The AHS Blog

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ Time Machine: perpetual calendar or not?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

I am fascinated by gimmicks used by past watch manufacturers to make their products stand out in a crowded marketplace and this post is the first in a short series on some attention seeking watches that have piqued my interest.

This post takes a look the Wittnauer ‘2000’, a quirky automatic wrist watch from the 1970s.

It is a snazzy-looking chunk of a watch and is impressively big at 46mm across the case and crown; the dial does not disappoint with its day, date and complex-looking calendar information around two apertures at twelve and six o’clock.

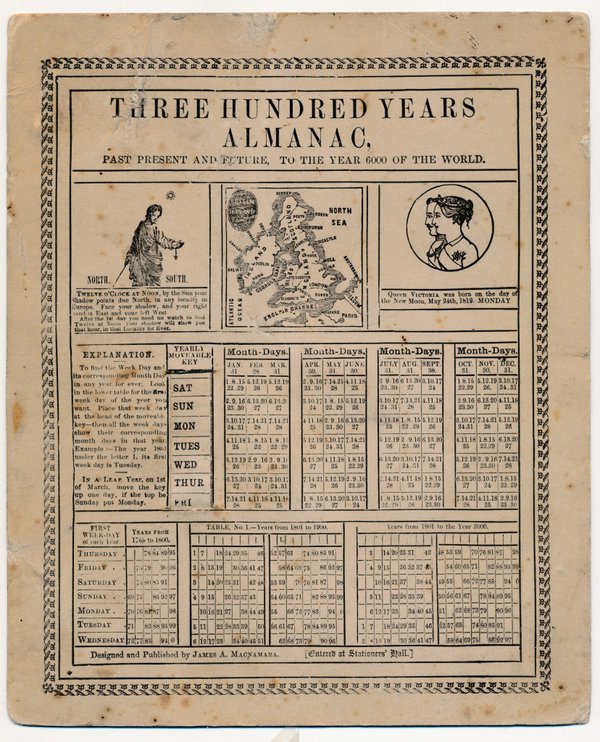

It was advertised in the early 1970s as a time machine with perpetual calendar, which is technically correct but arguably a little misleading.

The perpetual calendar is a celebrated complication prized by collectors of high-end wrist and pocket watches.

The intricate mechanism required to keep the calendar in step with the short months and leap years demands multiple precisely made components, is only found on the best watches and, unsurprisingly, its presence in a watch hikes the value substantially.

Stephen McDonnell’s recent innovative perpetual calendar design. Uploaded to Youtube by Quill and Pad.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ has a perpetual calendar, which does conform to the same definition.

The date display is a standard type, which must be manually advanced at the end of a short month. It is more normal for the calendar to be set using the crown, but why do that when you can have an extra button on the outside of the case? Instead of keeping the date in sync, it uses tables and a revolving scale to reckon the day of the week for a given date.

The mechanics of the design are very simple, the revolving disc has a contrate gear on its reverse, which is driven by a pinion attached to a second crown.

The years and days of the week are printed on the revolving disc and, as can be seen in the image, aligning the year with the month on the lower table (at six o’clock), places each day of the week above one of seven columns (at twelve o’clock) that contain the relevant days of the month.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ perpetual calendar employed an old and simple technology to allude to luxury. For a modest price it had bags of 70s style and, as with any self-respecting time machine, had buttons aplenty!

Winding the Caledonian Park turret clock

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

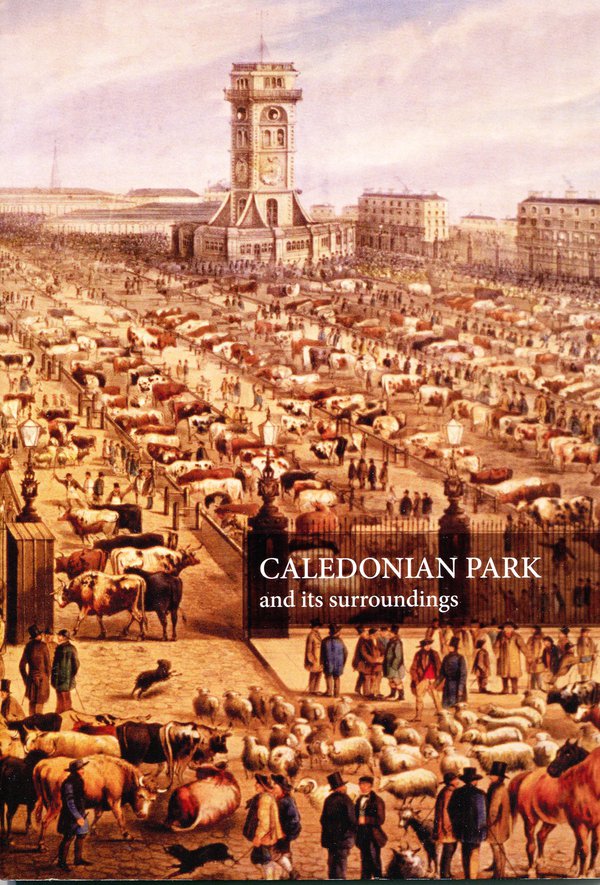

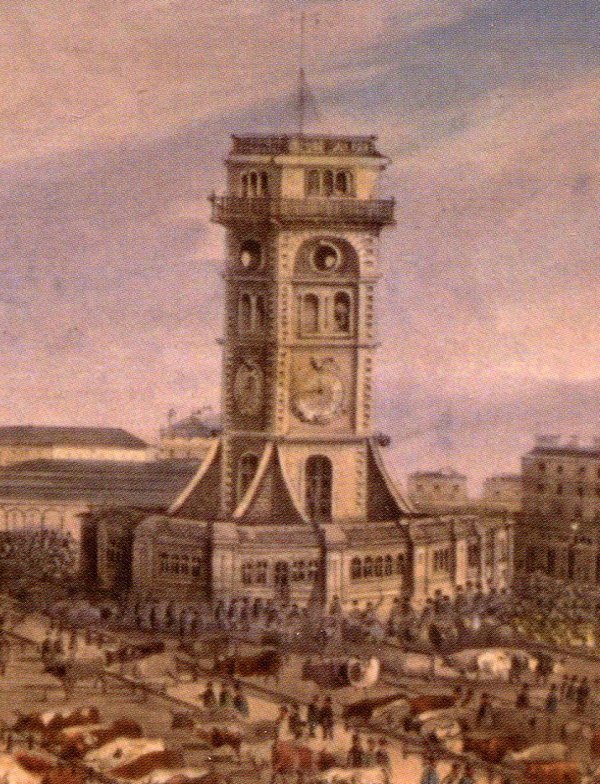

In Caledonian Park, in the London Borough of Islington, stands a distinctive 45 meter clock tower with four dials that can be seen from far away.

It was erected in the 1850s to serve as the command centre of the newly laid out Metropolitan Cattle Market, which had been created to replace the old more centrally located Smithfield Market. The tower is a Grade II listed building.

You can see the clock movement in this short videoclip:

Turret clock expert Chris McKay has recently published a facsimile reproduction of A List of Church, Turret and Musical Clocks. Manufactured by John Moore & Sons. 38 & 39, Clerkenwell Close, London, dated 1877.

For the year 1854 we find: ‘Islington, London Four 10-ft. 6-in. dials, chiming, for the Cattle Market.’

The chimes are no longer in operation, from what I understand at the insistence of nearby residents. But the clock is still running and showing the correct time.

During an open day last summer I had a chance to get into the tower, and to see the clock and enjoy the view from the balcony.

The organizers were looking to extend their group of volunteers for the weekly winding of the clock. I signed up and am on the rota now, so I regularly climb first a cast iron spiral staircase and then a series of steep ladders to get to the movement and pull up the heavy weight.

It’s a good physical exercise and a welcome hands-on experience for someone whose involvement with horology is normally limited to sitting at a desk putting together the quarterly journal of the AHS.

The Caledonian Park Friends Group have published a booklet with much information on the history of the market, which for a while also functioned as a flea market.

The cover shows the market in full swing, but the artist has made a bad job of representing the tower. If the dials were really as low as where he painted them, climbing up to wind the clock would be a lot easier!

Donation to the British Museum

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

I write with a foot in two allied camps: as a member of the AHS and a Curator of Horology at the British Museum.

In October last year the AHS Council generously donated sixteen interesting clocks, watches and horological tools to the BM collections. The items had in fact been at the BM since 1973, having been deposited on long-term loan when the AHS left its former London HQ.

This conversion to a donation consolidates that loan and upholds one of the core objectives of the AHS which is the support of public collections.

Let us look at three of the items.

Firstly, a lantern clock with centre verge pendulum by Johannes Kent of Congleton, Cheshire, late 17th century.

Lantern clocks with centre pendulum sometimes had 'angel wing' extensions to the side doors to accommodate the arc of pendulum. This clock does not have these, but the side doors (which seem to be later) do not interfere with the action of the pendulum.

Unusually for this time, the clock does not have Huygens’s endless winding system, but has a separate drive for each train.

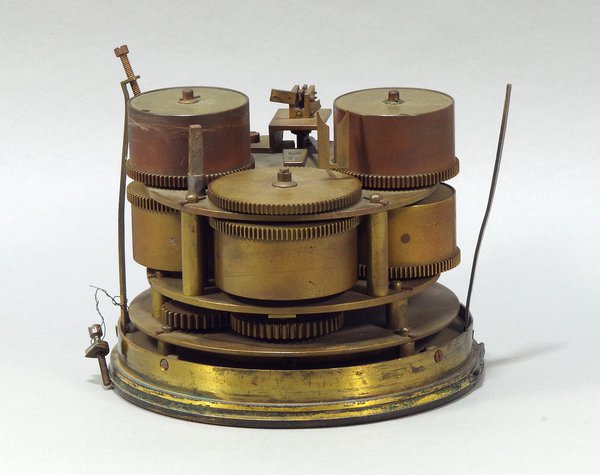

Next, an interesting year-going movement. This was probably housed in a slate or marble case, perhaps something like this.

The inscription on the dial is somewhat rubbed and not wholly legible, but it seems to be signed for Edward Watson of King Street, Cheapside, London (working 1815-63) who would have been the retailer for the clock.

The movement is stamped to show that it was made by Achille Brocot of Paris. Brocot invented this type of long duration movement in the mid-19th century, employing multiple mainsprings in going barrels to drive the clock.

The system has great advantages over using a single large mainspring to achieve a long duration. Smaller springs are easier to make and much easier to remove for maintenance. Also, if one of the five springs were to break it would cause far less damage to the clock than a recently-wound single spring with a year’s worth of driving energy being unleashed.

… and finally, an unusual and incredibly useful screwdriver. It has five slot heads at different orientations enabling access to those awkward screws, such as between the plates of a movement.

Right, I’m off to attend to a newly-installed longcase clock which has stopped – an in-situ adjustment of the back cock should do it..!

As with all items in the collections of the British Museum, these items are kept to be made accessible to all members of the public. An appointment to study them can be made by contacting the horological team at horological@britishmuseum.org or by telephone (020 7323 8395).