When is a wrist watch not a watch?

This post was written by David Read

In February 2013 it was leaked that Apple was experimenting with an iWatch. However, six months later and at the time of writing this blog there is still no news from Apple and the technical press is now guessing that the project has hit battery problems.

If only Dick Tracy, the famous cartoon sleuth, was still around to find out what the bad guys are up to and get at the iWatch facts. Tracy had sported a remarkable watch on his wrist since 1946 and now, 67 years later, Time Magazine described that watch as 'the most indestructible meme in tech journalism'.

For decades now, it has been nearly impossible to write about communications technology combined with a wristwatch without invoking the plainclothes cop with a special watch on his wrist who first appeared in 1931, even though the days when one could follow Dick Tracy’s adventures in a daily newspaper have long gone.

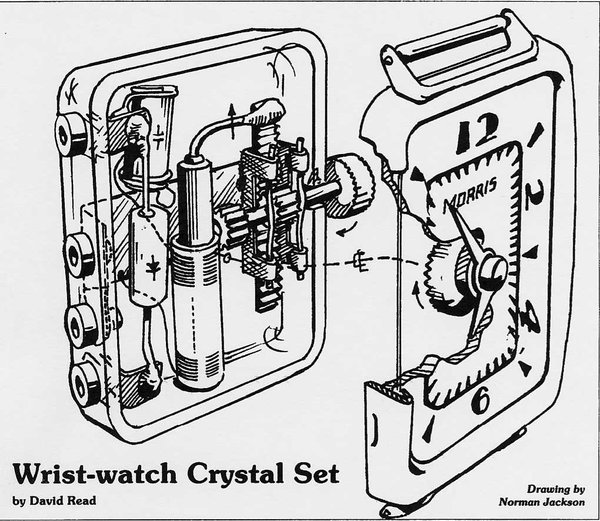

Popular science fiction is always years ahead of the technologies that turn dreams into reality. However developments in solid state electronics had, by the 1940s, enabled the large galena and cat’s whisker detector of the crystal set to be produced as a tiny point-contact diode and placed inside a wrist watch case as in the Morris watch shown here.

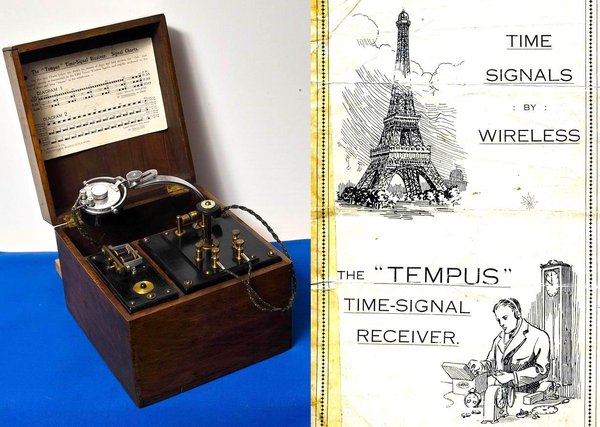

But is this a watch? No, it’s a crystal radio. However, horology and radio have a long shared history involving frequency and time. This clandestine wristwatch radio can receive time signals in exactly the same way as mariners and watchmakers did from 1912 in order to check their chronometers, clocks and watches against the timecode transmitted from the Eiffel Tower. My image of the Tempus crystal radio and instructions sets the scene.

The illustration of the Morris watch shows a standard-sized watch case made of chrome-plated steel. The dial, signed Morris, is in typical 1940s style. The standard of manufacture is high and the disguise on the wrist is perfect. The case back is made of moulded Perspex to provide an insulated chassis on which the circuit can be built without special measures to insulate the components, aerial, earphone sockets and associated wiring.

The winding button is actually a dial knob and connects to a rack-and-pinion control of tuning in which an iron-dust core is moved within the aerial coil and tunes the required frequency by altering the coil’s inductance. This assembly is connected to the earthy end of the coil and also to the metal case thus providing a body earth to stabilize the circuit whilst tuning. A tiny sealed point-contact crystal detector is enclosed in an evacuated glass tube and a capacitor across the coil completes the circuit.

A second pinion on the winding stem connects with a crown wheel on which the hands are mounted. This alters the position of the hands on the face of the watch and provides a scale against which a station can be memorized or noted. Using the wrist watch crystal set in conjunction with a deaf aid as an amplifier would have allowed the use of a short aerial such a bedstead and completed the disguised operation.

The drawing was made for me in the 1980s by my late dear friend Norman Jackson, an outstanding engineer and artist whose illustrations always showed at a glance how things work; something that photographs can never match.

It is interesting to speculate why such a radio was made and I have never seen another. However, the Morris watch cannot be unique because it is a professionally designed object requiring bespoke production tooling and Perspex moulding facilities. The public market for such clandestine receivers would have been tiny and with no chance of recovering the costs involved. Without a consumer market for this item it would seem possible that it was funded by a government agency and the headline news today shows that such agencies are still active in the ancient arts of listening, spying, and gathering information.

And another thing – yes it does work!