The AHS Blog

A 68 minute weight – with verisimilitude!

This post was written by Jon Colombo

At West Dean College, first year clock students make a hoop and spur wall clock from scratch. As far as practicable we use techniques available to an eighteenth-century clockmaker. This gives the deepest understanding of the mechanics, aesthetics and the way historic clocks are put together. Verisimilitude is important, but not critical. When making driving weights, students usually use brass tube, topped, tailed and filled with lead. As a former archaeologist, I wanted more authenticity.

Examining a selection of old weights showed:

- The joints do not seem to be soldered. Under a microscope, often the seam is marked by a thin copper-coloured line, likely to be loss of zinc from the brass.

- The joints are not brazed. It is common for the skin to split along the joint. Were they brazed, failure here would be very rare.

- Often the lead has shrunk away from both sides and hanger, leaving a hollow tube running down into the weight.

- The bottoms are almost always domed.

The first two suggest a butt joint. The third that the lead is stuck to the skin. It could be just the filling holding the whole thing together. Cooling shrinkage cooling would pull the skin into compression, and explain the need for domed base. The logic was convincing; time to try it.

I cut a skin and domed base of thin brass sheet, tinned and wired them tightly together. I then embedded the shell in sand and poured in lead.

Manufacture is simple, quick, economic – sheet formed on bar, butt joint filed, wired up and ready to go; hanger made from old wood screw.

The results were pleasingly close to the originals. The lead bonds firmly to the walls, heating them enough for the outside to take on a copper colour. In cooling the lead pulls the joint tight and forms the right shrinkage patterns. When I cleaned the weight, the copper colour was often left in the now very tight butt joint.

If you fancy giving it a go, or are simply curious, http://westdeanconservation.com/2014/06/05/a-68-minute-weight-with-verisimilitude/ gives a bit more detail.

War time reflections

This post was written by James Nye

The June centenary of the Archduke’s assassination is behind us, though in July 1914 no one imagined a world war breaking out a month ahead (head to the LMA for a great new exhibition).

In May, my talk at Greenwich—‘Bang on Time’—focused on 1940s clockwork devices used for delaying explosions, and it seems quite a few of my blogs dwell on bombs and destruction. Today, I reflect on some horological titbits from the Great War.

For a start, patriotism (and then conscription) emptied out light engineering and clockmaking firms of their young workers.

Of the 450 staff at Smith & Sons (MA) Ltd, floated in July 1914, nearly 10 per cent were at the Front a month later.

Silent Electric’s Herbert Bowell confirmed to the authorities in March 1917 that all his employees had signed up in 1914.

His better-known brother George, by contrast, was a munitions worker—the path for many other craftsmen.

After the ‘Shell Crisis’ of May 1915, resources poured into shell and fuze-making capacity, with the result that millions were crafted, to be fired on the battlefields of Europe. Though military demand for chronometers and timekeepers of all sorts mounted rapidly, clock and watchmakers from Clerkenwell were packed off to the north-east to work in firms such as Vickers, to manufacture fuzes.

While the factory workers and the soldiers they supplied are long gone, their products endure.

A standard artillery fuze might delay firing the main charge by up to half a minute. Precise (and expensive) fuzes had a clockwork escapement (see video) while vast numbers were simply igniferous, though even then involving a dozen or more precisely machined parts.

These remarkable engineered brass mementos regularly emerge from the soil a century later, and will still strip down.

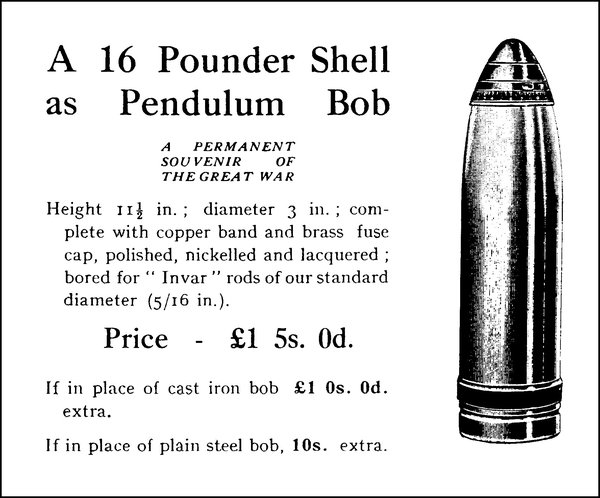

While surplus shell cases formed myriad household ephemera for years – Trench Art – another astonishing survivor was courtesy of the clock trade itself, in an idea from the irrepressible Frank Hope-Jones, who purchased 16-pounder shells (and fuzes), offering these as a pendulum bobs—a ‘souvenir’ of the Great War. What a blast!

Unreliable public clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

You only have to walk around in your own town to observe that of all the public clocks you pass by, only a few tell the correct time. Many show just any time, others have stopped working altogether.

Last year, a tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Guardian suggested that it was ‘time for a public clock tsar, with power to demand that owners restore their timepieces to reliable service’.

Here I learned of the existence of the blogspot Stoppedclocks, which invites us to ‘help find and fix all the stopped public clocks in Britain’. So if you have a particular gripe about a faulty clock in your area, you now know where to turn to.

There is, of course, nothing new under the sun. More than three centuries ago a correspondent to a London newspaper ventilated his gripe about the unreliability of public time-pieces.

It is quoted here, with the numbers referring to the map, as published in an article by Anthony Turner entitled ‘From sun and water to weights: public time devices from late Antiquity to the mid-seventeenth century’, published in Antiquarian Horology in March 2014.

![Details from John Roque, Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark…, 1747. The eastward route of the correspondent of the Athenian Mercury, and the nine numbered locations, from Covent Garden [1] to the Royal Exchange [9], are indicated in red (click on image to expand it)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/map-of-London2.width-600.jpg)

'I was in Covent Garden 1 when the clock struck two, when I came to Somerset-house 2 by that it wanted a quarter of two, when I came to St. Clements 3 it was half an hour past two, when I came to St. Dunstans 4 it wanted a quarter of two, by Mr. Knib’s Dyal in Fleet-street 5 it was just two, when I came to Ludgate 6 it was half an hour past one, when I came to Bow Church 7, it wanted a quarter of two, by the Dyal near Stocks Market 8 it was a quarter past two, and when I came to the Royal Exchange 9 it wanted a quarter of two: This I aver for a Truth, and desire to know how long I was walking from Covent Garden to the Royal Exchange ?'

(Quoted from The Athenian Mercury, vi no 4, query 7, 13 February 1692/93).