The AHS Blog

Stories of an everyday timepiece

This post was written by Andrew Hyatt

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. One of the things that interest me in horology as a student are the stories that timepieces can tell. Whilst the world changing events of John Harrison’s H1 through to H5 or the exciting life of Larcum Kendall’s K2 do make for fascinating reading, I am talking about the story every timepiece that I hope to end up servicing will tell me.

This story is not necessarily the emotional attachment that the owner undoubtedly has to the item. That can be interesting, but in taking apart one of my first clocks I found what I consider to be a much more interesting story.

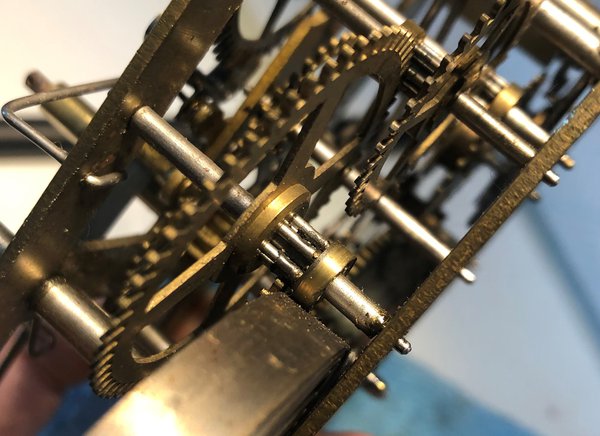

The clock shown below is a mass produced 2 train clock with a rack striking mechanism. I picked it up because I loved the art-deco style case and the unusually shaped dial.

It is clear that several other people also did as when I took the movement apart my initial observations found a couple of things, the first is that at some point the pendulum suspension spring has been replaced. Both the rod and the back cock have been bent to accommodate a new plastic topped spring shown below.

This made me a little worried about the rest of the mechanism with what appeared to be a quick fix to get the clock running again, but as I continued I found evidence of what may have been a more caring hand. The back cock also shows evidence of the escapement/crutch arbor pivot hole having been re-bushed with the finish almost invisible on the acting face. One of the click springs has also partially sheared, but then its been re-blued.

This tells the story of one or more people that got this clock running again and I am excited to add my name to that list, hopefully in a less noticeable way, as this clock continues its story.

Elizabeth Tower from construction to conservation

This post was written by Jane Desborough

On a cold, dark evening recently my spirits were lifted when I had the pleasure of listening to an online lecture on the conservation work that has been undertaken on the Elizabeth Tower at Westminster.

Presented by tour guide, Catherine, who is clearly very experienced in talking about the Tower, the clock and the bells, it was a really engaging and accessible gallop through the history and overview of the recent conservation works.

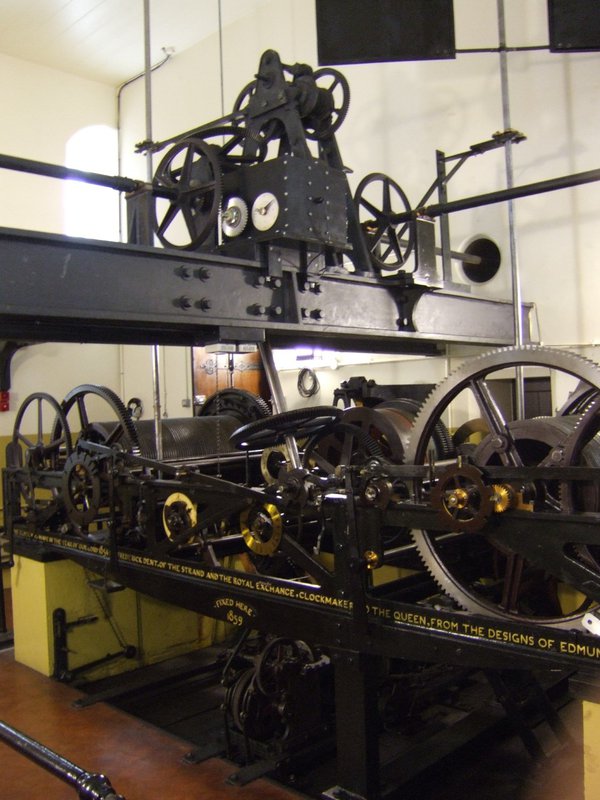

For fans of horology, there were no big surprises – most people know the story about the cracked bells and the key players ( Edmund Beckett Denison, Sir George Airy, Edward John Dent and Frederick Dent) involved in the design and making of the clock – but a couple of points stood out for me.

The first was the discovery that when the clock was finished in 1854, it had to wait for the rest of the tower to be complete before it could begin its public service – this was five years later in 1859.

The idea of a paused instrument – one that’s designed to move continuously – made me think that there must have been a lot of work needed to store it safely, maintain it in good condition and to set it going five years after its production. It was interesting to hear that those five years provided some time for experimentation with the escapement.

Another fascinating aspect of the talk was centred on the lamps required to light the dials at night. Recent conservation work has replaced all of the lamps with LEDs.

As a more efficient lamp, the LED will obviously be a good energy-saver. The change makes sense, but I couldn’t help being pleasantly surprised that the same changes being made at a small, household scale are also being made on a larger scale with our public buildings.

For me this talk was great because you can think you know a clock or a building, but there’s always something new to discover!

Opening my first clock

This post was written by Alexandra Verejanu

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. In the context of the lockdown I got pretty behind in my studies as we couldn’t go into the workshop. As I knew it would be helpful to see and touch a mechanism, I decided to buy some cheap old clocks. The clock I have 'played' with brought some interesting questions to my attention.

Firstly, I couldn’t take it out of the case, probably because it didn't seem to have been made to be serviced. I might have stumbled upon one of those old American clocks which were made to look fashionable in the house, but after a few years were discarded as uneconomical to repair. .

I looked closely and it was obvious someone has taken it out of its glued case using some aggressive methods, like bending the bell rod and cutting holes in the case. After two hours of struggling to carefully remove the mechanism from the case, I bent the bell rod and took it out.

Then, I examined the mechanism which was very oily. I knew excessive lubrication can do more harm than good, but I didn’t expect to see damage with the naked eye.

In the future I intend to change the damaged pieces, hopefully with some I will produce in the school workshop.

I decided not to take apart the mechanism just yet, as it was useful as a comparative item to the clocks I was presented with during online courses.

Considering this timepiece is not in its best shape, I might try to do some case work during the summer. I will not be able to fix the cuttings, but I’ll give it a good clean and maybe turn the case into an easy to open one.

This clock was very helpful during lockdown and helped me understand the mechanics of a clock. It truly helped me connect and mesh information from various sources which I was not able to understand.

Special thanks to my teacher Mathew Porton, for taking his time to answer all my questions and making sure I will be safe when I disassemble the mechanism and work on it.