Vale of Glamorgan Tour, March 2023

On Friday morning 24th March, 32 members of the Turret Clock Group gathered at the Miskin Manor Hotel near Llantrisant in South Wales for their first event of 2023. It’s an area with few claims to fame apart from being the home of the Royal Mint since the early 1970s and, a century earlier, that of Dr. William Price, a Chartist, druid, and the pioneer of cremation! The region isn’t particularly noted for its turret clock heritage but a little research by members in the area located eight installations with movements from a range of styles and eras. A new departure – quite literally – for a tour in the UK was the provision of coach transport to and from all the sites. This had been requested by several regular tour attendees and proved popular, not only easing issues of timing and parking, but also generating an on-board camaraderie missing when everyone is in their own car.

The first morning saw a prompt departure from the hotel to see our first clock, which was only a couple of miles away on the opposite side of the M4.

Hensol Castle

Hensol Castle now forms part of the Vale Resort, which is a popular hotel, spa, and golf club, also being the tour base of the Welsh rugby squad. Although an historic site, the existing castle was largely rebuilt in the mid-19th century by owner Rowland Fothergill who introduced the courtyard and gatehouse containing a clock by B.L. Vulliamy. Prior to this it had belonged to Benjamin Hall MP. His son (also Benjamin, and an MP) was, of course, Commissioner of Works responsible for ‘Big Ben’. Throughout most of the 20th century the site housed a psychiatric hospital, and the current owners have invested a huge sum since the mid-2000s not only in developing the new hotel, but also gradually restoring the structure and interior of the castle to its former glory.

After taking the opportunity for a group photograph below the clock dial, we moved to one of the restored rooms in the castle where refreshments were served, and we were given a detailed talk on the history and restoration of the building by site manager Gareth Skeet who is justifiably proud of the clock in his charge. Arrangements for this visit had been made by Les Kirk who has thoroughly restored the movement, including converting it back to hand winding, and continues to maintain it in immaculate condition.

Although the clock room is large, the winding platform is less spacious, so our party divided into groups to climb to the upper part of the gatehouse, making full use of the brand-new handrails installed especially for our visit! The movement is typical of Vulliamy’s plate-and-spacer style, with deadbeat escapement, countwheel striking and bearing the number 1700. Drive to the single, slate dial is horizontal, and the long pendulum is equipped with a floor-mounted beat plate. We are indebted to Les Kirk not only for arranging for us to visit the clock at this very welcoming venue, but also for travelling down to show it to us in person, though sadly other commitments meant that he was unable to join us for the rest of the day.

Laleston

Roadworks caused quite a delay on what should have been the quickest route to our next visit in the village of Laleston which lies on the south-western edge of Bridgend. St. David’s church was founded in 1173 as a chapel belonging to Tewkesbury Abbey. It is an interesting building, not only for its sturdy tower, the battlements of which would look more at home on any of the nearby castles, but also because the building has no windows whatsoever on its north side. The friendly verger was on hand to welcome the group to see the late-Victorian Smith of Derby flatbed housed in the tower. Driving a single dial facing the main road through the village, this three-train clock has a pinwheel escapement, and ting-tang quarters.

Llantwit Major

Heading closer to the Vale coast, our next stop was in the attractive town of Llantwit Major which offered a range of lunch options before members made their way to the Town Hall, a building dating from around 1490 constructed under the lordship of Jasper Tudor. Over the centuries the ground floor has variously housed a school, a prison, and a slaughterhouse - though nowadays it’s the home of the town council and a small museum, with a large multi-purpose hall above. Access to the upper portion is via twin external flights of steps above which there is a porch structure with the clock dial in its gable, the small bell turret being on the roof of the main building. Internal structural evidence suggests the dial was originally in the gable of the main hall and was moved lower when the steps were roofed over. The recently restored clock dates from the late 18th century and has a wrought-iron cage frame very typical of the earlier work of its eminent London maker Aynsworth Thwaites. The going train has a one-and-a-half second wooden pendulum - most likely a replacement - with cylindrical bob controlling a recoil escapement and has bolt-and-shutter maintaining power. Striking (not currently running as further work is required on the bell and hammer) is rack-controlled and, unusually for Thwaites, has the fly at the front of the clock. The original octagonal wooden dial, illustrated in several historic drawings on display in the museum, was replaced in 1887 with a dial commemorating Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. This carries the name of well-known Cardiff clock maker Wladyslaw Spiridion, but the style of the hands suggests that it was supplied by Gillett & Johnston with whom Spiridion is known to have done business. The pendulum is probably their work too.

Wenvoe Castle

From Llantwit Major our route back to the hotel conveniently passed through the easternmost village in the Vale of Glamorgan - Wenvoe. The name may be familiar to those with an interest in broadcasting, as Wales’ first VHF television transmitter opened there in 1952. The current 855ft mast on the downs above the village is the third on the site but is far enough away not to be an intrusion on the landscape. Wenvoe Castle was rebuilt as a large country house in 1776-77 by Robert Adam, being his only project in Wales. Most of the house was destroyed by fire in 1910, but the grounds and the remaining stables and outbuildings were transformed in 1936 into Wenvoe Castle Golf Club.

Overlooking the stable yard from above the entrance arch is a substantial turret with bell, and four cast iron dials. The movement in the attic below is a small pinwheel flatbed by Smith of Derby. The clock was derelict for many years, and the bell and hammer had been removed and sold. About a decade ago, club member Peter Morris (a gifted engineer and vintage car enthusiast) removed the clock to his workshop and fully overhauled it before reinstalling it with additional pulleys and weight to allow it to run for a week. When originally installed it required daily winding with very little weight drop due to the floor below being accommodation for the grooms and stable lads. Peter also obtained a replacement bell from the Keltek Trust, while a hammer was sourced by one of our members in Cardiff and was re-engineered to suit the small bell. Access to the clock movement was via wide stairways, and we are indebted to the ground staff at the golf club who swept out and cleaned the attic area in advance of our visit.

The evening proved frustrating for the committee, with the hotel obviously being desperately understaffed. In another break from tradition, we’d opted for a buffet meal with an opportunity for members to circulate more than at a formal dinner. Unfortunately, anyone present will attest to the fact that the catering was, at the very least, disappointing. The evening was saved by Chris McKay who gave an engaging talk about his work on the historic clock at Port Regis school, and his background research into its origins. This has been encapsulated in a book, and many of those present took the opportunity to pre-order their copies.

Bridgend

Saturday morning dawned with a 10am departure for Bridgend and the town’s main parish church, St. Illtyd’s, in the Newcastle area overlooking the town centre.

Not a great deal is known about this two-train clock, which hasn’t run for over twenty years. It has a forged iron frame with wheels of brass and has been modified to drive the single octagonal wooden dial on the south face of the tower. The current, long pendulum is likely to have been introduced at the same time. There was much lively discussion with a consensus among members that it dates from around the mid-18th century, but the definitive answer, along with those to other questions, may yet be found in church records.

St Brides Major

Next stop for the tour bus was to the south in St. Brides Major. The parish church of St. Bridget sits on high ground in the centre of the village, and the west tower houses a fine ring of six bells and a ting-tang quarter striking clock by Gillett & Johnston. Dating from 1913, by which time the Croydon firm had switched to plate-and-spacer construction, it has a very substantial ‘heavy-duty’ appearance, and employs a pinwheel escapement with seconds pendulum, so made an interesting comparison with the Smith of Derby clock we’d seen the previous day at Laleston.

Cardiff Castle

The penultimate visit on the tour actually took us out of the Vale of Glamorgan and into Cardiff city centre where, following a lunch break, the group assembled for a private tour of the Castle clock tower. Cardiff Castle has a long history beginning with a 3rd century Roman fort, the foundations of which were built upon by Robert Fitzhamon, the Norman Lord of Gloucester, in the 11th century. By the mid-18th century, the buildings had passed through the hands of a number of noble families, and a Georgian house had been built against the western wall and towers. In 1766 ownership passed by marriage to the Bute family, and by the time the 3rd Marquis inherited in the mid-19th century, the family coal fortune had reputedly made him the richest man in the world. He set about transforming the castle’s living accommodation in collaboration with the architect William Burgess, who had trained under Pugin. Burgess created lavish and opulent interiors in a faux-Gothic style, rich with murals, stained glass, marble, gilding and elaborate wood carvings. Each room has its own theme, including Italian, Arabian, and even a Mediterranean roof garden. Burgess’ first work on the site in 1869 was to start construction of a new clock tower at the south-west corner adjacent to the main bridge over the Taff which flows to the west. The theme chosen for the decoration in the tower, completed in 1875 was, unsurprisingly, time. There are ‘below stairs’ rooms at basement and ground levels, but the first room accessible from the main 202-step spiral staircase is the Winter Smoking Room – a post-dinner haven for the men to enjoy port and cigars and including a carved stone devil above the doorway, to dissuade the ladies of the household from daring to cross the threshold! On the next floor is the Batchelor’s Bedroom. The castle management were fortunate to be able to arrange the return of the original Burgess-designed bed which had been sold when the Bute family donated the castle to the city in 1947. The alabaster bath in the adjoining ‘en-suite’ was reputedly fashioned by Burgess’ craftsmen out of a re-purposed Roman sarcophagus.

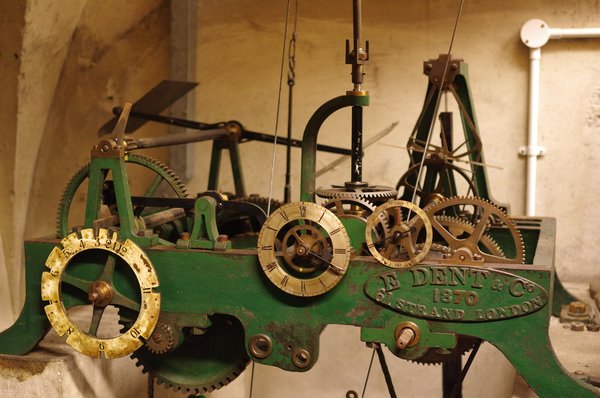

The main focus of our visit was the room above this. The clock room has another two thick doors inside the main entry from the stairs in a failed attempt to insulate the other rooms in the tower from the sound of the hour bell. The clock was ordered from Dent, no doubt their reputation for the Westminster clock informing the architect’s choice. It is dated 1870, although it wasn’t fixed in place until five years later. The flatbed movement has a gravity escapement and drives four six-foot skeleton dials, the hours being struck on a large bell from the Warner foundry. The whole installation is in one room, and there are gilded cast iron grilles below each dial to give sound egress. The clock was hand-wound by council staff until 1971 when Gillett & Johnston endless-chain autowinders were fitted. These have been superseded in the last decade by new, compact units by Smith of Derby. Of interest is a long vertical slot in the south wall of the room opposite the movement, which is the opening into the original weight shaft that was built within the thickness of the stone wall right down to basement level. The driving weights must have been long and narrow.

Above the clock room is a small kitchen and ‘privy’, but the visual climax comes at the top of the staircase in the magical Summer Smoking Room. The theme here is ‘The Universe’ and the decoration culminates in the high, painted ceiling where the stars and constellations appear above the sun, represented by the chandelier. When this was lit by candles their light would have reflected from inlaid glass in the ceiling to give the atmospheric illusion of the night sky. Visit the castle website at cardiffcastle.com for photographs of these and many more rooms in the building, along with a full history.

Barry

Boarding the coach for our final visit, we headed back into the Vale and the coastal resort of Barry. Now mostly associated with TV sitcom ‘Gavin & Stacey’, for many years the north-western perimeter of the No.1 dock was home to Dai Woodham’s scrapyard which was the intended final destination of the great number of ex-British Railways steam locomotives which went on to survive in preservation. On the highest point above the dock, and overlooking the beach at Whitmore Bay, stands the parish church of All Saints built in 1908 to serve the town’s rapidly increasing population. To the original nave a chancel and tower were added in 1915, and in 1946 the parish war memorial took the form of a turret clock and a chime of ten bells installed by Gillett & Johnston.

There is nothing remarkable about the clock movement - which is their standard motor-wound gravity timepiece of the time – and associated electric hour-striking unit. It drives an unusually styled illuminated dial high on the north side of the tower facing the local shopping thoroughfare.

However, what IS a rarity now, is the survival of one of Gillett’s electro-pneumatic chime systems. Interchangeable bronze drums are provided which close contacts that, through a relay board, energise electromagnets that allow compressed air into the cylinders of pneumatic rams. These pull down on wires which move the clappers in the stationary bells. The use of carillon-style internal clappers rather than clock hammers is interesting, and the 18cwt tenor bell actually has two clappers pulling in opposite directions. The one on the north was attached to the chiming mechanism, and that on the south to the hour strike. Sadly, although the system was partially operative until a few years ago, it no longer functions. It is complete though, and worthy of preservation if not restoration. As always, financial considerations mean that it’s not a current priority. We are grateful to the Rev’d Canon Zoe King and the church’s fabric committee for granting access for our visit to this rare survivor of a once technologically advanced system by one of the country’s leading turret clock manufacturers, which proved a fitting finale to our tour in an area previous unexplored by the Turret Clock Group.