Horological research

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Determined to ‘practice what we preach’, a number of us on the Council are currently involved in our own horological research; my project at the Royal Observatory Greenwich is the study of our enormous collection of marine chronometers.

The research will lead to the publication of a catalogue raisonne, ‘The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich’ in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the tercentenary of the passing of the great Longitude Act in 1714, and will form one of the series of Greenwich instruments catalogues published in recent years in conjunction with Oxford University Press.

All the timekeepers by the great John Harrison have now been fully dismantled, studied, photographed and researched (and put back together!) and I am now slowly working my way through the rest of the collection, from early examples by John Arnold up to the 4 orbit Hamilton, the rare Model 21 marine chronometer adapted to aid pacific navigation.

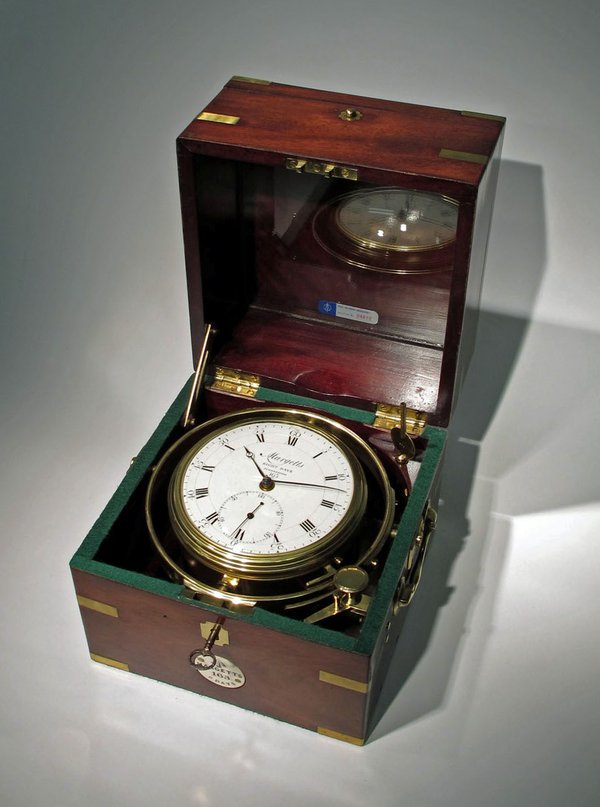

One of the great challenges for the catalogue is to write a ‘spotters guide’ to help collectors, dealers and curators with the tricky question of ‘how to date and evaluate your marine chronometer’. In the early years there were obvious differences in evolution and from one maker to the next, but, from the 1840s, marine chronometers appear, at first glance, to change very little through into the 20th century.

There are however many things to look out for, both in the movement and the box, which will enable a more sophisticated evaluation of a given chronometer. But be warned! These functional objects have often had considerable alteration and ‘upgrades’ over the years (lives depended on their being ‘up to date’, after all) and we should be prepared to accept, and dare one say rejoice in, instruments with a complex history. Later posts may expand on this interesting aspect.