Who was Master Humphrey?

This post was written by James Nye

Sometimes I'm asked about my lifelong obsession with clocks and what on earth I see in them – or perhaps what they say to me.

In reply, I'll comment about their longevity and the fact they tend to last longer than people. I'll observe that they tick out the lives of those around them – that they are observers in whom the events they witness become inextricably bound up.

And I'll say that sometimes, when we are researching or writing about those subjects, our clocks help us along with helpful nudges and hints.

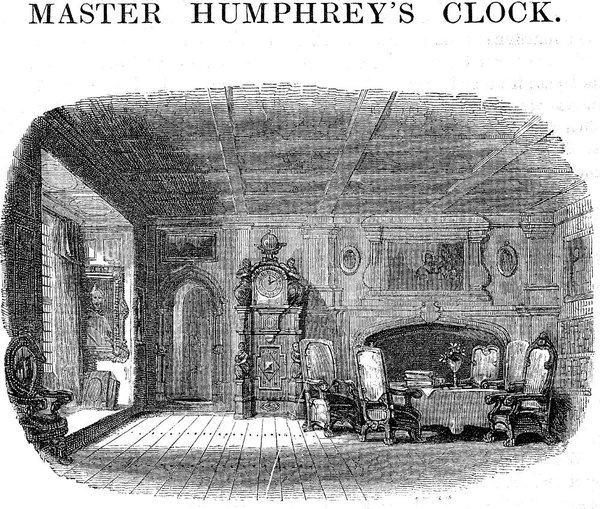

It pleases me to know that Charles Dickens had something of the same sense. In Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840), the eponymous timepiece is imbued with the same timeless and comforting qualities.

Discussing the work with a friend, Dickens describes a quaint old character who has a great affection for a clock:

"He has got accustomed to its voice, and come to consider it as the voice of a friend […] its striking in the night has seemed like an assurance to him that it was still a cheerful watcher at his chamber door […] its face seemed to have something of welcome in its dusty features, and to relax from its grimness when he looked at it from his chimney corner."

Not very practically, Dickens had the notion that the trunk of the clock could be a safe repository for the manuscripts of a club that would meet to read to each other. He says:

"I mean to tell how that he has kept his old manuscripts in the old, dark, deep, silent closet where the weights are, and taken them thence to read (mixing up his enjoyments with some notion of the clock), and how, when the club came to be formed, they, by reason of their punctuality, and his regard for this dumb servant, took their name from it."

The Horological Journal of October 1912 (available online to AHS members) carries a pleasing account of Dickens’s inspiration.

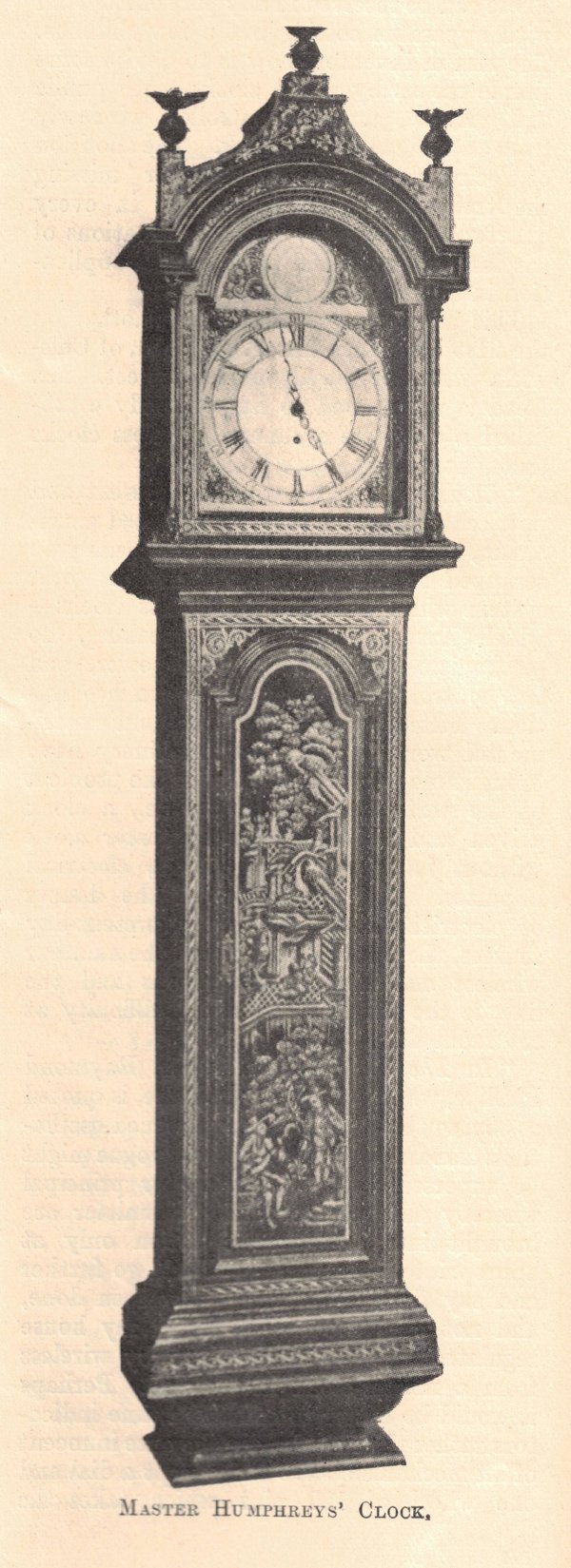

In 1837, Dickens spent several weeks in Barnard Castle, Yorkshire, researching school conditions for Nicholas Nickleby. While there, he encountered a clockmaker named William Humphreys.

In 1828, Humphreys had acquired an ornamental seventeenth-century Dutch longcase clock with a worn-out movement. The following year, having fitted it with a new mechanism, he installed it in a niche to the right-hand side of his shop door.

This was the real "Mr Humphreys' clock," consulted occasionally by Dickens on his local journeys. He came to know not just the clockmaker himself but his son, Master Humphreys. In Dickens's mind, "Humphreys" became "Humphrey," and thus was born the inspiration of his 1840 work.

And as I type, I am accompanied by a comforting tick from a shelf just beside me. If I wait a few more minutes, I will be reminded of the hour...