Time and efficiency

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

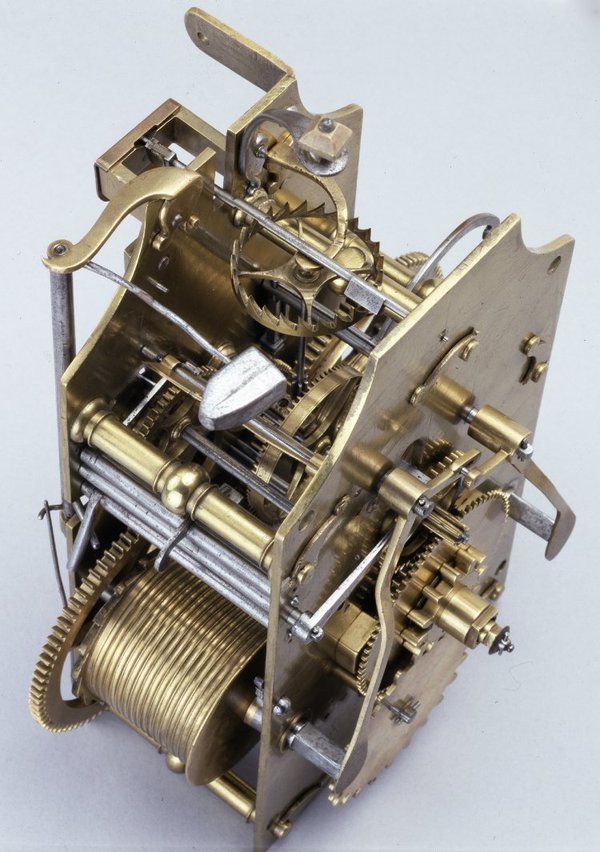

Last time I looked at how clocks and watches obtain and store their energy, but I thought it worth mentioning how carefully they use it.

Some clocks are designed to have a surfeit of energy – for instance turret clocks must be able to overcome ice and snow loading. But, in general, efficiency is paramount in horology.

A 17th century eight day longcase clock typically runs on a 12lb weight (5.44kg in new money) which drops about 5 feet in the eight days. Based on those numbers, my dimly recollected school physics tells me that such a longcase clock must use about 1/8500th of a Watt of power.

Let us compare that with something familiar. The best example I can think-up is the motor that vibrates a mobile phone – these run at about 0.16W – i.e. that little motor that tickles in your pocket could run about 1500 longcase clocks. Or, looking at it another way, the energy used to boil an egg would keep a longcase clock going for 80 years. Not bad for a 300 year old machine.

The Atmos clock (which I mentioned before for its ability to be powered by changes in air temperature) is in another league – the little mobile phone motor could run 700,000 of them. 1 boiled egg, 38000 years.

How are they so much more efficient than the longcase clock? Apart from being closer in scale to watch work, the Atmos clock benefits from 250 years of horological development. They are factory made, not hand made – this facilitates much closer tolerances and optimal gear tooth shapes. Like fine watches, their bearings are jewelled (jewels are little rubies with holes drilled in them – very smooth and very hard wearing). They also have a steel torsion pendulum which is excellent at conserving energy.

Something else to bear in mind is that we expect our clocks and watches to run non-stop for years on end, between services, without breaking down. Do you ask the same of your car? Remember that when your clock repairer presents their next bill to you!