The AHS Blog

Venner chance comes along, take it

This post was written by James Nye

In November, David Rooney mentioned the Venner time switches in telephone kiosks. This prompted wheels to whir in my brain and I went hunting in my ‘reserve collection’ for something I acquired many years ago, by chance.

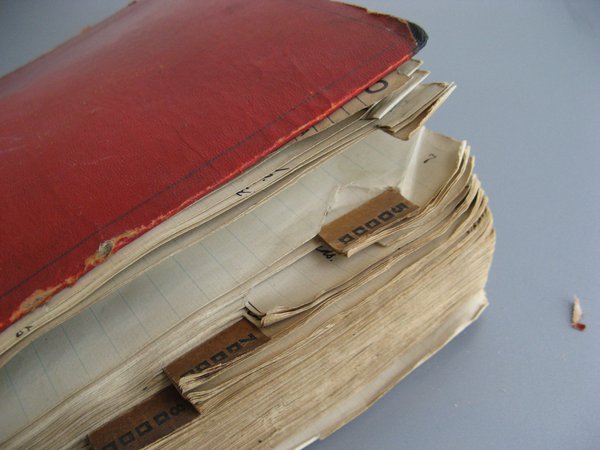

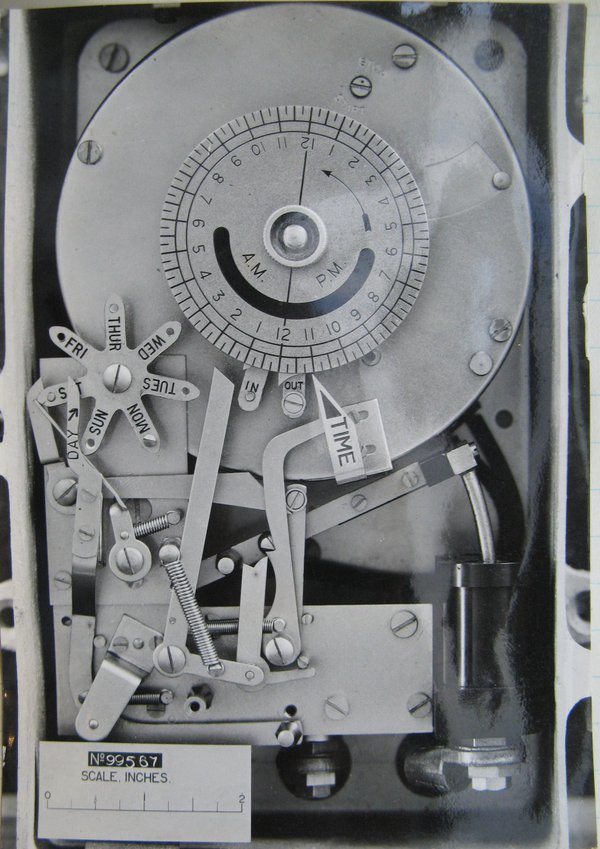

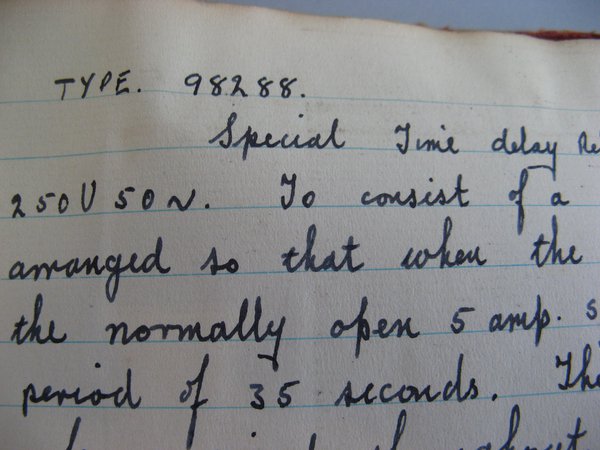

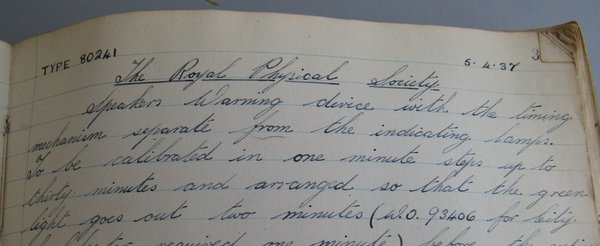

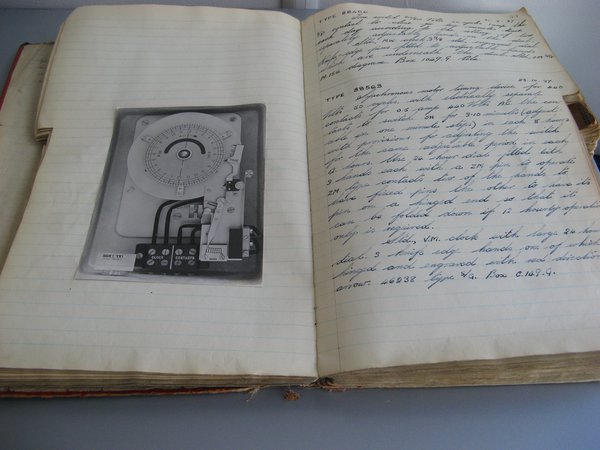

Unfortunately, the history of the firm as presently researched is somewhat sketchy. If anyone is interested in doing so, here is a workshop ledger from Venner, c.1934 onwards. It is a systematically arranged in-house descriptive and photographic catalogue of several hundred ‘specials’, produced from the early 1930s to the late 1940s. Every item had a unique code, all indexed, and most items have a fine quality photograph, with a scale included – these people meant business, and they were perfectionists.

Venner master clocks are finely finished, but this meticulous approach extended to machinery that would probably be invisible throughout its life. As often in the mid-twentieth century, when electro-mechanics were relied on and before integrated circuits, the requirements for accurate timing and switching, perhaps with some programming, necessitated significant mechanical and engineering ingenuity. It is telling that each description starts with ‘special’.

From 1938, we learn that the Royal Physical Society needed a system for lecturers, which would switch a green lamp to amber, one minute before time, and then to red when their allotted slot expired.

In all it is a marvellous piece of ephemera and testament to the very high standards set by manufacturers of mysterious clockwork black boxes which are worthy of closer study.

The sundial column at Seven Dials

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

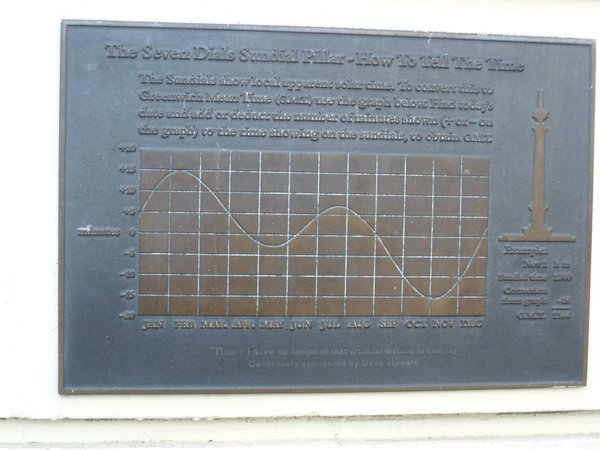

As I live in central London, I often pass through Seven Dials, an area between the districts of Covent Garden and Soho where seven streets meet at a roundabout. In its centre stands a pillar or column with six vertical sundials at its top.

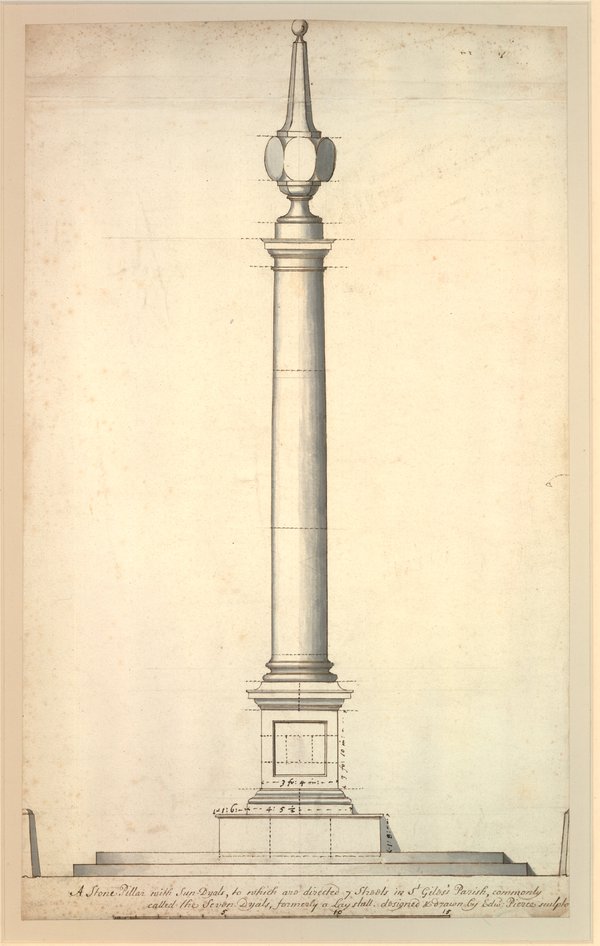

The area resulted from a building scheme of the politician-entrepeneur Thomas Neale MP (1641–1699), whose name lives on in nearby Neal’s Street and Neal’s Yard. He commissioned the architect and stonemason Edward Pierce to design and construct a sundial pillar in 1693-94 as the centrepiece of his development. Pierce’s drawing is in the British Museum and shows six sundial faces.

Why six, not seven? We are told that the column itself was the seventh, so it would act as style or gnomon, casting its shadow on the ground. If so, there must have been a noon mark somewhere. One thing is certain: the column never ‘supported a clock with six dials’, as the London Encyclopaedia tells us.

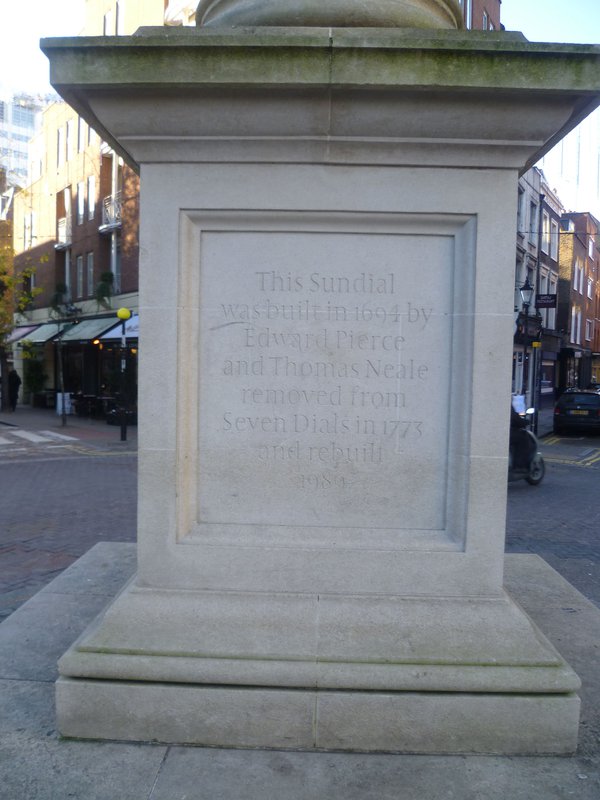

The column that we now see is not Edward Pierce’s original. That was removed in 1773 (in my next blog I will discuss what happened), and for two centuries there was nothing on the roundabout.

In 1984 a charity was set up (the Seven Dials Monument Charity, now Seven Dials Trust), who managed to raise funds to restore what it called 'one of London’s great public ornaments'.

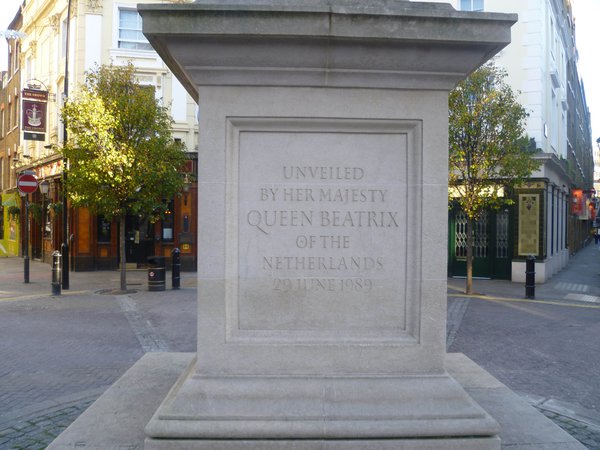

Five years later the new column was unveiled, complete with six new sundial faces in a striking blue colour. There is much explanatory information on and around the pillar. Do have a look when you are next in London’s West End.

All the nation’s oil paintings online

This post was written by David Rooney

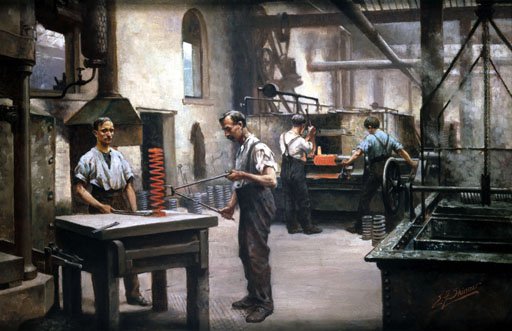

Richard Dunn’s blog post about the Board of Longitude online project reminded me of another exciting digitisation. The ‘Your Paintings' website, run by the BBC in partnership with the Public Catalogue Foundation, aims to show every oil painting held in a UK national collection.

This is a remarkable project. You can see 212,861 paintings online!

I work at the Science Museum, and 297 of our paintings are represented on the site. I picked out three to show you, by Edward Frederick Skinner, depicting file-making and spring-making during the First World War.

OK, they’re not strictly horological, but I think they’re wonderful, and offer a welcome view of women in the engineering workplace too.

This is also an interactive project. You can get involved by tagging the paintings – choosing your own words to describe what can be seen in the images. This will grow to become an important user-generated finding aid.

And so to horology. There are 59 paintings which include the word ‘clock’ in the title. 157 include the word ‘watch’ (though that one’s clearly not such a good search term). ‘Horology’? None, yet, but for ‘antiquarian’ there are three. And there’s one with the word ‘horological’ (the British Horological Institute’s collection is represented).

But that’s titles. Like I said, you can tag paintings yourselves, so if you find a painting which depicts a watch, or a clock, or a fusee-cutting engine or whatever, then tag it – whatever its title – and help others find it in future.

My fellow blog-writers from the British Museum and the National Maritime Museum will doubtless chip in to mention highlights from their own collections. But, really, it’s hard to know where to start! Happy viewing…

Stand up for watches

This post was written by David Thompson

Today we all take the ownership of a plain ordinary watch for granted and such watches are easily purchased at easily affordable prices. The same is true of the cheap and simple clock, be it a wall clock for the kitchen or a carriage clock for the shelf or mantel.

From the latter part of the 17th century until the end of the 19th century it has been possible to purchase a stand which enabled the owner to transform the watch into either a wall clock or a shelf clock simply by placing the watch in a specially made case.

Examples vary in shape and size, but two relatively rare ones are shown here. The first is a splendid tortoise-shell and ebony-veneered stand which can either be wall mounted or table standing. It is designed with an opening front to enable a common pocket watch to be placed inside to perform as a clock. It was made in England in about 1690-1700, and is enhanced by a portrait bust of King William III surmounted by a crown on the front brass decorative panel.

From a similar period is a French example which has a characteristic so-called ‘boulle’ case.

The technique of inlaying brass into tortoise-shell was pioneered in Paris by Charles André Boulle 1642–1732 and in consequence this type of work is named after him, although there were many workshops in Paris using this amazing technique. The material actually used was not tortoise but commonly hawksbill turtle. In some instances the craftsman would make use of the negative and here the pattern on the back is the negative left from producing the brass inlays for the front.

In contrast to these two elaborate and relatively expensive watch stands, lastly is a 19th century stand consisting of a simple folding wooden box which would allow an ordinary watch to be placed on a bedside table for night use.

John Harrison and the Board of Longitude go digital

This post was written by Richard Dunn

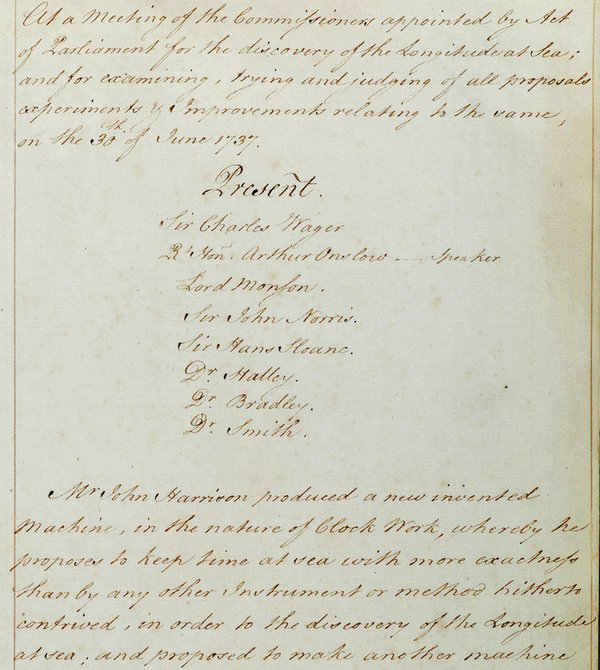

Last week, the Cambridge Digital Library launched some samples of material from the Board of Longitude archive that will interest anyone wanting to know more about John Harrison, the Board of Longitude and the development of timekeeping at sea (among many other things).

Three volumes from the Board’s archive have just been put up: the first volume of confirmed minutes (1737-1779), which includes a full transcription and covers all the meetings involving John Harrison; William Wales’s log from James Cook’s second voyage (1772-75), on which Larcum Kendall’s first marine timekeeper (K1) was tested alongside three by John Arnold; and a group of letters and reports by astronomers and captains from late-18th and early 19th century voyages of discovery.

For all three volumes, there are also links with the collections at Royal Museums Greenwich.

The trial launch is part of a JISC-supported project, ‘Navigating Eighteenth Century Science and Technology: the Board of Longitude’. This is a collaboration between Royal Museums Greenwich and the University of Cambridge that is going to digitise all the surviving archives of the Board of Longitude and related material in Greenwich and Cambridge. The remaining material will go online during the summer of 2013.

The project team would like to get feedback on how the current version works and things they can do to improve it. There should be lots of interesting stuff in the three volumes now online, so please have a look and leave any comments via the feedback function on the Cambridge Digital Library.