The AHS Blog

Falling back

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

It’s that time of year again when our faithful timekeepers quiver, for fear that we will ignore the advice of the clockmaker and attempt to turn the hands backwards, as we return to daily life punctuated by GMT (or UTC if you prefer) on Sunday.

I think it is fair to say that the majority of us are more sympathetic towards the autumnal adjustment, as we can luxuriate in the hour that was ‘banked’ in the spring, so perhaps now is the ideal time to bring this discussion to the AHS blog.

Today, internet searchers will find that the energetic equestrian builder from Petts Wood, William Willett has been eclipsed as the architect of Daylight Saving Time (DST) by George Vernon Hudson, the English born New Zealand entomologist, who first proposed his scheme to the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1895.

In England, thanks to Willett’s monumental efforts, the Daylight Saving Bill was presented before parliament in 1908 and it offered that ‘for a period of 154 days, an increase of sixty minutes more sunshine in the evening of each day’.

The then President of the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill astutely noted in the margins of his copy that this was an ‘optimistic view of our climate!’

Despite Churchill’s support the Bill did not pass and it was eight years before Daylight Saving was introduced as a wartime economy pre-empted by its earlier implementation in Germany.

This Sunday, as you pause the pendulum on your antique clock, will you follow Winston Churchill’s lead and ‘raise a silent toast to William Willett’ and perhaps reflect on the 154 hours of extra ‘sunshine’ that you enjoyed this year?

Conservation and repair of a mystery clock

This post was written by Kenneth Cobb

A disassembled glass and ormolu mystery clock was sent to West Dean College from overseas to be reassembled. A simple enough request, however the 1850’s mechanical mystique of smooth running remained a challenge throughout the three month process.

The clock was made by Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. Born into a family of watchmakers in Blois, France, he was primarily a conjurer and practical joker and this clock is no exception as it is Robert-Houdin’s ‘Fourth Series’ of Mystery Clocks. Onlookers would have wondered at the science of telling the time without the hands being attached to conventional clockwork.

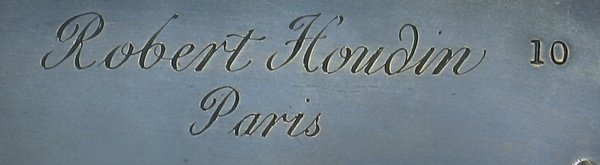

One of West Dean’s key strengths is that conservation departments work together, thus the glass was cleaned by students in the Ceramics Department and advice on cleaning the ormolu was supplied by the Metals Department. Typical of the West Dean conservation approach is Robert Houdin’s signature in copper plate writing on a plate, which was left with the patina as received since it is stable.

The movement itself was a challenge as previous repairs had probably exacerbated its primary weaknesses: the plates are long with a minimum number of pillars to support the tensions of twin sprung barrels thereby making the movement unstable. The lead-off work was hidden within the body of the object. There were so many interconnected links that it was not clear which connection or link was at fault: a question that took weeks to resolve.

Finally, the clock ran reliably and sadly had to be returned as it was a considerable source of interest. As a student, the clock was been a privilege to work on having been a great source of learning and patience, and under the tutorship of Matthew Read and Malcolm Archer I have gained a lot more understanding and confidence in this field.

Can we sex-up the time-recorder?

This post was written by James Nye

We’re used to seeing Hollywood actresses, the latest haute horlogerie on their wrists, gazing at us in dreamy soft focus. But what about the advertisers looking to push horlogerie industrielle?

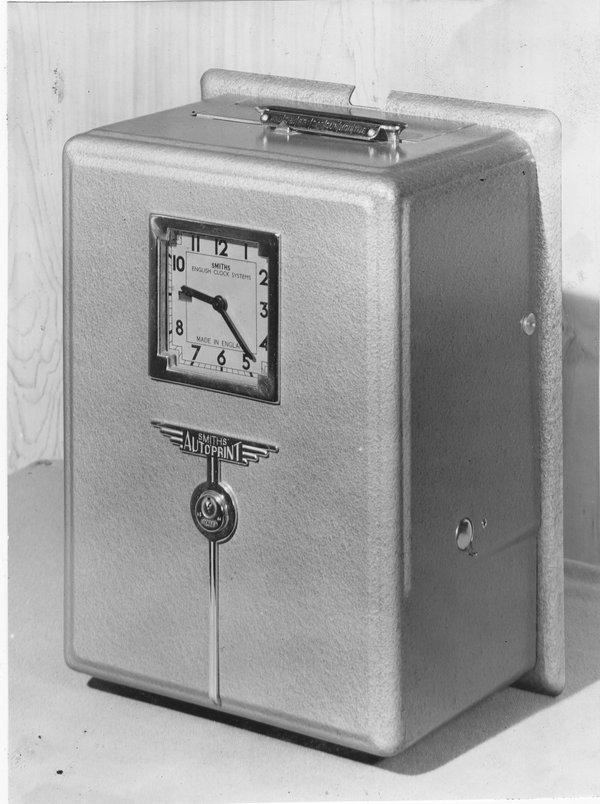

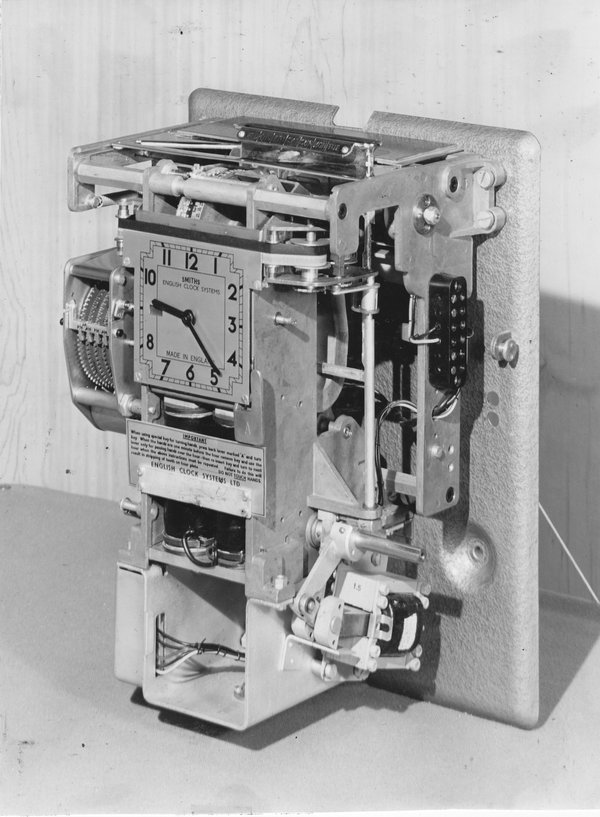

In an earlier blog I presented some pictures from inside the English Clock Systems (ECS) works at King’s Cross from the early 1950s. One of the shots showed the production line for the time recorders. The final product – the Autoprint – was a superb machine, and here are a couple of shots, showing both the mechanism and the outer casing.

The problem facing the ECS publicity unit was how to make the machine a bit more interesting in a catalogue or journal report. Watches and exotic locations were one thing, but the time recorder presented a bit of a challenge on the face of it. In this blog I speculate on the thought process of the lads as they set to their task.

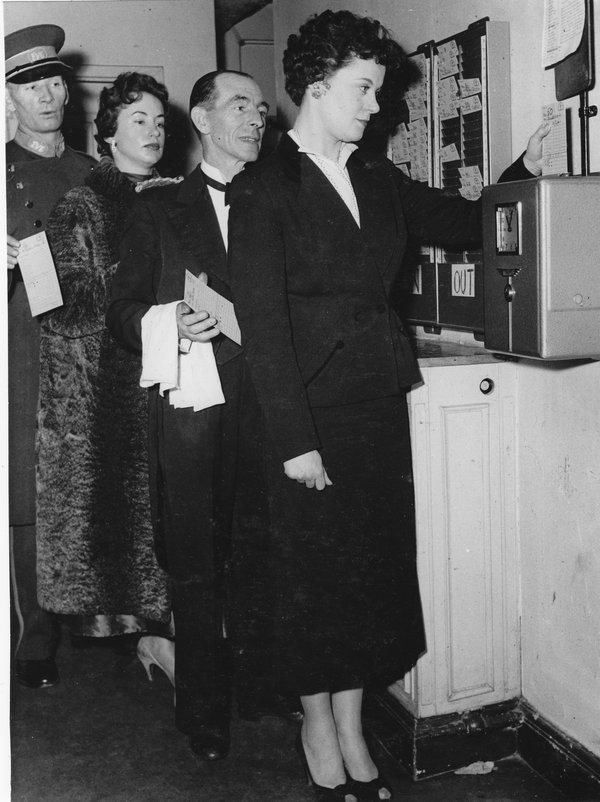

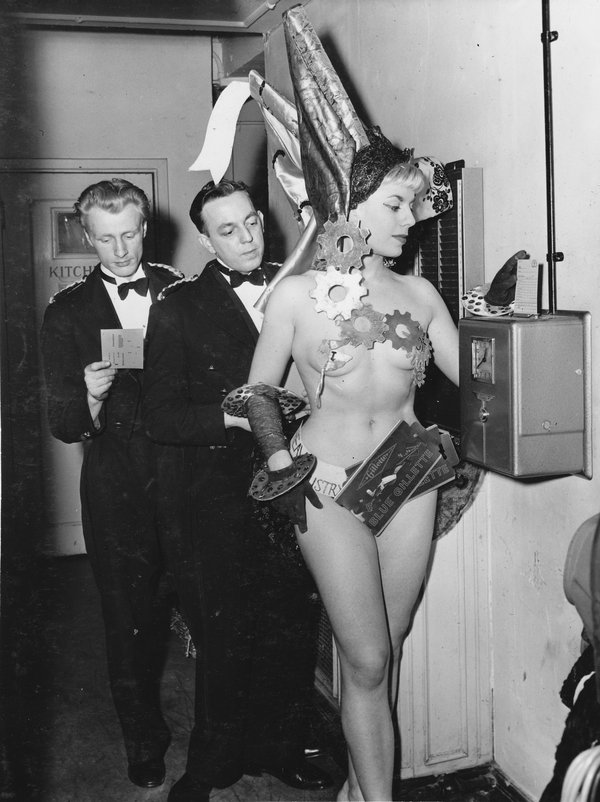

The Autoprint was proudly on show at the 1956 British Industries Fair. The display stand was duly photographed, but an attraction for businessmen that year was a trip to the Eve nightclub on Regent Street. Our intrepid team tagged along, and lo and behold, the nightclub staff used an Autoprint!

A first shot caught the commissionaire and other colleagues stamping their cards, but patience was rewarded with the arrival of a hostess, happy to pose.

Finally, of course, the show-girls themselves arrived – all adorned with representations of items manufactured in Britain. The third image shows Gillette-girl!

Picture Post (7 January 1956) carried a double-page spread on the cabaret, illustrating different industries from the BIF, but the historic industrial horological shot shown here remained hidden in an archive until I stumbled across it recently. In the interests of scholarship I felt it should be published.

A silent turret clock at the V&A

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum who notice the turret clock high up in the entrance hall find no explanatory label. Fortunately there is detailed information on the V&A website.

The 8-day turret clock with hour striking was ordered in 1857 for the newly created South Kensington Museum, as it was then named. It was made by J. Smith and Sons of Clerkenwell and cost £150: £110 for the clock and £40 for the bell and fittings.

A duplicate of the clock was later made by the same firm and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1862 (held on the site of the present Natural History Museum), where it gained a prize medal.

The two dials were designed by the artist Francis Wollaston Moody, who decorated much of the museum, and show allegorical figures.

Day, in a chariot, is followed by a cloaked female figure representing Night; below it is the figure of Time with his symbols: hourglass and scythe. The irrevocability of time is represented by the letters of the word IRREVOCABLE spaced out between the Roman numerals.

To see it properly you need binoculars, but the photos reproduced here – as good as I could manage with a simple camera and amateur skills – give an idea of what the clock looks like.

In 1951 the clock was stopped and silenced, as it was cumbersome for a clock-winder to climb up a ladder, and the booming bell was thought a nuisance for the visitors. Later it was taken down and stored away.

But in the early 1980s it was put back in place, as it was considered an interesting object in its own right, and because of its association with the early history of the museum. It has been converted to electricity, so it shows the correct time even though the pendulum with its heavy spherical bob hangs motionless. But the bell remains silent.