The compound pendulum in a precision timekeeper?!

This post was written by Tabea Rude

Popular and well known examples of compound pendulums in horology are found in French novelty clocks. They can be camouflaged as an innocent sailor, as in the mantel clock on display at the Royal Observatory Greenwich...

...but mostly compound pendulums are regarded as a nightmare when it comes to precision.

This was not always the case, as I found out in the conservation and research into an electromechanical double pendulum clock, patented by M. Pierre Sellier in 1909.

Sellier’s patent clock (on display at The Clockworks) uses a compound pendulum to provide the drive to the hands, while a ‘free’ pendulum controls the electro-magnetic impulsing of the compound pendulum, by making and breaking the drive circuit.

Sellier’s invention was, like most other compound pendulums, lacking in precision, but in the early 20th century he was not alone in using a compound pendulum in the quest for precision time keeping.

In other horological circles, consideration was given to the compound pendulum as a potentially useful component.

While in 1909 the Deutsche Uhrmacherzeitung described the compound pendulum as a ‘rape of the pendulum principle’, a major article by Prof. Dr. Ing. H. Bock in 1929 in the same magazine reported on a compound pendulum as a precision break-through.

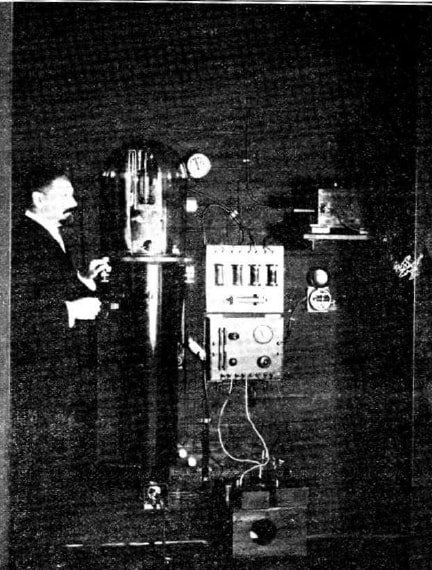

After criticising the suspension spring type used in Shortt’s free pendulum for its variable elasticity modulus, Bock introduced Dr. Max Schuler’s idea of exchanging Shortt’s free pendulum for a compound pendulum resting on a knife edge.

He claimed that Schuler would soon be able to measure all the anomalies in the Earth’s rotation and outperform the Shortt clock with ‘German toughness’.

The Schuler clock has ended up at the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum at Furtwangen, and no doubt we will hear more about in due course!