The AHS Blog

A telescope by Henry Hindley

This post was written by Tim Hughes

The work of Henry Hindley of York was researched by Rodney Law and published in Antiquarian Horology (1971/2). The article describes two equatorially mounted telescopes signed Hindley.

The first of the two telescopes forms part of the collection of the Burton Constable Foundation, East Yorkshire, and the later instrument is now in the collection of the Science Museum London.

In recent months, the earlier instrument (circa 1740) has been through a process of conservation cleaning and close study by Tim Hughes of West Dean College.

The instrument is regarded as of significance and is known to have been purchased by William Constable for use in the eighteenth century observations of the Transit of Venus. The telescope mount bears much resemblance to that by James Short published in Philosophical Transactions in 1760, having meridional, equatorial and declination circles over a primary setting circle.

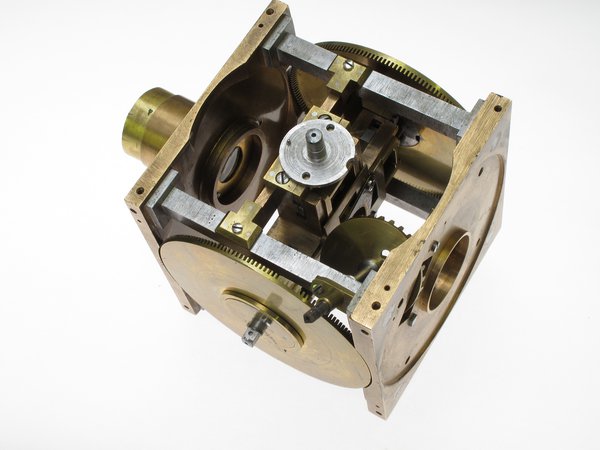

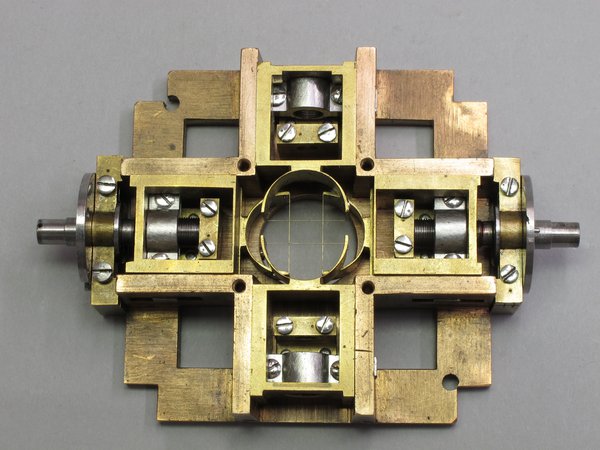

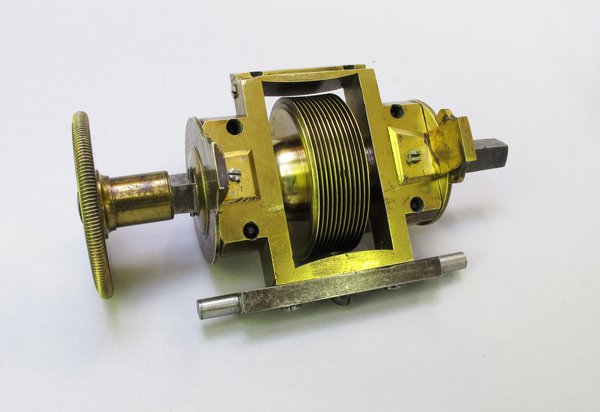

Interestingly, Hindley’s telescope mount is a combination of sound mechanical clockmaking practice – including the very precise and beautifully made worm gearing – and surprisingly unstable telescope mount which raises questions about the development process and Hindley’s involvement with the various stages of manufacture.

The instrument is signed on the micrometer box only, which is in itself a piece of clockmaking genius. Within the box are fitted four reticule frames, connected by intermeshing contrate wheels operated by a setting knob. The reticules form an adjustable square frame within the field of vision allowing angular measurement of the size or distance between objects.

Work on cleaning and recording the instrument is almost completed and has been assisted by Charles Frodsham and Company Limited who have kindly carried out measurement of the gearing of the equatorial circle and its driving worm.

Once re-assembled, we intend to carry out field tests with the help of a professional surveyor in order to better understand the calibration and range of the instrument which may further inform its purpose and limitations. A paper giving a technical description of the construction of the instrument to appear in AH in due course!

Enicar will do

This post was written by James Nye

Collectors of Enicar watches may be intrigued by a story I recently uncovered.

The life of this popular Swiss brand (1913–1988) took in two world wars and the quartz revolution of late 1960s. The name Enicar derives simply from reversing the family name of the owners, Ariste and Emma Racine. Starting with movements from Schild, the couple expanded Enicar operations with a large manufactory in Lengnau (in Biel) after the Great War. The history of the firm is summarised here.

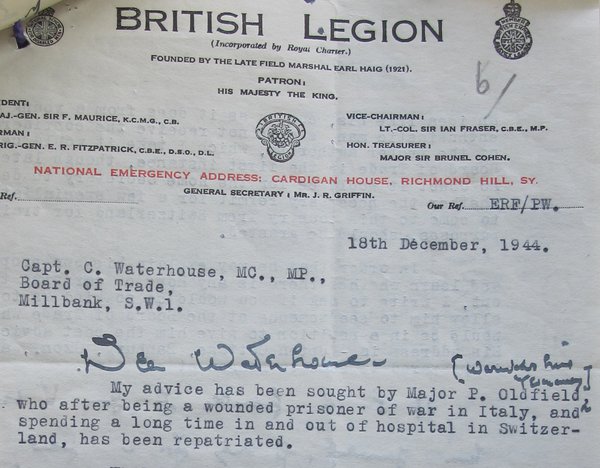

Ariste (junior) took over in 1938, and had to steer a cautious path through the Second World War. Some firms supplied both German and Allied clients, but we have some insight into Ariste’s sympathies through the extraordinary story of Major P. Oldfield, a wounded prisoner of war in Italy, who escaped to Switzerland, where he was in and out of hospital.

As part of his convalescence, he trained in simple clock assembly, developing an ambitious business plan with Ariste. After repatriation in 1944 to the UK, Oldfield helped his partner travel to London to seek permission for an alarm clock factory in the UK.

Racine had tried the scheme before, in 1939–1940, with the Clerkenwell firm of Robert Pringle & Co, but Edwin Pringle died in 1942, and in 1944 Racine used Oldfield as a new conduit to the Board of Trade to revive the idea, with a view to importing machinery from Switzerland, at first to assemble imported parts, but ultimately to manufacture alarms.

The British government was keen on schemes that could employ wounded ex-serviceman, and Oldfield was the walking advertisement. From alarms, Enicar UK would graduate to watch production.

The scheme did not progress, probably owing to resistance from the UK trade, perhaps hostile to competition from a Swiss national proposing to set up production without government subsidy. But the project interested the British government for some time in 1944–1945, and the file (BT 64/3661) at the National Archives would prove rewarding to the serious Enicar enthusiast. By all means contact me for help.

Horological horrors

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Browsing the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library I found a collection of cigarette cards, issued by tobacco manufacturers as an added incentive to buy their product.

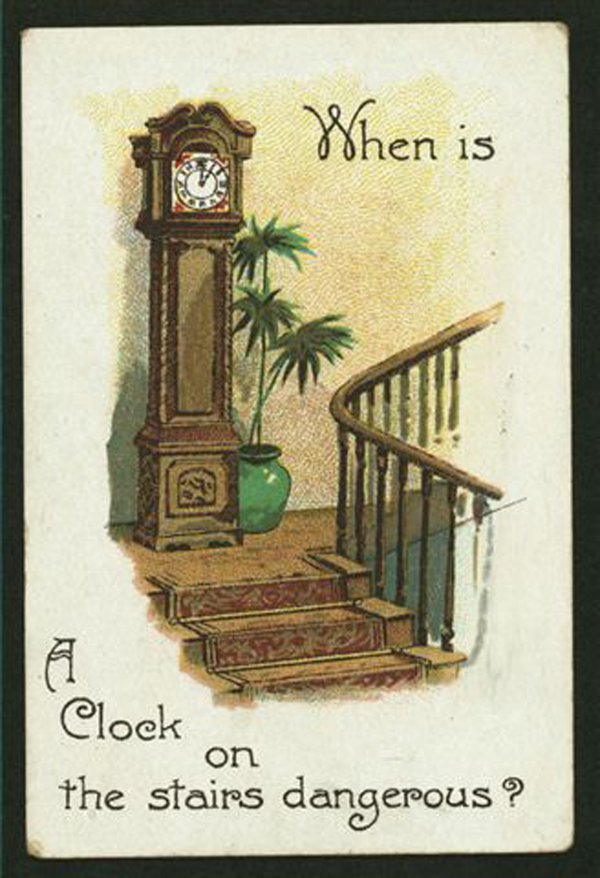

On one of these cards we see a drawing of a longcase clock (the tall, standing type also known as grandfather clock) on a landing, with a riddle: ‘When is a clock on the stairs dangerous?’ The answer is printed on the back of the card: ‘When it runs down and strikes one’.

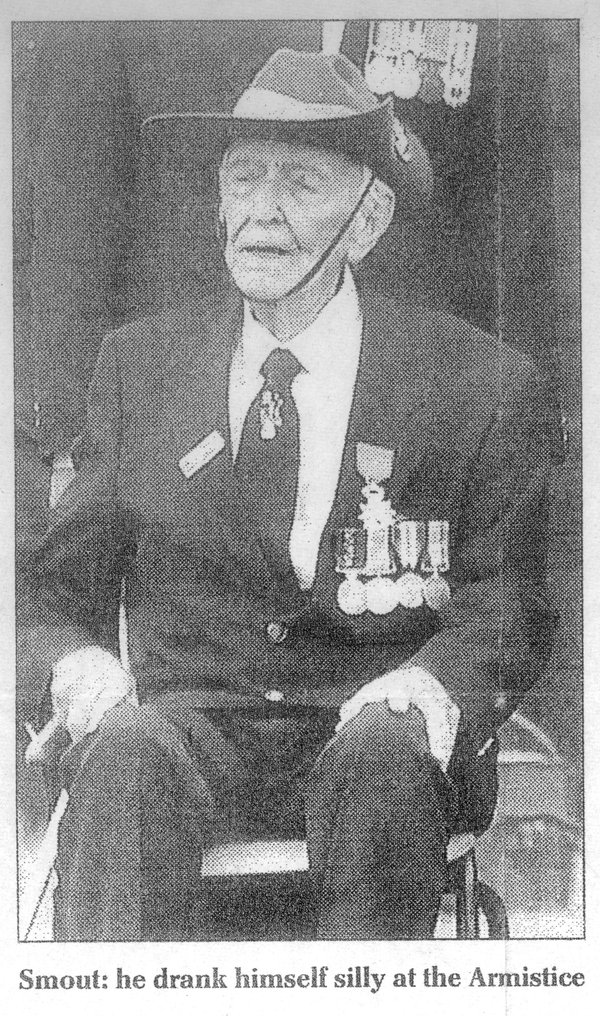

Jokes aside, longcase clocks can be dangerous, as one of the last Australian survivors of the Great War found out. When he died aged 106, the Daily Telegraph obituary had this lurid detail: two years earlier he had become trapped under his own grandfather clock when pulling up the weights. What an unexpected assailant for a veteran soldier! An AHS member sent me the clipping, after a neighbour of his had had the same misfortune. The lesson: make sure your longcase clock is firmly fixed to the wall.

Of course, there may be situations where you simply don’t have time to do that.

In his latest monthly column ‘Diary of a clock repairer’ in Clocks Magazine, Robert Loomes writes how he delivered a restored grandfather clock to a house in the countryside. Just as he finished setting it up, a squirrel ran into his trouser leg (you couldn’t make it up). Quite understandably, he stumbled and fell, and the assembled clock was dashed to pieces.

In September 2010, an AHS member in the Canterbury region in New Zealand wrote to me: ‘It was a sad day for unsecured longcases last Saturday. There was a major earthquake in Christchurch and at least two friends who had yet to screw new acquisitions to the wall had them tossed across the room and smashed.’

At my request, he wrote a short piece about it for the journal, and supplied a photo of one of the damaged clocks. Sadly, five months later a second, more destructive earthquake hit Canterbury, causing massive destruction and killing 185 people. In that light, it would have been insensitive to print the piece about damaged clocks. Fortunately I could just withdraw it before the journal went to the printer.

Happy St Lubbock’s Day

This post was written by David Rooney

If you live in the UK or the Republic of Ireland, I hope you enjoyed the bank holiday earlier this week. Perhaps you went with family or friends to one of the many great museums with horology collections.

For bank holidays we can thank the remarkable Victorian polymath, John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury), who was the subject of a fascinating Royal Society conference I attended recently.

Lubbock is usually associated with the preservation of Britain’s ancient monuments such as Avebury. In 1882 his landmark Ancient Monuments Act was passed. But this was not nostalgia – Lubbock believed the relics of the past helped us understand our own progress, and he was about as modern as you could get in the late nineteenth century.

It was in electricity that Lubbock truly blazed a trail, a story I’ve recently been researching. Many in the AHS are interested in electrical timekeeping, a subject with more than a century and a half of history, and the place of the electrical industries in this story is crucial.

In 1882, the same year that he guided his ancient monuments bill to completion, Lubbock also sponsored the Electric Lighting Bill, and became a director of Thomas Edison’s offshoot company formed to bring electric lighting to Britain. His firm financed and founded the world’s first public electric power station, on Holborn Viaduct, and the following year he steered through the merger of Edison and Swan, Britain’s two pioneering electrical companies.

Lubbock once gave a lecture praising the work of William Cooke, Charles Wheatstone, Alexander Bain and Louis-Francois-Clement Breguet, amongst others. Electricians, yes, but horologists too.

So if, on your bank holiday museum trip, you saw clocks by any of the electrical pioneers, it is worth thinking of the role John Lubbock played in creating the modern electrical world – and in creating a world that values the relics of the past. And you can also thank him for giving you the day off.

Japanese time

This post was written by David Thompson

From the first appearance of the clock in Japan, when the Spanish Jesuit priest, St Francis Xavier, arrived with gifts for the Emperor, including at least one clock, in 1551, the story of mechanical timekeeping in that country has been an intriguing one, and one which lasted until the end of the Edo dynasty in 1873.

From 1612, when the Europeans were expelled from Japan and the country was closed to outside influences, the Japanese clockmakers were on their own for over 250 years. What they produced in terms of clocks was indeed ingenious.

First of all, how was time measured in Japan in that period? Take the hours of darkness and divide those up into six equal parts. Then take the hours of daylight and also divide those up into six equal parts and there you have it. Clearly if the day is divided in this way, the length of the daylight periods and those of darkness will vary throughout the year except at the equinoxes when all the hours will be equal and equivalent to two hours of European time.

Unfortunately, mechanical clocks like to keep equal unchanging hours as best they can. So, what did the Japanese clockmakers do in circumstances where they had no access to what was going on in far distant Europe at the time?

Three quite effective methods were devised to get round the problem:

- to have two separate oscillators in the form of weighted swinging bars known as foliots with adjustable weights to change the rate of the clock.

- to have moveable markers either on a round dial or on a flat bar, depending on the type of clock.

- to have a series of plates, usually fourteen, which would be changed periodically depending on the time of year.

In all three types the time indication would have to be adjusted twice per month.

When it came to style, there were basically three types of clock in Japan:

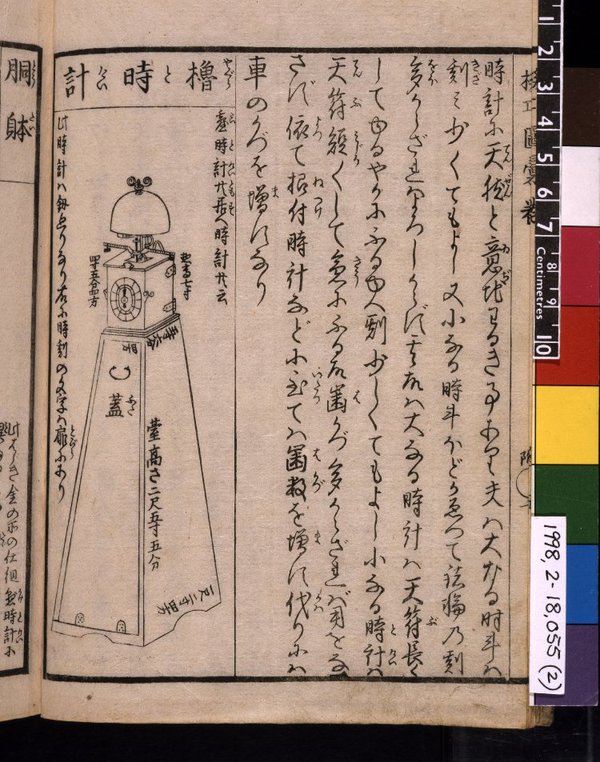

- the stand or lantern clock, weight-driven and either mounted on the wall or placed on a stand.

- the table clock, designed to be placed on tables or on a suitable place in an alcove.

- the pillar clock, specifically made to hang on the thin wooden pillars which made up the framework of the inner paper wall of the house.

In the early period, the oscillating foliot was used as the timekeeping element, a single one in the earliest clocks and a double in the later, more sophisticated examples. As the technology progressed, pendulums or oscillating spring balance wheels were used – a larger form of the device found in mechanical watches.

Such clocks were only owned by the wealthy and were perhaps more used as status symbols than they were to tell the time and organise the household.