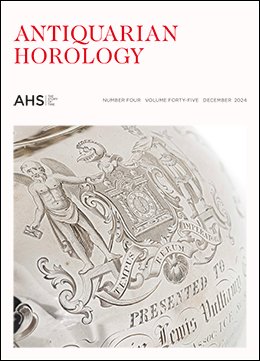

Volume 45, Issue 4 December 2024

On the front cover: Detail of a silver kettle made by Edward John and Willliam Barnard, presented by the Clockmaker’s Company to Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy. It is one of the objects in the exhibition Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy: A Champion of British Craftsmanship, which is in the Clockmakers’ Museum in London until 2 November 2025. Photo: Science Museum Group / The Clockmakers’ Museum. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum.

This issue contains the following articles:

James Cox: manufacturer and merchant – Part 1

by Roger Smith (pages 463-481)

Summary: This article has been developed from a lecture given at the University of Neuchâtel on 28 May 2013. It is in two parts, with Part 1 covering the background to Cox’s involvement in the export of clocks and watches to the ‘East Indies’ – the term commonly applied by eighteenth-century Europeans to an enormous region of South- and East Asia which included India, Indonesia and China. It also looks at the production of larger articles like clocks and automata in Cox’s own workshop and by his known collaborators. Part 2 will consider the production of jewellery and other small articles by Cox, before discussing the more restricted mercantile role that he adopted towards the end of his career.

John Harrison (1693–1776): a legacy of invention and engineering. Part 2

by Ann McBroom (pages 482-504)

Summary: John ‘Longitude’ Harrison has been the subject of multiple excellent publications detailing his life and horological achievements, some only recently confirmed. The current paper is designed as a supplement. Part I explored the genealogy of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren and offers a broad summary of their lives. Part 2 looks in greater depth at the inventive and engineering skills many displayed, and explores what happened to JLH’s writings and instruments as they passed through these first few generations.

Reassessment of the painted clock dials of Thomas Pyke Sr & Jr of Bridgwater and an introduction to the painted clock dials of Cox of Taunton, Somerset. Part 2

by Nial Woodford (pages 505–518)

Summary: The first part of this article reassessed the painted clock dials of the Thomas Pyke foundry of Bridgwater, Somerset. This second part discusses the little-known Cox foundry at Taunton, a town situated some eleven miles southwest of Bridgwater. In the period 1821–1840 it bought in blanks for finishing, and manufactured painted iron dials, nineteen examples of which are presented here.

No. 67 Fleet Street, after Thomas Tompion – and some nineteenth-century plans

by James Nye (pages 519-529)

Summary: In the absence of other information, one might expect Thomas Tompion’s final premises to be fronted by his own shop at street level. Yet we have long known he shared his building. Evans, Carter & Wright discussed furniture-maker Braem, saddler Tesmond, and haberdasher Clutterbuck as some examples of co-tenants, but no detailed consideration has previously been given to what the passer-by might have seen at the street-level frontage of 67 Fleet Street. Further, little attention has been focussed on how much space was available for new-making and servicing of clocks and watches when Tompion and Graham were residents. This article discusses some hitherto unremarked plans of the premises from the mid-nineteenth century, which probably offer our best clues as to the square footage and footprint of the property. In the main it explores the use of the building – certainly the shop-front – over the 120 years or so after Graham left, until it was finally demolished, and highlights the different uses to which the internal space may have been put, for retail and for bench work.

Mozart’s watches

by Peter de Clercq (pages 530-540)

Summary: From the abundant surviving correspondence of the Mozart family, we learn that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) owned five gold watches. The letters shed an interesting light on the way he acquired them, and on his own thoughts about them. We know very little of what became of them after his death; only two watches said to have belonged to him are known, and for both the provenance can be doubted. In one letter Mozart refers to the current fashion for men to wear two watches, and this is picked up as a side-theme in this article. (Read this article here)

Clocks at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

by Bob Frishman (pages 541-545)

‘Unfreezing Time #20’ by Patricia Fara (pages 546-547) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

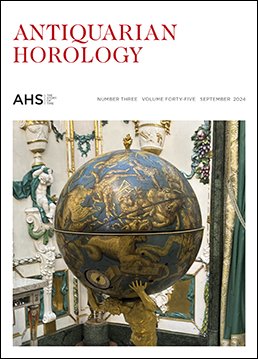

Volume 45, Issue 3 September 2024

On the front cover: Close-up of a sculpture representing Hercules carrying a celestial globe with a clock signed on the dial by Abraham-Louis Breguet. It is on display in the Royal Palace in Madrid. (Photo Keith Scobie-Youngs). It was seen during the Society’s Study Tour to Spain, which is reported in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

John Harrison (1693–1776): a legacy of invention and engineering. Part 1

by Ann McBroom (pages 318–348)

Summary: John ‘Longitude’ Harrison has been the subject of multiple excellent publications detailing his life and horological achievements, some only recently confirmed. The current paper is designed as a supplement: Part I explores the genealogy of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren and offers a broad summary of their lives. Part 2 looks in greater depth at the inventive and engineering skills many displayed, and explores what happened to JLH’s writings and instruments as they passed through these first few generations.

Italian grande-sonnerie whizzing work striking

by John A Robey (pages 349–362)

Summary: This article discusses the specifically Italian system of whizzing-work that produces grande-sonnerie using only one striking train. After describing the principles of whizzing-work, four clocks are considered that all employ this idiosyncratic system. While the basic method is the same for the first three clocks, which have two-hands, they show regional variations and different arrangements to produce similar results. The fourth clock is likely to be the earliest one described here, and differs considerably in the layout of its striking-work. All four clocks have different escapements and dials, two of the dials being very unusual, possibly unique.

Reassessment of the painted clock dials of Thomas Pyke Sr & Jr of Bridgwater and an introduction to the painted clock dials of Cox of Taunton, Somerset. Part 1

by Nial Woodford (pages 363–379)

Summary: This is the first part of a two-part treatise reassessing the painted clock dials of the Thomas Pyke foundry of Bridgwater, Somerset and the introduction of a believable link with a number of painted dials emanating from the little-known Cox foundry of Taunton. The review of Pyke dials is based on communications to the author post publication of an article concerning Thomas Pyke’s pewter enhanced painted dials published in the June and September 2015 editions of the journal.

AHS Study Tour to Spain

(pages 412-428)

Summary: A richly illustrated report of the recent tour to Spain. (Read this article here)

Note: on the AHS Grant of Arms (pages 395–397)

‘Unfreezing Time #19’ by Patricia Fara (pages 380-381) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

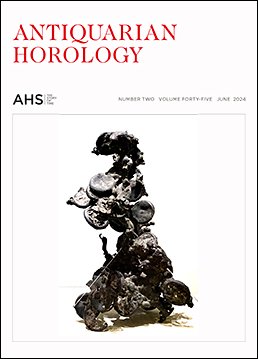

Volume 45, Issue 2 June 2024

On the front cover: Seiko Museum fusion of customer watches burned and melted during the 1923 great earthquake. Dug from the ruins of the Seikosha shop. Photo Bob Frishman.

For details see his article Horology in Tokyo in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City – an exhibition review

by Ian White (pages 166-175)

Summary: Zimingzhong: Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City was the title of an exhibition held at the Science Museum in London from 1 February to 2 June 2024. It was initially planned for 2020, but was postponed because of the pandemic. It brought to London an unprecedented exposure of the great skills of London clockmaking aimed at a totally different market from that of Europe. The exhibits came from the Palace Museum in Beijing, which has the largest collection of clocks in the world, a collection made by the Emperor Ch’ien-lung, who reigned from 1736 to 1796

Dismantling the ‘East School’ – Edward East and the clock trade in seventeenth-century London

by Richard Newton (pages 176-196)

Summary: The article summarises a London Lecture given by the author on 13 July 2023 and suggests that Edward East was acting principally as a retailer of clocks manufactured by others. By examining the movements of clocks signed by East we can see that they correspond with the work of John Hilderson, Ahasuerus Fromanteel, William Clement, Samuel Knibb and others. Further groups of movements from a common source but different signatures can also be identified and suggestions as to the maker are made. (Read this article here)

John Hilderson (?–1665): An update

by James Nye (pages 197-205)

Summary: To date, our knowledge of John Hilderson has best been brought together in the substantial piece of work by Anthony Weston in the June 2000 edition of Antiquarian Horology. Richard Newton’s recent work revealing Edward East’s sources for movements confirmed John Hilderson as the source for East’s pendulum clock movements in the first half of the 1660s (see Richard’s article in this journal). The recent discovery of the 1666 inventory of Hilderson’s house and workshop prompts a re-evaluation of our knowledge of the details of this important early maker.

Watertight pocket watches known as explorers’ watches, retailed by Herbert Blockley & Co., 41 Duke Street, St James, London

by Simon Davidson (pages 206-216)

Summary: This paper examines the retailing by Herbert Blockley & Co. of watertight pocket watches manufactured by Usher & Cole, known as explorers’ watches, to meet the need for accurate timekeeping in humid conditions. It met a need amongst the public travelling or working particularly in polar or tropical or latitudes, and is also illustrated by the Royal Geographical Society adopting this case model for supply to their sponsored expeditions. The paper highlights the output and the two models of watertight watches that Herbert Blockley retailed over the period 1890 to 1917.

Travel journals and the history of horology

by Peter de Clercq (pages 217-235)

Summary: Travel journals contain valuable information for historians, and this includes those who have a special interest in the history of horology. This article, an edited version of the Dingwall-Beloe Lecture delivered at the British Museum on 17 November 2022, offers horological information gleaned from the travel journals written by the Frenchman Balthasar de Monconys (1608–1665), the Englishman Philip Skippon (1641–1691) and the German Heinrich Sander (1754–1782). Neither of them had practical experience or personal involvement with clocks and watches, and this article concludes with a discussion of similar documents recording travels undertaken by two men who were actively involved in the trade: the Swiss clockmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721–1790) and the English clockmaker James Upjohn (1722–1794).

Picture Gallery: An unrecorded early pendulum clock

by Richard Newman (pages 236-240)

Summary: The clock illustrated and discussed in this article was made in 1666 by Johann Koch who was the clockmaker to King Charles XI of Sweden.

Museum profile: Horology in Tokyo

by Bob Frishman (pages 241-246)

Summary: This article presents the Daimyo Japanese Clock Museum, the National Museum of Nature and Science and the Seiko Museum.

Berthoud 1759: a bibliographical note

by Anthony Turner (pages 247-250)

Summary: Examination of several copies of Berthoud’s first publication L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres : à l’usage de ceux qui n’ont aucune connoissance d’horlogerie has allowed the true second edition to be distinguished from a pirate edition that was hitherto thought to be that.

‘Unfreezing Time #18’ by Patricia Fara (pages 260-261) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

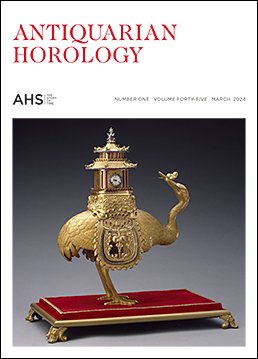

Volume 45, Issue 1 March 2024

On the front cover: More than twenty clockwork treasures collected by Chinese emperors have travelled from the Palace Museum in Beijing to be displayed in the Science Museum, London. The exhibition ‘Zimingzhong: Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City’ runs from 1 February to 2 June 2024. The clock shown here was produced by James Cox, and incorporates parts made in China. Photo © The Palace Museum

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Ellicott’s Dissertation and the Spanish Connection. With an introduction and analysis’

by Paul Tuck (pages 19–43)

Summary: An undated document written by John Ellicott (1706–1772) was in response to a request from an unknown ‘Noble Personage’ concerning the possibility of improvement in the regular going of watches. The original manuscript was lost and only known as a Spanish translation in the Biblioteca Real, Madrid. In 1957 this was transcribed by Junquera and published in a Spanish journal of horology, causing it to be recognized by Malcolm Gardner as being Ellicott’s faded original which he had acquired from the library of Percy Webster. Its contents are now revealed and give an insight into the state of watchmaking at a time when compared with the accuracy of pendulum clocks, the lack of such precision in pocket watches was beginning to be seriously questioned.

‘James or Jacob Hassenius, a clock- and watchmaker in London and Moscow’

by Keith Stella (pages 45–62)

Summary: This article examines the life and works of a Russian-born clockmaker, James (or Jacob) Hassenius, who lived and worked in London from around 1682 to 1698 and who, following the visit of Peter the Great to London in that year, then left England to work for the Tsar in Moscow as a clock- and watchmaker. Several London longcase and bracket clocks and at least two watches, all signed ‘Jacobus Hassenius’, are known to survive. As a result of some research papers written by a former colleague of the curator of clocks at The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, we are now able to trace what became of James Hassenius once he left England. The known clocks and watches signed by Hassenius while working in London are briefly catalogued in the Appendix to this article. (Read this article here)

‘Experimenting with the pendulum: the work of Tito Livio Burattini (1617–1681)’

by Augustin Gomand (pages 63–87)

Summary: The main studies related to the first pendulum clocks focus on the prototypes invented by Christiaan Huygens, described in Horologium in 1658 and in Horologium Oscillatorium in 1673, as well as on the commercial models made by Salomon Coster and reproduced by various clockmakers in Europe. However, others tried to apply the pendulum to clocks in parallel to Huygens’s work or inspired by it. The clocks resulting from this are interesting because they were conceived with an experimental and scientific purpose, to experiment with the pendulum oscillator and to test its regularity; they may present atypical layouts which deviate from the models proposed by Huygens. Several brief descriptions of such experimental clocks designed by the Italian-Polish engineer Tito Livio Burattini (1617–1681) offer an opportunity to analyze his original constructions and to understand how they fit into the scientific context of the time and are linked to the personality of this inventor. This article is part of the Simon Le Noir Project.

‘Grande sonnerie monumental clocks of Detouche and Houdin (c1855). Part 2, The great clock of the Conservatoire‘

by Denis Roegel (pages 88–96)

Summary: In the early 1850s, the clockmakers Constantin-Louis Detouche (1810–1889) and Jacques-François Houdin (1784–1860) developed a new system of ‘grande sonnerie’ for public clocks. This two-part article aims at describing this little known system. Part 1 described a new striking work patent by Detouche and Houdin, and its implementation on a clock around 1855, but that clock was unfortunately later transformed and the multiple countwheels are no longer extant. In the second part, we describe the Detouche clock of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers in Paris, installed in 1863 on the grand entrance staircase, where it is still located.

An Horologion horologically illustrated

by Anthony Turner (pages 97–103)

Summary: An horologion is a book prescribing prayers and adorations to be observed throughout the day by the faithful. The use of clock images in a Jesuit version from 1691 displays how the spiritual use of the clock metaphor continued to be employed.

‘Unfreezing Time #17’ by Patricia Fara (pages 104–106) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

Volume 44, Issue 4 December 2023

On the front cover: We don’t have records of the names of the men who wound the Great Clock of Westminster in the early days, but they have left their marks in the form of footprints worn into the ground around the clock. Photo Simon Camper.

‘Big Ben’ features prominently in the section AHS News in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Clockmaking and practical mathematics in the provinces of Britain and France, 1500–1800’

by Anthony Turner (pages 461–487)

Summary: Clock- and watch-making in Early Modern France and Britain was not exclusively an urban activity. In towns and villages throughout the provinces time-measurement by clocks, watches or sundials was required, while elaborate astronomical clocks acted as mechanical almanacs and advanced popular education. At the same time, such items displayed their makers’ skills, opening a path to income and reputation. This article is based on the AHS London lecture delivered on 9 March 2023. AHS members can watch a recording of the lecture in the website member area.

‘The Bull family of clockmakers Part 2. Randolph Bull (c. 1557–1617)’

by Adrian A Finch,Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages 488–506)

Summary: Continued from Antiquarian Horology, September 2023, 339–352. The second part of this article continues the story of the Bull family with Randolph Bull, who was John Bull’s brother and apprentice. Randolph Bull was trained in John’s workshop probably by Michael Nouwen but he worked with Bartholomew Newsam in the early 1580s and established himself independently in St Gregory by St Paul’s parish in 1582. He was appointed as royal clock-keeper in 1589 on the death of his brother. Randolph Bull’s workshop produced the earliest pocket watch bearing an Englishman’s name and trained a significant part of the watch and clock-making community of the period. His eldest son Cuthbert was introduced to the Goldsmiths’ Company in 1605 but died soon afterwards. Randolph tried to bring his son Emmanuel to take over his business, but Emmanuel displeased his father and was replaced in Randolph’s succession by Anthony Risby and Francis Foreman. Randolph died in 1617; the community trained by the Bulls would in the fullness of time become a central part of the workforce that established the Clockmakers’ Company in 1631.

‘Grande sonnerie monumental clocks of Detouche and Houdin (c1855). Part 1’

by Denis Roegel (pages 507–516)

Summary: In the early 1850s, the clockmakers Constantin-Louis Detouche (1810–1889) and Jacques-François Houdin (1783–1860) developed a new system of ‘grande sonnerie’ for public clocks. This article aims at describing this little known system.

‘John Donegan’s watch factory in Ireland’

by David Boles (pages 517–528)

Summary: In ‘The Irish Museum of Time, Waterford, Ireland’, published in the December 2022 journal, mention was made of a contemporary description of John Donegan’s watch factory, published in the Dublin Weekly Nation newspaper edition of 1 May 1858. This article offers a transcription of this interesting document, with a short introduction and some explanatory insertions.. (Read this article here)

‘Stephen Rimbault (1711–86)’

by James Nye (pages 529–537)

Summary: When the Seven Dials Trust recently decided to press ahead with erecting a plaque in Monmouth Street to commemorate Stephen Rimbault, the AHS was asked to verify his dates. What might be thought to be a trivially easy enquiry revealed that no biographical summary for this well-known maker had been undertaken previously. The following notes address this deficiency, and correct some misinformation that is regularly repeated, particularly with regard to working dates.

‘Picture Gallery: Three coach watches’

by Artemis Yagou (pages 538–544)

In this Picture Gallery we illustrate three objects from the Timekeeping collection of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, that, because of their size, may be classified as coach watches.

‘Unfreezing Time #16’ by Patricia Fara (pages 545–547) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 3 September 2023

The front cover shows the clock tower in Padua. Photo Paul Tuck.

The section AHS News in this issue contains an extensive and richly illustrated report of this year’s AHS Study Tour to Italy.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘The life and watches of William Anthony (1764/68–1844/47). Part 2, his watches’

by Ian White (pages 322–338)

‘The Bull family of clockmakers Part 1. John Bull (c. 1535–1589)’

by Adrian A Finch, Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages 339–352)

Summary: The earliest English clock- and watch-makers came to prominence in London in the late Tudor period. One of the key families in early London clockmaking was the Bull family, several of whom were clockmakers or mathematical instrument-makers of note. This article describes the first member of the family: John Bull, a mathematical instrument-maker. We show that John was primarily a goldsmith working in jewellery who recognised the potential of the mathematical instrument trade. He employed Dutch engravers and watchmakers, including Michael Nouwen, to produce items that were sold from a workshop in the newly-built Royal Exchange. Nouwen trained Randolph Bull in John’s workshop and we consider this a key moment in the development of the London horology trade. John was appointed as royal clock-keeper, presumably after the death of Bartholomew Newsam in 1587, the first London guild member to hold the post. He worked for the Crown through two of the most eventful years in British history, serving in the royal entourage at the time of the Spanish Armada, but died only a few years later in 1589. John Bull’s workshop is the historical nexus point as we trace the training of many of the clockmakers of Stuart London back in time.

‘ ‘Forever addicted to the mechanical’– Rudolf Kaftan and the Vienna Clock Museum’

by Tabea Rude (pages 353–368)

Summary: The Vienna Clock Museum was founded in 1917 in the middle of the First World War. Its nucleus was formed from the collection of a single collector, Rudolf Kaftan (1870–1961), who would shape the museum’s fate and character for the next forty-four years. This article, based closely on the Harrison Lecture delivered to the Clockmakers Company in September 2022, charts the evolution and development of the museum in tandem with examining some facets of Rudolf Kaftan’s life.

‘The conservation treatment of a refracting telescope on a universal equatorial mount c. 1741, signed Hindley, YORK’

by Timothy M. Hughes and Matthew Read (pages 369–376)

Summary: Henry Hindley (1701–1771), clockmaker, watchmaker and maker of scientific instruments, was born in Wigan and worked in York from 1731 until his death. Hindley was the maker of the world’s first equatorially-mounted telescope, which can now be seen in Burton Constable Hall, East Yorkshire. The Hindley telescope is the subject of this article; the conservation ethos and methods described in the full report are relevant to the conservation of a wide range of historic dynamic objects, including clocks and watches. The communication of conservation processes is also, we believe, important to the wider understanding of time-finding and time-telling collections. (Read this article here)

‘From oil painting to enamel watch case: a latter day Metamorphosis’

by Anthony Turner (pages 377–380)

Summary: Combined use of documents and surviving paintings permits the process by which an original scene was transferred from a painting to a watch case to be illustrated, and confirms an attribution that has been contested.

There is also a 2-page note ‘BEHIND THE STARS — a free app using interactive versions of astronomical instruments to comprehend the heavens’, by Frederik Nehm & Michael Korey, and an announcement of a Special Sale of R.T. Gould ephemera for AHS Charitable Funds.

‘Unfreezing Time #15’ by Patricia Fara (pages 392–393) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 2 June 2023

The front cover shows the sailor jack prior to re-installation. Date thought to be c. 1950, photographer unknown. Winter family collection.

For more information see the article on Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire, in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘The ring-watch of Emperor Charles V’

by Víctor Pérez Álvarez (pages 169–178)

Summary: The miniaturization process in horology began in the fifteenth century and reached its zenith in the first half of the sixteenth century, when the earliest known ring-watches with striking mechanism were made.

The first watches of this type were very rare objects of prestige and often presented as diplomatic gifts. Charles V, the Dukes of Urbino, the Pope, and Suleiman the Magnificent were probably the first owners of ring-watches. In this article we publish four letters dated 1538 about Charles V’s ring-watch which shed further light on the history of these objects.

‘Summe Dyrections towards the makinge of a smale watche, of brasse’ – A guide to watchmaking techniques in the seventeenth century

by David Thompson (pages 179–206)

Summary: It was not until the end of the seventeenth century that books were published to explain how clocks and watches actually worked. An anonymous manuscript among the Evelyn Papers in the British Library, which pre-dates those publications, describes in some detail how a watch was made. This article discusses the possible authorship and the contents of this manuscript, and offers an annotated transcription.

‘The life and watches of William Anthony (1764/68–1844/47). Part 1, his life’

by Ian White (pages 207–222)

Summary: William Anthony is not well known today, but his watchmaking career c.1790-1805 was conducted with flair and great originality. He made a significant fortune exporting his watches to China, and spent the rest of his life losing it. His life outside watchmaking was centred around the complex inter-relationships between his sister Elizabeth, the chronometer makers Grimalde & Johnson, the chemist John Huskisson, and Jane Luson, a wealthy widow.

‘Peter Litherland’s patent watches and their successors. A fine-grained history of rack lever watch production’,

by Michael Edidin (pages 223–230)

Summary: Taking a close look at the production and distribution of watches with Litherland’s patent escapement, I argue from the evidence of existing watches that Litherland did not license his patents, as is often stated. Rather, in the 13-year lifetime of the patents, the Litherland shop produced and fitted rack lever escapements for watches signed by others, including Robert Roskell. Using counts of existing rack levers, I also show that Liverpool (and London) production of rack lever watches did not expand until after the Litherland patents had expired. Rack lever production declined after other new escapements, notably Massey’s, were developed, though it persisted well into the era of detached lever escapements. (Read this article here)

‘Coming home: a tavern clock by John Dewe of Southwark, active 1733–1764’

by Martin Gatto (pages 231–236)

Summary: This article traces the history of a tavern clock, made around 1735 by the London maker John Dewe, from its appearance at an exhibition in 1949 to its repatriation from Australia in 2022; its history between c. 1735 and 1949 is unknown. It was then restored, and the treatment is discussed in some detail.

‘Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire: its history, context and conservation. Part 2. Jacob Winter – his later life and legacy 1865 to 1904’

by Steve and Darlah Thomas (pages 237-249) [continued from Antiquarian Horology March 2023, pages 91–100]

‘Unfreezing Time #14’ by Patricia Fara (pages 250–251) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 1 March 2023

The front cover shows a detail of a rear view of jacks and bells, showing fixings, from Sir John Bennett’s shopfront on Cheapside, London, re-erected at the Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan, USA in 1930. Photo © Mark Frank, 2018. For more information see the article on Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire, in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Prototype lantern clocks. Part 2: Newly discovered clocks’

by John Robey (pages 23–33)

‘Two precision clocks by William Nicholson’

by Jonathan Betts (pages 34–42)

Summary: This article describes the two known clocks signed by natural philosopher and scientific journalist William Nicholson (1753–1815). For a short summary of the life and work of this significant figure of the Enlightenment, see the Notes from the Librarian in this issue. (Read this article here)

‘An early demonstration of the spiral balance spring by Isaac Thuret’

by Rory McEvoy (pages 43–55)

Summary: In 2009, an unusual seventeenth-century table clock by Parisian clockmaker Isaac Thuret came to light in a French auction room. The unique shape of the case and empty holes on the movement plates strongly suggested that the clock had originally been made to demonstrate the then-new technology of the spiral balance spring. Through study of the clock, its restoration, seventeenth century sources, and recent scholarship, the article presents the dispute over patent rights to the spiral balance spring and opens a discussion on methodologies for dating religieuse clocks of the 1670s.

‘Daniel Quare (1648–1724): Yorkshireman, activist, Quaker horologist and businessman’

by Ann McBroom (pages 56–81)

Summary: Excellent accounts already exist of Daniel Quare’s horological legacy; 1, 2, 3 this paper is intended as a supplement. A painstaking search for a birth record for Daniel in Somerset, where he reportedly was raised, yielded nothing. 4 The evidence presented here is that he was a Yorkshireman, baptised Daniell Quaer at All Saints Wistow on 1 January 1649, the son of Robart Quaer. 5 My hope is that this will unlock new information about Quare’s early life and where and with whom he trained. Daniel Quare was a life-long activist. He worked tirelessly to achieve full toleration for Quakers, but his activism was far broader and included efforts to combat societal injustices in Britain and overseas. The current paper considers how, as a Quaker, he may have navigated his personal and business options.

‘The Lepaute tower clock of the future King Louis XVIII in Versailles (1780)’

by Denis Roegel (pages 82–90)

Summary: The clock described in this article is one of the earliest known tower clocks made by Lepaute, and the oldest such clock known with a pendulum length adjustment. It was installed in 1780 in a private mansion in Versailles owned by the future King Louis XVIII. It is in storage in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Strasbourg.

‘Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire: its history, context and conservation. Part 1: Jacob Winter 1865 to 1904’

by Steve and Darlah Thomas (pages 91–100)

Summary:Jacob Winter (1865-1935) was a first-generation watch, clock and jewellery retailer who began trading in Stockport around 1890 and whose business continued for a century. His shopfront was adorned with a projecting clock and three automata which chimed ting-tang quarters and struck the hours. Intended to draw public attention to the business, the daily displays did just that and became the town’s major attraction. What inspiration lay behind this? We will consider the possibility that sight of John Bennett’s emporium on London’s Cheapside inspired a young boy, and the coincidences of location and selection of clockmaker which came into play. We look at two clocks made thirty years apart to perform similar tasks and at the recent efforts to conserve one clock’s place in the life of a northern town.

‘A sphygmochronograph for registering the pulse’

by Thomas Schraven (pages 101–105)

Summary: An ongoing hunt for unusual short-time measurement devices by the Jaquet firm led to the discovery of an early clockwork item for recording the human pulse. This article describes its origins, development and operation.

‘Unfreezing Time #13’ by Patricia Fara (pages 106–107) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 43, Issue 4 December 2022

The front cover shows the serpent-head figure on the Lavra Monastery tower clock, one of the five tower clocks on the Athos peninsula in Greece, which are presented in the first article in this issue. Photo Spiridion Azzopardi.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘The Athos clock strike locking system Part 2: The five tower clocks found to be fitted with the system’

by Spiridion Azzopardi (pages 463–479)

‘Jonathan Paine: ‘Inventor of the illuminating dials’ Part 2 – ‘there is a great deal of screeching and squalling in the neighbourhood’

by James Nye (pages 480–494)

Summary: In the first part of this article, we focussed on Paine’s contribution towards the widespread adoption of illuminated public clock dials. This second part will cover other development work in turret clocks, and the details of his house style. It also explores the family history, and uncovers more of the wild world of nineteenth-century Bloomsbury, before reaching some conclusions and discussing Paine’s legacy.

‘Henry Sully, RÈGLE ARTIFICIELLE DU TEM(P)S – 1714 Vienna, 1717 and 1737 Paris’

by Robert St-Louis (pages 495–508)

Summary: In 1714, while living in Vienna, London-trained English clockmaker Henry Sully wrote and published the most influential horological book, in French, of the early eighteenth century. This article compares and discusses the different editions of this ground-breaking book, and provides translations of original texts by the author. Other written works by Sully, actual and planned, are also briefly described.

‘The Savage family legacy’

by Andrew Blagg (pages 509–520)

Summary: The article ‘Unravelling the history of George Savage’, published in the September 2021 issue of Antiquarian Horology, suggested that conflicting dates and locations in George Savage’s horological history were most likely caused by confusing different people in generations of the same family named George. This follow-up article examines the innovations in watch design attributed to George (II), (III) and family. Although links between individual family members and credits are mentioned, the main goal is to explore the work of an innovative family business, especially their important part in lever escapement development

‘Prototype lantern clocks. Part 1: The inspiration for the first lantern clocks and the Harvey workshop’

by John A. Robey (pages 521–529)

Summary: For many years it has been surmised that there must have been experimental and prototype clocks made before the earliest-known lantern clock appeared in its fully developed form shortly after 1604. The recent discovery of an early prototype, a slightly later fragment and a much altered dial-less clock has enabled the evolution of the first English domestic clocks to be reevaluated. Part 1 considers the background, the development of the lantern clock based on Flemish examples, and the first English makers of these clocks. Part 2 discusses in detail the newly discovered clocks, especially their unusual technical and constructional features, that enable the chronology of these experimental clocks to be established.

‘Making a luxury clock in late eighteenth-century Paris’

by Anthony Turner (pages 530–534)

Summary: A clock sold at auction in 2020, made in the later 1780s, was the product of four leading craftsmen: founder Jean-Baptiste Osmond, clockmaker Jean-Antoine Lépine, enameller Joseph Coteau and cabinet-maker Balthazar Lieutaud. (Read this article here)

‘Thomas Tompion 271. A case and movement reunited after more than 200 years apart’

by Richard Newton (pages 535–540)

Summary: Following their recent appearance on the market, it has been possible to reunite the movement of Tompion 271, an example of the smallest and rarest variant of Tompion’s phase II table clocks, with its original case.

‘Some aircraft clocks’

by Terence Camerer Cuss (pages 541–544)

Summary: The elapsed time clock, introduced in 1952, helped pilots with the landing process and contributed to airport safety. Another step towards overall safety was the introduction of aircraft flight recorder systems which were made mandatory in 1965. All the information collated by the recorder was set against a time signal produced by the pilot’s clock. Camerer Cuss & Co participated in both these developments.

Museum profile: ‘The Irish Museum of Time, Waterford, Ireland’

by David Boles (pages 545–553)

Summary: The Irish Museum of Time opened in Waterford on 14 June 2021 and is Ireland’s National Horological Museum. Waterford is located in the ‘sunny southeast’ of Ireland, just two hours by motorway or train from Dublin, and is Ireland’s oldest city.

‘Unfreezing Time #12’ by Patricia Fara (pages 258-259) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 43, Issue 3 September 2022

The front cover shows a detail from the dial of a longcase clock by Francis Henderson at Gosford House in East Lothian, Scotland. Photo James Nye. It is one of many clocks and watches seen during the highly successful AHS Study Tour to Scotland in May. For an illustrated report of the tour, see pages 413–26 in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘Leonardo da Vinci’s spring-driven clocks. Part 2’

by Dietrich Matthes (pages 317–326)

‘Illustrations of weight-driven clocks in some early printed books’

by Marisa Addomine (pages 327–335)

Summary: The representation of weight-driven clocks in early printed books is an interesting but relatively little explored topic. In this article an intriguing relationship between clocks, dice, oracular games and Renaissance books is introduced.

‘The Athos clock strike locking system. Part 1: Introduction and description of the locking mechanism’

by Spiridion Azzopardi (pages 336–344)

Summary: The author first visited Mount Athos in Greece in the year 2000 with a quest to explore its horological past. Since then, he has engaged in the restoration and conservation of many crown wheel and verge lantern clocks with short pendulums, as well as verge and foliot tower clocks. These projects offered an opportunity to study, document and research these clocks. This paper describes two discoveries and their significance. The first is an unknown and novel clock strike locking mechanism that was discovered on verge and foliot tower clocks at five monasteries. The other was that comparisons drawn between these five clocks have led to these two conclusions: (a) that they all originated from the same workshop and (b) that they were made on Mount Athos.

‘Jonathan Paine: ‘Inventor of the illuminating dials’. Part 1 – ‘the bells pealed merrily, and the people gave repeated cheers’

by James Nye (pp. 345–361)

Summary: Jonathan Purchis Paine (1784–1843) is best known as the maker of a series of turret clocks of fine quality, installed across the UK from the mid-1820s to the early 1840s. On the setting dials of some of those clocks, Paine added references to his wider work for Royal locations, the Office of Works and the General Post Office. He received two Silver Medals from the Society of Arts: one for a system of back-illuminated public clock dials and the other for an improved version of the Graham dead-beat escapement. Paine’s illuminated dials paved the way for the widespread adoption of the opal-glass dials with which we are familiar in public clocks. Clocks broadly corresponding to his ‘house style’ continued to be made by Elisha Tucker into the 1870s, and perhaps later. This article describes Paine’s life, the lively part of London where he was based – with a somewhat dysfunctional family – and assesses his contribution.

‘Benjamin Martin’s ‘Table clock upon a new construction’ ’

by Guy Boney Q.C. (pages 362–373)

Summary: In 1770, Benjamin Martin (1704/5–82) published a tract describing a table clock ‘upon a new construction’. The author has established that in total five examples of this clock are currently known to exist, including one which he acquired in 1968, and discusses and illustrates in this article. (Read this article here)

‘Materials expertise and networks: The case of Johann Conrad Fischer (1773–1854)’

by Artemis Yagou (pages 374–386)

Summary: The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries constituted a transitional period when new, dynamic forces of industrialisation were unfolding all over Europe. At the same time, this was a period of increased physical mobility, in which portable clocks and watches were highly sought after. Watchmaking depended on the interactions and interrelations of many different domains and practices, including the production of steel, a material crucial for making reliable springs and other watch parts. Johann Conrad Fischer (1773–1854), a metallurgist from Schaffhausen, Switzerland, provided quality steel to Swiss, French and English clock- and watchmakers. Fischer’s case illuminates aspects of the wider technical system surrounding watchmaking..

‘Unfreezing Time #11’ by Patricia Fara (pages 258-259) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 43, Issue 2 June 2022

The front cover shows a detail from the portrait of a woman holding a clock, which is the subject of the Picture Gallery in this issue. The photo was kindly supplied by the Tomassso Brothers Gallery, Leeds. The painting is now in the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘Bartholomew Newsam, c. 1530–1587’

by Adrian A Finch, Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages174-196)

Summary: This article chronicles the life and works of the English clockmaker Bartholomew Newsam, bringing contemporary documentary evidence and his extant pieces to understand more fully his background and upbringing, and how these influenced his professional life. He came from Yorkshire roots and his brother William was an important locksmith in York. He first appears in 1565 renting part of the Somerset House complex in the Strand, by which time he may already have been a Crown employee. He inherited his brother’s business in 1569 and then took over from Nicholas Oursian as keeper of the Royal Clocks around the latter’s death in 1575. His spring-driven clocks and other mathematical instruments are characterised by French design but Dutch or German styles of engraving, hinting that he employed Dutch engravers who flocked to England in the 1560s. His business trained his cousin John Newsam (who became established in St Clement Danes) and we infer that he employed Randolph Bull. He died in 1587 and his estate became the subject of a dispute amongst his family. Newsam was a pivotal figure in English horology. Prior to Newsam, the most important figures in London clockmaking were foreign, invited to court to fill a vacuum in expertise. Newsam was the first English manufacturer of spring-driven clocks and his pieces are similar to those of contemporary French makers. Newsam’s era prepared the way for a golden age in English clock and watch manufacture such that London began to develop as a world centre for the technology.

‘Leonardo da Vinci’s spring-driven clocks. Part 1’

by Dietrich Matthes (pages 197-207)

Summary: This article analyses Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings relating to spring-driven clocks including the associated texts based on recent transcriptions. This allows gaining insights into the fore-front of spring-driven clock-making technology in the late fifteenth century. It is being discussed how the challenges of the then still rather new technology were tackled and how the visionary artist developed ideas that were implemented during the following decades and centuries. To this end, interpretations of several of his mechanisms that were not discussed in the context of horology so far are given. Leonardo’s description of spring-making is confirmed by sixteenth-century clocks; differences to eighteenth-century practices are discussed.

‘Scrutinizing Huygens’s Figura drawing’

by Mart van Duijn, Ben Hordijk, Rob Memel and Jef Schaeps (pages 208-213)

Summary: After the publication of the article ‘Salomon Coster, the clockmaker of Christiaan Huygens’ in this journal, the authors decided to have the enigmatic Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657-drawing examined by the Leiden University Libraries. The investigation revealed that the Figura drawing had been made for the printing of the image in Huygens’s Horologium, published in 1658

‘The Priors: a successful British watch brand for the Ottoman market’

by Luigi Petrucci (pages 214-221)

Summary:In the second half of the eighteenth century, George Prior created what is arguably the most successful British brand for the Ottoman market. This article is about the four main actors involved during the 113 years of the brand’s existence from 1765 to 1878, namely George Prior (watchmaker, Turkey merchant and esquire of Halse, Somerset and Sydenham, Kent), his son Edward Prior (Turkey merchant and esquire of Halse, Somerset), William Chambers (watchmaker) and his son George Chambers (watch manufacturer). (Read this article here)

‘The rise and fall of Samuel Wilkes, Birmingham dialmaker’

by John A. Robey (pages 222-240)

Summary: Samuel Wilkes was one of the largest of the later generation of clock-dial manufacturers in Birmingham in the nineteenth century. He initially worked with his father John Wilkes, who had previously traded as Wilkes & Baker, before Samuel took over the business. While his dials are regarded as not particularly special, he had an interesting life. He married into a family of important engineers and manufacturers, moved into property speculation, climbed up the social ladder, lived in a large house in a then fashionable northern suburb, and amassed a collection of Old Master paintings. After his almost inevitable bankruptcy in 1850 he was last recorded as a metal dealer. This article looks at his life and examples of the dials made by Wilkes & Baker and Samuel Wilkes, and also at the economics of the japanning and clock-dial trades.

‘‘The feminisation of the horological craft’. Gisela Eibuschitz and Kitty Herz, forgotten Jewish pioneer horologists’

by Gerhard Milchram and Tabea Rude (pages 241-253)

Summary: The Vienna City Museum Group’s restitution programme and accompanying systematic research led to the discovery of several Jewish clock- and watchmaking businesses, which in turn led to unravelling the stories of the first two traditionally trained female clock- and watchmakers documented in Vienna. Both Gisela Eibuschitz (1883–1942) and Kitty Herz (1898–?) came from Jewish clock- and watchmaking families.

‘The Simon Le Noir Project’

by Augustin Gomand (pages 254)

A one-page note.

Picture Gallery: 'Woman holding a clock'

by Anthony Turner (pages 255-257)

‘Unfreezing Time #10’ by Patricia Fara (pages 258-259) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 43, Issue 1 March 2022

The front cover shows the centre of the dial of Alexander Cumming’s own barograph clock, dated 1766. Photo © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum. The clock, together with four other surviving barograph clocks made by Cumming, is discussed in this issue by Jonathan Betts. His article and the article by Charlotte Rostek are based on lectures given at the AHS Annual Meeting held at Greenwich in May 2019.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘Huygens’s pendulum clock invention — conclusive proof of its first printed image’

by Sebastian Whitestone (pages 25-37)

Summary: Narrative histories of Huygens’s invention continue to be wide of the mark. Over a century ago, Coster’s simple domestic timepiece was put at the centre of the story, completely missing Huygens’s aim of Longitude chronometry. Other accounts portray him labouring with a modified balance-wheel clock when he was testing a seconds-indicating regulator. Placing his Horologium model of 1658 as his first developed design lands on the other side of the target, out by a year-and-a-half. Fortunately, there is a 1657 image that sets the record straight, but such is the resilience of muddle, that a proof of its date is now necessary.

‘The Third Earl of Bute’s patronage of Alexander Cumming’

by Charlotte Rostek (pages 38-47)

Summary: The Scottish clock and watchmaker Alexander Cumming (c. 1732–1814) owed much to his two major Scottish patrons, Archibald Campbell, Third Duke of Argyll (1682–1761) and Campbell’s nephew, John Stuart, the Third Earl of Bute (1713–1792). While the former is known to have fostered young Cumming throughout the first decade of his career in Scotland, the role of the latter in influencing Cumming’s career in London is less well understood. This article examines the available evidence, assessing existing scholarship and Cumming’s own 1812 publication to reveal a relationship which at times attains the status of partnership working to advance science through technology.

‘The horological career of Alexander Cumming’

by Jonathan Betts (pages 48-70)

Summary: Alexander Cumming (c.1732–1814), a Scottish-born watchmaker and mechanician, epitomises the eighteenth-century Enlightenment phenomenon of the ‘local boy made good’, attracting encouragement from aristocratic supporters and ultimately gaining acclaim and patronage from the King himself. Cumming had a particular interest in precision timekeeping and, in addition to new designs for precision watches and a longitude timekeeper, one of his most beautiful creations was a ground-breaking form of regulator which incorporated a barograph: a clock constantly recording the barometric pressure with a pen moving automatically on a paper chart. This article describes these exquisite examples of horological technology, reviews Cumming’s other interests in precision timekeeping, and summarises what we know of his life.

‘The ‘Kew trials’. Reflections of the highs and lows of English watchmaking’

by Mike Dryland (pages 71-87)

Summary: This article looks at the ‘Kew’ watch trials from 1884 to about 1925, as reported by the Horological Journal (HJ), and what the trials tell us about the watch industry in the period, and about the rise and fall of the trade in England. Back copies of the Horological Journal have been digitized and made available on-line to members of the Antiquarian Horological Society (AHS). Much of the material in this paper is based on analysis of contemporary reports in the HJ.

‘The changing face and place of John Bennett, 1846–1963 Part 2 – The twentieth century’

by David Rooney (pages 88-101)

‘Four watchpapers, excavating layers of history’

by Su Fullwood (pages 102-107)

Summary: Exploring how random finds and discoveries can help uncover the lives of those involved in horology at grass roots level. In this example, providing a timeline from a stratigraphy reminiscent of an archaeological excavation which uncovers the history and wider social implications of these often untold stories. (Read this article here)

‘Unfreezing Time #9’ by Patricia Fara (pages 108-109) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 42, Issue 4 December 2021

The front cover shows A rainy day in Cheapside, with the time ball at Sir John Bennett Ltd visible from afar, depicted in an 1891 publication. It is one of the many illustrations in the first part of David Rooney’s article on John Bennett, published in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘An early sixteenth-century drawing of a spring clock in a fifteenth-century astronomical manuscript’

by Philip A. Bell and Richard L. Kremer (pages 467-476)

Summary: Sketches opportunistically added to a fifteenth-century Vienna manuscript of astronomical texts have been identified as drawings of a spring-driven, drum-style clock or clock-watch of German origin. The principal drawing is annotated with technical information, including tooth and pinion counts, that suggest features characteristic of clocks made in the 1520s by Jakob Zech in Prague and others in Augsburg. We date the drawing to circa 1520; the clock on which it is based would therefore date from the end of the fifteenth or the early sixteenth century, earlier than any known and authentically dated clock of this type.

‘The changing face and place of John Bennett, 1846–1963 Part 1 – The nineteenth century’

by David Rooney (pages 477-492)

Summary: John Bennett (1814–1897) was a retail clockmaker, watchmaker and jeweller based in Cheapside, London, from 1846 onwards. He has been remembered for his views on the British horological industry and his use of modern advertising, marketing and publicity methods. Bennett retired in 1889 but the company he founded continued to trade in several London locations until 1963. This article explores the tangible public face of what became known as the ‘House of Bennett’, offering a case study in the history of horological retail that might prompt a wider examination of the subject.

'Harrison and Ellicott on watch wheel finishing, with notes on Samuel Hoole’

by Anton Howes and Anthony Turner (pages 493-510)

Summary: In this article we discuss two previously unpublished letters by John Harrison and John Ellicott, preserved in the archives of the Royal Society of Arts. The letters discuss the finishing of wheels for watches, and that by Ellicott identifies the watchmaker Samuel Hoole (1692–1758) as a pioneer of mechanisation in the late 1710s. We provide an account of this hitherto invisible inventor.

‘Carriage clocks that are five-minute repeaters’

by Thomas R. Wotruba (pages 511-518)

Summary: Since its earliest days at the outset of the nineteenth century, the carriage clock has provided features of distinct interest to horologists and collectors. Beyond their practical advantage of portability, many of these clocks offered attractive design and functional elements. One such functional element, originating before the widespread availability of electricity toward the latter 1800s, is the capability of indicating time at night when the clock dial was not visible. Known as repeaters, these clocks provided such measures on demand by means of a push of a button on the clock case. This article examines one such type, called a five-minute repeater, which has the capability of repeating on demand the measure of the last hour passed as well as the number of five-minute intervals passed since that hour.

‘Clocks at Ardingly College’

by James Nye (pages 519-524)

Summary: On 26 November 2012, the Dingwall Beloe lecture was given as usual at the British Museum, and in the convivial post-lecture atmosphere, created in part through Bonhams’ generous sponsorship of the refreshment, attendees swapped anecdotes and stories. One remarkable coincidence emerged, in that Peter Waller and I discovered we had something in common. We had both been custodians of our school’s clock system, at Ardingly College, in West Sussex, though our terms in charge were some twenty years apart. In March 2020, I led a party from the Electrical Horology Group on a visit to the school (reported in AH June 2020) and revisited familiar haunts from some forty-five years earlier. In the aftermath of the visit, while convalescing from Covid-19, I started to research the history of the clock system, and this short article is the result. (Read this article here)

‘Geo. Cotton & Sons – Clerkenwell spring manufacturers’

by Paul Myatt (pages 525-530)

Summary: Horological ephemera can lead to interesting discoveries. This article concerns two invoices from 1918 and a price list for spring makers George Cotton & Sons of Clerkenwell which reveal that they supplied tapered mainsprings for French clocks with cylinder escapements. Additional information shows that they were using Swedish spring steel for making mainsprings at an early date.

‘The firm of Drury Brothers, manufacturers of bells and gongs’

by Hugh Richards (pages 531-534)

Summary: Clocks that chimed on bells had long been popular but at the beginning of the nineteenth century, coiled steel gongs were first used in Continental Europe. By the middle of the nineteenth century, gongs were more widely available as an alternative, or an addition, to the use of bells in clocks. They became hugely popular and remained so into the twentieth century. A number of English clocks and French carriage clocks (the market for which was largely in Great Britain) used gong stands and bells that were branded JD or FD, usually appearing in an ellipse. Little or no research would seem to have been undertaken into the firm that might have made these bells and gongs, and this short paper is intended as a first step to rectify this.

Note: ‘The passive resistance watch’ by Chris McKay (pages 535-537)

‘Unfreezing Time #8’ by Patricia Fara (pages 538-540) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 42, Issue 3 September 2021

The front cover shows Béthune’s double lever pendulum escapement, in a clock dated c. 1725/30. This particular escapement is the subject of the article by Daniel Cousin in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘Salomon Coster, the clockmaker of Christiaan Huygens. The production and development of the first pendulum clocks in the period 1657 – September 1658’

by Ben Hordijk and Rob Memel (pages 323-344 )

Summary: Ever since in 1888 the first volume of Oeuvres Complètes was published, much has been written about Christiaan Huygens’s invention on Christmas Day 25 December 1656 of the application of a pendulum to a clock movement and the further developments of the early pendulum clock. By copying information, taking assumptions for granted as true evidence and through misinterpretation, the story of the pendulum clock threatens to get out of proportion. To put the history and the involvement of the protagonists back into perspective, renewed independent research was needed, based on original documents in the archives and libraries. This article covers the most important developments up to and including Huygens’s publication of Horologium on 6 September 1658.

‘Watch-glasses in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries’

by Anthony Turner (pages 345-348)

Summary: Two short texts from non-horological sources offer insights into how watch-glasses were produced in Early Modern Europe. They are here transcribed and translated with contextual commentary.

‘The ‘Chevalier de Béthune’ escapement’

by Daniel Cousin, translated by Anthony Turner, revised by Jonathan Betts and Anthony Turner (pages 349-364)

Summary: This article discusses Béthune’s double lever pendulum escapement. Both pallet arms of this recoil escapement have separate pivots with a frictional link between them. Movements with this escapement are rare and are found mainly in French clocks. Chevalier de Béthune, credited with this escapement in Thiout’s Traité de l’Horlogerie Méchanique et Pratique (Paris 1741), is most likely to have been Marie-Henri de Béthune (c. 1680–1744), who made his career in the Navy and was named a Chevalier of the Order of St Louis in 1728. As is explained, the escapement, although apparently novel, was not entirely without precedents. The article describes and illustrates several Normandy clocks with Béthune’s escapement, as well as one made in Guernsey which implies French influence.

‘Joseph Dodds and Robert Leslie – a mystery solved and an interesting discovery made’

by Jonathan Betts and Dale Sardeson (pages 365-377)

Summary: The Harris Collection at Belmont contains an unusual, ebonised balloon clock with moon-phase indication on top signed on the movement Joseph Dodds London, but ‘L. Dodds, London, BY THE KINGS PATENT’ on the white-painted dial. As no patents are recorded in the name of Dodds (either J or L), the clock’s signatures remained a mystery until a two-part article by Rich Newman in the NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin provided the solution. Dodds went into an unofficial partnership with American watchmaker Robert Leslie who shared his patents with Dodds. There the story would have ended, but for the discovery of a watch movement signed by Dodds in the collection of the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum in Bournemouth, prompting a closer look at the Dodds and Leslie business, a few of its known products and the watch patents themselves. (Read this article here)

‘Unravelling the history of George Savage’

by Andrew Blagg (pages 378-383)

Summary: George Savage had an impressive horological reputation in Victorian times. Now, credits attributed to him have become confused by conflicting dates which have drawn this reputation into question. The intention of this article is to settle this confusion as far as possible and allow future detailed examination of these credits.

‘Introduction of the Indian Standard Time. A historical survey’,

by Debasish Das (pages 384-395)

Summary: In ancient India time was measured in units called ghaṭīs by means of the sinking-bowl type of water clock. In the late fourteenth century, Firoze Shah Tugluq adopted this water clock and the time units, as did Mughal rulers from Babur onwards. This custom was also emulated by the East India Company at its factories in the seventeenth century. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the British Crown assumed direct control of the subcontinent, and began to replace the water clocks progressively by mechanical clocks. However, every locality followed its local time. In 1905 this plethora of local times was abandoned in favour of standard time 5½ hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). The present paper traces the change from the traditional Indian ghaṭīs to the European hours and later from local times to the Indian Standard Time on the basis of hitherto largely unpublished original documents.

‘The itinerant pawnbroker’ by Chris McKay (pages396-397)

‘Unfreezing Time #7’ by Patricia Fara (pages398-399) (Read the whole series of articles here)

‘The export of clocks and watches to China by East India Company captains in the early nineteenth century’

by Simon C. Davidson (pages 400-402)

Summary: This paper gives examples of the substantial investments made by East India Company captains in clocks and watches as part of their allowed private trade to sell to Canton Hong merchants catering to a market need for horological items then not produced in China.

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters to the Editor and Further Reading.

Volume 42, Issue 2 June 2021

The front cover shows one of a number of watches formerly owned by the Jewish horologist Alexander Grosz (1869–1940). They were unlawfully acquired for the Vienna Clock Museum in 1938, but have now been returned to the rightful heirs. The full story is told in this issue by Gerhard Milchram and Tabea Rude..

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

‘Helping to save the works of our old masters from oblivion’. The master clockmaker Alexander Grosz

by Gerhard Milchram and Tabea Rude (pages 172-186)

Summary: As part of the systematic research programme into the provenance of its collection, the Vienna Museum Group has identified seventy clocks and watches documented in the inventory of the Vienna Clock Museum, which had been unlawfully acquired in 1938. These clocks and watches were formerly owned by the Jewish horologist Alexander Grosz (1869–1940). During the Second World War, most museum objects were removed from the centre of Vienna for safekeeping from Allied air raids. The clocks and watches of the Vienna Clock Museum were hidden by the City administration and the Museum mainly in the vicarage at Klein-Engersdorf near Vienna, and at Thalheim Castle in Lower Austria. Both places were looted at the end of the war. Of the original seventy pieces that once belonged to Grosz, only forty could be found after the war. The Vienna Museum Group’s restitution programme, initiated by the Viennese administration and which started in 1998, finally traced the rightful heirs of Alexander Grosz, after long and difficult research. Following a recommendation from the Vienna Restitution Commission, the remaining clocks and watches were returned to them in 2017. This article aims to introduce Alexander Grosz as a clock and watchmaker, his ties and contributions to the international world of horology, and the known remnants of his collection. (Read this article here)

'What’s in a name? The family and early years of Thomas Tompion'

by Adrian A. Finch, Valerie J. Finch and Anthony W. Finch (pages 187-198)

Summary: Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) is one of the most important characters in English horology, described as ‘The Grandfather of English Clockmaking’. This article provides insights into his genealogy and early life. The Tompion family had rural Bedfordshire origins going back three generations and the clockmaker and his family are found in early Bedfordshire documents under the surname ‘Tomkin’. We provide a more detailed description of his family upbringing and show the clockmaker’s family are described by both surnames interchangeably. Thomas Tompion the clockmaker was also called Thomas Tomkin in his early years in London.

'1716: ‘A watch of new construction’ – a meeting of two great horological minds'

by Robert St-Louis (pages 199-218)

Summary: In 1715, the English watch/clockmaker Henry Sully was introduced to the French horloger Julien Le Roy in Paris. They became friends and collaborated on the development of a watch incorporating new design elements, which was then presented with success to the Académie royale des sciences in 1716. This article introduces the two horologists, describes their work on the watch (based on their own written memories of the collaboration and its outcome) and offers an example of knowledge sharing among horologists in early eighteenth-century Europe.

'George Graham and John Theophilus Desaguliers: mixed mathematicians'

by Ann McBroom (pages 219-242)

Summary: George Graham (1673–1751) and John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683–1744) can be characterized as mixed mathematicians, to echo a term used during the eighteenth century to describe the applications of natural philosophy to areas such as mechanics, engineering and astronomy. They were contemporaries at the Royal Society for almost twenty-five years, and collaborated on a surprisingly diverse range of topics, including event timing, friction, mechanical advantage, assessing human strength, and geared planetary machines. Desaguliers’s published lectures provide a rare window on their spheres of collaboration, and are the focus of this article. It is not intended to provide a comprehensive account of either man’s life or work.

'Two silent-pull timepieces with unusual features'

by Dennis Radage (pages 243-255)

Summary: This article describes two different approaches in configuring a timepiece with on-demand hour and quarter striking, both are signed Charles Gretton and date to circa 1700/05.

‘Unfreezing Time #6’ by Patricia Fara (pages 256-257) (Read the whole series of articles here)

'John Venning' by Chris McKay (pages 258-259)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters to the Editor and Further Reading.

Recent issues of Antiquarian Horology

Volume 42, Issue 1 March 2021

The front cover shows a detail of the dial of Joseph MacDowall’s regulator at the Yorkshire Museum, one of the clocks discussed in this issue by Angus Bell and Kenneth Cobb.

Photo © Kenneth Cobb courtesy of York Museums Trust.

This issue contains the following articles and notes:

'Charles and Joseph MacDowall and their helical clockwork'

by Angus Bell and Kenneth Cobb (pages 21-41)

Summary: This article describes the lives and works of Charles (1790–1872) and Joseph (1805?–1865) MacDowall. After working together in partnership at Leeds they moved to London where, independently, they continued to produce highly unusual helical-geared clockwork. Clocks described include the month-going skeletons for which the MacDowalls are best known and a unique longcase regulator. Helical gearing in clockwork by other makers is reviewed. A detailed examination of the MacDowalls’ helix lever is described in a Technical Note

'Technical Note: An examination of the MacDowalls’ helix lever gearing'

by Angus Bell and Kenneth Cobb (pages 42-49)

Summary: As described in the main text, the MacDowalls used a form of helical gearing — the helix lever — which they claimed had several advantages over spur gearing when used in clockwork. This Technical Note describes the differences between spur and helical gearing and examines in detail the specific form of the helix lever system. Evidence from this examination forms a basis for suggesting the manufacturing methods that the MacDowalls might have employed. Finally, the claimed attributes of the helix lever are discussed. The foundation of the Technical Note was an investigation by the second author for an MA thesis at West Dean College.

'Horological tradesmen and a Victorian directory scam – the Londoniad'

by D. J. Bryden (pages 50-60)

Summary: Almost annually from 1856 for some thirty years, J. T. S. Lidstone wrote and published the Londoniad. It purported to be a directory informing readers of the products of carefully selected leading London businesses. In essence Lidstone charged the clients whom he praised in verse. His claims of influence and a wide circulation in Canada were quite bogus. His verse was execrable. Some twenty horological practitioners were caught-up in a web of deceit that was exposed in the courts and ended in bankruptcy.

'French carriage clocks and late nineteenth-century decorative arts: Artistry in an era of art reform'

by Larry L. Fabian (pages 61-82)

Summary: The artists who decorated the dials and panels of fine Parisian carriage clocks during the second half of the nineteenth century experimented with a panoply of Aesthetic ideas and design vocabularies drawn from Rococo, Revivalist, Neoclassical, Romantic, and Japanese-influenced themes. The breadth of their artistic sensibilities is observable in illustrations found in standard carriage clock literature and in less accessible but publicly available exhibition monographs, international auction catalogues, and dealers’ inventories and archives. Their inventive and varied artistry interpreted visual styles that had become newly fashionable in Victorian fine art and in the decorative arts generally, and their collaboration with Parisian ateliers made these clocks more marketable in their time and more appreciated in ours.

'John Kaye of Liverpool – Can his clock predict the time and height of high water at Liverpool? '

by Steve and Darlah Thomas (pages 83-96)

Summary: Much has been written about rolling moon tidal dials which show the time of high water at a particular location. The clock by John Kaye, which provides the focus for this article, has a universal tidal ring attached to its moon dial, but also shows the time, and uniquely the height of high water, using three other parts of its dial, namely: data engraved on a fixed arch (above the moon dial), data engraved on a subsidiary dial showing the effects of the moon’s elliptical orbit, and data engraved on a second subsidiary dial showing the effects of wind speed and direction. Our purpose was to understand and use this extra data and to establish its accuracy (particularly the heights of high water) both when it was made c.1775 and today. In addition, the clock took us on a round-the-world voyage, led by the locations on its chapter ring; the accuracy of the placement of these and the reasons for their selection was also studied. (Read this article here)

'A process superior to any previously known. The introduction of electro-gilding for watches in mid nineteenth-century England'

by Michael Edidin (pages 97-102)

Summary: Traditional fire gilding of brass produced a beautiful appearance at the cost of human suffering from mercury poisoning. The development of electrochemistry in the 1830s and 1840s led to the displacement of fire gilding. Electro-gilding was more economical than fire gilding as well as safer for workers. A pamphlet of 1844 makes it clear that by this time electro-gilding was heavily used, but does not specifically mention its use for watch gilding. I have investigated the change from fire gilding to electro-gilding in a time series of watch movements by one maker, M.I. Tobias and Co. of Liverpool. There are sufficient data on M.I. Tobias watches to allow association of serial numbers with dates. Trends in gilding quality and composition make it clear that there was a sharp transition in gilding methods about 1845. This transition likely reflects trade practice generally.

'Harrison and Grimthorpe – the missing link'

by Geoff Sykes (pages 103-107)

Summary: This article discusses a flatbed turret clock in the parish church of Great Langdale in the English Lake District, installed in 1858 by James Harrison of Hull. A recently discovered letter provides proof that the clock was closely based on the design of a clock by E. B. Denison, Lord Grimthorpe.

‘Unfreezing Time #5’ by Patricia Fara (pages 108-109) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters to the Editor and Further Reading.