Unfriending in the eighteenth century

This post was written by James Nye

Recently, AHS member Jeremy Evans, a highly distinguished former horology curator at the British Museum, donated a remarkable archive of research papers to the Society. It was amassed over a long career and fills four metres of shelves at our Lovat Lane headquarters. It was most generous of Jeremy, and we were delighted to receive it!

While waiting for the papers to be catalogued by our Archivist, Dorota Pomorska, I decided to have a bit of a delve. In an index of horological articles that Jeremy had found in eighteenth-century newspapers, I noticed the entry ‘Matrimonial Strife’. Curious, I looked further.

Usually, during a male clockmaker’s life, his wife is invisible in the historical records. Sometimes, though, these women do make appearances. Elopement could be the cause. It is now customary to think of elopement as the young running away to marry without parental consent. Yet in the eighteenth century, married women also eloped – from their husbands. Sometimes this was with a lover. The word could also mean ‘escape’.

In a world of sexual inequality, women had few options. Maureen Waller, in her work The English Marriage: Tales of Love, Money and Adultery (John Murray, 2009), wrote, ‘On her wedding day, a woman stepped into the same legal category as wards, lunatics, idiots and outlaws’.

One reason why women left their husbands was domestic violence. Abuse of a spouse is well-exemplified in the cruel treatment meted out to Dorothy Arnold by her husband John, of chronometer making fame and usually a horological hero, detailed in Martyn Perrin’s article ‘The secrets of John Arnold, watch and chronometer maker’ (Antiquarian Horology, June 2015).

In other cases, we do not know the underlying reason why women left their husbands and can only speculate.

In Jeremy’s archives was the following list of horological escapees:

- Sarah the wife of William Gibbs of Upper Moorfields, clockmaker (Daily Advertiser 27 June 1741).

- Mary the wife of Edmund Pottecary, clockmaker, of […] St. Andrew Holborn (Daily Advertiser 6 August 1745).

- Sarah, the wife of Thomas Linter, watchmaker of Cripplegate (Daily Advertiser 6 August 1746).

- Elizabeth, the wife of John Simmons, watch-case maker in St Bartholomew’s the Great (Daily Advertiser 11 September 1746).

- Thamisian Symonds, wife of John Symonds, watch-case-maker in St Martin Ludgate (Daily Advertiser 20 May 1747).

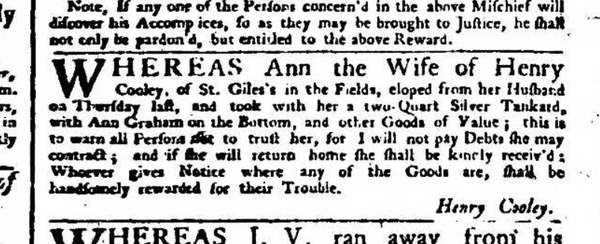

- Ann, the wife of Henry Cooley, clockmaker of St Giles’s in the Fields (Daily Advertiser 11 May 1748).

- Rachel, wife of James Webb, clockmaker in Bristol, who ‘lives an irregular life’ (London Gazette 21 February 1761).

- Mary, wife of John Lowder, clockmaker and mariner of St Botolph’s, Aldgate (General Advertiser 7 October 1749).

Each announcement followed a more-or-less standard form of words — essentially, ‘This is to warn all persons not to credit, trust, or lend any money to...’ and further ‘I will not pay any debts she may contract’.

It’s obvious why husbands chose to make their news so uncomfortably public. At heart, it was damage limitation, though Mr Azier, watchmaker, seems to have been unlucky. He was pursued for a debt of £150 run up by his estranged wife for ‘Velvet, Damask Cloaths, Diamond Rings, Gold Watch etc’. On that occasion, the court ruled that ‘none in this case could justify the giving of credit to another man’s wife, for more than necessaries for food and apparel, but not for superfluities like those.’ (Caledonian Mercury 5 July 1725). For whatever reason, whether justified or not, Mrs Azier seems to have sought a way to punish her husband.

The AHS Women and Horology project is advancing our knowledge of the roles that women have played in the story of time. Do contribute if you can!