The AHS Blog

Horology in action

This post was written by David Thompson

Mechanical clocks turn up in the most unlikely situations.

When thinking of the Battle of Britain and the courage of the airman who flew Spitfires and Hurricane in defence of Britain in 1940, the humble clock does not immediately come to mind as playing a part in active service. However, selected aircraft in squadrons were fitted with a signalling device which allowed the controllers at strategic airfields to plot the position of fighter aircraft and so direct them to intercept approaching enemy aircraft.

The system used by the Royal Air Force was commonly known as 'Pipsqueak'.

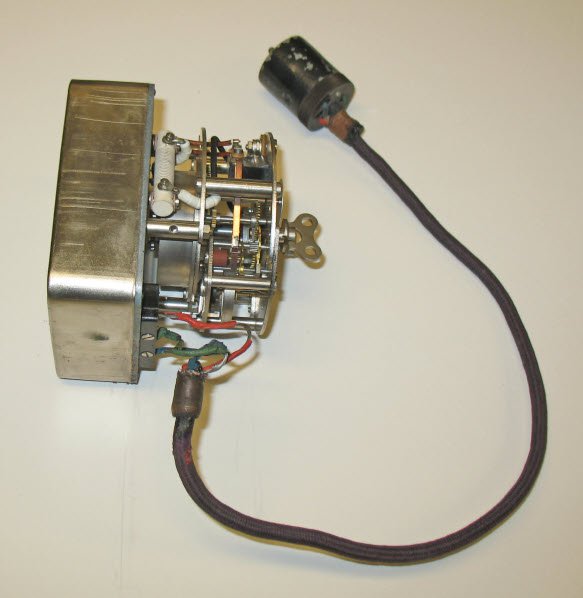

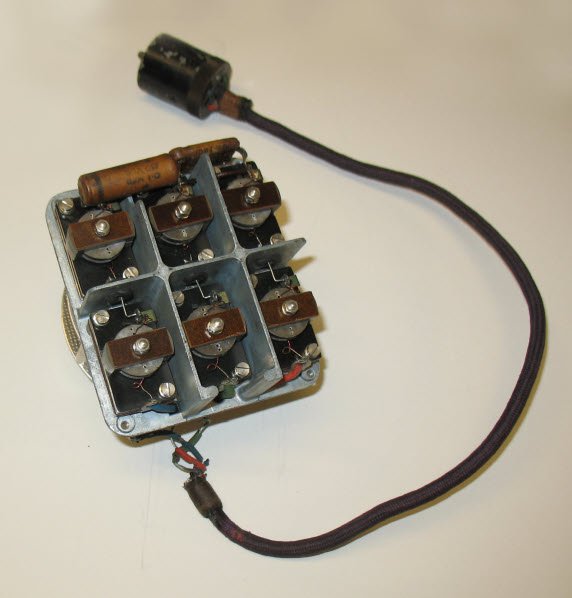

Fitted into the aeroplane behind the pilot’s seat was a Bakelite box containing a clockwork mechanism which would run for about five hours when fully wound. This was connected to an on-off switch located next to the pilot in the cockpit.

When switched on the aircraft radio would transmit a series of signals produced by electrical coils once per second for 14 seconds. The radio signal generated would then be received by the tracking station to enable the location of any particular group of aircraft to be located at any time. There is even a small heating coil inside to maintain the temperature to aid better timekeeping.

The system was normally used in two aircraft in the squadron. The clocks would be synchronised with the control tower and then when required the clock signals could be transmitted from the aircraft so that its location could be determined from the direction of the signal being received at a number of different receiving and transmitting stations. The information would then be transferred to the operation control centres so that aircraft could be directed to where they were needed to intercept the enemy.

Link to source of Spitfire image used above.

A book sale to remember

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Many of us who are captivated by the history of timekeeping have an equal interest in the historical literature on the subject; in fact, such is the fascination with antiquarian horology, that quite a few of us have more books than clocks and watches!

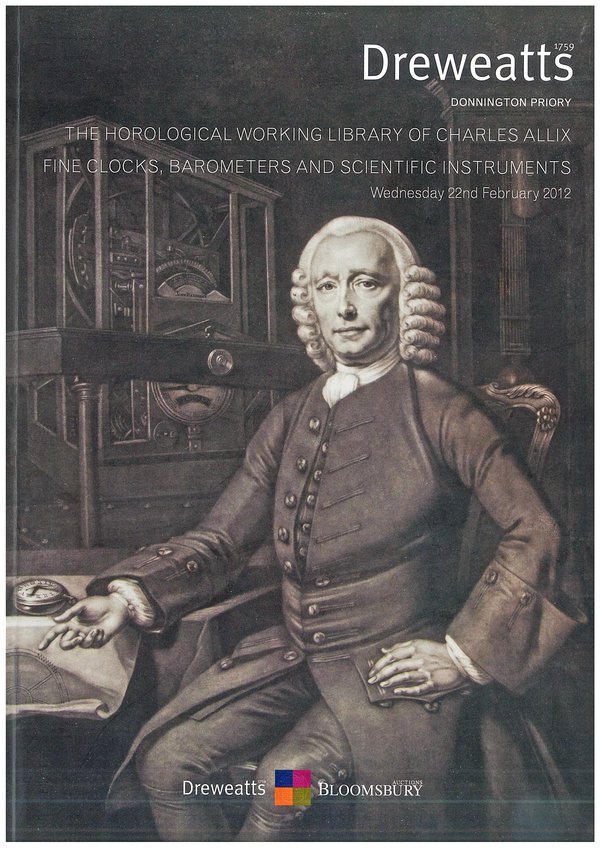

For these horological bibliophiles (don’t try saying that with your mouth full!), ‘the sale of the century’ took place last month (on 22nd February) when Dreweatts of Donnington sold the working library of the distinguished antiquarian horologist, Charles Allix.

Charles, who is now enjoying a well-earned retirement, amassed a very fine collection of books and ephemera, and with subjects ranging from turret clocks to watches, there was something for everyone.

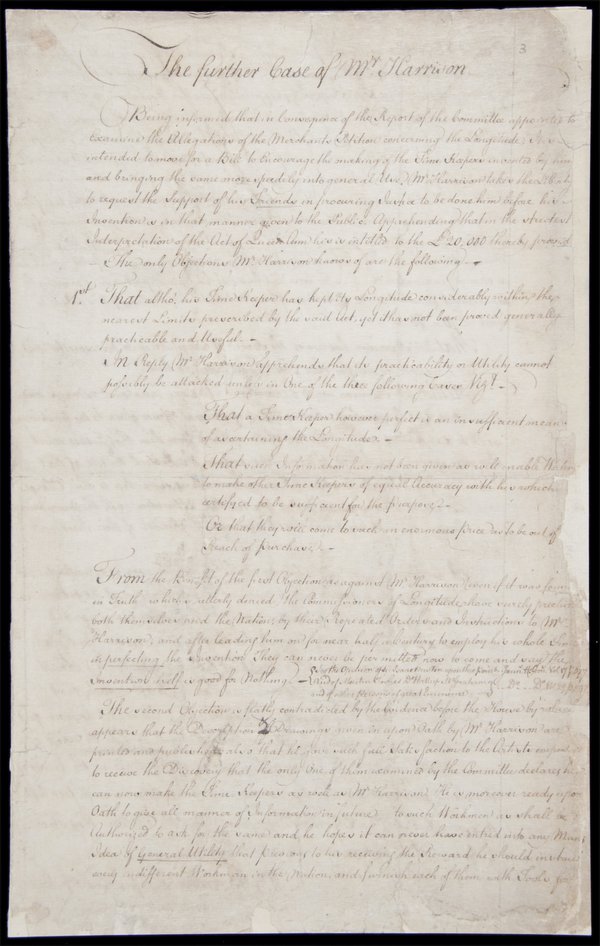

Undoubtedly the stars of the show were a small group of manuscripts which had belonged to the great John Harrison (1693-1776) and it was predictably these lots which brought the highest bids.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers hold the largest body of original Harrison manuscript material, and the Company were keen to add these, which were some of the very last Harrison-related documents out of safe captivity in museum collections.

The lots were hotly contested – some of the prices were a long way above upper estimates – and the horological world was reminded again of the enduring interest and importance of the Harrison story.

In the event, most were acquired by the Company (Charles Frodsham’s kindly doing the bidding on their behalf), and they are now safely secured for the future and available for research.

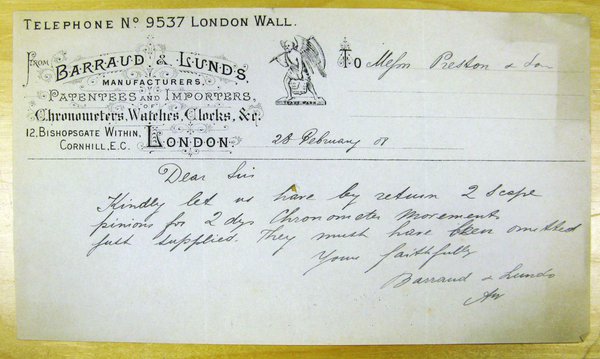

My own organisation, recently re-named Royal Museums Greenwich (after the Borough was granted Royal status) was also successful in acquiring some fascinating correspondence from the firm of Preston’s of Prescot, one of the most significant English manufacturers of rough movements for marine chronometers.

The extraordinary detail informing the day-to-day processes involved in making and supplying these movements to the finishing trade, will greatly enhance the research currently being carried out on the museum’s collection of marine chronometers.

This research is due to be published in a large and definitive catalogue The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich , due out in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the 300th anniversary of the famous Act of Parliament offering huge prizes for solutions to the problem of finding longitude at sea.

The smallest clockmaker’s workshop in the world

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

What I like about museums is the same thing I like about public parks. You can go in and be happy without having to worry about costs, upkeep and security, as private collectors or garden owners have to.

What’s more: entrance to many of the best museums is free. Deciding to walk in and have a look is just as easy as taking that walk in the park.

There are many museums with historic clocks and watches, and those in Great Britain are listed on the AHS website. There are enough to keep you busy for a long while.

If you are in the City of London, for example to see St Paul’s Cathedral, why not also take a look in the nearby Clockmakers’ Museum at Guildhall. Gathered in one ground-floor gallery you will find the treasures assembled over the years by the honourable Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. It was established in 1631 and is still active, which makes it the oldest surviving horological institution in the world.

Among my favourite showcases is the one filled with horological curiosities [Fig 1]. The object at the bottom is a model of a clockmakers’ workshop [Fig 2]. It was made around 1930 by the London antique dealer Percy Webster, who was Master of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1926 – they have a new Master every year!

It is indeed a curiosity, as it is not known why it was made, nor what period he intended to represent. But it’s fun to kneel down and look at this horological equivalent of a doll’s house. The only thing missing is the miniature clockmaker himself.