The AHS Blog

An eighteenth-century wind-up

This post was written by James Nye

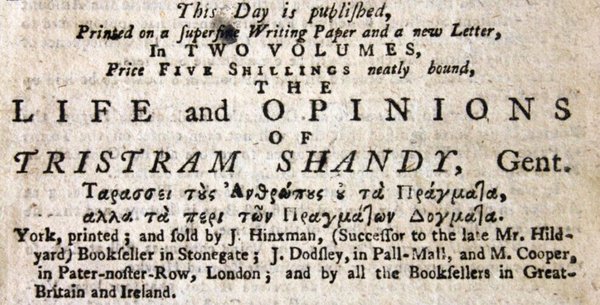

Perhaps an AHS blog post is an unusual place to find literary criticism, but the recent death of Dr Bill Linnard, a much-loved horological scholar, calls to mind his treatment of a risqué horological joke at the opening of Laurence Sterne’s Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (see Horological Journal April 2014, pp. 174–5).

The narrator, Tristram, describes his father as a man of unshakeable and timely habits, winding ‘a large house-clock, which we had standing on the back-stairs head’ on a monthly basis, and, we are to infer, making love to Mrs Shandy on a like schedule. At the moment of Tristram’s conception, the earth does not move as expected: ‘Pray my Dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?’

The book seemingly met with general outrage owing to its saucy content. As Linnard noted, the Clockmakers’ Company and the wider horological trade were apparently among the most offended, a small group of them publishing The Clockmakers Outcry Against the Author of the Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (J. Burd, London 1760).

In this pamphlet we learn that sex-workers in London had come up with a new opening gambit. ‘Nay, the common expression of street-walkers is “Sir, will you have your clock wound-up?”’ As a result, clocks had become taboo and orders were cancelled, much to the chagrin of the trade. Timepieces were now viewed ‘as obscene lumber exciting to acts of carnality’.

Bill Linnard described the pamphlet as a spoof, but many conclude that Laurence Sterne himself was the author, engaged in a tradition of puffery by publishing criticism of one’s own work – there being, after all, no such thing as bad publicity. We can be confident the clockmaking trade did not actually suffer at all, and there is, rather regrettably in retrospect, no other known reference to gentlemen being asked if they wanted their clock winding.

OK. We can see through Sterne’s elaborate artifice in stirring up further interest in his own work, but what was his inspiration? This is the question we clockmakers need answering. Why might Sterne have delved into the world of clockery, and on such a bawdy basis?

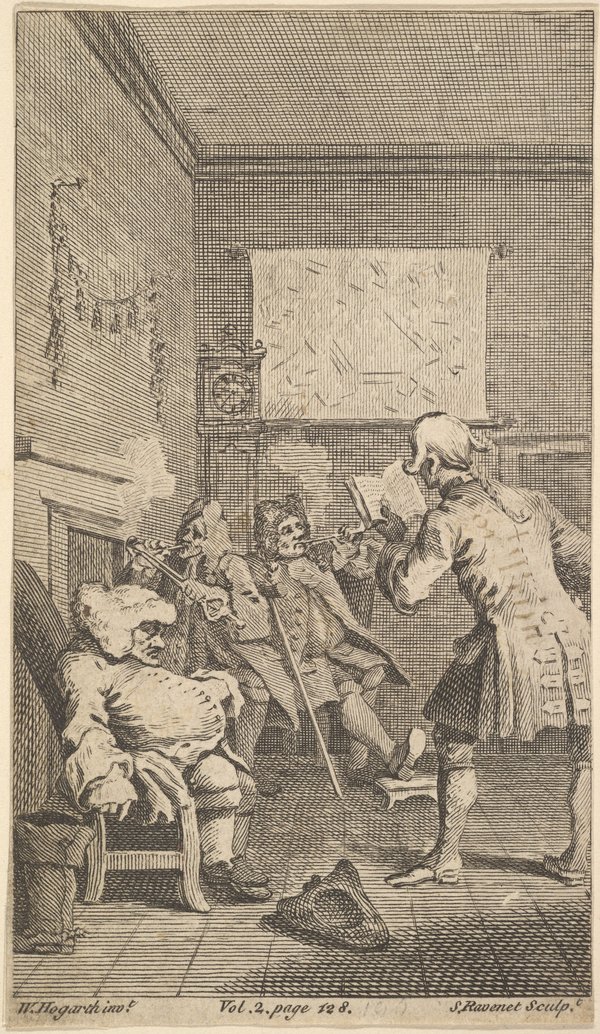

A possible answer lies in his friendship with William Hogarth, who provided illustrations for Tristram Shandy. As Patricia Fara amply demonstrated in her AHS London Lecture on ‘Hogarth: Time’s Artist’, in January 2023, the imagery and symbolism of clocks were subsumed throughout Hogarth’s work. Clocks were part of an attempt at rationalisation and control, but also stood for the frailty of humanity. Hogarth was also no stranger to conjuring images of the seedier side of life.

A month-going clock was no common item in the mid-eighteenth century – it was an expensive luxury, or a natural accessory for an enlightened gentleman, a sort of exquisite machine to bring order amid potential chaos. Someone close to Sterne had one, we have to assume. And since it was in his nature to satirise or parody such attempts to impose control, the clockmakers came in for some unlucky wind-up humour.

Playing card packing pieces

This post was written by Tobias Birch

As some of you might know I am passionate about Thomas Mudge. So in June 2023 I was delighted to be invited by the curator of horology at the British Museum, Oliver Cooke, along with esteemed horologists Andrew King and Jonathan Betts, to look at two Mudge clocks, the Lunar Mudge and the Polwarth Mudge.

Jonathan was researching for his upcoming talk to the AHS, 'The Technical Legacy of Thomas Mudge'. While inspecting the ebonised case of the Lunar Mudge, a case that is, I believe, the beginnings of the three pad top style case table clocks you see in the second half of the eighteenth century, I decided to remove the seatboard. You never know what you might find!

On removing the seatboard, made more involved as one had to first remove a brass carrying handle, the effort was soon rewarded.

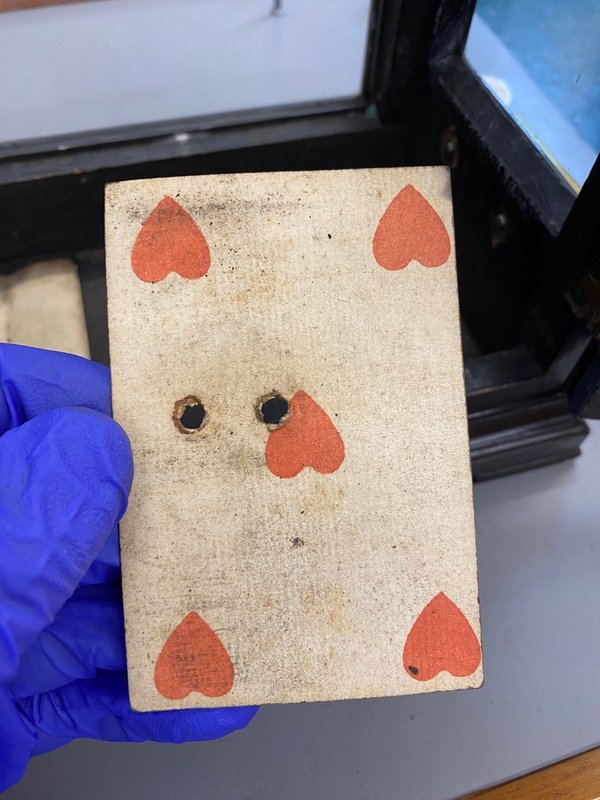

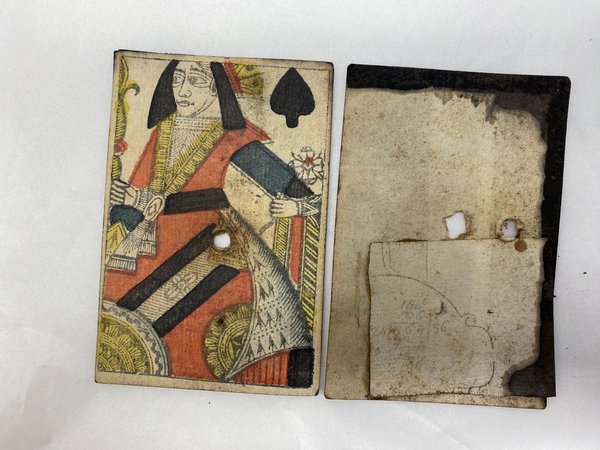

To all our surprise, hidden beneath the seatboard I found some playing cards, and not your everyday, free in Christmas crackers playing cards. They were a well preserved hand-painted Queen of spades and a five of hearts. Most likely eighteenth century playing cards.

The cards were placed under the seatboard, as convenient packing pieces to raise the movement slightly, probably when the clock was originally made in the 1750s. After photography I placed them carefully back in the position from where they came.

This was the first time in over 30 years of working on clocks that I had seen playing cards used in this way, and I didn't expect to see it again. Yet, less than a year later, while working in my own workshop on a Thomas Mudge and William Dutton table clock of the three pad top style that I mentioned earlier, made around twenty years later than the Lunar Mudge, I once again did my usual practice of removing the seatboard. This was more easily done this time, as there was no handle to take off first.

You have no doubt guessed what I found.

Here the cards were folded over and held in place with small round head brass nails. The left card was too indistinct to make out the suit, the card on the right is a two of spades. Again, hand painted on similar colour card as the Lunar Mudge cards.

I would be interested to hear from anyone that has found similar playing cards placed under seatboards of table clocks. Perhaps there was an avid card player in the Mudge workshops and they used cards from incomplete decks they had lying around? Or perhaps they used cards from a deck that had proved unlucky and they no longer wanted to play with?

We will never know, but I liked the link back to an individual, long gone, whose work survives and who, if I were to somehow meet, would, I imagine, have plenty to talk about.