Sundials can be sobering and noisy

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Whereas a clock or a watch tells us at a glance what time it is, finding the time with a sundial is less easy. And it only works when the sun shines. Serious limitations, one might argue.

But this does not make them less attractive or fascinating. Indeed, there are societies entirely devoted to the subject, such as the British Sundial Society (BSS) whose members study and record old sundials and enjoy designing and discussing new ones.

Sundials come in many sorts. Like clocks and watches, they range from pocket-sized (Figure 1) to monumental (Figure 2), and from straightforward to mind-bendingly complicated.

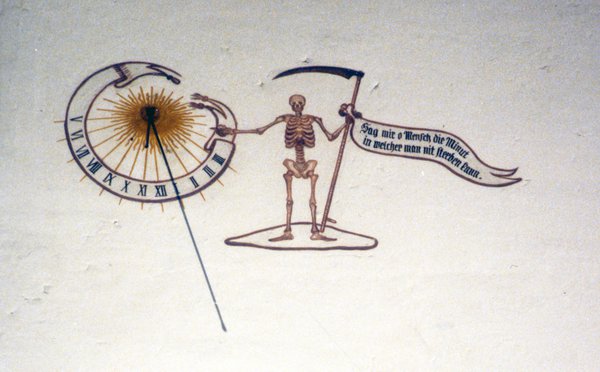

What I like about them is that they can come with arresting imagery and texts. An example is the sobering memento mori we saw years ago on an Austrian church (Fig 3). The Grim Reaper would fit perfectly in the exhibition Death: A Self-Portrait, currently at the Wellcome Gallery in London.

Sundials are quiet. Not for them the reassuring tick-tack of a clock, or the quarterly or hourly chimes.

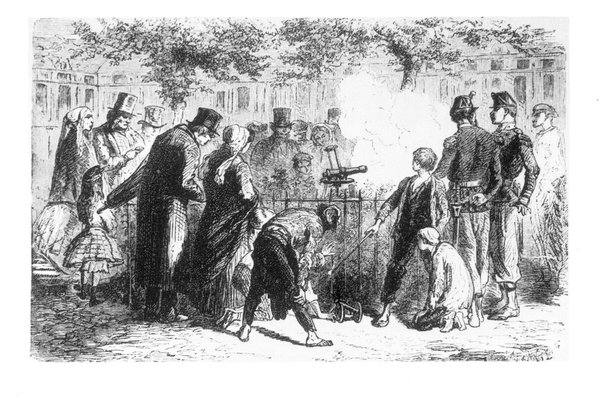

But there is one exception: the cannon dial, also known as solar cannon or noon cannon (Fig 4). It is fitted with a burning lens, so arranged that the Sun’s rays are directed to the touch hole of a small cannon. At noon precisely, it goes off with a bang! People could set their watches by it (Figs 5 and 6).

It was an acoustic variant of the Greenwich time ball, which for generations has been dropped every day at 1 pm sharp – initially for ships’ navigators to check their chronometers, and now purely as an enjoyable public spectacle.