Night watchmen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Richard Wagner set his glorious opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-singers of Nuremberg) in that German city in the sixteenth century.

In the second act a night watchman sings (the English translation in the vocal score is somewhat awkward as it aims to preserve both metre and rhyme):

'Hark to what I say, good people;

strikes ten from every steeple;

put out your fire and eke your light,

that none may take harm this night.

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat zehn geschlagen;

bewahrt das Feuer und auch das Licht,

dass Niemand Schad‘ geschicht.

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

The act concludes with his re-appearance:

'Hark to what I say, good people;

eleven strikes from each steeple;

defend you from spectre and sprite;

let no power ill your souls of fright!

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat elfe geschlagen;

bewahrt euch vor Gespenster und spuck,

dass kein böser Geist eu’r Seel‘ beruck‘!

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

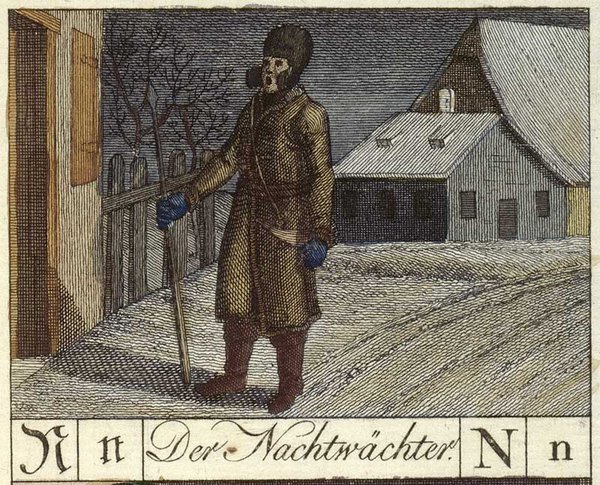

From the middle ages until late into the nineteenth century, the night watchman patrolling the streets at night, calling the time and keeping an eye out for any kind of mischief or irregularities, were a common figure in many towns and cities.

Although he set his opera in the sixteenth century, watchmen were probably still active in Nuremberg when Wagner wrote his opera in the 1860s.

One century earlier, an Englishman visiting Nuremberg recorded in his travel journal 'Every evening about nine o’clock a fellow goes up and down the streets singing, and gives notice of the time of night, and bids people put out their candles. About the same time and at three in the morning trumpets are sounded.' (Sir Philip Skippon, An Account of a Journey Made Thro’ Part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and France , 1752).

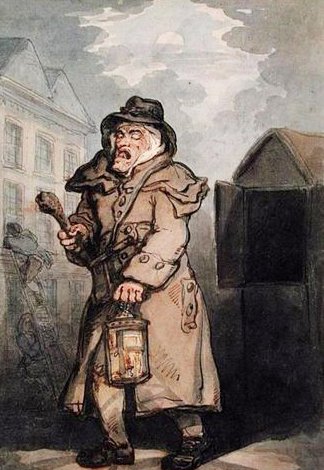

In her book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London , Judith Flanders writes that for a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock, stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time.

The patrols of the night watchmen were not an undivided pleasure.

In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Tobias Smollett has a long-suffering character say, 'I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants.'

Acknowledgment. It was Wagner’s opera that made me want to know more about these night watch men, and I found much information in this article: Philip McCouat, ‘Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night’, Journal of Art in Society (2014), www.artinsociety.com.