The AHS Blog

'About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks' by David Rooney

This post was written by Chris Andrews

The sentence 'David Rooney has written another book' is one that should make ears prick up.

Rooney, longstanding member of this society and previously of the Science Museum and Royal Museums Greenwich, has already written one short but enjoyable and informative book about Ruth Belville, a history of mathematics to tie in with the Zaha Hadid-designed gallery in the Science Museum, and a monograph about the political history of urban traffic congestion.

His latest book may prove to be the most influential so far, and on the 16th of July over two hundred people gathered virtually on Zoom to hear David give an AHS London Lecture to tie in with its publication (AHS members can watch it here). There are innumerable books presenting the history of timekeeping and even more presenting history in general, but About Time is a rarity for considering how – in the author’s words – 'the story of time is the story of us'.

As someone who is not nearly as skilled in practical horology as some members of the society, I have gravitated towards the historical aspects of the subject. (Of course I do still, in the words of one of our founding members, 'love to watch the wheels go round'.) Those innumerable books about the history of timekeeping have given valuable insights into the innovation and development that has given us the masterpieces that tick in our hallways or on our wrists, but the subject of what those timekeepers mean to us and our lives has so often remained un-tackled.

Not so here, Rooney dives head-first into stories of how clocks have been used to enforce order, fight wars, shame the idle, make money and dream of peace.

I spent a while thinking about how best to describe the field About Time sits in – it is not strictly a history book, nor a technical work about clockmaking – and in the end, it seems like it deserves a new word. My suggestion would be that it is sociohorology, and long may this line of enquiry continue.

Looking inside a Renaissance table clock

This post was written by Víctor Pérez Álvarez

One of the oldest horological artefacts kept at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich is an astronomical table clock made in Augsburg around 1586.

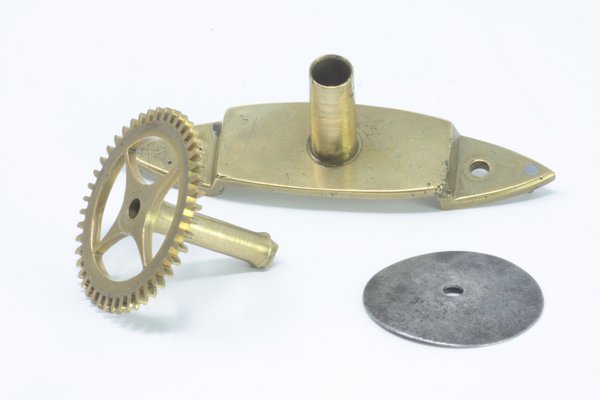

The clock is known to historians of horology, but some interesting findings came to light when it was dismantled in 2017 for a research project funded by a Caird Fellowship granted to me. The clock was partially examined and cleaned at the British Museum in 1967. Then some pieces were dismantled and kept in a separated box, including the count wheel, two chains and three paper washers. There is nothing unusual with these parts, except that the washers have been cut from a scraped drawing, which sparked our curiosity.

The then curator Rory McEvoy began to take apart the clock and another similar paper washer was uncovered under one of the dials. It didn’t help us to identify the drawing, but the mystery was about to be solved. When taking apart the movement, Rory unscrewed a brass bridge and two bigger fragments came to light, this time with a recognizable head: it was a playing card! A clockmaker folded a jack of diamonds and cut it out to the shape of the bridge to fit it in place.

Lots of questions come to our minds immediately: Who put these fragments in the clock and when? Why playing cards? How old were they?

We contacted Paul Bostock, member of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards and playing cards collector. Mr Bostock kindly visited Greenwich to see the fragments and he established that were Parisian playing cards from the 17th century!

What is the strangest thing you found inside of a clock?

Stinky horology

This post was written by Tabea Rude

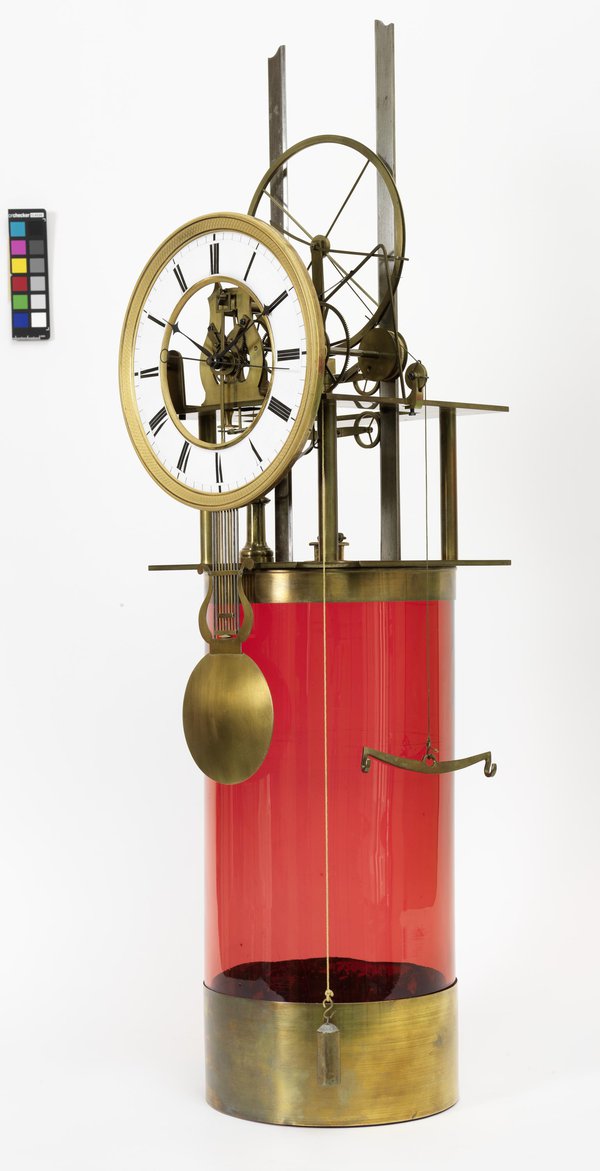

Not many clocks can claim a major olfactory experience by nature of their operation, but this one must have done: the hydrogen clock by Pasquale Anderwalt (1806-1881).

It is mentioned from the early 1840s onwards in several German publications. Anderwalt was a mechanical engineer and worked in Trieste. He developed machines for agricultural use and received a privilege for improvements on windmills. In the 1850s, he was involved in finding and proposing solutions for the frequent shortages of drinking water in Trieste.

For that reason, he was sent to the 1851 World Exhibition in London, to find out what the department of hydraulics and the gathered experts from all over the world had to offer. He also brought his hydrogen clock for presentation. Quite a number of these curious hydrogen clocks survived. Some readers may have seen one of these on display in the Clockmakers Company Collection at theScience Museum. Another is found in the Vienna Clock Museum, with three further examples in museum storage in Vienna and Trieste.

All of them have this rough idea in common: The glass cylinder is filled with sulphuric acid, the owner adds zinc and closes the lid. The zinc then reacts with the sulphuric acid to hydrogen, pushing a piston upwards, which in turn rewinds the weight.

Anderwalt himself claims that 'one ounce of zinc will last the clock machine at least for a human life span'. Probably a very trendy machine in its time, it could definitely compete with other alternative power ideas and not-so-perpetual-motion-clocks. Articles about these have been published in a number of Austrian, Moravian, Italian as well as Bavarian newspapers and scientific reviews. It is not known how many of these objects exploded during use or how smelly they really were.

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

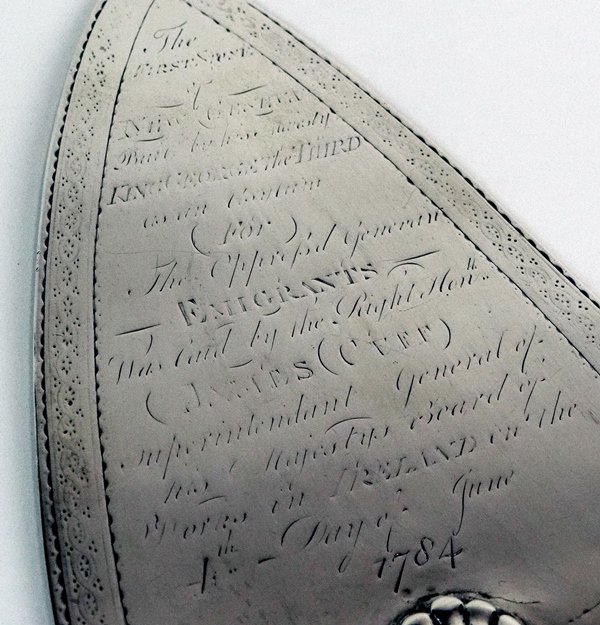

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

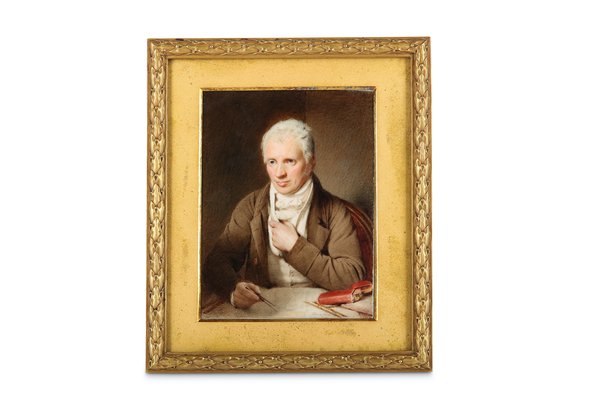

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

The No.4

This post was written by Jonny Flower

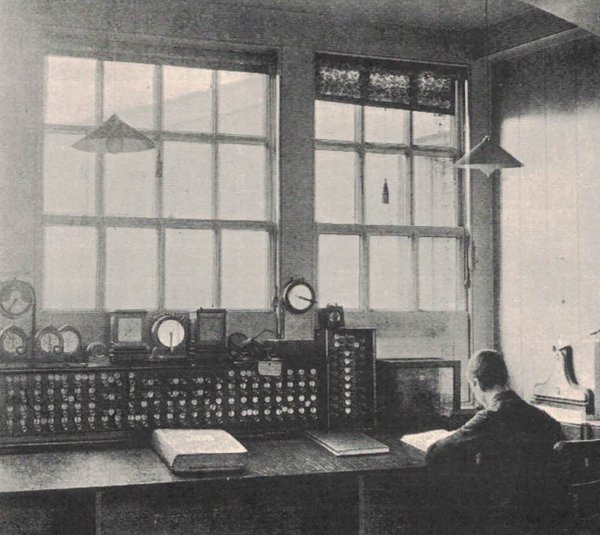

It’s really not every day that a dealer in horological objects gets to make a once-in-a-lifetime report. But, to the door of number 4 Lovat Lane, London, residence of the AHS, to convey news of a handsome discovery! Buried under decades of dust in a darkened room it has been found! Behold…the Synchronome No. 4, which came to me as part of the estate of an electrical engineer.

In photos it looked like it might be a self constructed version, especially with the blue Hammerite paint on the frame. Upon seeing it however, it was obvious that it was factory built.

It was smaller and more delicate than usual Synchronomes and the carvings in the upper door frame were sunrise style, not floral. A very early Hit and Miss synchroniser shows that at some stage it was connected to another Master clock, possibly a Shortt tank.

Once the synchroniser had been removed the bronzed NRA plate engraved with the magical No.4 appeared, one of the very first production Synchronome one-second master clocks.

No pilot dial was evident. The movement had separate footed cocks for the count wheel, latch and the gravity arm. The coils were attached to an L-shaped projection from the main frame casting. The pendulum has a typical steel trunion with adjustable brass sleeve, delicate brass weight tray and a nicely made lead filled bob with small brass shaped rating nut. The impulse pallet was of a shape I had not seen before with stepped sleeve, lipped tip and a separate screwed on support plate for the gathering wire and jewel.

The mahogany case was a design that was used for the early prototype clocks with brass frames and used before the adoption and incorporation of pilot dials.

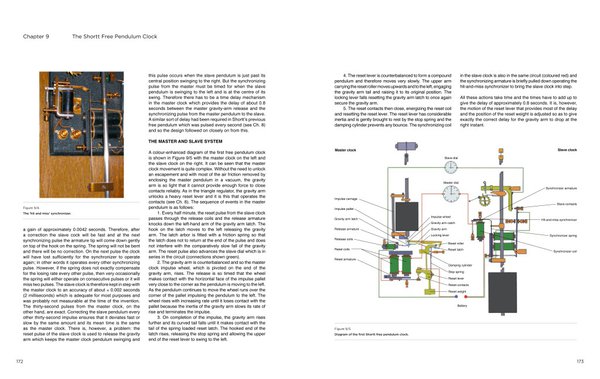

After all these discoveries I consulted friends and colleagues together with all the books and literature to establish where No.4 sat in the time line of Synchronome production. What came to light was that there was a fundamental change in the construction of the one-second master clocks very early on in their production. In Bob Miles’ excellent book on Synchronome he had noticed this too.

This first series of numbered production models I am going to call the Interim Series. The Interim Series of one-second master clocks can be distinguished as follows:

Frame: We know from physical evidence that from serial number 4 up to and including number 41 the cast iron frame had an L-shaped protrusion to support the coils and armature pivot plate.

Movement: Footed brass cocks are used for the Count wheel and gravity arm. The latch used until 1920 is positioned on an adjustable brass frame that is screwed to the back plate.

The back stop is a jewel with a coiled spring-like counterweight that pivots through a pillar attached to the inside of count wheel cock.

No.4 has a case that was used for the brass movement prototypes with a narrow trunk, pediment top and sunrise carvings in the upper door frame. Uniquely at this point in time it is the only one with a door that has the hinges located on the left hand side. No.41 Has a flat topped case with glazed sides. I believe that this Interim Series was a very small production run of approximately 50 pieces with smaller cases and no pilot dials.

My thanks go to John Fothergill and James Kelly for their help, and of course to the late Bob Miles. I am pleased to report that No. 4 will soon be joining the collection of The Clockworks museum in South London.

A musical romp in an antique clock shop

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

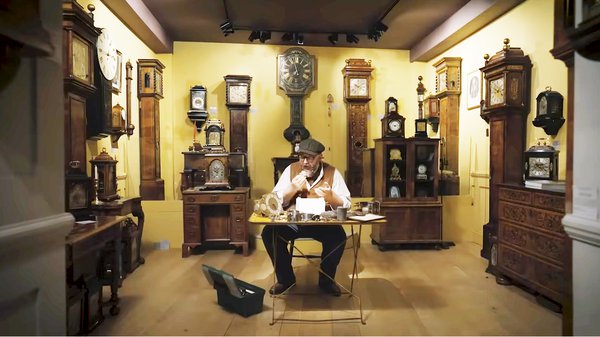

Howard Walwyn deals in fine antique clocks in Kensington Church Street, London. While his shop was closed for normal business due to the Covid crisis, he allowed it to be used for a remarkable musical entertainment: a filming of Maurice Ravel’s comical opera L’Heure Espagnole.

First performed in 1911, the opera is set in a clockmaker's shop in eighteenth-century Toledo. The title can be translated literally as ‘The Spanish Hour’, but the word heure more importantly means ‘time’ – ‘Spanish Time’, with the connotation ‘How They Keep Time in Spain’.

It is the story of a clockmaker and his wife, who hopes to have some private pleasure in the hour her husband is out winding the municipal clocks. However, the presence of a muleteer (here modernized as a UPS courier) who came in to have his watch repaired throws a spanner in the works.

It is a delightful romp – a farce – with two would-be lovers hiding inside the cases of long-case clocks (the pendulums do not appear to have been in the way!) and both ending up being persuaded to buy a clock after the clockmaker has returned.

For more information and a synopsis of the action, see here.

The opera is sung in original French with English subtitles. It is a small affair by opera standards: just 50 minutes long, and only five characters, no choir. It was pre-recorded in the Wigmore Hall in London, and the (excellent) singers acted out their roles in the shop. In this small-budget production the orchestra is replaced by a piano, but that doesn't detract from the pleasure of seeing and hearing it performed with such gusto.

The opera has been staged regularly since 1911, and will undoubtedly have many more performances. But it will never be repeated with such an abundance of authentic ‘props’ as can be seen in this entertaining video recorded in Howard Walwyn’s shop.

Stories of an everyday timepiece

This post was written by Andrew Hyatt

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. One of the things that interest me in horology as a student are the stories that timepieces can tell. Whilst the world changing events of John Harrison’s H1 through to H5 or the exciting life of Larcum Kendall’s K2 do make for fascinating reading, I am talking about the story every timepiece that I hope to end up servicing will tell me.

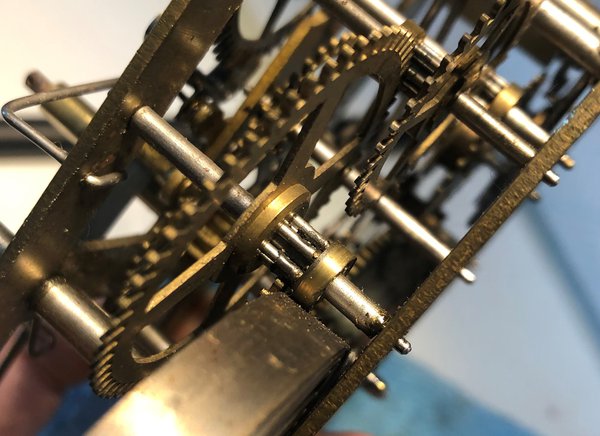

This story is not necessarily the emotional attachment that the owner undoubtedly has to the item. That can be interesting, but in taking apart one of my first clocks I found what I consider to be a much more interesting story.

The clock shown below is a mass produced 2 train clock with a rack striking mechanism. I picked it up because I loved the art-deco style case and the unusually shaped dial.

It is clear that several other people also did as when I took the movement apart my initial observations found a couple of things, the first is that at some point the pendulum suspension spring has been replaced. Both the rod and the back cock have been bent to accommodate a new plastic topped spring shown below.

This made me a little worried about the rest of the mechanism with what appeared to be a quick fix to get the clock running again, but as I continued I found evidence of what may have been a more caring hand. The back cock also shows evidence of the escapement/crutch arbor pivot hole having been re-bushed with the finish almost invisible on the acting face. One of the click springs has also partially sheared, but then its been re-blued.

This tells the story of one or more people that got this clock running again and I am excited to add my name to that list, hopefully in a less noticeable way, as this clock continues its story.

Elizabeth Tower from construction to conservation

This post was written by Jane Desborough

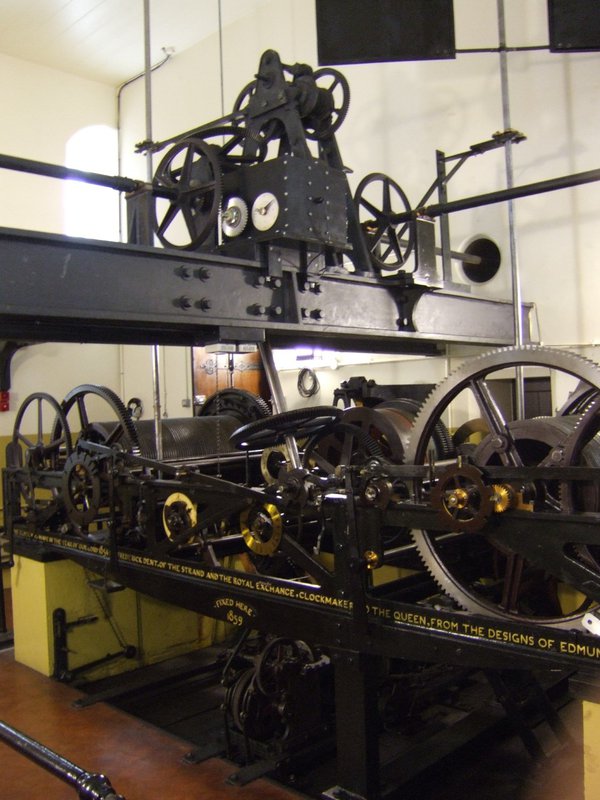

On a cold, dark evening recently my spirits were lifted when I had the pleasure of listening to an online lecture on the conservation work that has been undertaken on the Elizabeth Tower at Westminster.

Presented by tour guide, Catherine, who is clearly very experienced in talking about the Tower, the clock and the bells, it was a really engaging and accessible gallop through the history and overview of the recent conservation works.

For fans of horology, there were no big surprises – most people know the story about the cracked bells and the key players ( Edmund Beckett Denison, Sir George Airy, Edward John Dent and Frederick Dent) involved in the design and making of the clock – but a couple of points stood out for me.

The first was the discovery that when the clock was finished in 1854, it had to wait for the rest of the tower to be complete before it could begin its public service – this was five years later in 1859.

The idea of a paused instrument – one that’s designed to move continuously – made me think that there must have been a lot of work needed to store it safely, maintain it in good condition and to set it going five years after its production. It was interesting to hear that those five years provided some time for experimentation with the escapement.

Another fascinating aspect of the talk was centred on the lamps required to light the dials at night. Recent conservation work has replaced all of the lamps with LEDs.

As a more efficient lamp, the LED will obviously be a good energy-saver. The change makes sense, but I couldn’t help being pleasantly surprised that the same changes being made at a small, household scale are also being made on a larger scale with our public buildings.

For me this talk was great because you can think you know a clock or a building, but there’s always something new to discover!

Opening my first clock

This post was written by Alexandra Verejanu

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. In the context of the lockdown I got pretty behind in my studies as we couldn’t go into the workshop. As I knew it would be helpful to see and touch a mechanism, I decided to buy some cheap old clocks. The clock I have 'played' with brought some interesting questions to my attention.

Firstly, I couldn’t take it out of the case, probably because it didn't seem to have been made to be serviced. I might have stumbled upon one of those old American clocks which were made to look fashionable in the house, but after a few years were discarded as uneconomical to repair. .

I looked closely and it was obvious someone has taken it out of its glued case using some aggressive methods, like bending the bell rod and cutting holes in the case. After two hours of struggling to carefully remove the mechanism from the case, I bent the bell rod and took it out.

Then, I examined the mechanism which was very oily. I knew excessive lubrication can do more harm than good, but I didn’t expect to see damage with the naked eye.

In the future I intend to change the damaged pieces, hopefully with some I will produce in the school workshop.

I decided not to take apart the mechanism just yet, as it was useful as a comparative item to the clocks I was presented with during online courses.

Considering this timepiece is not in its best shape, I might try to do some case work during the summer. I will not be able to fix the cuttings, but I’ll give it a good clean and maybe turn the case into an easy to open one.

This clock was very helpful during lockdown and helped me understand the mechanics of a clock. It truly helped me connect and mesh information from various sources which I was not able to understand.

Special thanks to my teacher Mathew Porton, for taking his time to answer all my questions and making sure I will be safe when I disassemble the mechanism and work on it.

The universe on our bench

This post was written by Tabea Rude

My colleague Amélie Bezárd and I had the chance to take a very close look at a so-called ‘Chronoglobium’ invented and built by Mathias Zibermayr in the first half of the 19th century in Brno (today’s Czech Republic) and Graz (Austria).

His invention, a terrestrial globe driven by a gear train including small models of the Sun and Moon within a static glass celestial globe, was intended as a teaching device to demonstrate the movements of the heavenly bodies.

Zibermayr built at least 18 of these machines, which enjoyed great popularity not just at the time, but also much later when this particular model entered the Vienna Clock Museum in 1951. Almost immediately, it appeared in the Vienna newspapers and on the museum catalogue cover page.

The machine can either be operated using a hand crank to show the movements as a time-lapse, or by a spring-driven clock movement, which also shows the time of day and day of the week.

Within the glass sphere, the shadow-hoop with ecliptic stands vertically, screwed into the back of the supporting Atlas figure. The outer hoop is fixed and shows the day of the month indication. The inner ecliptic is a gear wheel that is firmly attached to the models of Sun and Moon.

These models are attached on long arms on the rear side of the Chronoglobium. The model Sun is firmly attached on the ecliptic with a fan-like grid indicating the direction of Sun rays onto Earth.

The model Moon is moved by way of a mechanism including two wheels and two lever arms up and down to demonstrate the elliptical movement of the Moon in relation to the Earth. The models of Moon and Sun perform a whole rotation around the terrestrial globe once a ‘year’, indicated by the moving ecliptic.

A few examples of contemporary typography in watchmaking

This post was written by Lee Yuen-Rapati

The evolution of typography in horology has come a long way from the dominance of Roman numerals and the round hand script. While the mid-twentieth century remains a potent library of inspiration for today’s watch brands, other watchmakers look forward in creating their timepieces.

These contemporary watches can appear non-traditional or even avant garde, with typography to match. However a closer look reveals that even the newest typography on watches still has connections to the past.

The use of bold and blocky sans-serif numerals is a common trend in many contemporary watches that try to eschew a sense of antiquity, at least on the surface. A prime example is the collection from Urwerk who have consistently used a bold and angular style of numerals since their inception in the late 1990s. The ultra high-end pieces from Greubel Forsey also feature rather rectangular numerals which both match the aesthetics of their main collection, but provide an interesting juxtaposition in their Hand Made 1 as well as the Naissance d’une Montre (1) watch, both of which highlight more traditional watchmaking techniques.

The use of bold and blocky numerals is more of an evolution for a company like Rolex who have adopted them across their recent collection, notably on the Explorer and GMT-Master II models. While none of the examples above are likely to be mistaken for antique pieces, similar rectangular or blocky numerals were popular in the art deco era and into the mid-twentieth century. Even if the watch is new, the link to the past is sometimes quite prominently promoted as with the unabashedly contemporary (and divisive) Code 11.59 collection which features numerals adapted from a 1940s Audemars Piguet minute repeater.

Some contemporary watches pull from outside the horological world to define themselves. Hermès as well as the young company anOrdain each sought out type designers to create new and identifiable typography. Hermès got its modernist numerals from the studio of Philippe Apeloig for its Slim d’Hermès line while anOrdain’s typographer Imogen Ayres created numerals inspired by survey maps. Neither brands’ numerals are completely new, but their lack of typographic precedence in the watch world make them both stand out.

Other brands use more traditional numerals but change the material in order to place their watches firmly in the twenty-first century. H. Moser & Cie’s Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue uses applique numerals that are inspired by 1920s pilot’s watches. The appliques are made from the luminous material Globolight rather than metal. In a similar fashion, the refounded British brand Vertex uses moulded Super-LumiNova numerals in lieu of traditionally painted or printed numerals on their military-inspired watches. Kari Voutilainen offers the option for brightly coloured arabic appliques on his watches which bring a youthful presence to his more classically designed dials. Dimensionality has long been a useful styling tool for watchmakers, and the inclusion of new materials has produced some very refreshing results.

The examples above represent a few different typographic paths for the contemporary watchmaker to follow. While these watches and their typography may appear to share very little with antiquity, there are always links to trace back, they are simply being shown from a new angle.

Photo credits:

- Baruch Coutts @budgecoutts (Urwerk, UR-UR111C)

- Greubel Forsey (Hand Made 1)

- Atom Moore @atommoore (Rolex, GMT Master II)

- Audemars Piguet (Code 11.59 Selfwinding White)

- Baruch Coutts (Hermès, Slim D’Hermès Titane)

- AnOrdain (Model 2 Blue Fumé)

- H Moser & Cie (Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue)

- Vertex (M100)

- Atom Moore (Voutilainen, TP1 OW2019)

A bad time in Znojmo

This post was written by James Nye

In my January 2021 London Lecture on Johann Antel (1866–1930), the Czech/German clockmaker (available to AHS members here), I condensed much, and stories were omitted, like this one–a disastrous episode.

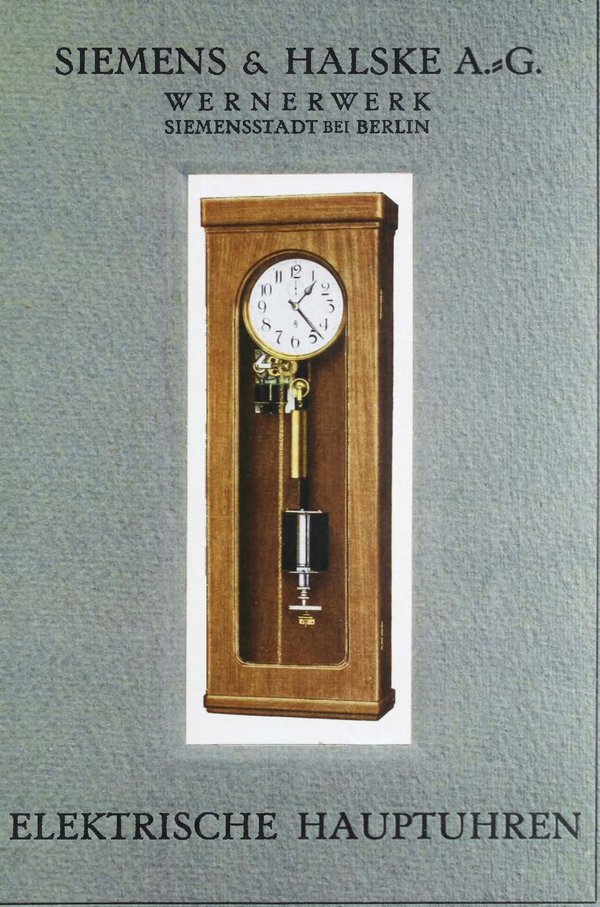

In 1930, the Znojmo authorities sought quotations for a clock for the bus-stop in Divišovo Square. Antel himself died that July, but his firm won the tender, offering a four-sided rooftop subsidiary clock, driven by a minute-impulse transmitter clock. Antel would source it from Siemens and Halske of Berlin, or its Prague subsidiary Elektrotechna.

Installation started in February 1931. In lifting the clock housing onto the bus-stop roof, the ladder slipped and both technician and clock fell to the pavement. Six weeks were lost in repairs. It was finally installed 24 March 1931. But regular attendance by the technicians over the next month suggests all was not right from the beginning.

Antel’s widow Ludmilla issued proceedings to secure payment, but matters dragged into 1932. The legal papers are actually a wonderful source of information on this catastrophic installation. The original drawings showed dials with numerals, but Antel’s firm delivered a clock with four plain dials, claiming they looked more ‘modern’.

No! said the town, we want numbers!

They also wanted a thicker gauge of glass, as the night-time illumination revealed too much of the motion-works, and the lamps were so bright the hands were invisible. A hand went missing, perhaps the fault of the technician who upgraded the glass.

In July 1933, the local paper Nas Týden reported all four dials showed a different time. A satirical piece followed in Ochrana in October, urging civic pride in a clock that showed different times on different dials, like the astronomical clock at Olomouc.

The gods never favoured the clock, and it was probably replaced in around 1938. As with an ill-fated earlier installation at the law-courts, Antel never had much luck in Znojmo.

The engineer’s chronometer: William Wilson and the Adler

This post was written by Allan C. Purcell

Last Summer I bought on eBay this fusee chain driven watch with detent escapement, dia 50mm, hallmarked Chester 1858, signed on the movement ‘William Benton of Liverpool, No. 5115’, and on the dial ‘Chronometer watch by William Benton 148 Park Road Liverpool’.

In the description of the watch, the seller had written ‘Opening below to reveal a highly decorated dust cover “Stephenson’s Rocket, Steam Train”, and clean fully working highly decorated “Steam Paddle Ship”.’

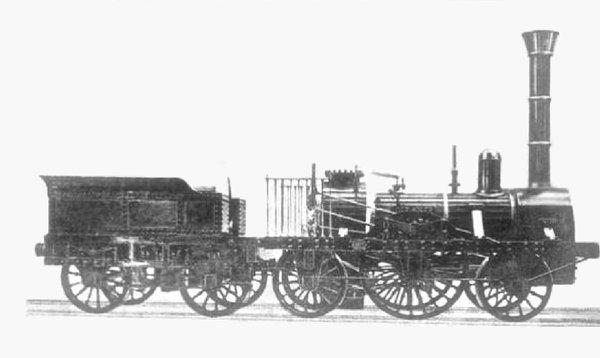

What the seller failed to point out is that the watch is inscribed on the dustcap ‘WILLM WILSON / LIVERPOOL / AD 1859’. It is my belief that this was the English engineer William Wilson (1809-1862), and that the locomotive illustrated on the watch is not the Rocket but the Adler (German for: Eagle), the first locomotive successfully used commercially for the rail transport of passengers and goods in Germany.

In 1835, George & Robert Stephenson in Newcastle were contracted by the Bavarian Ludwig railway company to build an engine for their first railway to run from Nuremberg to Furth. They sent the new locomotive packed in boxes, and their engineer William Wilson was contracted to rebuild it there. The train was a huge success and Wilson stayed with the Ludwig railway company for another twenty-five years, driving the train in all weathers. In 1859, William was covered in glory by the German railway company. In 1862 he died and was buried in Nuremberg, where his descendants are still living.

While Stephenson’s Rocket has only four wheels, the Adler had six wheels (wheel arrangement 2-2-2 in Whyte notation or 1A1 in UIC classification). The engraving on the watch shows a locomotive with six wheels. The image of the ship engraved on the watch may refer to the steamboat Hercules which in September 1835 had been used to transport the boxes containing the locomotive from Rotterdam on the Rhine to Cologne.

When in September last year I went to Nuremberg for the Ward Francillon Time Symposium, I arranged an appointment with Stefan Ebenfeld, the director of artefacts and library at the Museum of the German Railway (Deutsche Bahn Museum) in Nuremberg. It turned out that the museum had no personal artefacts of Wilson’s, and we agreed that the museum would buy the watch from me for the price I paid for it.

For anyone interested in more details, there are entries on William Wilson and the Adler on Wikipedia.

Put down your pens: the Oxford Examinations School clocks

This post was written by Johan ten Hoeve

Located on the High Street, in the heart of Oxford, the Oxford Examinations School was built between 1876 and 1882 and made the reputation of its architect, Thomas Jackson, who incorporated materials from old buildings to construct the school. Among them, Christopher Wren’s pulpit from the Divinity School forms the Examiners throne in the North School, and many now regard the building to be Jackson’s masterpiece.

In 1883 Charles Shepherd (Jr) installed a master clock and slave system with 19 slaves. This was replaced with an expanded Gents master system, with 28 slave dials, in 1959. The current dials, which are some 30 inches across, are replacement dials, having possibly been installed along with the Gents system.

Most of the original wooden housings of the slave clocks are still fitted with the old Shepherd terminals which connected the slave clock to the system. This is the only remaining evidence that there was once was a Shepherd clock system. However, the original Shepherd master and a slave clock are still around, and can now be found in the reserve collection of the History of Science Museum, Oxford.

The slave unit is described thus: “Slave unit to the Shepherd electric master clock (78037), the mechanism closely resembling that of the master. The slave unit receives the impulse every two seconds and moves the hands of the dial. The unit has two hands but no dial. Mounted on wooden board, with unfitted Perspex cover”.

The Gents slave system still operates in the Examinations School even though Gents ceased the clock side of their business in 1999 and terminated the contract. The 28 slave dials are divided up into three sub circuits; one C73 and two C74 relay units, with a power supply, trickle charger and battery back-up.

At present, the whole system, (master and all slave clocks) is undergoing a major overhaul and service.

Was there high-quality, wholesale, clock movement manufacture in seventeenth-century London?

This post was written by James Nye

There is a fascinating article in the latest edition of Antiquarian Horology, just starting to arrive through people’s letterboxes, setting out a remarkable research question which cries out for some crowdsourcing of data—hence this blog post. For those who don’t receive a physical journal, the editor has conveniently made it the sample article for this quarter. You can download it here.

Put simply, it is suggested a range of prominent makers (or perhaps retailers) bought in largely finished movements from a single source, and arranged for their casing/signature/final finishing.

This is clearly a very well-understood practice in the watch world from a relatively early date, and was certainly common practice in the clock world later on. For example, Thwaites produced movements for a wide range of other clockmakers and clockmaking firms, and on a large scale.

The question remains, how early did this standard practice emerge, and is there sufficient physical evidence to allow us to draw firm conclusions?

The key element is that Jon’s piece is a call to arms! More data is needed. And it is not difficult to look for it. This is a massively worthwhile project to support, and whatever the outcome, if you can supply data you can play a part in improving our understanding of clockmaking practice in London in the period 1660–1720. Please do get involved!

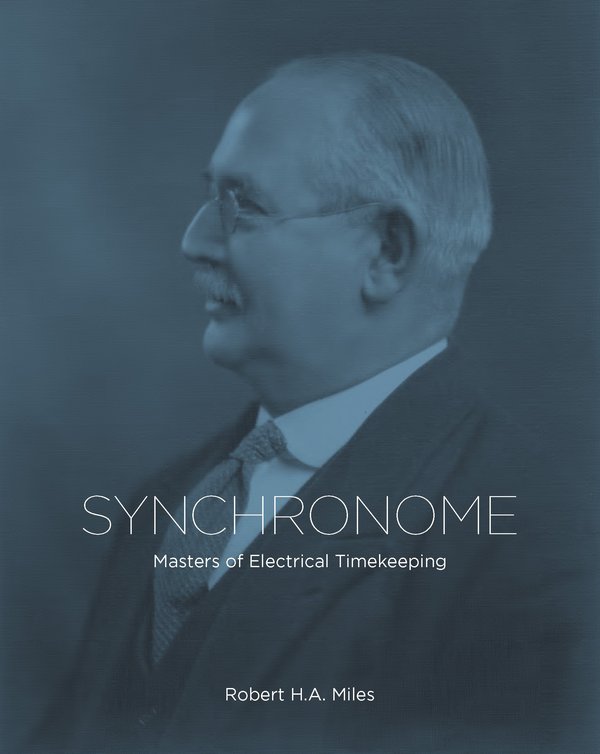

The second edition of 'Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping'

This post was written by Charles Ormrod

Robert Miles’s landmark work, Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping , sold out a few years after its original publication in 2011. Since then, copies of this highly sought-after book have been selling for several times the original cover price of £50.

The AHS is therefore delighted to announce that a long-awaited second edition is now available, made to the same standards as the first, hard-backed and thread-bound, at a new low price of just £25 plus postage.

As a humble labourer in the vineyard of the second edition, assisting James Nye with administrative work but certainly not with Synchronome expertise, I’ve had a first-class opportunity to learn about the pitfalls of editing, proof-reading, and the finer points of book production.

The possibility of a second edition was mooted some years ago, and revisions to the first edition had been contributed by Bob Miles himself, Derek Bird, Norman Heckenberg, Arthur Mitchell and others.

One of my first jobs was to combine these various sets of revisions into one document, eventually about eight A4 pages long, for presentation to the designer of the first edition, Phil Carr. Phil very generously made no charge for all the work of entering revisions into a new version of the original book’s electronic file.

Double-checking the changes and exploring disagreements between contributors led to many absorbing hours searching for clarification. I now know far more than I did about the history of sonar and the extent to which Second-World-War sonar sound-pulses fell within an audible range (which depended on whether the listener was a fit young sailor or an old sea dog).

I also learned about the Doppler effect on the sound of swinging tower-clock bells, the problems of reproducing the appearance of pre-war electrical flex, alternative cabinet-making methods applied to Synchronome cases, and the best method of setting up the suspension of a Synchronome pendulum.

I must admit I hadn’t quite realised that high-quality hard-backed books, such as the first and second editions of Synchronome, really are still made by sewing groups of double pages together with thread. A machine does the sewing of course, but the principle is broadly the same as with the earliest surviving bound books of the eighth century.

A thread-bound book is much easier to use than a glued paperback because the pages naturally fall flat when the book is opened, and thread-binding lasts far longer.

This second edition of Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping is dedicated to the memory of its author, who died earlier this year in the knowledge that work on a new edition was under way. The book is available to order on the AHS website via this link.

The unexpected visitor

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Almost exactly ten years ago I had John Harrison’s magnificent first marine timekeeper H1 in my workshop at the Royal Observatory. It was being dismantled for study, cataloguing and conservation for the new chronometer catalogue.

I had a film crew with me making a documentary, and they were becoming exasperated at constant interruptions to the filming. Finally another telephone call – a man was outside, asking if he could see me. Embarrassed, I assured the film team I would politely ask him to come back another time, but explained they had to come with me as I couldn’t leave them alone with H1.

Outside, the man apologised for arriving without warning and that he could come back if necessary. He introduced himself, offering his hand and just saying softly “Neil Armstrong”.

One of the film crew laughed and remarked 'Ha! I bet with a name like that you get lots of requests for autographs!' to which the unassuming gent simply replied: 'I’m afraid I don’t do autographs'.

It was at that point that we collectively realised that we were indeed in the presence of history. Suffice to say, all anxieties about filming schedules melted away and we all returned to the workshop (but with film cameras firmly switched off!)

Armstrong had long been a Harrison fan and he and his golfing friend Jim, hearing on the grapevine about the H1 research, had taken a detour from a sporting trip to Scotland, to make a pilgrimage to Greenwich.

For a wonderful hour or so we discussed Harrison and his first pioneering longitude timekeeper and it was clear Armstrong’s reputation was correct – reserved, yet of great intelligence and hugely well-informed; in short, a thoroughly nice man and not at all the showman one imagines when thinking of lunar astronauts.

I always asked visitors to sign my Visitors Book, but understood when Armstrong explained 'if you don’t mind, I’ll do it in capitals'.

Hearing that Harrison’s second prototype timekeeper, H2, would be next for research in the coming year, Armstrong returned and I spent a little more time with him, getting to know him a little better and was privileged to learn more of the Apollo 11 mission, from the horse’s mouth, as it were.

As he and Jim left on that occasion I asked Jim to sign my book again, and as they got back into their car, Jim whispered to me 'I think you’ll find Neil signed properly this time too'.

And indeed he had, something I shall always treasure.

Star of the show

This post was written by James Nye

At the Mannheim electric clock fair, now in its twentieth year, one unusual item usually attracts a lot attention.

This year (2019) was no exception. The images show an early form of German ‘treppenhausautomat’, loosely a ‘staircase lighting timer’. Lighting, and therefore electricity consumption, has always been expensive.

An intriguing question, worthy of some serious research, is the economic justification for the complicated (and also expensive) electro-mechanical devices used (late 19th/early20th C) to reduce consumption.

In large houses, or multiple-occupancy blocks, it’s always made sense to add press-button switches to control stairwell lighting—the lamps remaining lit for a set period before being switched off.

Modern switches incorporate integrated circuits, but for a long-time such devices used a pendulum clock as the timebase.

The object here dates to c.1905, and was sold by Paul Firchow Nachfolger, from 3 Belle-Alliance-Strasse in Berlin. The clock mechanism is a standard volume production element, unsigned, and perhaps from Lenzkirch.

The hands are arranged to carry an adjustable set of contacts which will make a circuit, naturally for night hours, but with the capacity to set the operating hours (accommodating seasonal variations).

Assuming it is night (dial circuit closed), pressing a push-button in the stairwell will activate the motor below the clock, which in turn will revolve the drum.The drum has brass (conductive) sides, embraced by brass slide contacts.

The drum has a narrowed section, and when this arrives between the (wider) contacts, the circuit is broken.

The cycle lasts around three minutes.

The top panel shows ceramic entry ports for various cables: knöpfe (push-buttons), power, lampen (lamps), and two set of widerstand (resistance). The machine will switch 110V and up to 18 amps, so a significant load is possible.

The clock is a forerunner of more typical, volume-produced ‘black boxes’, but its complex form (and by inference its high cost) is a strong signifier of the importance placed upon saving money and controlling power use.

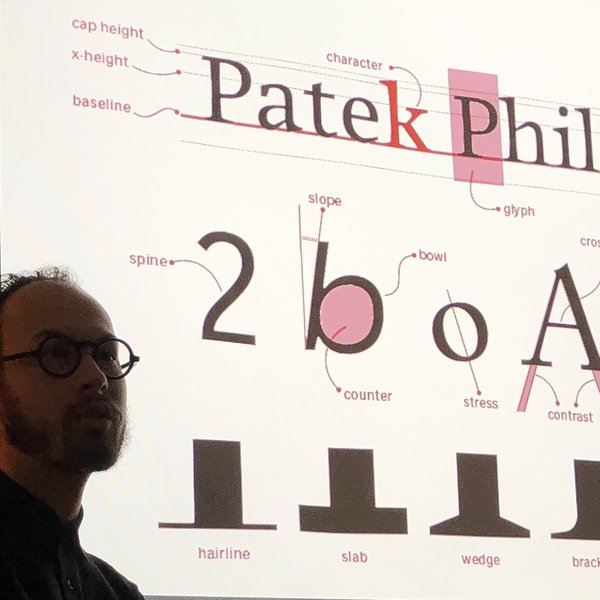

The typography of revival watches

This post was written by Mat Craddock

Until recently, there had been little research carried out on the typography of wristwatch dials. However, over the past decade, the increased interest in collectable vintage wristwatches appears to have sparked the interest of brands and collectors alike.

While wristwatch collectors’ focus has largely been on the variations in logo, layout and content of vintage wristwatch dials, interdisciplinary designer Lee Yuen-Rapati has taken a critical look at the typefaces used, and typographic decisions made, by watchmakers.

His Masters dissertation, titled ‘Motivating Factors In The Trends Of Horological Typography,’ formed the basis of an AHS Wristwatch Group talk at The Clockworks in April.

Lee’s research covered clocks, pocket watches and wristwatches, and looked at type and numerals used on the dials, identifying various themes and typographic pitfalls that appeared to be specific to wristwatches.

His research included interviews with brands and independent watchmakers about their typographical decisions, the typefaces they use and the importance of type design to their brand.

His talk focused on the typography of contemporary wristwatches that had revived distinct vintage or antiquarian styles.

Highlights included the use of system (or default) fonts by high end watch manufacturers, the technical limits of pad printing, the benefits and traps of modern processes involved in dial design (such as the digital workspace) and inconsistent choices made by watch brands when reviving older designs. Examples of recent wristwatches from Longines, Nomos and Stowa were used to illustrate these themes.

As a codicil, Lee discussed recent advances in dial printing, such as the use of physical vapour deposition on the zirconium ceramic dials of the Charles Frodsham Double Impulse Chronometer, suggesting that this technology might be taken up by other watch manufacturers, necessitating an increased focus on typographical principles and design choices.

Follow The AHS on Instagram: @thestoryoftime

Lee Yuen-Rapati: @onehourwatch

Mat Craddock: @the_watchnerd

Dreaming of a clock in the slums of Paris

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every clock that left the workshop or factory on its way to a buyer has, we may assume, been coveted by and, we may hope, given satisfaction to its owner. But most of this goes unrecorded, and where traditional non-fiction sources are silent, we may find some glimpses in fiction.

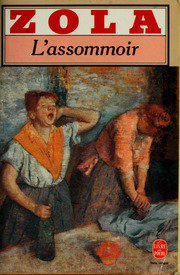

For vivid descriptions of the life of the workers in nineteenth-century France one can do worse than turn to the wonderfully naturalistic novels of Emile Zola (1840-1902).

The book that shot him to fame in 1877 was L’Assommoir; below I quote from the most recent English translation: The Drinking Den , Penguin Classics 2000 rev. 2003, translator Robin Buss.

The novel depicts in graphic style the rise and fall of Gervaise Macquart, who worked as a laundress in Paris during the period 1850 to 1870. There are scenes of abject poverty and alcohol is a key character in the story; but there are also comical scenes and uplifting passages. It is a masterpiece. As one author has put it:

‘L’Assommoir is set in the dirt and filth of working class Paris, where life was hard and lives depressingly short. He researched in great detail the impoverished quarter of which he wrote, so that the work is an ethnographic novel and probably the first of its kind’.

In the poor household of the young Gervaise, a chest of drawers takes pride of place:

‘One of her dreams, which she did not dare mention to anyone, was to have a clock to put on it, right in the middle of the marble top – the effect would be quite splendid. Had it not been for the baby that was on the way, she might have risked buying her clock, but as it was she put if off until later, with a sigh.’ (p. 97).

Three years go by before she is able to act on her desire:

‘She had bought herself a clock; and even then this timepiece, a rosewood clock with twisted columns and a copper gilt pendulum, had to be paid off over a year, at the rate of five francs every Monday. She got cross when Coupeau [her husband] said he would wind it up, because only she was allowed to take off the glass globe and religiously wipe the columns, as though the marble top of her chest of drawers had been transformed into a chapel. Under the glass cover, behind the clock, she hid the savings book. And often, when she was dreaming about her shop, she would sit there, miles away, in front of the dial, staring at the turning hands, for all the world as if she was waiting for some particular, solemn moment before she made up her mind.’ (p. 108).

The ‘dreaming about her shop’ refers to her ambition to make herself independent and set up her own laundry, which indeed she eventually manages to do. Life looks good, she even entertains a large group to a celebratory dinner in the laundry shop.

But it was not to last, and as her life goes in a downward spiral, Gervaise is forced to bring one possession after another to the pawnbroker. She puts a brave face on it:

‘Only one thing broke her heart and that was putting her clock in pawn, to pay a twenty-franc bill when the bailiff came with a summons. Up to then, she had sworn she would starve rather than part with her clock. When Mother Coupeau [her mother in law] took it away in a little hat box, she slumped into a chair, her arms dangling, tears in her eyes, as though her whole fortune had been taken away’. (p. 279).

There is more horology in this novel. She also has a cuckoo clock, which would have been a much less valuable object, but it is never described in detail. Neither is the watch which only once makes an appearance, on the day that she is forced to put it in pawn as well:

‘The little knick-knacks had faded away, starting with the ticker, a twelve-franc watch, and the family photographs.’ (p. 384).

There is also a watchmaker who plays a small role in the story. In the courtyard of the tenement house where she lives are various workshops and shops, including – for a while – her own laundry shop:

‘At the bottom of a hole, no larger than a cupboard, between a scrap-iron merchant and a chip shop, there was a watchmaker, a decent-looking gentleman in a frock-coat, who was continually probing watches with tiny tools, at a bench where delicate things slept under glass covers while, behind him, the pendulums of two or three dozen tiny cuckoo clocks were swinging at once, in the dark squalor of the street, in time to the rhythmical hammering from the farrier’s yard’ (p. 134).

Literary critics may argue that in fiction, clocks and watches are often introduced as symbols, and that therefore novels do not necessarily give a realistic image of the ownership of clocks and watches.

Be that as it may, the story of the struggling laundress Gervaise Macquart, who dreamed of owning an ornamental clock and managed to bring one into her poor home, only to have to part with it again, feels very real indeed.