If only I knew what the right time is

This post was written by David Thompson

When you want to know the correct time today, you either look at your mobile phone or you look at your radio controlled clock watch or listen to the six pips on the radio. However, don’t do the last one on digital radio as it is quite a bit out of sync with the real time – about two seconds.

Before the introduction of telegraph time signals and the distribution of time, everyone had to rely on a local observation of true solar time – that is, the time shown on a sundial.

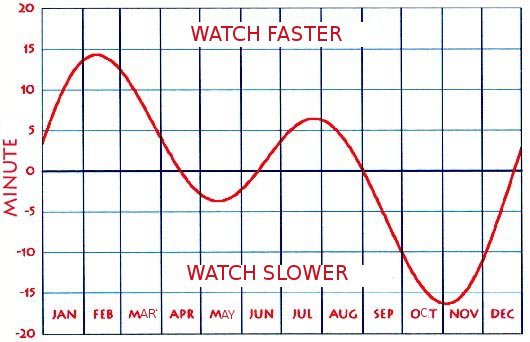

Unfortunately, the mean time shown by a clock and the true time shown by a sundial don’t agree throughout the year. Because the earth’s orbit around the sun is elliptical and because the earth’s axis is tilted to the celestial plane by 23 ½ degrees, the sundial (showing apparent or true solar time) and the clock (showing mean solar time) can be different by as much as 15 minutes.

There are four days in the year when the clock and the sundial agree with each other – 15th April, 13th June, 1st September and 25th December.

Until 1657 and the introduction of the pendulum, real time didn’t matter much as clocks were so inaccurate that the variations between true and mean time were irrelevant to all except astronomers.

The application of the pendulum to clocks made them capable of much more accurate timekeeping and the same was true when the balance spring was added to the watch in 1675 – measuring time to within a minute a week.

So, in order for an owner to put his clock right by a sundial, he had to know what the difference should be between his sundial reading and the time shown on his clock.

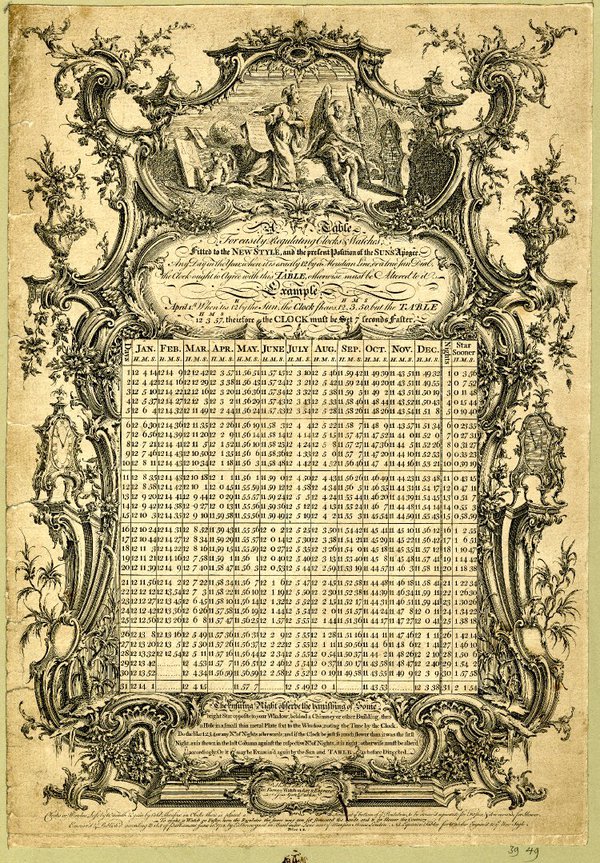

From the latter part of the seventeenth century, tables were published which gave exactly that information. The table shown here is devised so that when a clock is checked at noon, the table shows what time the clock should show.

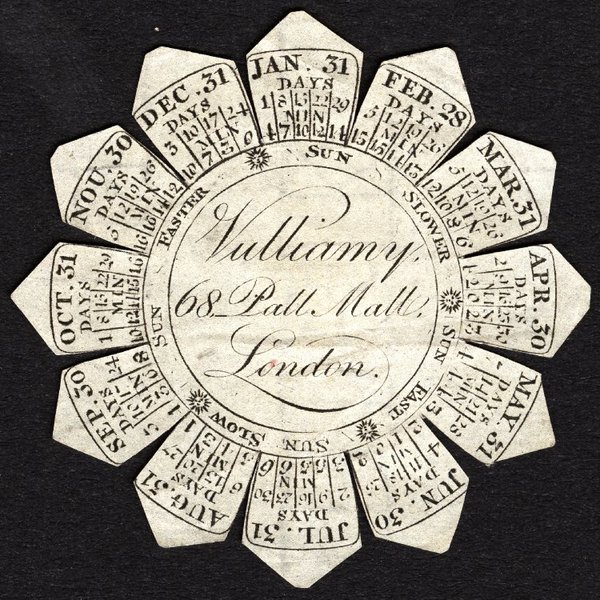

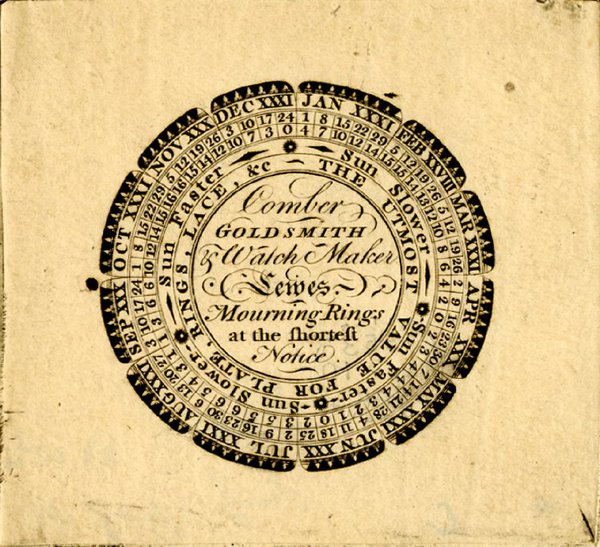

From the later part of the 18th century watchmakers would add a circular advertising paper into the outer cases of pair-cased watches and many of these had the equation-of-time table printed on them for easy reference.

Such papers were produced by top London makers such as Vulliamy in Pall Mall and by provincial makers such as Richard Comber of Lewes in Sussex. It was probably Comber’s customers who needed a table more than someone in the centre of London where the church bells offered a huge variety of ‘right’ time. It is worth bearing in mind, too, that the adjustments could only be done when the sun was shining!