The AHS Blog

Home time

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

As next year’s AHS conference will be shaped by the theme ‘Military Time’, it seems appropriate that this post should follow the military theme and by chance, as with David Read’s recent post, it includes a radio.

There are two HS.4 navigational watches in the National Maritime Museum collection, both retailed by the firm H. Golay and Sons, which were used by the Fleet Air Arm in Fairey Swordfish aircraft during WWII.

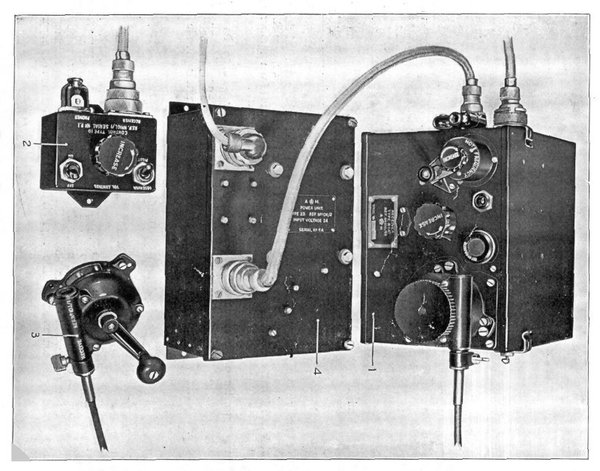

We learn from the 1941/1942 Admiralty Manual of Navigation that these watches were known as beacon watches and that they were only to be used in aircraft fitted with an R1147 radio receiver.

The carriers were equipped with a revolving beacon that continuously transmitted second pulses, making a full rotation once per minute. The crucial feature of this system was that the beacon emitted a different sounding signal when it was pointing due north. Prior to launch (these planes were catapulted into the air) the observer would tune the radio receiver to the beacon and set the bezel of the watch so that zero on the outer scale and the tip of the second hand align precisely at the time of the northern signal.

When returning to the carrier, the observer on board the aircraft would turn on the radio and listen to the beacon’s signal. The strongest reception would be experienced when the beacon was pointing directly at the aircraft and using the watch, the aircraft’s position relative to its carrier could be found and the pilot given the course to take.

If we take the watch shown above, for example, as indicating the moment of the signal’s maximum intensity, the aircraft’s position would be approximately SSW of the carrier. The primary benefit was that these slow aircraft could home in on their carrier from up to 100 miles away without sending out radio signals that may betray their position to the enemy.

This ingenious horological adaptation helped to save lives and is just one example of innovation necessitated by war that could be explored at next year’s conference.

If you feel that you can contribute a talk that would fit ‘Military Time’ theme, you are invited to contact the AGM lecture coordinator, Rory McEvoy, Curator of Horology, Royal Observatory Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SE10 9NF, e-mail: RmcEvoy@rmg.co.uk. Papers could explore technical horological development as well the wider implications for both civil and military timekeeping. Please note that the theme is not limited to the First World War, and that the military of course includes the ground, sea and air forces.

When is a wrist watch not a watch?

This post was written by David Read

In February 2013 it was leaked that Apple was experimenting with an iWatch. However, six months later and at the time of writing this blog there is still no news from Apple and the technical press is now guessing that the project has hit battery problems.

If only Dick Tracy, the famous cartoon sleuth, was still around to find out what the bad guys are up to and get at the iWatch facts. Tracy had sported a remarkable watch on his wrist since 1946 and now, 67 years later, Time Magazine described that watch as 'the most indestructible meme in tech journalism'.

For decades now, it has been nearly impossible to write about communications technology combined with a wristwatch without invoking the plainclothes cop with a special watch on his wrist who first appeared in 1931, even though the days when one could follow Dick Tracy’s adventures in a daily newspaper have long gone.

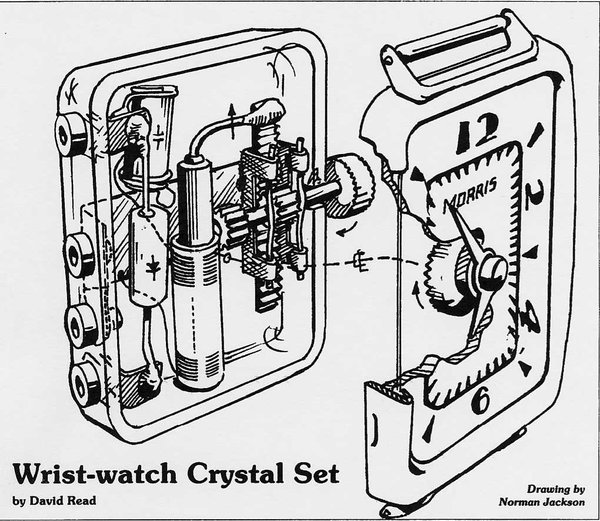

Popular science fiction is always years ahead of the technologies that turn dreams into reality. However developments in solid state electronics had, by the 1940s, enabled the large galena and cat’s whisker detector of the crystal set to be produced as a tiny point-contact diode and placed inside a wrist watch case as in the Morris watch shown here.

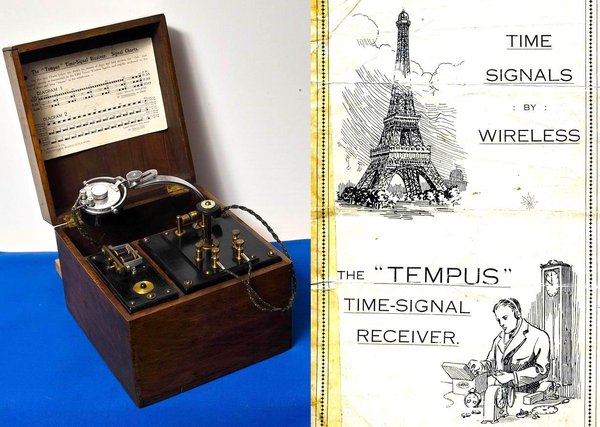

But is this a watch? No, it’s a crystal radio. However, horology and radio have a long shared history involving frequency and time. This clandestine wristwatch radio can receive time signals in exactly the same way as mariners and watchmakers did from 1912 in order to check their chronometers, clocks and watches against the timecode transmitted from the Eiffel Tower. My image of the Tempus crystal radio and instructions sets the scene.

The illustration of the Morris watch shows a standard-sized watch case made of chrome-plated steel. The dial, signed Morris, is in typical 1940s style. The standard of manufacture is high and the disguise on the wrist is perfect. The case back is made of moulded Perspex to provide an insulated chassis on which the circuit can be built without special measures to insulate the components, aerial, earphone sockets and associated wiring.

The winding button is actually a dial knob and connects to a rack-and-pinion control of tuning in which an iron-dust core is moved within the aerial coil and tunes the required frequency by altering the coil’s inductance. This assembly is connected to the earthy end of the coil and also to the metal case thus providing a body earth to stabilize the circuit whilst tuning. A tiny sealed point-contact crystal detector is enclosed in an evacuated glass tube and a capacitor across the coil completes the circuit.

A second pinion on the winding stem connects with a crown wheel on which the hands are mounted. This alters the position of the hands on the face of the watch and provides a scale against which a station can be memorized or noted. Using the wrist watch crystal set in conjunction with a deaf aid as an amplifier would have allowed the use of a short aerial such a bedstead and completed the disguised operation.

The drawing was made for me in the 1980s by my late dear friend Norman Jackson, an outstanding engineer and artist whose illustrations always showed at a glance how things work; something that photographs can never match.

It is interesting to speculate why such a radio was made and I have never seen another. However, the Morris watch cannot be unique because it is a professionally designed object requiring bespoke production tooling and Perspex moulding facilities. The public market for such clandestine receivers would have been tiny and with no chance of recovering the costs involved. Without a consumer market for this item it would seem possible that it was funded by a government agency and the headline news today shows that such agencies are still active in the ancient arts of listening, spying, and gathering information.

And another thing – yes it does work!

Clocks and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

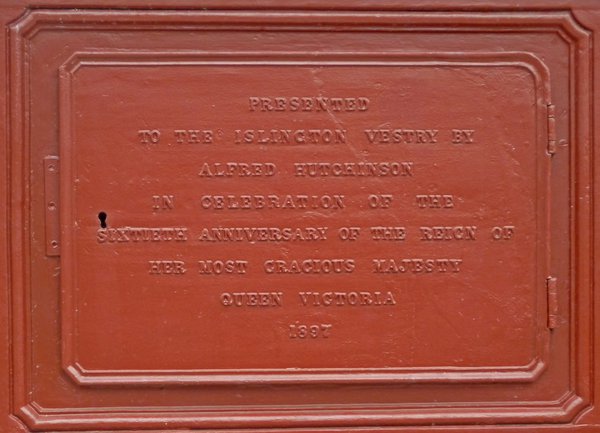

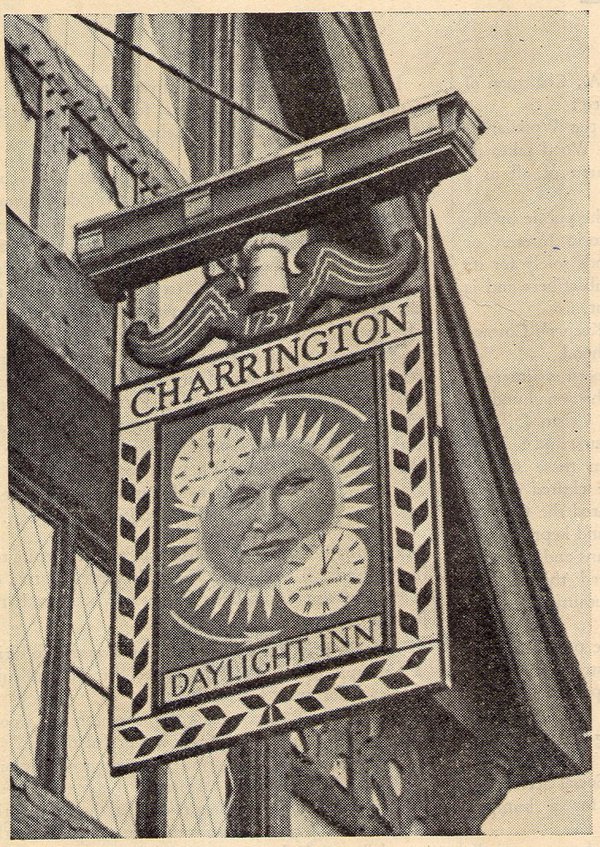

Cycling through north London I like to pass by the Jubilee Clocktower at Highbury, Islington, near the Arsenal football stadium. It was erected in 1897, sixty years after Queen Victoria came on the throne. And in the March 2011 issue of Antiquarian Horology we published a photo of a jubilee clocktower at East Harptree, Somerset, taken during one of the regional excursions of the AHS Turret Clock Group.

These are just two of what must have been dozens, perhaps hundreds, such clocktowers that bear witness to the commemorative zeal of the late Victorians. In February 1897, a specialist firm issued the following circular letter intended to generate new orders:

'We desire to draw the attention of the Nobility, Clergy, Gentry and others, who are contemplating the erection of Church and Turret Clocks in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, to our unrivalled facilities for manufacturing all kinds of clocks at the lowest possible prizes consistent with good workmanship and material, and to all requiring the same we would be glad to furnish estimates and information free of charge.'

Quoted from Michael S. Potts, Potts of Leeds. Five Generations of Clockmakers (Mayfield Book 2006), p. 133.

Many orders came in. The smallest clock tower that Potts installed in 1897 stands, fourteen feet high, on the town square of Much Wenlock, Shropshire.

Wikipedia has a list of jubilee clocktowers which also includes examples erected ten years earlier for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, like the one on the seafront at Weymouth, Dorset. They were also built in outlying parts of the British Empire. The Victoria Clocktower in Georgetown, Malaysia is still a well-loved landmark. It is sixty feet tall, one foot for each year of Victoria’s reign.

It would be great to have a proper study of these late nineteenth-century jubilee clocks and clocktowers, with a gazetteer telling us where they are, and of course who supplied the clocks. Something for a website, a book, or perhaps an article in Antiquarian Horology?

Walking the ‘Willett Way’

This post was written by David Rooney

Every spring, when we put our clocks and watches forward for British Summer Time, we do so with a hollow laugh. March weather is rarely summery! But last month many in the UK have seen prolonged sunshine, and in London we’ve had a heat wave. Summer arrived at last.

If you like walking in sunny weather, and if you’re in London, you can combine a walk with finding out more about British Summer Time. It takes in Petts Wood and Chislehurst, home of William Willett, the schemes creator, and it’s easily accessible by public transport.

You can view the walk instructions online or print them off. But I must warn you that it’s a while since I prepared this trail, and things might have changed. Do take care and, if in doubt, follow your common sense, not my instructions! One thing that changed since I wrote the walk is the refurbishment of Willett’s grave, now looking superb.

It fascinates me that twice a year, every year, quarter of the population of the Earth changes its clocks and watches for summer time. That is a real, physical, close engagement between billions of people and billions of timekeepers each year across the globe—all because a Victorian British house-builder and moralist thought we should get up earlier in summer.

What this shows is the sheer power of clocks and watches to change and order human behaviour—or rather, the inventive ability of people to use time to control other people. We can see it all over the place when we know what to look for. Time is a political tool.

And that is one reason why you should join the AHS. Knowledge is power, and the more we understand timekeeping, the more we can understand the control that people exert on our lives using it. PS I’ve recently joined Twitter. If you’ve nothing better to do, you can follow me @rooneyvision.