Having a smashing time

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

On my twelfth birthday I was given my first watch.

I remember that it had the word ‘shockproof’ stamped on the back and that I wondered just how ‘shockproof’ it was. Mercifully I did not try to determine the limits of what it could take.

On Wikipedia I find that ‘shockproof’ should be understood as ‘shock resistant’, and that there is an international standard which specifies the minimum requirements and describes the corresponding method of test.

It is based on the simulation of the shock received by a watch on falling accidentally from a height of 1m on to a horizontal hardwood surface.

In the test the shock is usually delivered by a hard plastic hammer mounted as a pendulum. Some manufacturers are more ambitious.

Under the heading ‘Having a smashing time: Making sure your watch stands the test of time’ a newspaper article describes and illustrates the many types of torture to which the Swiss factory of IWC (International Watch Company) subjects its timepieces.

The impact test is illustrated here with images from the article. A metal pivot, weighted with a 10kg block, is pulled upright, then swings round to hit a watch held in a vice. A cotton sheet is laid out to catch the watch, and technicians check after each impact to see that it’s still ticking perfectly.

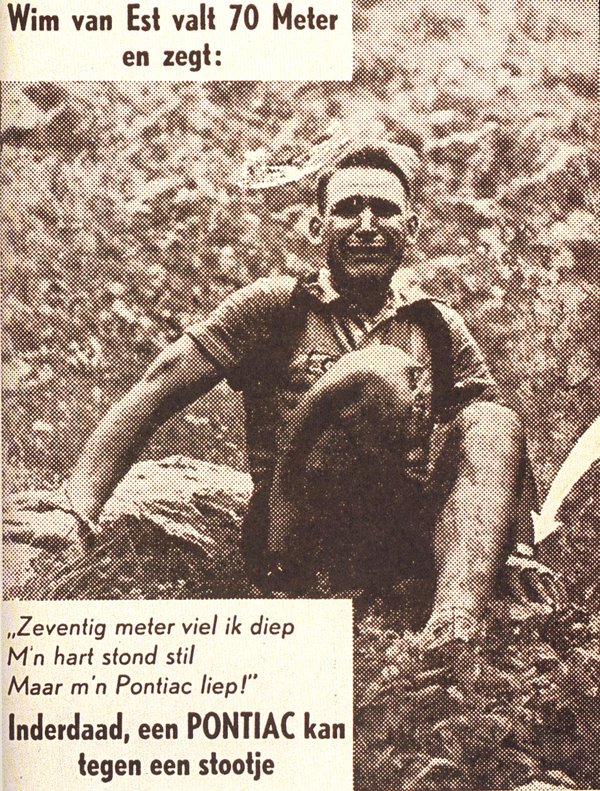

A less carefully planned demonstration of the shock resistance of a watch was given during the 1951 Tour de France, the annual cycle race.

The watch manufacturer Pontiac had sponsored the Dutch team by supplying them with wristwatches. One runner fell and dropped seventy meters down the side of the mountain.

Amazingly, he was not seriously injured. Even better for the sponsor, his watch was still ticking. Pontiac made a successful publicity campaign out of it.