Japanese time

This post was written by David Thompson

From the first appearance of the clock in Japan, when the Spanish Jesuit priest, St Francis Xavier, arrived with gifts for the Emperor, including at least one clock, in 1551, the story of mechanical timekeeping in that country has been an intriguing one, and one which lasted until the end of the Edo dynasty in 1873.

From 1612, when the Europeans were expelled from Japan and the country was closed to outside influences, the Japanese clockmakers were on their own for over 250 years. What they produced in terms of clocks was indeed ingenious.

First of all, how was time measured in Japan in that period? Take the hours of darkness and divide those up into six equal parts. Then take the hours of daylight and also divide those up into six equal parts and there you have it. Clearly if the day is divided in this way, the length of the daylight periods and those of darkness will vary throughout the year except at the equinoxes when all the hours will be equal and equivalent to two hours of European time.

Unfortunately, mechanical clocks like to keep equal unchanging hours as best they can. So, what did the Japanese clockmakers do in circumstances where they had no access to what was going on in far distant Europe at the time?

Three quite effective methods were devised to get round the problem:

- to have two separate oscillators in the form of weighted swinging bars known as foliots with adjustable weights to change the rate of the clock.

- to have moveable markers either on a round dial or on a flat bar, depending on the type of clock.

- to have a series of plates, usually fourteen, which would be changed periodically depending on the time of year.

In all three types the time indication would have to be adjusted twice per month.

When it came to style, there were basically three types of clock in Japan:

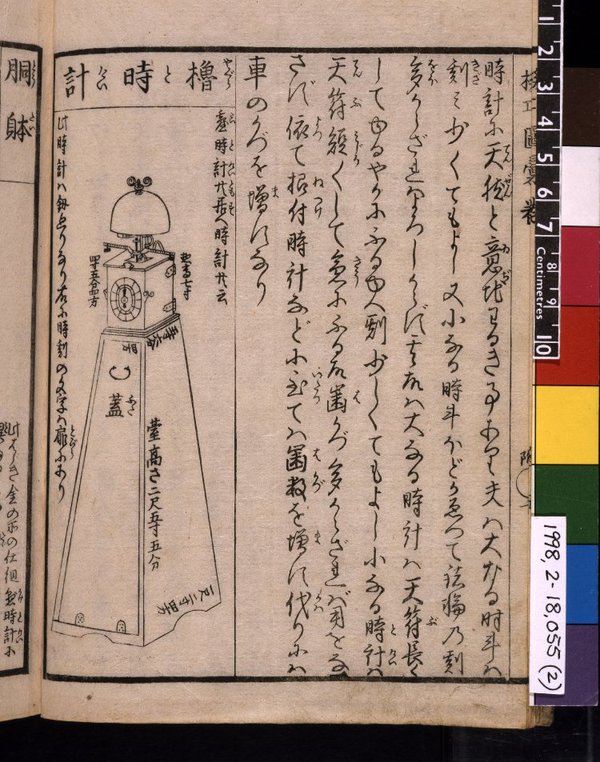

- the stand or lantern clock, weight-driven and either mounted on the wall or placed on a stand.

- the table clock, designed to be placed on tables or on a suitable place in an alcove.

- the pillar clock, specifically made to hang on the thin wooden pillars which made up the framework of the inner paper wall of the house.

In the early period, the oscillating foliot was used as the timekeeping element, a single one in the earliest clocks and a double in the later, more sophisticated examples. As the technology progressed, pendulums or oscillating spring balance wheels were used – a larger form of the device found in mechanical watches.

Such clocks were only owned by the wealthy and were perhaps more used as status symbols than they were to tell the time and organise the household.