degrees centigrade. As for that luminous glowing envelope of cloud, it has proved to be an evil cocktail of carbon dioxide with a splash of sulphuric acid creating a ferocious green house effect.

For the astronomers Venus has always been of the greatest importance. As early as 1716 Edmond Halley [1656-1742], later to become Astronomer Royal, accurately predicted not only the next appearance of the Comet named after him but also the Transits of Venus of 1761 and 1769.

When all these events occurred it became a defining moment in the world of science as Halley’s calculations were based on the mathematics published by Isaac Newton in 'The Principia' of 1687. Graphic proof indeed of the Newtonian Revolution.

Halley believed, correctly, that the parameters gained from the Transits would enable the determination of the distance between the Earth and the Sun which in turn could lead to the estimation of the size of the Solar system – the Holy Grail of Astronomy.

This year the very best position to witness the Transit of Venus will be in Hawai’i where the Sun will be directly overhead. Here in Great Britain the sighting will not be as extensive as it was in 2004 but it is still an exciting prospect not to be missed.

Although the event starts at 11:10am BST on the 5th June , in G.B. it will not be visible until sunrise the following morning near the end of the Transit which lasts nearly 6 hours. At this time of year sunrise is early. In Edinburgh it will be at 3:30am BST, in London a little later at 3:45am and at Penzance later still at 4:15am.

Venus will appear as a black disc slowly traversing the burning hot face of the Sun always assuming that it is not obscured by cloud. Venus in Transit belies the regular morning and evening dazzling globe – Venus the Queen of Diamonds.

WARNING – Never look towards the Sun without the correct eye protection. It is essential to seek professional advice.

Meet Radcliffe

This article was written by Brittany Cox

Meet Radcliffe: he has real feet, wings, beak, body – the makings of a living bird, but without the squishy inner bits. They were traded over a hundred years ago for clockwork.

The scarlet tanager is an American songbird, which belongs to the cardinal family and is known for its red plumage and black tail and wings. Attempting to identify the old relative at my desk proved quite challenging.

Radcliffe, as I named him, was faded, dusty, and the light in his once bright eyes had dimmed with age. He no longer resembled his vibrant cousins. After sending the Audubon Society some images, I was thrilled to learn his true identity and imagined him singing in the lush canopies of South America.

What a strange thing, to outlive and out sing all others of his species, for as a mechanized bird he will go on singing for decades to come.

Repairing Radcliffe was no easy feat. Among the various faults in the mechanism, a section of the clockwork for commencing and ceasing the performance was missing and the bellows for voicing Radcliffe needed recovering. Zephyr, a fine parchment-like sheet of pressed goat intestine, was used to recover the bellows. The paper valves, allowing and restricting the internal air flow between the bellows chambers, were replaced with a brass and plasticine system, which I found to be the most fool-proof method.

After restoring the start/stop function to the mechanism, there was one other matter to sort out before Radcliffe was ready for his performance. He had lost his tail feathers over the years, so I made him a sort of toupée…

Using brass paper clips, I made a little ‘clip on’ tail that can be easily applied or removed without damaging his body.

There was a time when Radcliffe sang just for me; now he is singing for all of you.

A clock striking thirteen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Clocks strike the hours one to twelve and then start all over again. And yet, in a church tower near Manchester there is one that strikes thirteen, and has done so for over two centuries.

The idea of a clock striking thirteen times is a recurrent theme in literature.

Famously, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) begins: 'It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.' And in Philippa Pearce’s classic children’s book Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) a longcase clock striking thirteen inspires the boy to leave his bed and to step into the nineteenth century in a sun-lit garden.

The theme also comes up in history and in legends, and examples are quoted on Wikipedia. Some must perhaps be taken with a pinch of salt, but one that is most definitely true came up in a recent article in our journal.*

The authors live in Northwest England and are members of the AHS and meet fellow enthusiasts regularly in the Society’s Northern Section. In this article they discuss a clockmaker who worked in the region roughly in the age of Napoleon, and trace big turret clocks that can be linked to him, either as maker, installer or repairer.

A famous character in the history of the region was the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater (1736 –1803), known as the Canal Duke. His first canal was constructed to carry coal from the mines on his estates in Worsley to the markets in Manchester.

In 1789 he had a tower built to house what became known as the ‘Bridgewater Clock’. I now quote:

'There is a well known legend that the Duke witnessed his workers returning late after a lunch break. On asking them why they were late, the men complained that they could not hear the clock strike one above the noise of the yard. The Duke then promptly asked a local clockmaker to alter the clock so that it would strike thirteen at one o’clock. […] The clock remained in the tower at the Works Yard until the site was demolished in 1903.'

The clock eventually ended up in a London cellar, but was returned to Worsley in 1946 to be installed in St Mark’s Church, which then celebrated its centenary.

Unfortunately, the church is just a few metres from the M60 and a very busy intersection, so one has to strain to hear the clock above the road noise. But the evidence of the hands pointing to one o’clock and the thirteen strikes is there for all to see and hear, as can be witnessed in This short video.

* Steve and Darlah Thomas, ‘William Leigh of Newton-Le-Willows, Clockmaker 1763-1824: Part 1’, Antiquarian Horology , Vol 33 no 3 (March 2012), pages 311-334 .

With thanks to Steve and Darlah Thomas, Chester, for the information, photos and video.

Decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation

This post was written by David Rooney

I spend quite a lot of time thinking about leap seconds. They’re the extra seconds inserted into time at midnight on New Year’s Eve every few years.

Recently they’ve been hitting the news, as a proposal led by some American time scientists to abolish the leap second system has caused a bit of a furore.

OK, here’s the deal. For ever, we’ve measured time by the rotation of the Earth. One rotation equals one day. At least, that was the case until Louis Essen and Jack Parry developed the first practical atomic clock, in 1955 (you can see it at the Science Museum).

This technology, once developed and refined, became a more accurate timekeeper than the spinning Earth, so we moved to atomic clocks to measure time.

But we’re animals, and we’re therefore hard-wired to the temporal patterns of the Earth’s rotation – daylight and darkness, the seasons. So a system was designed to keep the new atomic timescale in step with the Earth.

That’s the leap second, and we’ve been recalibrating the atomic clocks with these occasional one-second corrections since 1972. The resulting timescale is called Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC, and it’s never more than a fraction of a second away from Greenwich Mean Time.

So the proposal by the American scientists to abolish the leap second system and let our civil timescale drift away from GMT has set a lot of people thinking about fundamental issues in the philosophy, technology and metrology of timekeeping.

My point? Recently I read about a colloquium held last October in Pennsylvania exploring the implications of redefining UTC as a purely atomic timescale – decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation.

You can read the papers and discussions here (click Preprints). This is truly fascinating stuff – measured, thoughtful and far-reaching, and the first substantial engagement I have read on the implications of this challenging proposal. Well worth a read if you’ve a spare second.

Horology in action

This post was written by David Thompson

Mechanical clocks turn up in the most unlikely situations.

When thinking of the Battle of Britain and the courage of the airman who flew Spitfires and Hurricane in defence of Britain in 1940, the humble clock does not immediately come to mind as playing a part in active service. However, selected aircraft in squadrons were fitted with a signalling device which allowed the controllers at strategic airfields to plot the position of fighter aircraft and so direct them to intercept approaching enemy aircraft.

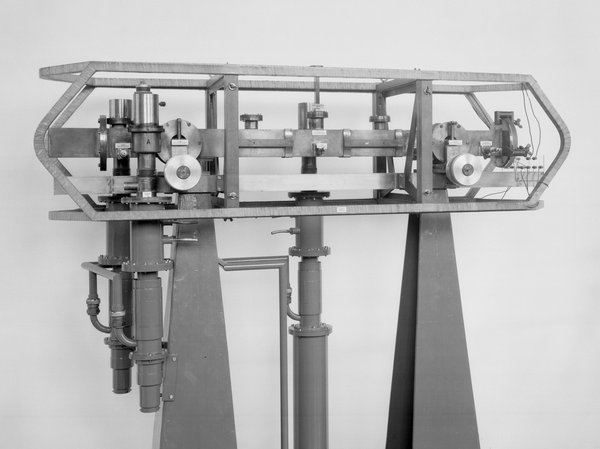

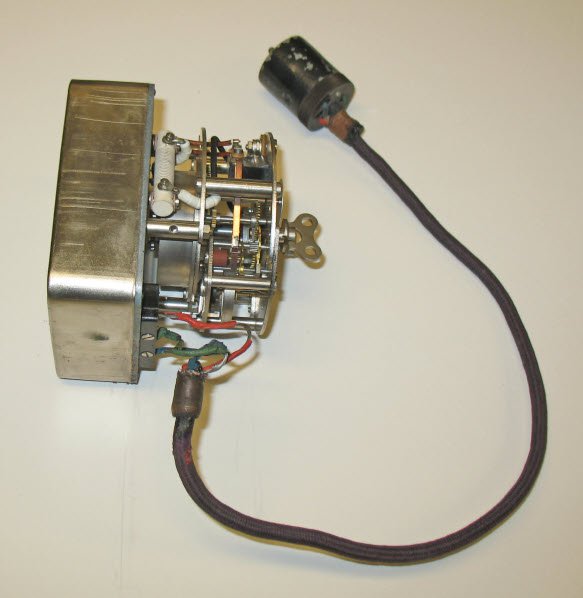

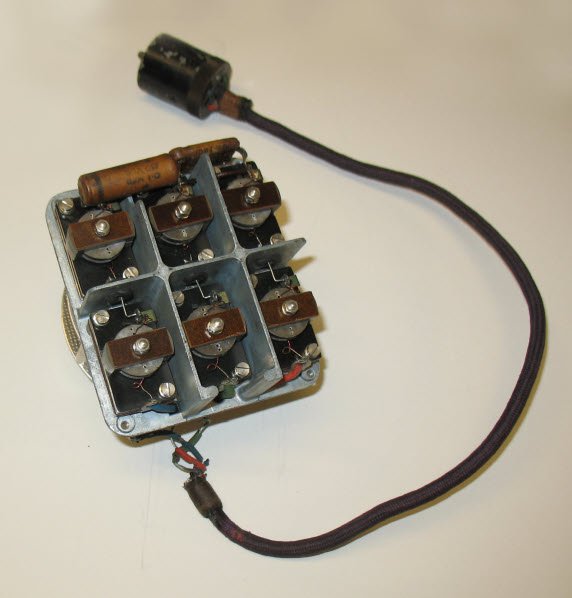

The system used by the Royal Air Force was commonly known as 'Pipsqueak'.

Fitted into the aeroplane behind the pilot’s seat was a Bakelite box containing a clockwork mechanism which would run for about five hours when fully wound. This was connected to an on-off switch located next to the pilot in the cockpit.

When switched on the aircraft radio would transmit a series of signals produced by electrical coils once per second for 14 seconds. The radio signal generated would then be received by the tracking station to enable the location of any particular group of aircraft to be located at any time. There is even a small heating coil inside to maintain the temperature to aid better timekeeping.

The system was normally used in two aircraft in the squadron. The clocks would be synchronised with the control tower and then when required the clock signals could be transmitted from the aircraft so that its location could be determined from the direction of the signal being received at a number of different receiving and transmitting stations. The information would then be transferred to the operation control centres so that aircraft could be directed to where they were needed to intercept the enemy.

Link to source of Spitfire image used above.

A book sale to remember

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Many of us who are captivated by the history of timekeeping have an equal interest in the historical literature on the subject; in fact, such is the fascination with antiquarian horology, that quite a few of us have more books than clocks and watches!

For these horological bibliophiles (don’t try saying that with your mouth full!), ‘the sale of the century’ took place last month (on 22nd February) when Dreweatts of Donnington sold the working library of the distinguished antiquarian horologist, Charles Allix.

Charles, who is now enjoying a well-earned retirement, amassed a very fine collection of books and ephemera, and with subjects ranging from turret clocks to watches, there was something for everyone.

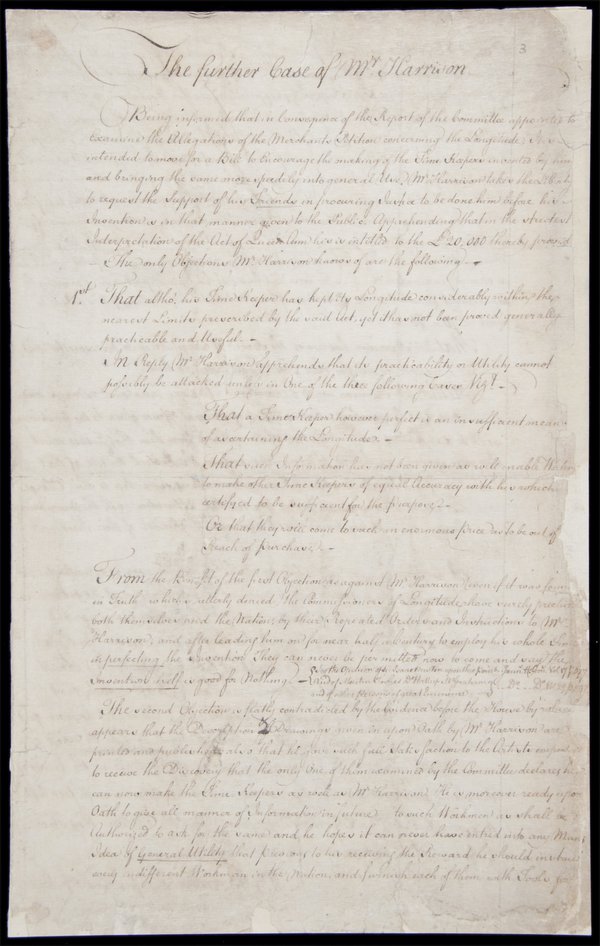

Undoubtedly the stars of the show were a small group of manuscripts which had belonged to the great John Harrison (1693-1776) and it was predictably these lots which brought the highest bids.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers hold the largest body of original Harrison manuscript material, and the Company were keen to add these, which were some of the very last Harrison-related documents out of safe captivity in museum collections.

The lots were hotly contested – some of the prices were a long way above upper estimates – and the horological world was reminded again of the enduring interest and importance of the Harrison story.

In the event, most were acquired by the Company (Charles Frodsham’s kindly doing the bidding on their behalf), and they are now safely secured for the future and available for research.

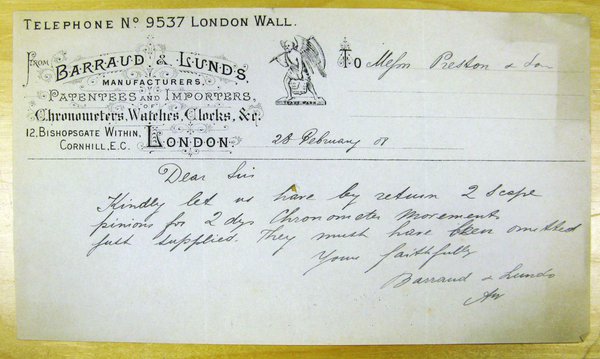

My own organisation, recently re-named Royal Museums Greenwich (after the Borough was granted Royal status) was also successful in acquiring some fascinating correspondence from the firm of Preston’s of Prescot, one of the most significant English manufacturers of rough movements for marine chronometers.

The extraordinary detail informing the day-to-day processes involved in making and supplying these movements to the finishing trade, will greatly enhance the research currently being carried out on the museum’s collection of marine chronometers.

This research is due to be published in a large and definitive catalogue The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich , due out in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the 300th anniversary of the famous Act of Parliament offering huge prizes for solutions to the problem of finding longitude at sea.