A sad commemoration

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A couple of weeks ago, I attended Bob Frishman's NAWCC conference on 'Great Horological Collectors' at the Horological Society of New York's home in New York City – a wonderfully successful and interesting event. By good fortune the date of the conference came just before a short holiday we had planned in New York, with passage home on the Queen Mary 2 – a delightful way to cross the pond.

When planning the trip I realised that, by a rather extraordinary coincidence, during the transatlantic crossing there would occur the 80th anniversary of a family tragedy, played out in those very waters.

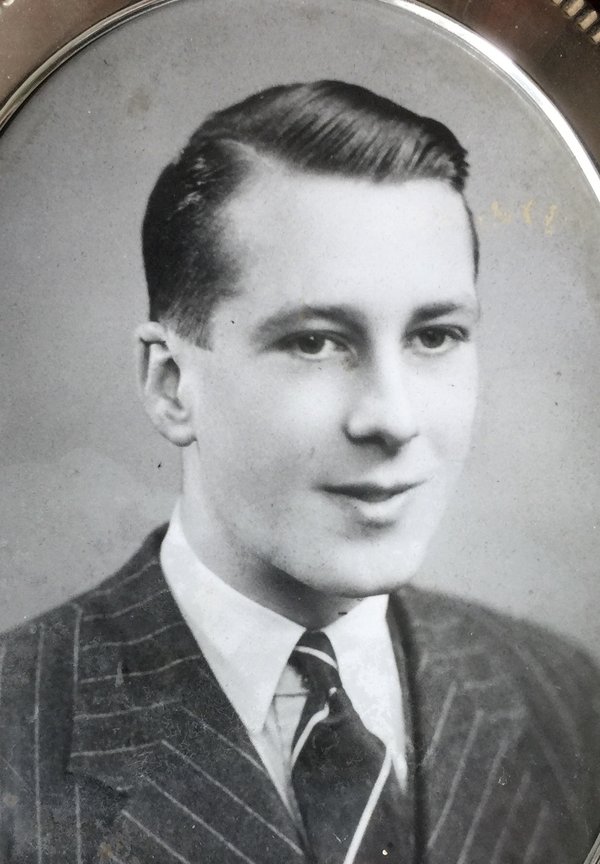

My Uncle Pat – my mother's brother – was serving on a merchant troop ship, the MV Abosso. On the evening of 29 October 1942, when the ship was travelling alone in the North Atlantic, it was torpedoed by a U-boat and sunk. 362 of the 393 passengers and crew lost their lives, including Uncle Pat, who was just 23 and had married only a few weeks before.

Just one lifeboat survived with 31 souls to tell the tale, some of them Navy officers who were aware of the detail of what happened.

The reason for telling this sad tale in an AHS blog is that there were two critical horological elements to the tragedy.

About 6 p.m. that evening, the master of Abosso, Captain Reginald Tate, became aware the ship was being tailed by a U-boat – U575, commanded by Kapitan-Leutnant Gunter Heydemann (1914–1986), as it turned out. The ship's crew was able to detect the submarine using ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) echo-sounding to determine the sub's bearing and distance, the latter by using an ASDIC chronograph.

The watch has a high frequency sweep-seconds hand on a dial recording up to six seconds, the time between transmission of the sound pulse and the echo determining the distance of the sub from the ship.

Having established precisely where the sub was, the ship's master had to decide what to do.

An option was to go full steam ahead and try to out-run the submarine, which would normally be possible – a submerged submarine makes much slower progress, though at a maximum speed of 14.5 knots, the Abosso was not a particularly fast ship.

The alternative was to adopt a 'random' zig-zag course so the U-boat could not predict the ship's position accurately enough to make it worth firing torpedoes at it, though zig-zagging naturally slowed down the progress of the ship considerably. The practice did generally work well, if maintained long enough, as U-boats had limited quantities of fuel and eventually had to head off for a rendezvous for refuelling.

Deciding not to try and out-run, but to zig-zag, the Abosso brought into action its zig-zag clock, a part of the navigational equipment on the bridge of WW2 merchant ships at the time.

A fairly standard ship's bulkhead clock is adapted to have an electrical contact at the tip of the minute hand, and round the periphery of the minute track on the dial is a metal ring with a number of moveable electrical contacts.

Each time the minute hand touches a contact it closes a circuit and a bell rings in the wheelhouse informing the crew to change course one way or the other.

If in convoy with other ships it is of course vital that all the ships adopt precisely the same agreed pattern of zig-zags, and when the instruction to zig-zag is given, the whole convoy would be signalled a secret code for the pattern to be used. The contacts on all the ships’ clocks would then be adjusted accordingly and zig-zagging would begin at a specific time, thus foiling the U-boats' attempts to align torpedoes with a target ship.

The log of U575 has survived, so we can also follow what happened from the U-boat’s perspective. Heydemann, a much decorated Commander in the ‘Brandenburg’ wolfpack in the North Atlantic, sighted the Abosso about 6 p.m. that evening. He was running low on fuel but decided to try and attack. Realising he was being traced, he went deep, out of reach of the ASDIC, but followed from a distance until he was nearly out of fuel. At that point, thinking they had lost the sub, Abosso’s master made the fatal decision to stop zig-zagging. Realising this, Heydemann risked running out of fuel and moved closer to the ship to attack.

Reading the U-boat's log today, and comparing with the U-Boat Commander’s Handbook (available as a translated reprint as E. J. Coates (translator), The U-Boat Commander’s Handbook, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, 1989) one discovers this was a textbook operation.

At 22.13hrs, Berlin time, one of the middle torpedos of four directed at the Abosso in a fan pattern struck the ship virtually amidships. The U-boat surfaced to inspect the target and Heydemann recorded seeing lifeboats being launched. One more torpedo was fired into the ship to deliver the coup de grace, and about half an hour later Abosso sank, U575 then departing to rendezvous for refuelling.

The one lifeboat which survived was picked up on 31 October by HMS Bideford, one of a convoy forming part of 'Operation Torch', heading for North Africa but, in the heavy seas at the time, no other lifeboats or survivors were ever found.

On the evening of 29 October this year, exactly 80 years later, and as close to the location of the Abosso’s sinking as I could estimate, I sneaked a centrepiece flower arrangement from our table after dinner and, against Cunard’s strictest rules, cast them into the sea at the stern of the ship.

A timekeeper had shown Abosso where the danger was, and the other timekeeper should have saved them. It is a sad thought that if only Captain Tate had left his zig-zag clock running just a little longer, the U-boat would have had to leave and 362 lives would not have been lost.

R.I.P. Uncle Pat.