The AHS Blog

Clock world full of cranks?

This post was written by James Nye

Things turn up. Back in 2006, when David Rooney and I were researching the Standard Time Company (STC), we planned a lecture at the Guildhall library.

The only surviving early clock we knew of had spent its life at the Royal Observatory—but out of the blue, days before the event, a Lund-synchronised dial clock turned up.

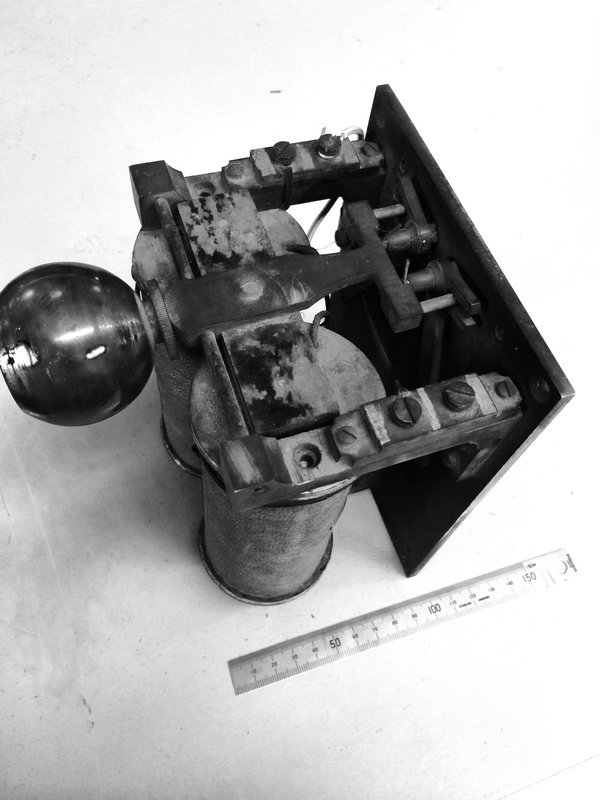

In the following eight years, that was it—nothing else—and then suddenly, through the kind agency of Keith Scobie-Youngs, The Clockworks acquired a wonderful addition a few weeks ago, in the form of an outsized fusée gallery movement, fitted with a massive Lund synchroniser.

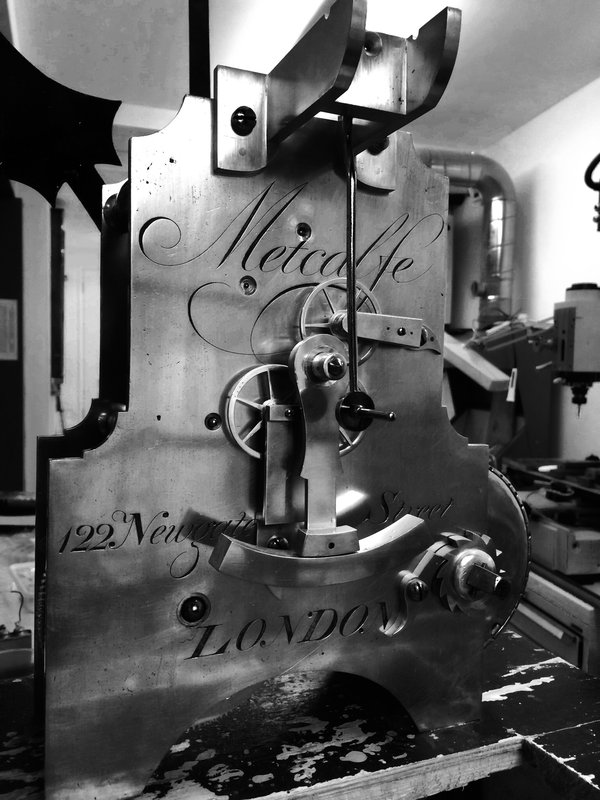

The movement is by Thwaites, from the early nineteenth century, and signed elaborately by Metcalfe of 122 Newgate Street, London.

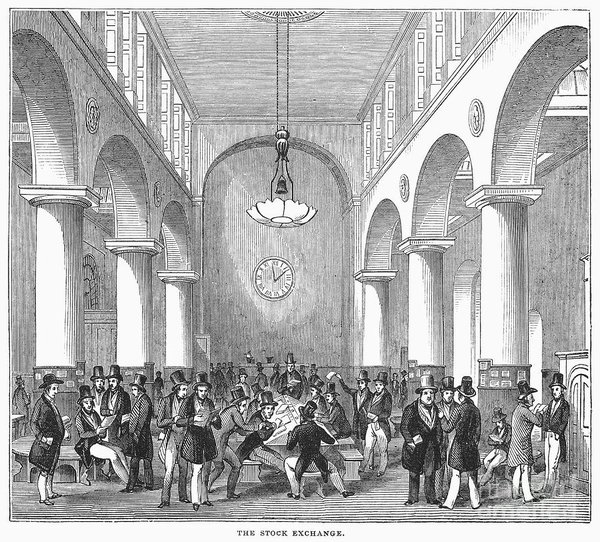

When STC went public in 1886, it listed its clients in the prospectus, and the very institution on which it was being floated appeared second in the list.

The accurate timing of bargains made by the jobbers on the London Stock Exchange was an important matter, and ‘the House’ was an early adopter of the new technology that provided hourly synchronisation of its clocks.

Remarkably, our new addition was one of probably several STC-synchronised clocks that populated ’Change, where it seems to have served for some time.

Each hour, a signal would travel from STC’s offices on Queen Victoria Street around a series of looped networks, energising the coils of the synchronisers. These were the ‘set-top boxes’ of their day, added perhaps many decades after a clock was first made—as was clearly the case with this clock.

The Stock Exchange synchroniser is particularly large, operating two small fingers that project through the dial, to correct the minute hand each hour. The long use of the device is evidenced by the deeply indented witness marks in the tab on the back of the hand, caught by the synchroniser.

.

Overall the movement seems rather outsized for the scale of the dial it ended up supporting—the large counterweight is much more than a match for the 15-inch minute hand.

Sometimes, it’s very hard for us to trace the environs in which our clocks spent their time—and to deduce whose lives they counted out. Thankfully in the case of this remarkable STC clock, there’s an old crank that can tell us a story or two.

Stopping the clock after death

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In a previous post I included an opera scene, in which a woman mentions (sings!) that at times she stops all the clocks in her house. She dreads getting old and wants time to stand still.

One reader told me this reminded him of a poem by W.A. Auden which begins:

'Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

'Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

'Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

'Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.'

But here the motive for stopping the clocks is different. Someone has died, and stopping the clocks in the house of the deceased, silencing them, is an old tradition, similar to closing the blinds or curtains and covering the mirrors. The clock would be set going again after the funeral.

Some people believe stopping the clock was to mark the exact time the loved one had died. The subject was discussed here by members of the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in America.

The French film Jean de Florette, set in the Provence between the wars, contains such a clock-stopping scene. The film is made after a novel by Marcel Pagnol, from which the following quotes are taken.

Jean, an outsider, inherits a house with surrounding land and hopes to make a living there. But two locals, who covet his land, secretly block a source, cutting off his vital water supply.

In despair, Jean uses dynamite to create a well, but he dies as a result of the explosion (chapter 37). The doctor, taking his pulse, 'listened for a long time in a profound silence emphasized by the ticking of the grandfather clock', but the man had died.

Then one of the two devious locals, who was in the room, 'crossed himself, walked around the funeral table on tiptoe, and stopped the pendulum of the grandfather clock with the tip of his finger'.

He then tells his comrade in arms 'Papet, I have just stopped the grandfather clock in Monsieur Jean’s house' – a way of saying: he is dead.

The three stills reproduced here are from that scene, which you can see in this short clip.

The clock is a typical Comtoise grandfather clock with a big flower pendulum.

100,000 more free images

This post was written by David Rooney

When I got an email from the Wellcome Trust which began, ‘we have some very important news to announce’, it certainly got my attention.

And they were right: it is very important news indeed, and I’m delighted to share it.

In my last post I talked about the recent release of a million images by the British Library. Already I’ve heard from colleagues and friends who say they have found new evidence amidst its vast collections that is crucial to support their research.

The news from the Wellcome Trust is the same. As of January this year:

'All historical images that are out of copyright and held by Wellcome Images are being made freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This means that they can be used and manipulated freely, for commercial or personal purposes, so long as the original source is acknowledged.'

You can download high-resolution files directly from their website. There are 100,000 images dating from as early as 1000 BCE. You can even get advice directly from Wellcome’s team of researchers, should you be having trouble finding what you need.

Like many in the AHS, I’m interested not only in clocks and watches themselves, but how horological machinery gets embedded in other technologies. So I searched for ‘clockwork’ and, rather than showing you the clockwork trephine (not safe for suppertime), here’s a clockwork picture of an itinerant dentist performing an extraction in the early 19th century. Ouch.

Whether you’re into automata like this, or medical technology, or astrology or philosophy or geology or anything else related to stories of time and its material culture, you’re sure to find something here to delight.

As I said last time, image banks such as this are invaluable treasure troves of historical evidence for researchers, whatever your subject. Serendipitous browsing leads to new leads and new ideas.

Huge thanks to Catherine Draycott and others at the Wellcome Trust (as well as the British Library) for making such a bold and generous decision to open this to everyone.

The Battle of the Three Emperors – or the Battle of the Three Dates

This post was written by David Thompson

I was recently reading Dušan Uhlír’s book The Battle of the Three Emperors and I came across an intriguing fact about the battle of Austerlitz which took place on the 2nd December 1805 between the armies of Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire Empire and Tsar Alexander I of Russia against their invading enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte.

In Uhlír’s fascinating account of one of the most famous battles of the Napoleonic campaign, excepting Waterloo of course, he points out that the battle took place on a different day for each of the three armies.

For Francis II, the date was 2nd December 1805, for Alexander and the Russian army the date was 20th November and for Napoleon, Bonaparte it was 11th Frimaire year XIV.

Francis and his army were using the Gregorian calendar introduced in 1582, although it was not universally adopted throughout Europe – indeed, England didn’t change until 1752. Alexander was still using the old Julian calendar – the Russians did not change to the Gregorian calendar until 1918. Napoleon was using the French Revolutionary Calendar, introduced in 1793, but back-dated to September 1792 to mark the beginning of the new republic and each successive year numbered from then on.

It must have caused some confusion for the Austrians and the Russians when agreeing a date to face up to Napoleon and the French would have had to convert the traditional dates into their new scheme.