Backwards and forwards

This post was written by James Nye

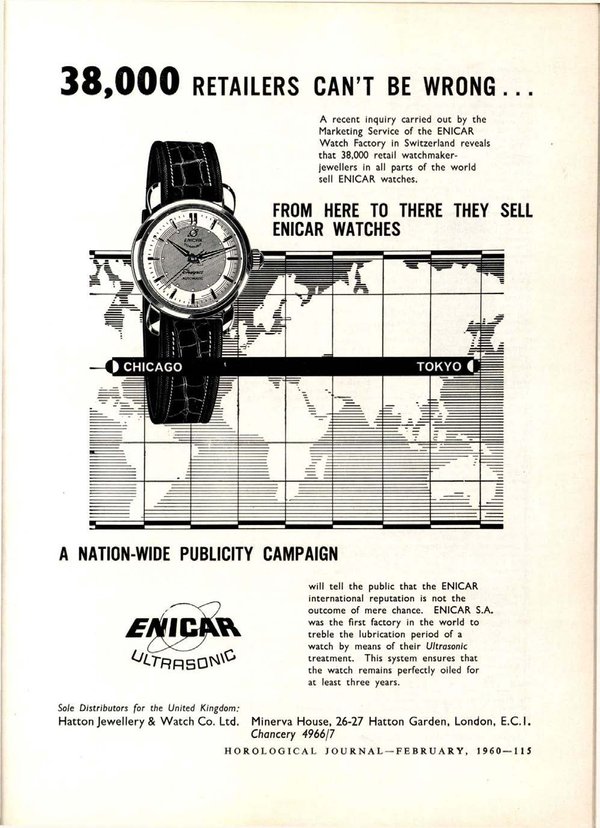

I am shocked to realise it is now a decade since I blogged about Enicar watches. As collectors know, Enicar derives from reversing the family name of the owners, Ariste and Emma Racine. Signing clocks and watches like this has a long tradition, with an interesting variety of explanations.

Back in the December 1993 issue of Antiquarian Horology, Sebastian Whitestone discussed some watches that bogusly claimed a London origin, but which in reality were from the Friedberg region and signed Lekceh, Legeips, Rengaw, Renpuarg and Ysorb. Reverse these and we have the less exotic Heckel, Spiegel, Wagner, Graupner and Brosy.

Mirrors reverse images, and tellingly, Spiegel also used the giveaway signature Miroir, London. The word ‘spiegel’ is German for mirror, and thus another pun.

But not all Friedberg makers reversed their names when they added a London location. Eckert and Schreiner signed (falsely) from London, but used their normal names.

Surveying the Ashmolean Museum's watches in the December 2000 issue of AH, David Thompson enlarged the geography, tying a watch signed ‘Renpuarg, London No. 4’ to Augsburg.

Alice Arnold Becker revisited backward signatures in AH in June 2014, taking the line that it was all marketing. The watchmakers perhaps falsified locations to secure the gravitas and caché of the London market – creative branding, familiar today.

Dutch horologist John Selders has also studied this phenomenon, publishing several pieces in Tijdschrift and summarising in 2015 with a list of 24 such reversed names, from the late seventeenth century to the turn of the nineteenth, and noting that some makers signed from Paris, not just London.

Strangely, precisely the same thing happened in Britain. English and Scottish makers of watches also reversed their names. An example is a watch by James Peddie of Stirling, signed on the back plate Jas Eiddep (see Clocks, April 2019). More prolific is Eardley Norton, whose signature Yeldrae Notron appears with surprising frequency. Usher & Cole’s apprentice John Wontner later signed objects as Rentnow. Cole signed as Eloc.

What on earth were all these people doing? There are several theories. Some assume distant makers wanted to capture borrowed prestige, and value, by signing from London, or Paris – an element of passing-off. A false signature disguises true authorship.Some suggest it was done to avoid taxes. Perhaps it limited redress to a real maker. Or perhaps it shows the maker’s sense of humour?

Does it all echo the original Rolex/Tudor division – an affordable product from the same stable, but differentiated?

No firm conclusions are possible, but some theories are surely too far-fetched. Tax officials won’t be fooled by mirror-writing. Signing a watch carries a maker’s chosen identity out into the world, and should be permanent, and memorable. A sense of whimsy could be involved, maybe even a sense of a brand that stands on its own, distinct from the name of the controlling mind involved.

In all, a subject that deserves more than a backwards glance... and if anyone has any other examples of reversed clock and watch signatures, please do tell me!