The AHS Blog

Time symbols in cemeteries

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My wife and I like to visit cemeteries. To some this may seem a morbid pastime, but we value their tranquillity, and appreciate them as a kind of open-air museums where we see how our ancestors commemorated their dead.

In Lisbon is the enormous hillside Cemitério do Alto de São João (Height of St. John Cemetery), overlooking the river Tagus. Opened in 1833, this vast necropolis is mostly filled with family tombs and mausoleums, lining what they call ‘ruas’, ‘streets’.

On gravestones and funerary monuments, you often see the hourglass as an emblem of mortality, a symbol of the passing of time. Often there are wings at the sides, reminding us that time flies and eventually will run out for all of us.

The Cemitério do Alto de São João contains many examples of these winged hourglasses, often in combination with other symbols of death, such as the scythe of Father Time, an inverted torch symbolising the extinction of the flame of life, or a skull and crossed bones.

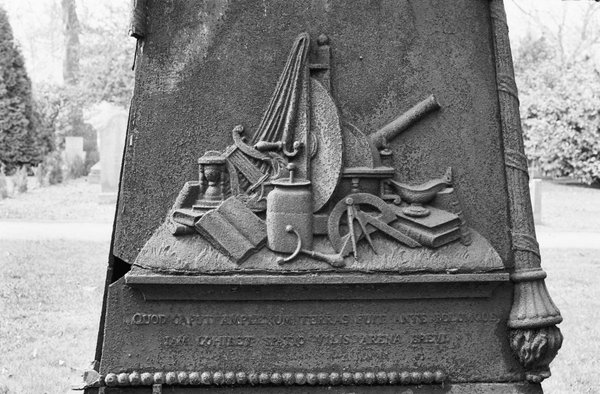

An hourglass is also depicted on a cast-iron funerary monument erected in 1832 on a Dutch cemetery, together with an oil lamp, symbol of eternal life, seen standing on a book on the right. The lamp is also shown prominently on a design drawing for this monument and there are also inverted torches on the monument, as can be seen here.

The hourglass and the lamp are mixed in with an elaborate ensemble of scientific instruments (a single-plate electrostatic generator, with a Leiden jar and a discharger in front, a telescope, and three drawing instruments), which commemorate that the deceased man had a strong interest in the natural sciences, and owned his own collection of scientific instruments.

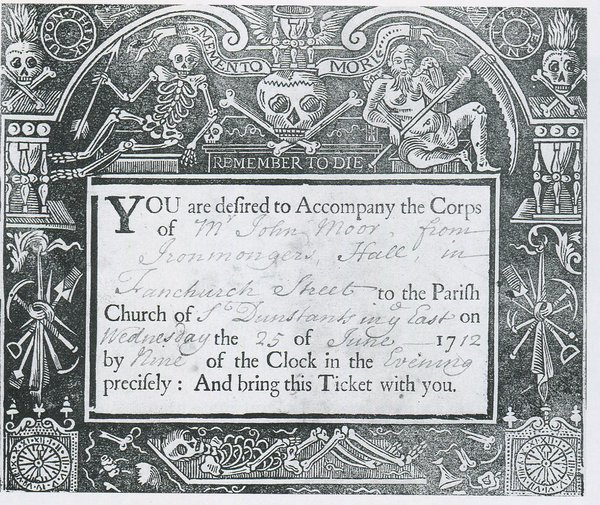

On a printed invitation to attend a funeral, dated 1712, we see three hour glasses, one of them winged. But there are also, in the bottom corners, two clocks, another reminder of the passing of time.

On our visits to cemeteries, we have only once found a clock depicted on a gravestone, where it was part of the instrumentation of the deceased, the German astronomer C. L. C. Rümker (1788–1862). This was also in Lisbon, in the British Cemetery, and it was shown in an earlier blog, Clocks in Lisbon.

But in the Cemitério do Alto de São João we found something we had never seen anywhere else: the depiction of a clock dial.

The hands are in the classic ‘10 past 10’ position, and the dial is accompanied with a sobering text that translates as ‘The hours go by / the days go by / the years go by / and our lives go by’.

And as if that were not clear enough, at the bottom is again the winged hourglass.

Unless otherwise stated, photos by Jade de Clercq.

Who was Master Humphrey?

This post was written by James Nye

Sometimes I'm asked about my lifelong obsession with clocks and what on earth I see in them – or perhaps what they say to me.

In reply, I'll comment about their longevity and the fact they tend to last longer than people. I'll observe that they tick out the lives of those around them – that they are observers in whom the events they witness become inextricably bound up.

And I'll say that sometimes, when we are researching or writing about those subjects, our clocks help us along with helpful nudges and hints.

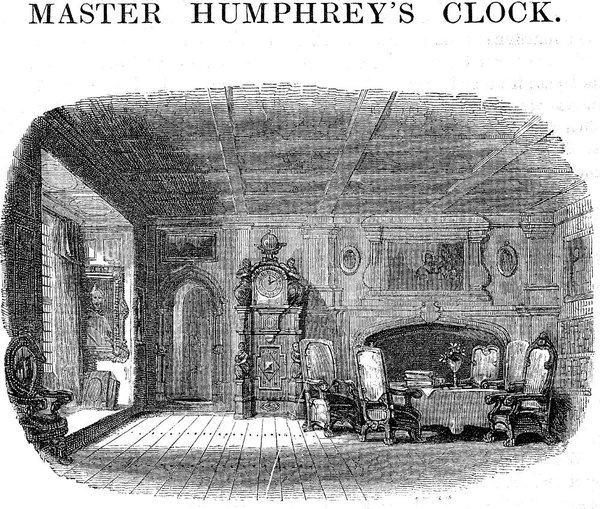

It pleases me to know that Charles Dickens had something of the same sense. In Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840), the eponymous timepiece is imbued with the same timeless and comforting qualities.

Discussing the work with a friend, Dickens describes a quaint old character who has a great affection for a clock:

"He has got accustomed to its voice, and come to consider it as the voice of a friend […] its striking in the night has seemed like an assurance to him that it was still a cheerful watcher at his chamber door […] its face seemed to have something of welcome in its dusty features, and to relax from its grimness when he looked at it from his chimney corner."

Not very practically, Dickens had the notion that the trunk of the clock could be a safe repository for the manuscripts of a club that would meet to read to each other. He says:

"I mean to tell how that he has kept his old manuscripts in the old, dark, deep, silent closet where the weights are, and taken them thence to read (mixing up his enjoyments with some notion of the clock), and how, when the club came to be formed, they, by reason of their punctuality, and his regard for this dumb servant, took their name from it."

The Horological Journal of October 1912 (available online to AHS members) carries a pleasing account of Dickens’s inspiration.

In 1837, Dickens spent several weeks in Barnard Castle, Yorkshire, researching school conditions for Nicholas Nickleby. While there, he encountered a clockmaker named William Humphreys.

In 1828, Humphreys had acquired an ornamental seventeenth-century Dutch longcase clock with a worn-out movement. The following year, having fitted it with a new mechanism, he installed it in a niche to the right-hand side of his shop door.

This was the real "Mr Humphreys' clock," consulted occasionally by Dickens on his local journeys. He came to know not just the clockmaker himself but his son, Master Humphreys. In Dickens's mind, "Humphreys" became "Humphrey," and thus was born the inspiration of his 1840 work.

And as I type, I am accompanied by a comforting tick from a shelf just beside me. If I wait a few more minutes, I will be reminded of the hour...