The AHS Blog

The worst of times

This post was written by James Nye

I have been musing on the destructive power of war in the lives of various clockmakers and their families.

Consider an obscure Brno clockmaker, Johann Antel (1866–1930). Sporting a boater, his two daughters, Anna and Edith, are ranged left and right – circa 1913. The Antels, from Bohemia, had long German ancestry. In the Great War, Johan lacked vital materials for important commissions. When he died in 1930, the local clockmakers, ethnic Czechs and Germans, all stood for a minute’s silence.

The Nazis arrived in 1938 and it was expedient to prove Germanic ancestry. The archives record the remaining family’s declarations. Daughter Anna had been an apprentice in her dad’s clock shop in Brno, so she was now in charge, along with her mother Ludmilla.

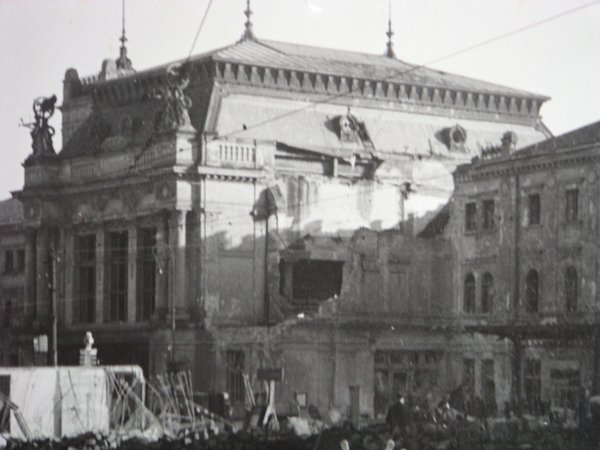

With the arrival of war, nothing was safe – even clock shops were bombed – witness the damage to the Antels’ place.

When war ended, the rules changed. Being Czech was suddenly useful and extraordinarily the archives record sister Edith declaring precisely that, and succeeding because she had sheltered a Jewish engineer, Ing. Michaelstadter, whom she duly married.

She stayed in Brno, dying in 1981, while her ‘German’ sister Anna had to flee to Vienna for the rest of her days, dying in 1984.

We only know about Antel because of a 1944 RAF raid on Brno, which set in train a series of events, leading to the station clock emerging in the 1990s.

But war is not a one-way street. What about the Luftwaffe over London? A 1941 raid caused the dramatic collapse of 19–21 Queen Victoria St, taking Standard Time with it.

In an archive last week, I realised that exactly the same raid flattened Samuel Smith’s old jewellery shop on Newington Causeway.

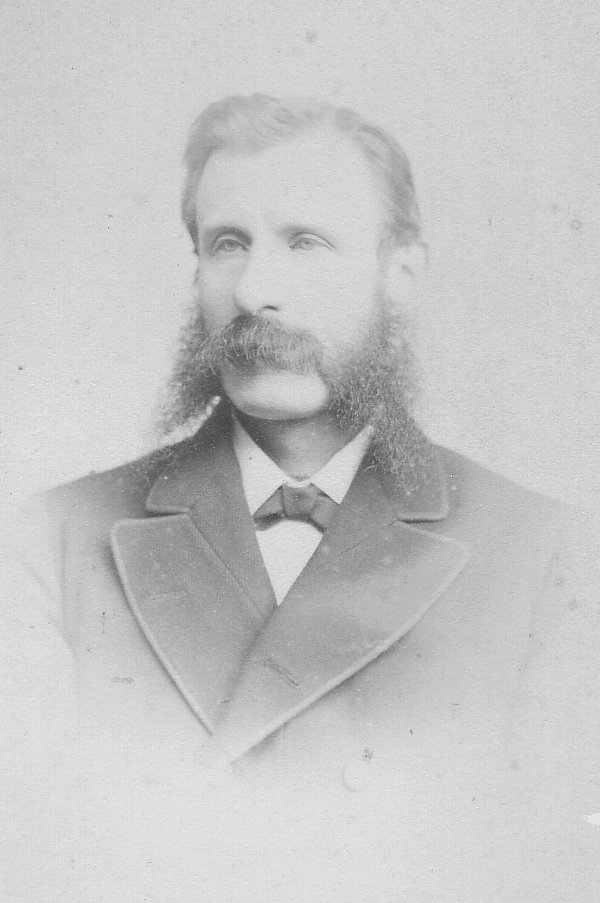

John Hoch (1836–1918) worked there for Samuel Smith in the 1870s. Originally from Rheinland-Pfalz, he lived in London, with magnificent sideburns, for the rest of his life. But he was in the wrong place at the wrong time in 1914 and anti-German feeling made life very hard – some of his children even changed their surnames and emigrated.

Hoch didn’t quite make it to the Armistice, dying in the summer of 1918. But you can call on him in Norwood cemetery.

The Silver Swan fictionalized

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The latest novel by the Australian author Peter Carey, The Chemistry of Tears, was inspired by the Silver Swan of Bowes project.

The Swan is an amazing late 18th-century, life-sized automaton, incorporating three clockwork mechanisms or movements, products of the clockmaking trade. It has been in the Bowes Museum in County Durham, Northeast England, since 1872 where it can be seen in action every afternoon.

In 2008, the Swan underwent a major conservation project, undertaken by our Council member Matthew Read. In 2010 he gave a fascinating talk on the subject for our Society, and recently he went back to Bowes to see that all was well, as reported in his blog ‘Friends Reunited’.

The story in the novel goes back and forth between the 19th century and the present. An Englishman commissions an automaton to be made in Germany. It’s inspired on Vaucanson’s famous digesting duck automaton, but somehow turns out as a (the?) swan – it’s all a bit unclear.

In modern London, a conservator in a fictional museum is given the task of restoring the by now dismantled automaton to working order. Her manager has set her this challenge, hoping it will take her mind off her grief over her lover’s sudden death.

Does it work as a piece of fiction? I am not sure. But what I am sure of is that there cannot be many novels that explicitly mention our journal:

'It was then, high on grief and rage, I stole two of Henry Brandling’s exercise books. What would happen if I was caught? Burn me alive, I didn’t care. I tucked them inside my copy of Antiquarian Horology, and walked straight past Security and out into the London street which was now, in late April, hotter than Bangkok' (p. 34).

If anyone knows another novel in which our journal occurs, please leave a comment!

Antiquarian horology in a graveyard

This post was written by David Rooney

Last weekend I went for a walk around King’s Cross and St Pancras, London. The area’s undergoing great change right now as part of a huge regeneration project. I was on the hunt for the mausoleum of one of the world’s greatest antiquarian collectors, Sir John Soane.

One of my most cherished places is the Soane museum in London, presented to the nation in 1833. Soane’s collection there is quite remarkable.

Sarcophagus in the basement? Check. Hogarths and Turners lining the walls? Check. The most exquisite juxtapositions and delightful sight-lines? Check, check, check. It’s a place like nowhere else. Go often!

My particular reason for viewing Soane’s tomb was that it was used by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott as inspiration for his famous red ‘K2’ telephone kiosk. I like things like that.

So far, so antiquarian. But where’s the horology? Well, I was on my way out of St Pancras Gardens, where Soane’s memorial sits, when I encountered a memorial sundial erected in 1879 by Baroness Burdett-Coutts, one of the great Victorian philanthropists and an early supporter of the British Horological Institute.

Isn’t it priceless? The sundial is inscribed, ‘tempus edax rerum’, or, ‘time is the devourer of all things’.

I was struck by the calm atmosphere of the gardens set amidst blocks of housing, the railway lines out of St Pancras, a hospital and the general bustle of London. I think the calmness came in part from the embedded memories in the memorials and inscriptions, which were often moving.

Time is the devourer of things. But we have found ways to use things in order to remember. Periodically, they might be reconfigured, as Soane’s tomb became a telephone kiosk. But that’s just our way of killing time.