War time reflections

This post was written by James Nye

The June centenary of the Archduke’s assassination is behind us, though in July 1914 no one imagined a world war breaking out a month ahead (head to the LMA for a great new exhibition).

In May, my talk at Greenwich—‘Bang on Time’—focused on 1940s clockwork devices used for delaying explosions, and it seems quite a few of my blogs dwell on bombs and destruction. Today, I reflect on some horological titbits from the Great War.

For a start, patriotism (and then conscription) emptied out light engineering and clockmaking firms of their young workers.

Of the 450 staff at Smith & Sons (MA) Ltd, floated in July 1914, nearly 10 per cent were at the Front a month later.

Silent Electric’s Herbert Bowell confirmed to the authorities in March 1917 that all his employees had signed up in 1914.

His better-known brother George, by contrast, was a munitions worker—the path for many other craftsmen.

After the ‘Shell Crisis’ of May 1915, resources poured into shell and fuze-making capacity, with the result that millions were crafted, to be fired on the battlefields of Europe. Though military demand for chronometers and timekeepers of all sorts mounted rapidly, clock and watchmakers from Clerkenwell were packed off to the north-east to work in firms such as Vickers, to manufacture fuzes.

While the factory workers and the soldiers they supplied are long gone, their products endure.

A standard artillery fuze might delay firing the main charge by up to half a minute. Precise (and expensive) fuzes had a clockwork escapement (see video) while vast numbers were simply igniferous, though even then involving a dozen or more precisely machined parts.

These remarkable engineered brass mementos regularly emerge from the soil a century later, and will still strip down.

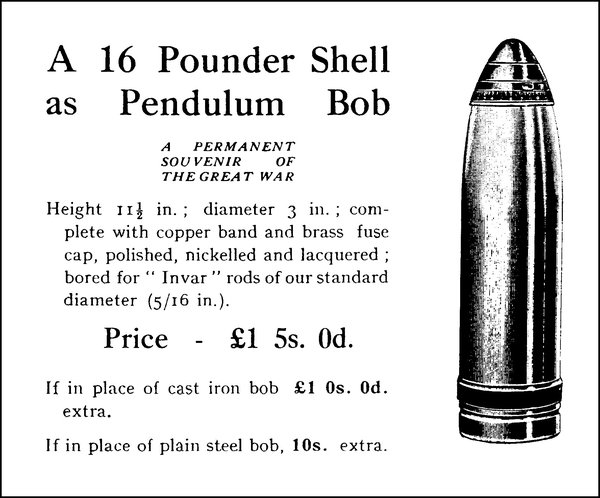

While surplus shell cases formed myriad household ephemera for years – Trench Art – another astonishing survivor was courtesy of the clock trade itself, in an idea from the irrepressible Frank Hope-Jones, who purchased 16-pounder shells (and fuzes), offering these as a pendulum bobs—a ‘souvenir’ of the Great War. What a blast!