Whatever makes you tick!

This post was written by James Nye

I’m fascinated by machines that are largely clockwork, but which don’t show the time. A visit by West Dean students to The Clockworks meant digging some intriguing items out of the stores.

Consider the early electricity meter. Early on Jules Cauderay used an electrically maintained balance wheel as a timebase, and then occasionally engaged the dial work (recording units) depending on the load.

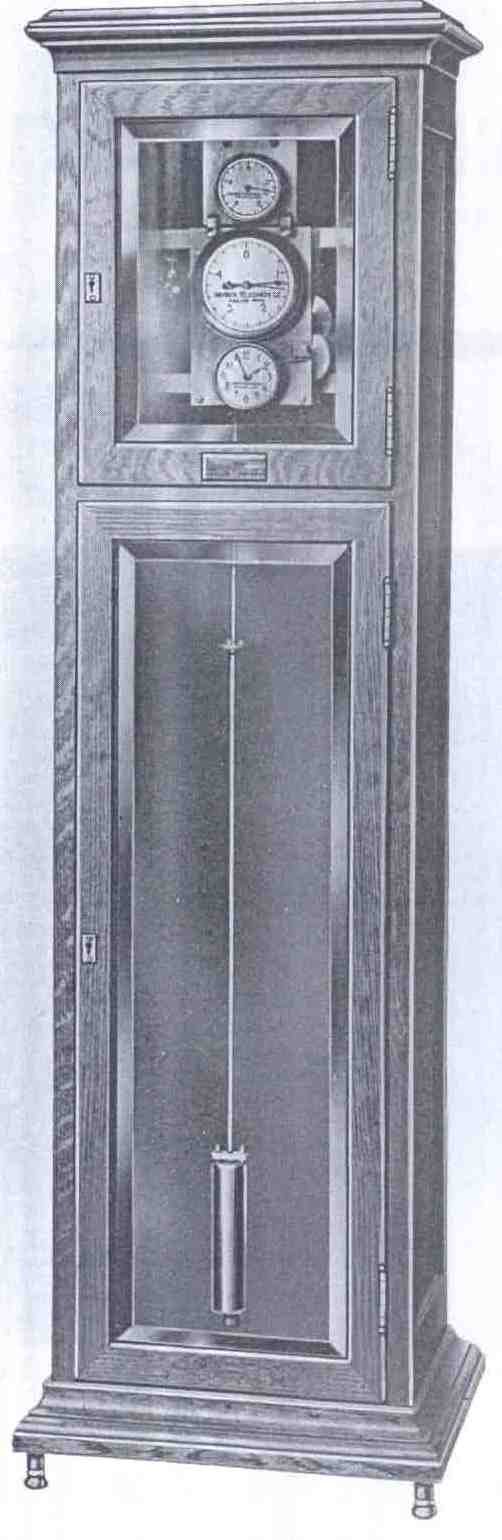

It took Herman Aron to come up with an accurate meter, using two pendulums, one for timing, the other influenced by the load to be measured. Integrating between the performance of the two trains allows the dials to show consumption.

‘Aha!’ you say, ‘How does the customer know the timebase is accurate?’ Simple – Aron arranged for the trains to swap roles regularly. A great place to see one working is Amberley Museum.

Henry Warren (synchronous motor man) used two trains to keep the power grid stable. When frequency stability was poor, he developed a device with a synchronous clock showing ‘grid time’ and a pendulum clock showing true time. By regulating turbine speed, accurate synchronous clocks for the home were possible.

Our UK ‘grid code’ specifies close tolerances over 24 hours, so your clock can be many seconds wrong, but on average, correct! At an AHS synchronous day, Michael Maltin fixed up a chart all round the room (like the Bayeux Tapestry!) showing a week’s (volatile) grid time versus GMT. You can see what the grid is doing right now here.

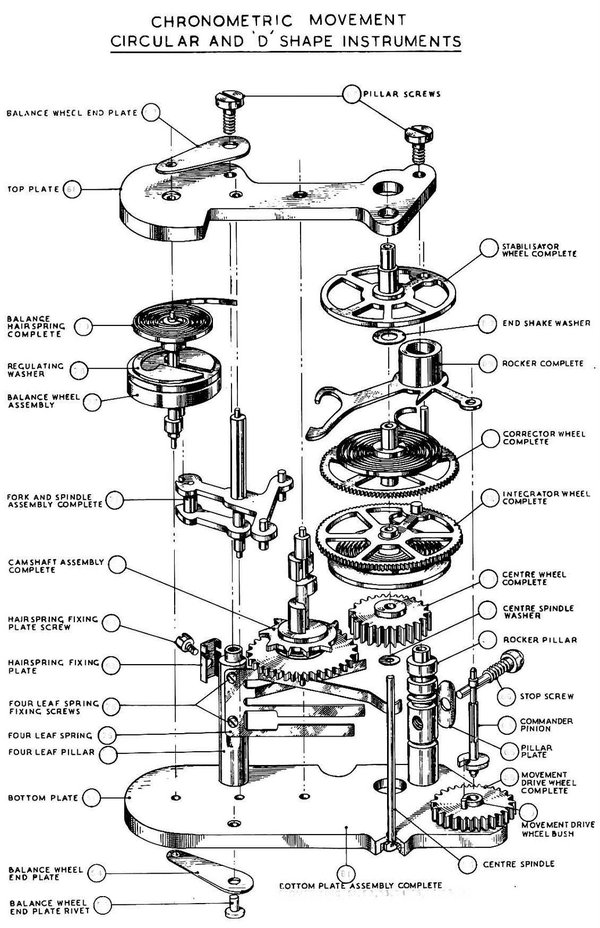

Another device that integrates two trains is the ‘chronometric’ speedometer, developed by Jaeger. This uses a balance wheel escapement, powered from a drive shaft as a timebase, allowing revolutions to be counted. A complex series of gears move the integrator and recording wheels back and forth, and the needle shows the last recorded speed. At least one manufacturer had to deal with customers who didn’t like the speedometer continuing to tick after they had come to a halt!

Lots of ticking – not much time!