Patenting precision: early motorsport timekeeping

This post was written by Marie Reber Ondrejikova

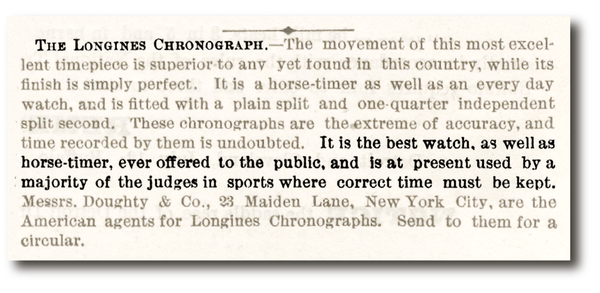

An advertisement dated 29th January 1881 in the New York weekly The Spirit of the Times proclaims that: ‘a gentleman not only secures a timer for the track, but also an excellent watch for ordinary purposes, that will last him a life-time. The timer beats fifths of seconds, which is admitted to be the most accurate movement’.

The watchmaking workshop founded by Auguste Agassiz produced its first movements under the Longines name in 1867, and in 1879 brought to market its first chronograph movement, the calibre 20H. Although this calibre did not include a minute totaliser, it established the Longines name on American racecourses.

In these early years the focus was on horse racing but by 1886, Longines was already equipping the majority of sports judges.

In 1889, Longines developed its second chronograph, the calibre 19CH, followed by increasingly sophisticated chronographs such as the calibre 19.73 in 1897, capable of measuring times to one-tenth of a second and intermediate times.

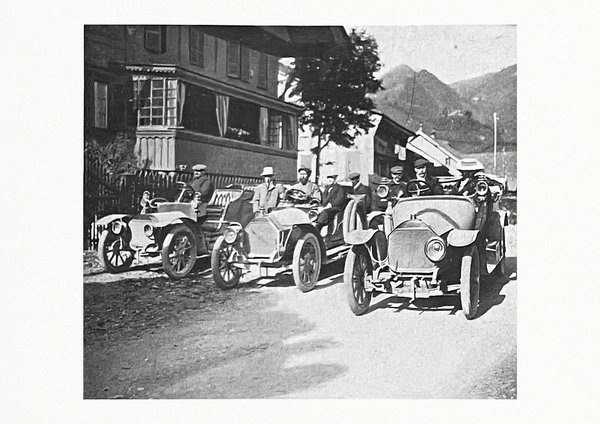

These technical advancements were well timed, with the first automobile race in the United States taking place in 1895.

The early motorsport races were spectacular events. The public were thrilled by the courage of the drivers and admired the beautiful machinery, still rarely seen on the roads. These competitions played an important role in the development of the automobile and in improving the performance and reliability of vehicles.

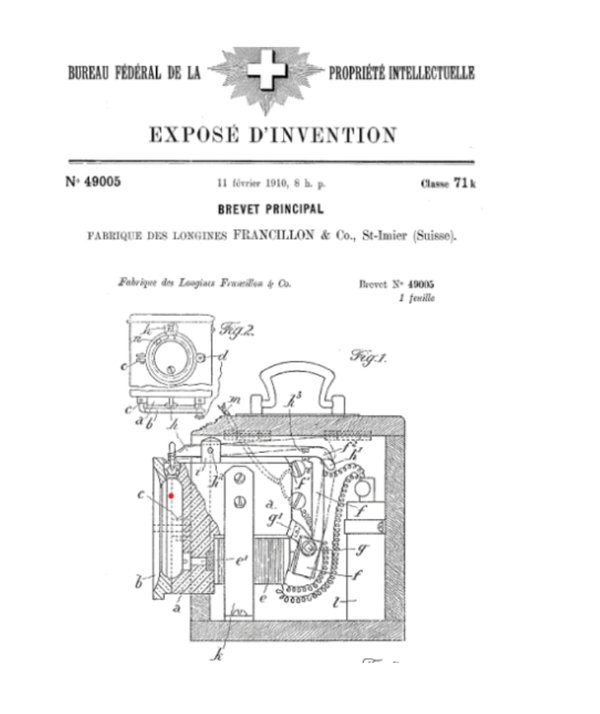

As motor cars gained popularity and speeds increased, new sporting events emerged alongside professional timekeeping. In 1910, Longines filed patent CH49005 for an electric control device for a pocket chronograph. This patent was of particular importance in the field of motor sports timekeeping, as it explicitly specified that the invention was intended for the velocipede and automobile disciplines.

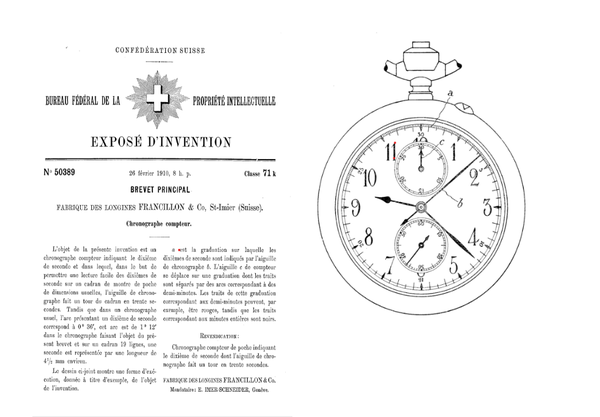

In addition to this patent, in 1910 Longines also filed a patent for a chronograph counter displaying time to the tenth of a second (patent no. 50389), an innovation that required a high-frequency movement with 36,000 vibrations per hour.

These early patents laid the foundations for the very first sports timekeeping service, adding cutting-edge electrical skills to watchmaking know-how, and the creation of timekeeping control systems.