The AHS Blog

An eighteenth-century wind-up

This post was written by James Nye

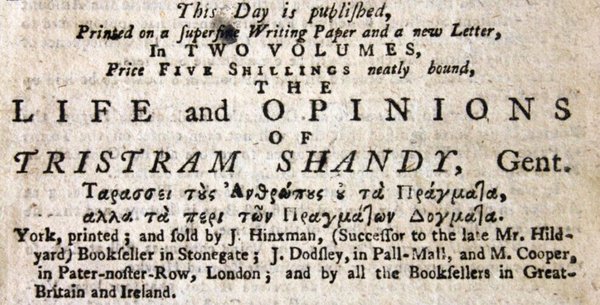

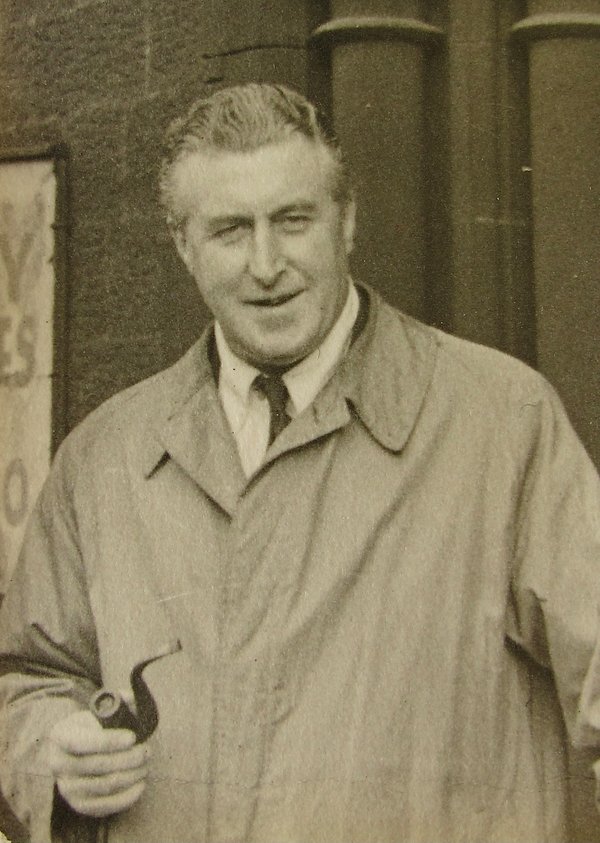

Perhaps an AHS blog post is an unusual place to find literary criticism, but the recent death of Dr Bill Linnard, a much-loved horological scholar, calls to mind his treatment of a risqué horological joke at the opening of Laurence Sterne’s Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (see Horological Journal April 2014, pp. 174–5).

The narrator, Tristram, describes his father as a man of unshakeable and timely habits, winding ‘a large house-clock, which we had standing on the back-stairs head’ on a monthly basis, and, we are to infer, making love to Mrs Shandy on a like schedule. At the moment of Tristram’s conception, the earth does not move as expected: ‘Pray my Dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?’

The book seemingly met with general outrage owing to its saucy content. As Linnard noted, the Clockmakers’ Company and the wider horological trade were apparently among the most offended, a small group of them publishing The Clockmakers Outcry Against the Author of the Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (J. Burd, London 1760).

In this pamphlet we learn that sex-workers in London had come up with a new opening gambit. ‘Nay, the common expression of street-walkers is “Sir, will you have your clock wound-up?”’ As a result, clocks had become taboo and orders were cancelled, much to the chagrin of the trade. Timepieces were now viewed ‘as obscene lumber exciting to acts of carnality’.

Bill Linnard described the pamphlet as a spoof, but many conclude that Laurence Sterne himself was the author, engaged in a tradition of puffery by publishing criticism of one’s own work – there being, after all, no such thing as bad publicity. We can be confident the clockmaking trade did not actually suffer at all, and there is, rather regrettably in retrospect, no other known reference to gentlemen being asked if they wanted their clock winding.

OK. We can see through Sterne’s elaborate artifice in stirring up further interest in his own work, but what was his inspiration? This is the question we clockmakers need answering. Why might Sterne have delved into the world of clockery, and on such a bawdy basis?

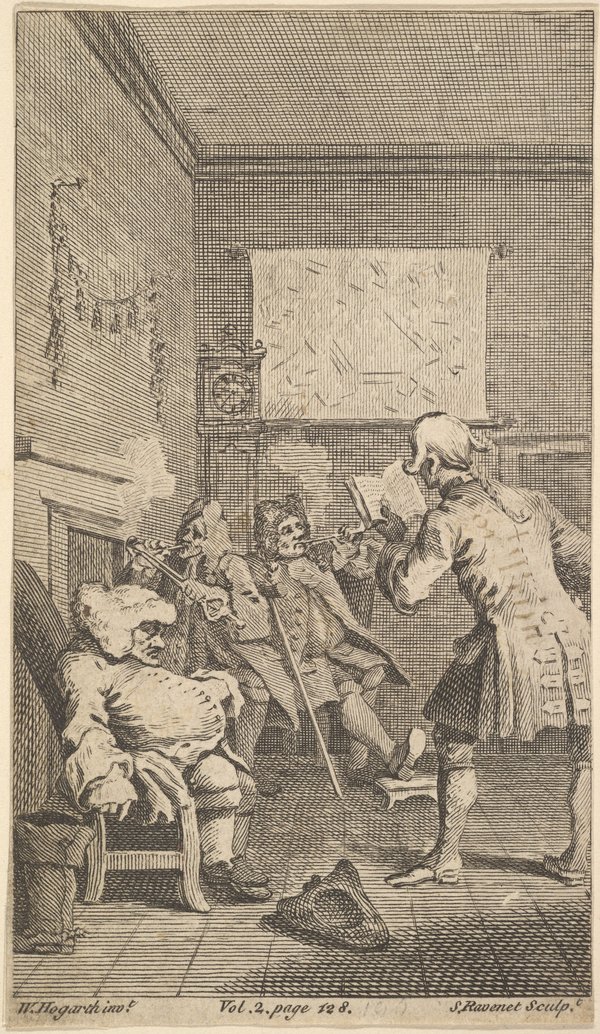

A possible answer lies in his friendship with William Hogarth, who provided illustrations for Tristram Shandy. As Patricia Fara amply demonstrated in her AHS London Lecture on ‘Hogarth: Time’s Artist’, in January 2023, the imagery and symbolism of clocks were subsumed throughout Hogarth’s work. Clocks were part of an attempt at rationalisation and control, but also stood for the frailty of humanity. Hogarth was also no stranger to conjuring images of the seedier side of life.

A month-going clock was no common item in the mid-eighteenth century – it was an expensive luxury, or a natural accessory for an enlightened gentleman, a sort of exquisite machine to bring order amid potential chaos. Someone close to Sterne had one, we have to assume. And since it was in his nature to satirise or parody such attempts to impose control, the clockmakers came in for some unlucky wind-up humour.

Playing card packing pieces

This post was written by Tobias Birch

As some of you might know I am passionate about Thomas Mudge. So in June 2023 I was delighted to be invited by the curator of horology at the British Museum, Oliver Cooke, along with esteemed horologists Andrew King and Jonathan Betts, to look at two Mudge clocks, the Lunar Mudge and the Polwarth Mudge.

Jonathan was researching for his upcoming talk to the AHS, 'The Technical Legacy of Thomas Mudge'. While inspecting the ebonised case of the Lunar Mudge, a case that is, I believe, the beginnings of the three pad top style case table clocks you see in the second half of the eighteenth century, I decided to remove the seatboard. You never know what you might find!

On removing the seatboard, made more involved as one had to first remove a brass carrying handle, the effort was soon rewarded.

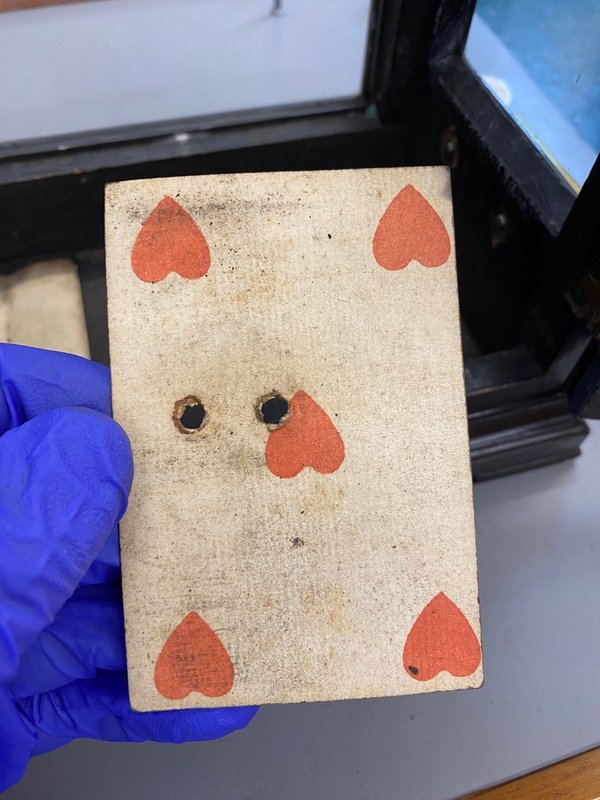

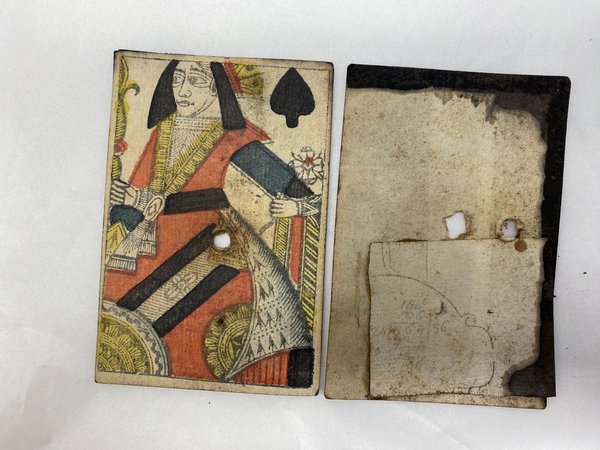

To all our surprise, hidden beneath the seatboard I found some playing cards, and not your everyday, free in Christmas crackers playing cards. They were a well preserved hand-painted Queen of spades and a five of hearts. Most likely eighteenth century playing cards.

The cards were placed under the seatboard, as convenient packing pieces to raise the movement slightly, probably when the clock was originally made in the 1750s. After photography I placed them carefully back in the position from where they came.

This was the first time in over 30 years of working on clocks that I had seen playing cards used in this way, and I didn't expect to see it again. Yet, less than a year later, while working in my own workshop on a Thomas Mudge and William Dutton table clock of the three pad top style that I mentioned earlier, made around twenty years later than the Lunar Mudge, I once again did my usual practice of removing the seatboard. This was more easily done this time, as there was no handle to take off first.

You have no doubt guessed what I found.

Here the cards were folded over and held in place with small round head brass nails. The left card was too indistinct to make out the suit, the card on the right is a two of spades. Again, hand painted on similar colour card as the Lunar Mudge cards.

I would be interested to hear from anyone that has found similar playing cards placed under seatboards of table clocks. Perhaps there was an avid card player in the Mudge workshops and they used cards from incomplete decks they had lying around? Or perhaps they used cards from a deck that had proved unlucky and they no longer wanted to play with?

We will never know, but I liked the link back to an individual, long gone, whose work survives and who, if I were to somehow meet, would, I imagine, have plenty to talk about.

Time symbols in cemeteries

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My wife and I like to visit cemeteries. To some this may seem a morbid pastime, but we value their tranquillity, and appreciate them as a kind of open-air museums where we see how our ancestors commemorated their dead.

In Lisbon is the enormous hillside Cemitério do Alto de São João (Height of St. John Cemetery), overlooking the river Tagus. Opened in 1833, this vast necropolis is mostly filled with family tombs and mausoleums, lining what they call ‘ruas’, ‘streets’.

On gravestones and funerary monuments, you often see the hourglass as an emblem of mortality, a symbol of the passing of time. Often there are wings at the sides, reminding us that time flies and eventually will run out for all of us.

The Cemitério do Alto de São João contains many examples of these winged hourglasses, often in combination with other symbols of death, such as the scythe of Father Time, an inverted torch symbolising the extinction of the flame of life, or a skull and crossed bones.

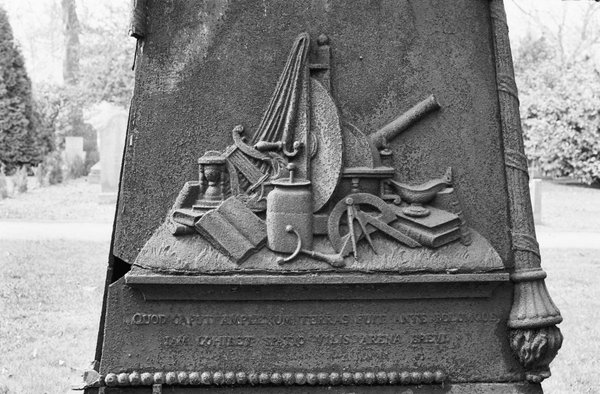

An hourglass is also depicted on a cast-iron funerary monument erected in 1832 on a Dutch cemetery, together with an oil lamp, symbol of eternal life, seen standing on a book on the right. The lamp is also shown prominently on a design drawing for this monument and there are also inverted torches on the monument, as can be seen here.

The hourglass and the lamp are mixed in with an elaborate ensemble of scientific instruments (a single-plate electrostatic generator, with a Leiden jar and a discharger in front, a telescope, and three drawing instruments), which commemorate that the deceased man had a strong interest in the natural sciences, and owned his own collection of scientific instruments.

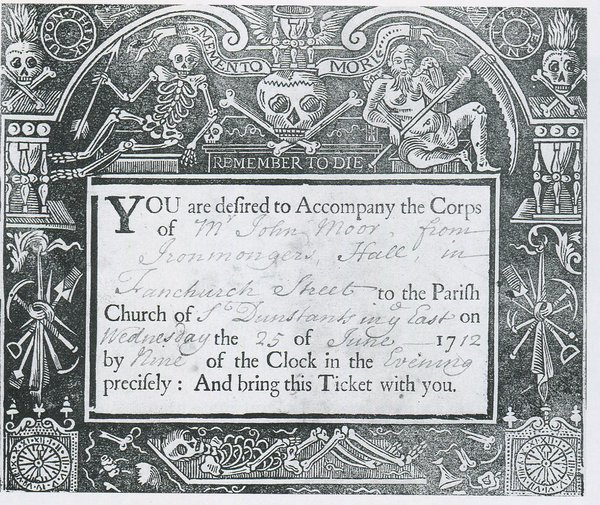

On a printed invitation to attend a funeral, dated 1712, we see three hour glasses, one of them winged. But there are also, in the bottom corners, two clocks, another reminder of the passing of time.

On our visits to cemeteries, we have only once found a clock depicted on a gravestone, where it was part of the instrumentation of the deceased, the German astronomer C. L. C. Rümker (1788–1862). This was also in Lisbon, in the British Cemetery, and it was shown in an earlier blog, Clocks in Lisbon.

But in the Cemitério do Alto de São João we found something we had never seen anywhere else: the depiction of a clock dial.

The hands are in the classic ‘10 past 10’ position, and the dial is accompanied with a sobering text that translates as ‘The hours go by / the days go by / the years go by / and our lives go by’.

And as if that were not clear enough, at the bottom is again the winged hourglass.

Unless otherwise stated, photos by Jade de Clercq.

Who was Master Humphrey?

This post was written by James Nye

Sometimes I'm asked about my lifelong obsession with clocks and what on earth I see in them – or perhaps what they say to me.

In reply, I'll comment about their longevity and the fact they tend to last longer than people. I'll observe that they tick out the lives of those around them – that they are observers in whom the events they witness become inextricably bound up.

And I'll say that sometimes, when we are researching or writing about those subjects, our clocks help us along with helpful nudges and hints.

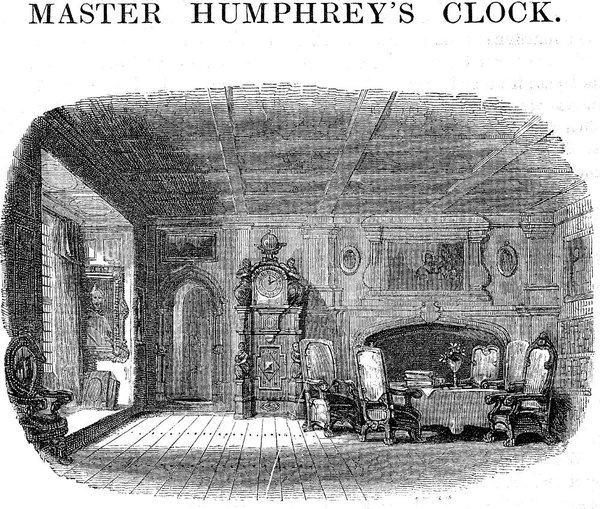

It pleases me to know that Charles Dickens had something of the same sense. In Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840), the eponymous timepiece is imbued with the same timeless and comforting qualities.

Discussing the work with a friend, Dickens describes a quaint old character who has a great affection for a clock:

"He has got accustomed to its voice, and come to consider it as the voice of a friend […] its striking in the night has seemed like an assurance to him that it was still a cheerful watcher at his chamber door […] its face seemed to have something of welcome in its dusty features, and to relax from its grimness when he looked at it from his chimney corner."

Not very practically, Dickens had the notion that the trunk of the clock could be a safe repository for the manuscripts of a club that would meet to read to each other. He says:

"I mean to tell how that he has kept his old manuscripts in the old, dark, deep, silent closet where the weights are, and taken them thence to read (mixing up his enjoyments with some notion of the clock), and how, when the club came to be formed, they, by reason of their punctuality, and his regard for this dumb servant, took their name from it."

The Horological Journal of October 1912 (available online to AHS members) carries a pleasing account of Dickens’s inspiration.

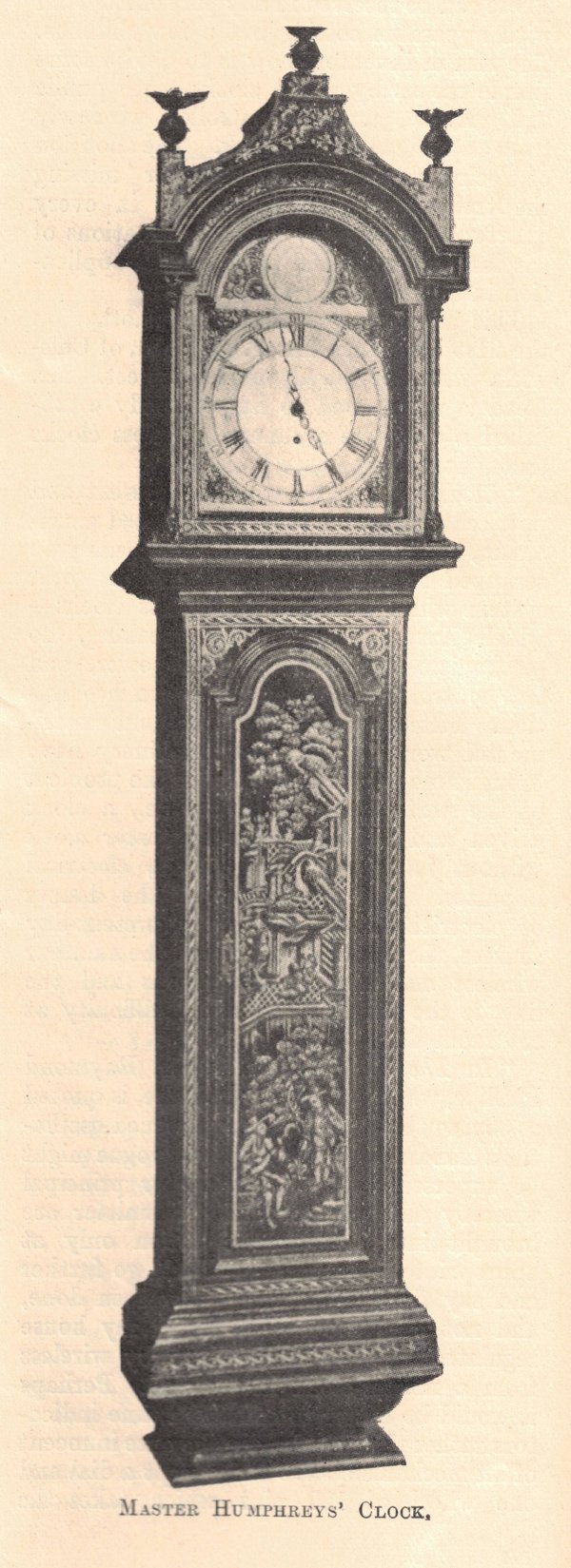

In 1837, Dickens spent several weeks in Barnard Castle, Yorkshire, researching school conditions for Nicholas Nickleby. While there, he encountered a clockmaker named William Humphreys.

In 1828, Humphreys had acquired an ornamental seventeenth-century Dutch longcase clock with a worn-out movement. The following year, having fitted it with a new mechanism, he installed it in a niche to the right-hand side of his shop door.

This was the real "Mr Humphreys' clock," consulted occasionally by Dickens on his local journeys. He came to know not just the clockmaker himself but his son, Master Humphreys. In Dickens's mind, "Humphreys" became "Humphrey," and thus was born the inspiration of his 1840 work.

And as I type, I am accompanied by a comforting tick from a shelf just beside me. If I wait a few more minutes, I will be reminded of the hour...

To Gaddesden (on the trail of a turret clock, part 2)

This post was written by Dale Sardeson

In a recent post, On the trail of a turret clock, I began an account of my search for a clock by Allam & Caithness. Informed by the Thwaites archive transcription and investigation project that James Nye and Keith Scobie-Youngs have been working on, the trail led me to St. John-the-Baptist church in Great Gaddesden, Hertfordshire.

The website of the church reveals that indeed, their clock was given to them by Gaddesden Place in 1955.

Another pointer from James Nye directed me to the website of Gaddesden Place, a house no longer in the Halsey family. From there I made contact with the current owner, who directed me to the following two photos of the North Wing, taken in 1898 and 1926 respectively. You can certainly make out the shape, if not the detail, of a clock dial above the main entrance to the wing.

The wing was demolished in 1955 owing to dry rot, and it was then that the clock was given to the parish church, with which the Halsey family have a long and close relationship.

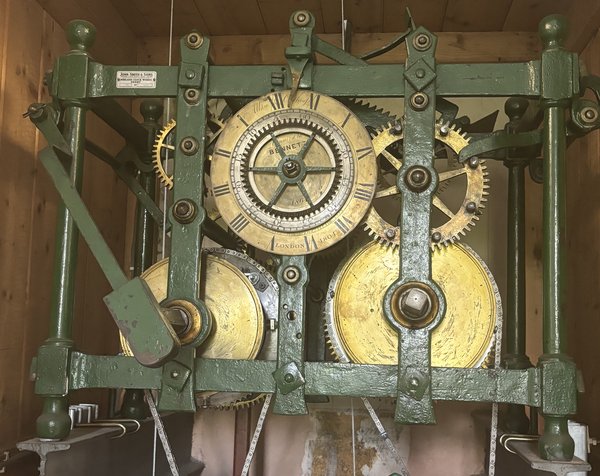

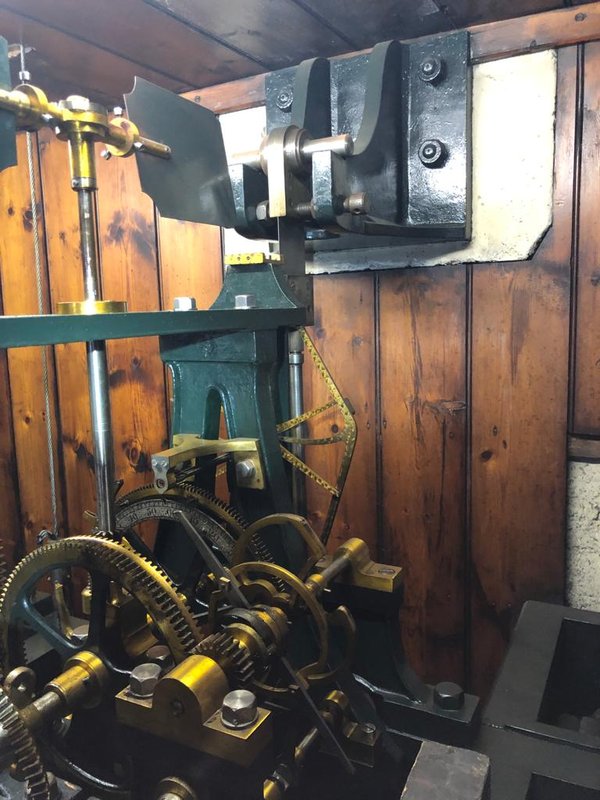

I arranged a visit to the church, and one of the wardens, Peter King, kindly showed me into the tower. I was able to have a good look at the clock. It is an example of what Keith Scobie-Youngs has described as Thwaites’s ‘Ford Model T’ of turret clocks, with rack striking, gravity-arm maintaining power, and a recoil escapement with steel pallets affixed to a cast brass pallet frame, all housed within Thwaites’s characteristic green frame. It is signed for Allam & Caithness on the setting dial.

Besides the features of its construction, looking at the clock in person allowed me further glimpses into its history.

There are two inscriptions on the setting dial: ‘Repaird by Bennett 1864’, and ‘Cleaned & rebushed by J Steptoe 1925’. The latter would almost certainly be James Steptoe of 67 High Street, Hemel Hempstead, found listed as a watchmaker in a number of Kelly’s Directories for Hertfordshire through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Bennett, however, is harder to place, being such a common name. It would be tempting to think it could have been Sir John Bennett of Cheapside – after all, it was a London firm rather than a local one whom the Halsey family had first commissioned for the clock’s supply. But there were several Bennetts in London it could have been at that time.

There is also a John Smith & Sons service plaque from 1955, so it appears it was they who carried out the installation of the clock into its new location at the church. Smith of Derby have continued to be involved in the care of the clock, fitting it with autowind units in 2016.

It is quite a joy to be able to trace a clock from its original written estimate right through to the present day, and I can’t wait to see what other stories have been revealed from the Thwaites Daybook project!

Unfriending in the eighteenth century

This post was written by James Nye

Recently, AHS member Jeremy Evans, a highly distinguished former horology curator at the British Museum, donated a remarkable archive of research papers to the Society. It was amassed over a long career and fills four metres of shelves at our Lovat Lane headquarters. It was most generous of Jeremy, and we were delighted to receive it!

While waiting for the papers to be catalogued by our Archivist, Dorota Pomorska, I decided to have a bit of a delve. In an index of horological articles that Jeremy had found in eighteenth-century newspapers, I noticed the entry ‘Matrimonial Strife’. Curious, I looked further.

Usually, during a male clockmaker’s life, his wife is invisible in the historical records. Sometimes, though, these women do make appearances. Elopement could be the cause. It is now customary to think of elopement as the young running away to marry without parental consent. Yet in the eighteenth century, married women also eloped – from their husbands. Sometimes this was with a lover. The word could also mean ‘escape’.

In a world of sexual inequality, women had few options. Maureen Waller, in her work The English Marriage: Tales of Love, Money and Adultery (John Murray, 2009), wrote, ‘On her wedding day, a woman stepped into the same legal category as wards, lunatics, idiots and outlaws’.

One reason why women left their husbands was domestic violence. Abuse of a spouse is well-exemplified in the cruel treatment meted out to Dorothy Arnold by her husband John, of chronometer making fame and usually a horological hero, detailed in Martyn Perrin’s article ‘The secrets of John Arnold, watch and chronometer maker’ (Antiquarian Horology, June 2015).

In other cases, we do not know the underlying reason why women left their husbands and can only speculate.

In Jeremy’s archives was the following list of horological escapees:

- Sarah the wife of William Gibbs of Upper Moorfields, clockmaker (Daily Advertiser 27 June 1741).

- Mary the wife of Edmund Pottecary, clockmaker, of […] St. Andrew Holborn (Daily Advertiser 6 August 1745).

- Sarah, the wife of Thomas Linter, watchmaker of Cripplegate (Daily Advertiser 6 August 1746).

- Elizabeth, the wife of John Simmons, watch-case maker in St Bartholomew’s the Great (Daily Advertiser 11 September 1746).

- Thamisian Symonds, wife of John Symonds, watch-case-maker in St Martin Ludgate (Daily Advertiser 20 May 1747).

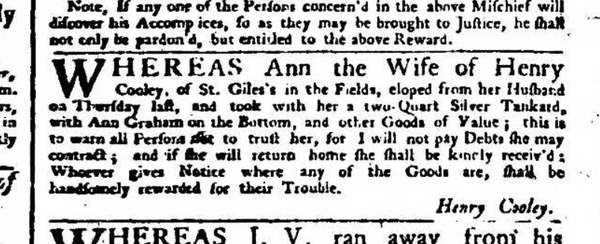

- Ann, the wife of Henry Cooley, clockmaker of St Giles’s in the Fields (Daily Advertiser 11 May 1748).

- Rachel, wife of James Webb, clockmaker in Bristol, who ‘lives an irregular life’ (London Gazette 21 February 1761).

- Mary, wife of John Lowder, clockmaker and mariner of St Botolph’s, Aldgate (General Advertiser 7 October 1749).

Each announcement followed a more-or-less standard form of words — essentially, ‘This is to warn all persons not to credit, trust, or lend any money to...’ and further ‘I will not pay any debts she may contract’.

It’s obvious why husbands chose to make their news so uncomfortably public. At heart, it was damage limitation, though Mr Azier, watchmaker, seems to have been unlucky. He was pursued for a debt of £150 run up by his estranged wife for ‘Velvet, Damask Cloaths, Diamond Rings, Gold Watch etc’. On that occasion, the court ruled that ‘none in this case could justify the giving of credit to another man’s wife, for more than necessaries for food and apparel, but not for superfluities like those.’ (Caledonian Mercury 5 July 1725). For whatever reason, whether justified or not, Mrs Azier seems to have sought a way to punish her husband.

The AHS Women and Horology project is advancing our knowledge of the roles that women have played in the story of time. Do contribute if you can!

On the trail of a turret clock

This post was written by Dale Sardeson

Many readers will no doubt be aware of the Thwaites archive transcription and investigation project that James Nye and Keith Scobie-Youngs have been working on for the last few years.

As part of my own research into the turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Bond-Street watchmaking partnership Allam & Caithness, I asked James if he would look into the Thwaites documents for me and see what he could find pertaining to the pair.

I knew there was bound to be something, because in the Society of Antiquaries in London there is an Allam & Caithness table clock with a stamped Thwaites movement. I just didn’t know what or how much else the archive might reveal.

The period of daybooks that Keith and James have transcribed runs from 1780 to 1798, finishing three years after John Allam and Thomas Caithness went into partnership. With no Allam & Caithness entries in the daybooks for this period it appears that the pair did not have anything made for them by Thwaites during their first few years of trading, though unsurprisingly the partnership of William Allam (John’s father) and Thomas Clements did turn up a few entries in the transcribed period.

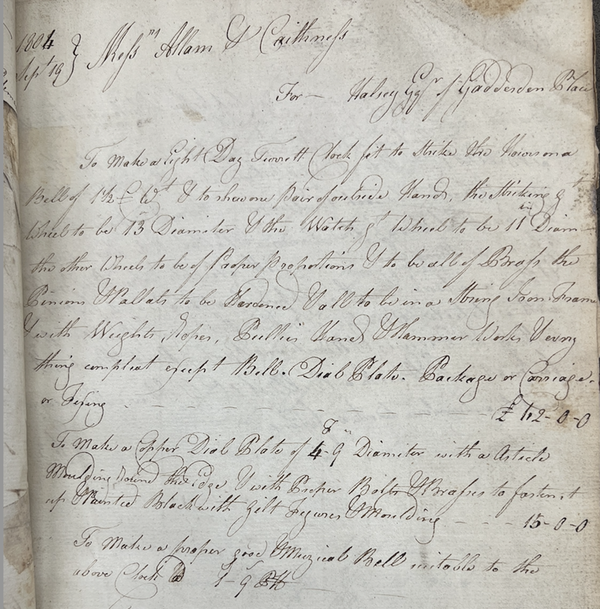

Undeterred though, James located a handful of pages from the Thwaites estimate book in the early 1800s pertaining to Allam & Caithness. All for turret clocks, among them was the following, dated September 1804, for an eight-day turret clock to be supplied for the Halsey Estate at Gaddesden Place in Hertfordshire.

James kindly did a search of the turret clock database and found that an Allam & Caithness turret clock is in St. John-the-Baptist church in Great Gaddesden, just down the road from Gaddesden Place...

...so to Gaddesden we must go.

To be continued.

Time to count our blessings

This post was written by James Nye

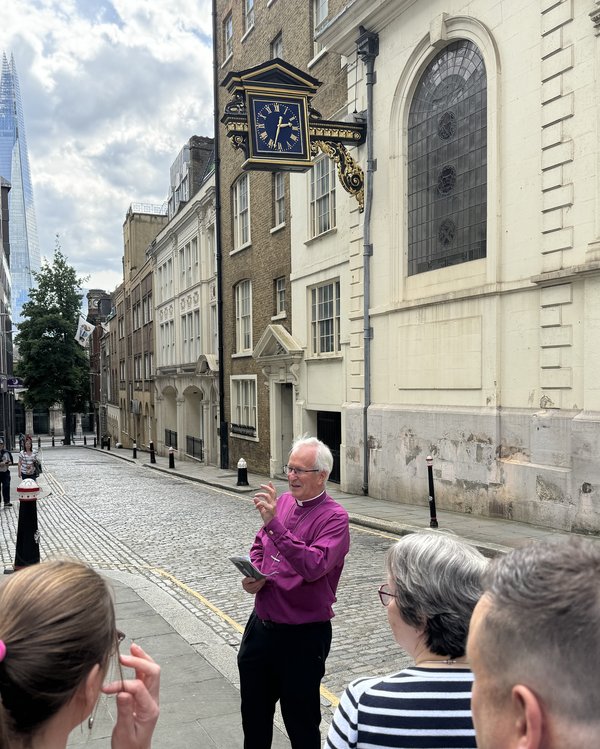

On Thursday 11 July 2024, a band of ten AHS members joined an unusual service conducted by the Rt Revd David Urquhart, assistant curate at St Mary-at-Hill, the church opposite our headquarters at 4 Lovat Lane and the venue where our London Lectures are held. It was for the blessing of the church clock, well-known in the City of London in part owing to the angle at which it sits (with a pronounced downward tilt), now stabilised with recent engineering interventions.

During 2023, the clock was scaffolded for some months to allow for conservation, new steel guyline supports, new leadwork, wood repairs, repainting, regilding, and more.

The church was rebuilt by Christopher Wren following the Great Fire, and survived the Blitz unscathed, but was severely damaged by a fire in 1988, after which its roof and ceiling required rebuilding. The original clock was possibly by John Wise, and the main external support timbers probably date from installation in the early 1670s. The clock gained a minute hand in the mid-1820s, but the original movement was later removed, perhaps in the mid-20th century, when a synchronous drive was installed. This reached the end of its life and was replaced in 2023 as part of the wider restoration project.

I visited the clock when Mark Crangle and Alex Jeffrey were finishing work for the Cumbria Clock Company. This included replacing the motor, fitting a new drive shaft, servicing the motion work and repainting the dials. There is a short film here

As we stood below the clock in the lovely afternoon sun, Revd David treated us to a reflection on the nature of time – the timelessness of much, yet the way there is so little time for anything when our lives are so frantic. He encouraged us to take to time to reflect, before leading a prayer for wisdom in using time, concluding with these words:

May this clock bring order to chaos and haste,

Mark joyous occasions and moments of grace.

Let it remind those who glance at its face

Of time’s precious gift, not a burden to chase.

We joined David and his fellow team members, plus priests from the local area, for a celebration back inside the church, where more photos of the clock restoration are on display – do take a look if you are passing by.

A time for sport

This post was written by James Nye

Since 2000, people have gathered each year in Mannheim-Seckenheim (Germany) one Spring weekend, ostensibly for an electrical horology fair, which over time has developed into a strongly social affair; a chance for distant friends to catch-up. In addition, a tradition has emerged for a small exhibition. This is the brainchild of one the two main organisers, Dr Thomas Schraven, known to many for his intense interest in, and knowledge of, the field of short-time measurement.

His research started with an in-depth exploration of the Hipp chronoscope, capable of measuring to 1/000th of a second, and used across many sciences. Much later his research into companies such as Löbner, Hammer and Zimmerman brought the uniquely German tertienuhr into sharp focus – a less expensive but useful device capable of measurements of 1/100th second.

Beyond the academic fields of science, short-time measurement has always been to the fore in sport, where records are established and determining close results may require the use of precision timing equipment. These days, it is easy to imagine all manner of electronic means for detecting and recording events, but a century ago the technology involved simpler analogue mechanics: the breasting of a tape in a race, the compression of a pneumatic hose below the tyres of a car, and so forth.

This year, Thomas mounted an exhibition centred around ‘Electromechanical Timekeeping in Automobile Racing’, including some pieces not seen in public before, and with the loan of a remarkable timing instrument from Stefan Muser of Dr Crott auctioneers.

This was a racing chronograph made by Elliot Brothers from London, in its massive transport box. It belonged to the Automobile Club de France in 1922, and was featured in La Science et la Vie.

Other important timepieces were the chronograph by Henri Chaponnière, used in the 1924 Klausen Pass race, and the time-pressure registration chronograph by Löbner, as used in the record drives with Fritz von Opel's rocket car RAK 3.

This was a diverse exhibition. Off the automobile theme, and not expecting weaponry, we were momentarily surprised to see a modified 9mm Zoraki pistol coupled to a Hanhart stopwatch, and a most intriguing early twentieth century electric chronometer from d’Arsonval, with an accompanying image showing it in use, to test the reaction times of Great War French pilots.

In all, a remarkable assembly of items one might spend a lifetime struggling to find in museum reserve collections, but gathered for the occasion and the great enjoyment of all present. (All photos by James Nye except where stated).

Christ transformed into an astronomer

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

As I have a special interest in historical scientific instruments, I was intrigued when I first saw this clock some twenty years ago in Somerset House in central London, overlooking the River Thames.

As far as I remember, the exhibition label did not comment on the figure of a man looking through a telescope, with a pair of dividers in his left hand and a globe at his feet. I was intrigued. The first telescope was developed in 1608. Could this be a very early representation of such an instrument in use?

Sir Arthur Gilbert and his wife Rosalinde formed one of the world's great decorative art collections, which he donated to Britain in 1996. Parts of it were on display in Somerset House from 2002 to 2008. After that, the collection was transferred on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, where a generous selection is on display in Gallery 70.

And here I saw the clock again, and learned something I had failed to understand when I first saw it.

The silver-gilt, ebony and ivory clock of architectural form, 76.5 cm high, is a combination of a shrine and a table clock, both made in the seventeenth century but assembled into the current configuration in the late nineteenth century, probably in Berlin. The clock is signed on the dial and the backplate by Elias Kreittmayer (1639–1697), a clockmaker working in Friedberg in Germany, while the shrine is ascribed to the Augsburg goldsmith Matthias Walbaum (1554–1632).

As the gallery label states ‘Made to appeal to specialist collectors, the shrine’s original Christian nature can still be seen in the figure with a telescope (above the dial), who was adapted from a representation of Christ. Such transformations are masterpieces in their own right.’

So the miniature telescope was not as old as I had thought.

There is a sobering story connected to the clock. One of its previous owners was Nathan Ruben Fränkel (1848–1909), a Jewish clockmaker from Frankfurt who built up an encyclopaedic collection of timepieces. It is not known what happened to this clock after his death and in the years before it resurfaced in 1975. And this uncertainty is alarming because of the extent of persecution experienced by his family.

Friedrich and Klara Fränkel, who ran a thriving watch business in Frankfurt, were forced into bankruptcy by the Nazis. In 1938, they fled to France where they narrowly escaped deportation and survived the war in hiding.

The clock has formed part of a special provenance display in the V&A 'Concealed Histories: Uncovering the Story of Nazi Looting' (December 2019–June 2021).

Let’s end on a more uplifting note.

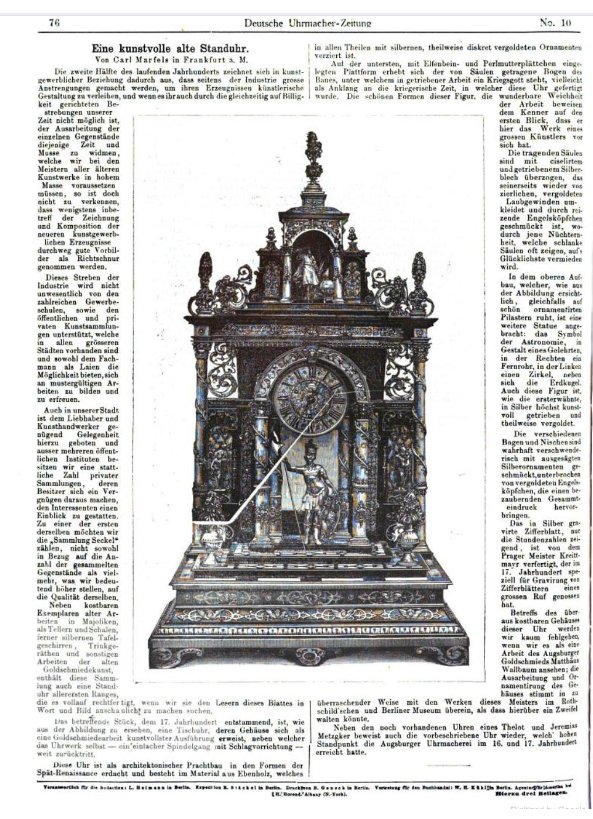

In 1890, the German clock collector Carl Marfels (1854–1929) presented the clock in the Deutsche Uhrmacher-Zeitung, the journal for clock- and watchmakers. His article is illustrated with a photo on which the telescope and the globe can clearly be seen. Marfels does not seem to have realised that the object had been doctored with. He concludes: ‘[…] the clock is yet another proof of the high standard of clockmaking in Augsburg in the 16th and 17th centuries’.

If it were indeed original, the clock would have contained a very early representation of a telescope — but we now know better.

A version of this blog post was published in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, No 160 (March 2024), p. 19.

A deadly wind up

This post was written by James Nye

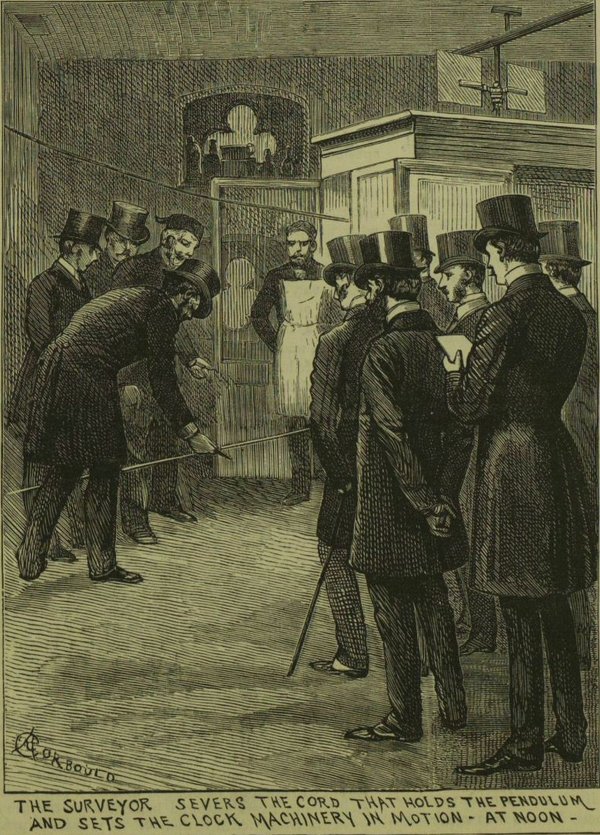

Horology is rarely gruesome, but on this occasion it certainly was. One of the largest and most impressive Gillett & Johnston clocks was installed in the Royal Courts of Justice in 1883. Its commissioning was accompanied by much pomp and ceremony, duly recorded on 29 December in the Illustrated London News.

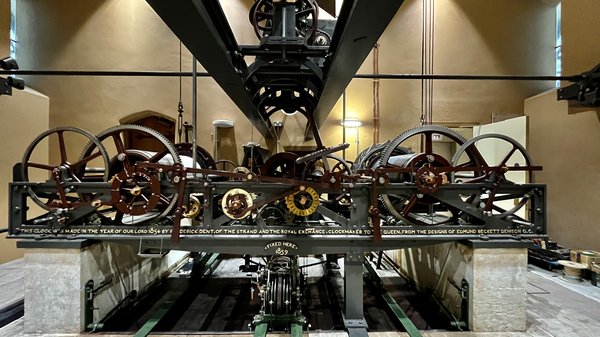

The mechanism utilises a double-three-legged gravity escapement together with a remontoire, capable of excellent timekeeping.

Gillett’s were certainly irritated in May 1893 by a correspondent in the Horological Journal suggesting their clock had wandered by 15–30 seconds per day in mid-1892. They published their own record, showing frankly astonishing accuracy.

The clock will have involved a significant amount of labour to wind by hand, and unsurprisingly an electric winding motor was added later. The date of the motor remains unknown but it could well be the one shown here.

It sits on a twin railway track, which runs laterally in front of the movement, and on which the motor is moved opposite each of the three winding arbors in turn, engaged, and then energised to perform the winding of the weights.

The winding round at the Royal Courts has always involved hundreds of smaller clocks, as many as 800 at one time, as well as the large clock. In 1937, the 25-year-old Tommy Manners took over the job, and settled into a long-established routine, touring the whole complex, with a once-weekly visit to the tower to wind the big clock.

This lasted through the 1930s, through the Second World War, into the sunlit uplands of the 1950s, until the morning of Guy Fawkes’ Day 1954. Around 9am on 5 November, Manners climbed to the tower as usual. He was under notice not to get too close to the flywheel when winding was underway, but somehow his dustcoat was caught, the fabric becoming quickly wound tight. He was trapped, unable to escape, and if he cried out, no-one heard above the roar of the traffic below, as the clock motor, anaconda-like, squeezed the life out of him.

Something else not heard was the strike of the clock, resulting in two engineers climbing to the clock room some 90 minutes later to find out why. Somehow, Manners had become freed from the motor, and was lying beside it. Rapid first-aid was to no effect, and he was transferred to Charing Cross hospital, but in vain.

An inquest at Westminster a week later recorded a verdict of accidental death, noting that Manners had been alerted to the risks posed by the flywheel. One outcome of the tragedy was the fitting of the serious safety cage around the whole mechanism, visible in the accompanying image. A modern micro-switch arrangement now prevents the motor being operated except at a distance.

The original news caught the attention of many a newspaper editor round the world. Both the Guardian (6 November) and The Times (13 November) covered the incident. The Sarasota Herald (6 November) ran the story with the dramatic headline, ‘Clock Winder is Killed by his Favorite Clock’.

A sobering tale.

The last piece of the jigsaw: a relatable story for researchers

This post was written by Su Fulwood

Research is, of course, interwoven through my work. One long-term project is about women and their roles in horology. This started when I was working with watchmaker Geoff Allnutt in his shop and workshops at 8 West Street, Midhurst. Geoff challenged me to go through lists of watch and clockmakers to note down all the women mentioned. After finding hundreds of women among the men, one name stood out: 'Mary Ann Lawrence, West Street, Midhurst'.

A quest began in earnest to find out where in the street Mary Ann had worked.

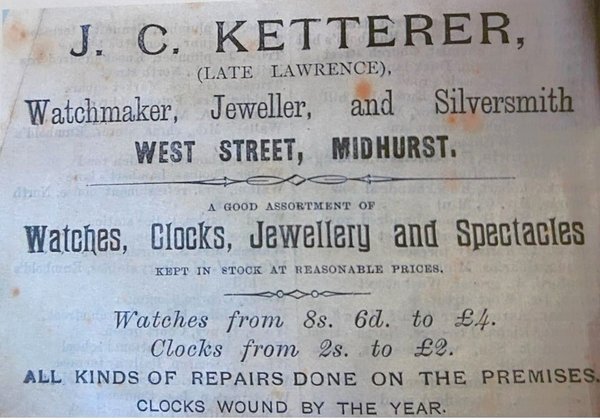

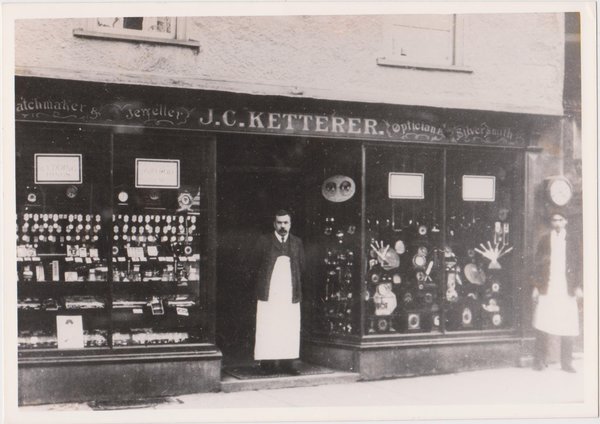

Years have passed and our research has covered many individual women, including, gradually, lots about Mary Ann. We discovered that she was actually from a well-known family of local watchmakers, the Wrapsons. We found that she took over her brother's premises in West Street following his death. We also discovered that she was close friends with fellow watchmaker, Joseph Charles Ketterer.

Ketterer, we knew with certainty, had run his business until 1914 from the premises Geoff now occupies.

We couldn’t say, however, whether Ketterer took over from Mary Ann or whether she had worked from another shop. It wasn’t uncommon in Midhurst for there to be two watchmakers in the same street at a similar time.

We did know Mary Ann retired around 1895, and that Ketterer was the executor of her will when she died. We just didn't have that last all-important piece that would tell us if she was part of the history of 8 West Street. It was frustrating.

Until now that is ... seven years later, when a chance conversation revealed the existence of a different advert for Joseph Charles Ketterer’s business.

When we saw it we couldn’t believe our eyes. There at the top, unexpectedly, was exactly the information we had been looking for. The words 'J. C. Ketterer (Late Lawrence)' were pure gold for us. It meant that Mary Ann Lawrence (who describes herself as 'Mistress Watchmaker' in the 1881 Census) was running her watchmaking business from the shop before Ketterer. This also meant that the same premises had belonged to her brother Charles Wrapson and, before him, their mother, Mary Wrapson.

Our research began by looking at watchmaking women across the country. But it has become very personal, as finally we were able to show that two of those women inhabited the exact spaces we work from today.

In the meantime, along with my research about women and horology, I get to work with other women today, as more are attracted back to watch and clockmaking.

The tools are important too

This post was written by Seth Kennedy

Many horological workshops contain old tools. It seems to go with the territory. There is something about using a hand tool that has already been around for a century or more. It brings questions, wondering whose hands have previously worked with this object over several generations and what timepieces were they working on?

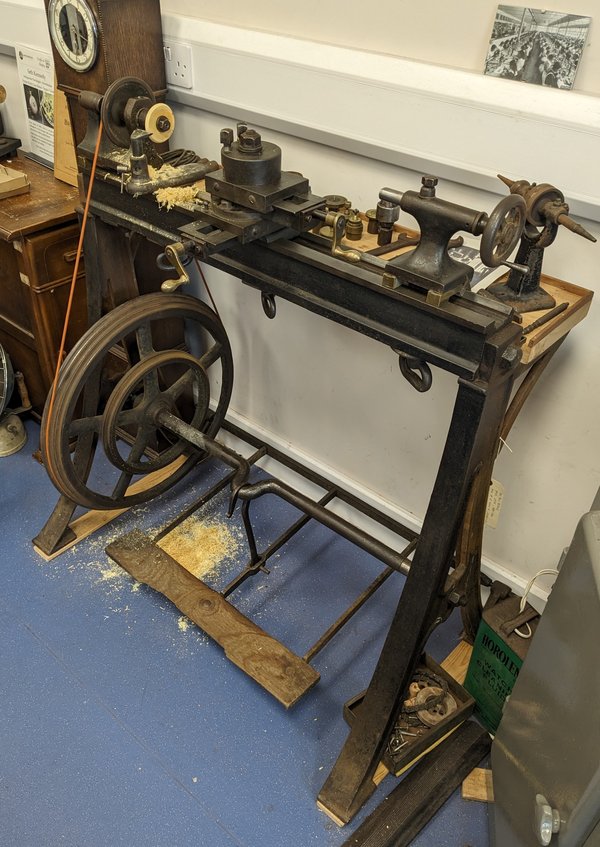

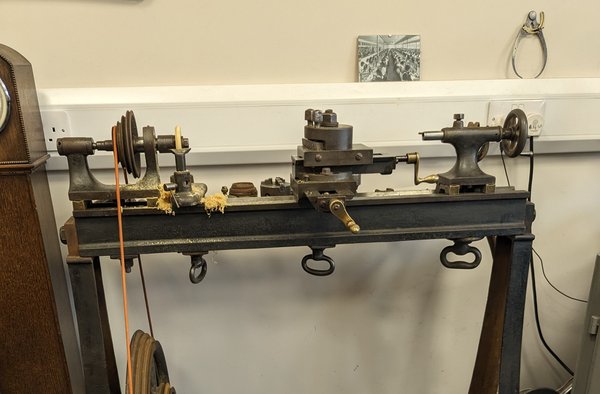

With thanks to a fellow restorer, I recently became custodian of something a bit larger than a saw or a file. It’s a plain lathe by Pfiel most likely made in the late 19th century. Pfiel & Co were tool makers and retailers with a large shop and warehouse on St John Street in Clerkenwell. There are a few details about these lathes that make them distinguishable and so it is possible they were actually cast and machined in London to Pfiel specifications.

The centre height of the spindle is 3.5”, or at least it was, since on this example some home-made brass spacers have been added under the head and tailstock so that larger parts could be turned. These spacers fit the flat front and veed back surfaces of the lathe bed.

The treadle board itself is an incredible survivor, showing its wear of a century of use. Also remaining, though unusable, is a very old gut line that was previously used to connect flywheel to spindle.

What makes this lathe particularly special is that its history is known. It came from the workshop of Daniel Parkes, a fourth generation clockmaker/restorer who was active in Clerkenwell until retirement in 1989. He was a founder member of the AHS and some of his tools are on display in the museum of The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. Parkes used only traditional equipment and methods in the restoration of fine English clocks of the 17th and 18th century golden age.

The lathe could have come from his family’s workshop on Spencer Street, which was destroyed by a V1 bomb in June 1944 but from which he salvaged some equipment. Or it might have already been in the workshops that Parkes then moved to on Brisset Street, where a partnership was formed with A. & H. Rowley, also a firm with long Clerkenwell roots.

Either way, someone in one of those businesses needed a lathe in around 1890 and so walked down the road to the Pfiel shop and bought this one. After Parkes’s retirement it went to Mike McCoy, then to Matthew Hopkinson and then recently to my workshop.

It has now had some cleaning, oiling, a hidden strengthening plate added to the treadle, a new leather belt fitted and a new shelf added as the original had gone missing.

Tools are meant to be used and so, after perhaps 30 years of slumber it will now occasionally be put into action again, for turning boxwood chucks used in watch case making and other light tasks.

Backwards and forwards

This post was written by James Nye

I am shocked to realise it is now a decade since I blogged about Enicar watches. As collectors know, Enicar derives from reversing the family name of the owners, Ariste and Emma Racine. Signing clocks and watches like this has a long tradition, with an interesting variety of explanations.

Back in the December 1993 issue of Antiquarian Horology, Sebastian Whitestone discussed some watches that bogusly claimed a London origin, but which in reality were from the Friedberg region and signed Lekceh, Legeips, Rengaw, Renpuarg and Ysorb. Reverse these and we have the less exotic Heckel, Spiegel, Wagner, Graupner and Brosy.

Mirrors reverse images, and tellingly, Spiegel also used the giveaway signature Miroir, London. The word ‘spiegel’ is German for mirror, and thus another pun.

But not all Friedberg makers reversed their names when they added a London location. Eckert and Schreiner signed (falsely) from London, but used their normal names.

Surveying the Ashmolean Museum's watches in the December 2000 issue of AH, David Thompson enlarged the geography, tying a watch signed ‘Renpuarg, London No. 4’ to Augsburg.

Alice Arnold Becker revisited backward signatures in AH in June 2014, taking the line that it was all marketing. The watchmakers perhaps falsified locations to secure the gravitas and caché of the London market – creative branding, familiar today.

Dutch horologist John Selders has also studied this phenomenon, publishing several pieces in Tijdschrift and summarising in 2015 with a list of 24 such reversed names, from the late seventeenth century to the turn of the nineteenth, and noting that some makers signed from Paris, not just London.

Strangely, precisely the same thing happened in Britain. English and Scottish makers of watches also reversed their names. An example is a watch by James Peddie of Stirling, signed on the back plate Jas Eiddep (see Clocks, April 2019). More prolific is Eardley Norton, whose signature Yeldrae Notron appears with surprising frequency. Usher & Cole’s apprentice John Wontner later signed objects as Rentnow. Cole signed as Eloc.

What on earth were all these people doing? There are several theories. Some assume distant makers wanted to capture borrowed prestige, and value, by signing from London, or Paris – an element of passing-off. A false signature disguises true authorship.Some suggest it was done to avoid taxes. Perhaps it limited redress to a real maker. Or perhaps it shows the maker’s sense of humour?

Does it all echo the original Rolex/Tudor division – an affordable product from the same stable, but differentiated?

No firm conclusions are possible, but some theories are surely too far-fetched. Tax officials won’t be fooled by mirror-writing. Signing a watch carries a maker’s chosen identity out into the world, and should be permanent, and memorable. A sense of whimsy could be involved, maybe even a sense of a brand that stands on its own, distinct from the name of the controlling mind involved.

In all, a subject that deserves more than a backwards glance... and if anyone has any other examples of reversed clock and watch signatures, please do tell me!

The watches of Samuel Pepys

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

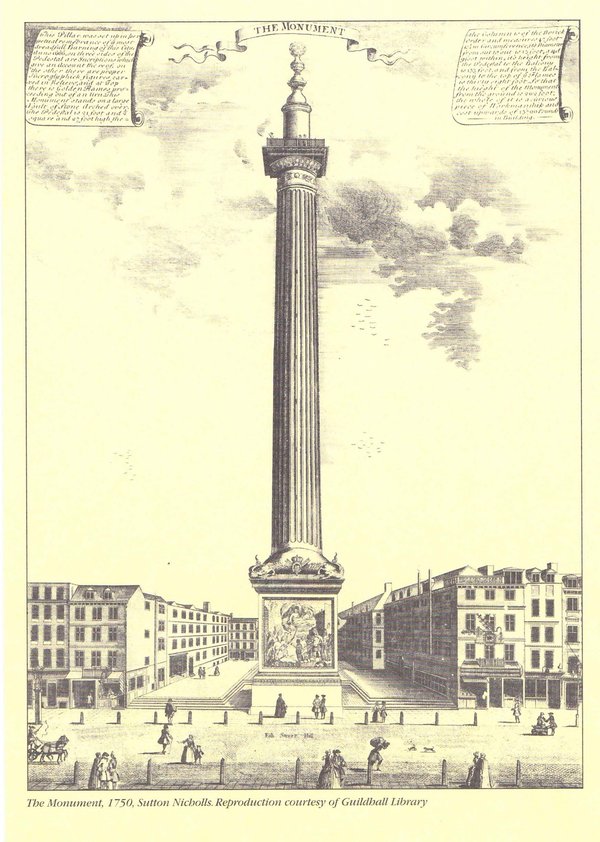

The office of the AHS in Lovat Lane in the City of London is a stone’s throw away from The Monument, erected to commemorate the Great Fire of London of 1666.

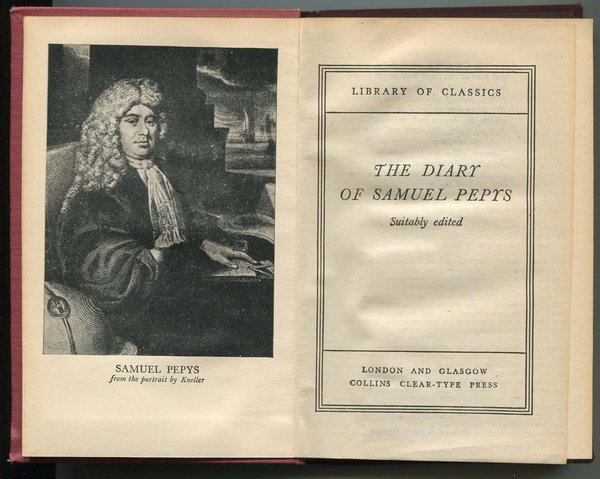

The fire was famously reported in The Diary of Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), which ‘is unique, no less for Pepys’s self-revelation, than for its graphic picture of social life at the time of the Restoration’. This is a quote from the preface in my copy of the Library of Classics edition first published in 1825. Running to 640 pages, it yet contains scarcely half of the manuscript. It had also been ‘suitably edited’, which perhaps means that for example anything to do with his bodily functions or his amorous exploits had been removed.

A more complete edition appeared in 1893, and this forms the basis for a magnificent website which offers ‘the full text of his diary, along with several letters sent or received by Pepys, plus thousands of pages of further information about the people, places and things in his world’.

It is searchable, and if you want to find out what Pepys wrote about clocks and watches, you will find some two dozens entries.* Let’s follow one trail, all to do with watches:

Monday 17 April 1665: 'This day was left at my house a very neat silver watch, by one Briggs, a scrivener and sollicitor […].'

Friday 12 May 1665: 'To the ’Change [the Royal Exchange] and thence to my watchmaker, where he has put it [i.e. the watch] in order, and a good and brave piece it is, and he tells me worth 14l. which is a greater present than I valued it.'

Saturday 13 May 1665: 'To the ’Change after office, and received my watch from the watchmaker, and a very fine [one] it is, given me by Briggs, the Scrivener. […] But, Lord! to see how much of my old folly and childishnesse hangs upon me still that I cannot forbear carrying my watch in my hand in the coach all this afternoon, and seeing what o’clock it is one hundred times; and am apt to think with myself, how could I be so long without one; though I remember since, I had one, and found it a trouble, and resolved to carry one no more about me while I lived.'

Wednesday 13 September 1665: 'Up, and walked to Greenwich, taking pleasure to walk with my minute watch in my hand, by which I am come now to see the distances of my way from Woolwich to Greenwich, and do find myself to come within two minutes constantly to the same place at the end of each quarter of an houre.'

Friday 22 December 1665: 'I to my Lord Bruncker’s, and there spent the evening by my desire in seeing his Lordship open to pieces and make up again his watch, thereby being taught what I never knew before; and it is a thing very well worth my having seen, and am mightily pleased and satisfied with it.'

Saturday 22 September 1666: 'My Lord Brunck […] now give me a watch, a plain one, in the roome of [instead of] my former watch with many motions which I did give him. If it goes well, I care not for the difference in worth, though believe there is above 5l.'

All this is very interesting, but it leaves questions unanswered.

Why was Pepys given a watch 'by one Briggs, a scrivener and sollicitor', about whom we hear no more in the diary, and who is not mentioned in Claire Tomalin’s excellent biography published in 2002? Did he want to curry favour with Pepys, perhaps hoping to benefit somehow?

We are not told the name of the man who had serviced his watch, nor do we have details of the watch except that it was worth £14 and came 'with many motions', which we take to mean that it not just showed the time but also had additional functions that could make a watch such an attractive possession.

But why, we may ask, had Pepys earlier in his life been so frustrated with a watch? Had it malfunctioned?

His wife had her own watch (Saturday 9 February 1666/67: 'This noon come my wife’s watchmaker, and received 12l. of me for her watch') but it led to irritation (Wednesday 3 April 1667: ‘and to bed, vexed … that my wife’s watch proves so bad as it do').

Or had it been the anxiety that a watch could draw unwanted attention, like we hear these days of brutal daylight robberies of expensive watches? On Wednesday 1 January 1667/68, Pepys ‘took coach and home about 9 or 10 at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing, I did go back.’

If he was so taken with his fancy watch that he could not stop consulting it when he set out with it in his coach, why did Pepys later give it away to William Brouncker (c. 1620–1684), and accepted a simpler and less valuable one in return?

Lord Brouncker was from 1662 to 1677 the first president of the Royal Society, an office to which Pepys himself was to be appointed in 1684, long after he had stopped writing his diary.

Brouncker features prominently in Pepys’s diary; they were neighbours and on friendly terms. So perhaps Pepys gave him his fine watch simply from the goodness of his heart, and that is a nice note to end on.

* Searching on ‘clock’, one must weed out hundreds of 'o’clocks', and ‘watch’ is of course often found to mean ‘look at’, but with some patience I found 23 pertinent entries which I shall be happy to share with anyone interested.

Ringing in the New Year

This post was written by Andrew Strangeway

As a clockmaker, or practising horologist, there is one particular moment while waiting for a clock to strike when time seems to slow down.This moment is more daunting when the streets outside are lined with 100,000 people and millions more are watching live on television, and streaming, waiting to hear the clock chime.

On December 31st it all comes down to a single moment, when the nation watches and waits for Big Ben to ring out and signal the start of the new year. Behind the scenes, however, months of preparation go into ensuring that this first hammer-blow falls precisely on time. Besides the installation of additional broadcast equipment, regular servicing, and thrice weekly winding there is also timekeeping: ensuring, literally, that the clock stays on time.

In the months leading up to the end of 2023, the timekeeping of the Great Clock was a core focus. After the break of six years during the servicing of the clock and tower, the twice-daily live chimes finally returned to BBC radio airwaves on November 6th. This New Year marked the 100th anniversary since the bells were first broadcast live for New Year’s Eve. It was a matter of pride that the clock should perform well and strike on time.

When it was first installed, the Great Clock was, by some margin, one of the most accurate public clocks in the world. The original specification for the clock set down in 1846 by George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, required that ‘the striking machinery be so arranged that the first blow for each hour shall be accurate to a second of time’. As clockmakers our job is to ensure that the clock remains true to this original purpose. To our advantage, we have highly accurate timekeepers to compare the Great Clock against and, armed with this information, we can regulate the pendulum carefully and actually comfortably exceed the original target for accuracy.

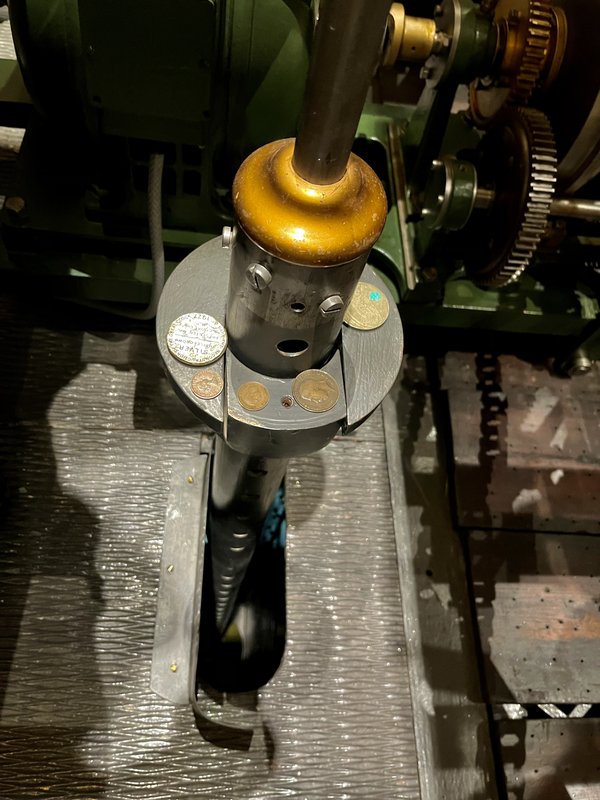

Since starting at the Palace of Westminster in August 2023, I have implemented the use of a new custom-made timer to increase the accuracy of the timing of the first hammer-blow of the hour and an improved regimen of regulating the rate of the clock’s pendulum. The core mechanics of regulation remains as ever: the placing or removing of weights, in the form of old currency, on a small platform partway down the length of the pendulum rod. Famously, one pre-decimal penny added speeds up the clock by about 2/5th of a second over 24 hours. These are a little too weighty and the adjustment too coarse if one is aiming for a finer degree of accuracy. I have begun using ha’pennies and farthings for regulation, kindly lent for the purpose by my colleague in the clock team, Ian Westworth. These speed the clock up by about a quarter of a second a day and a tenth of a second a day respectively.

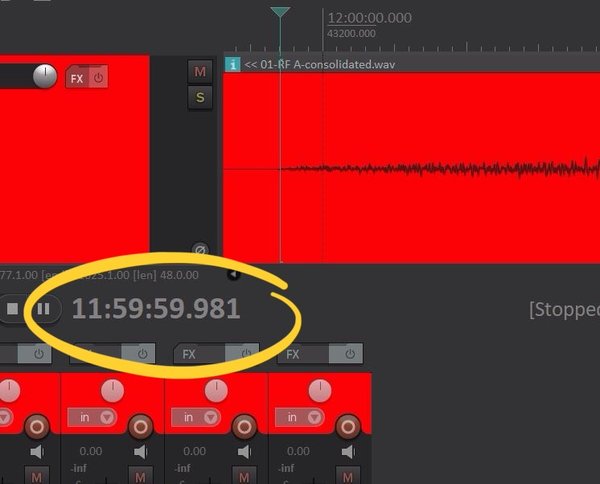

In the final days running up to New Year’s Eve I was at the top of the tower, on the hour, throughout the day to take a timing reading from the strike and to make small adjustments to bring the clock precisely to time. As luck would have it, on the evening of the 30th we experienced heavy winds, which buffeted the tower and were enough to throw the clock out by 0.2 seconds by the morning of New Year’s Eve. I was able to correct for this by the evening. Midnight came and Big Ben struck, and the view of the fireworks from the top of the Elizabeth Tower was astounding. It was awesome to see the fireworks perfectly synchronised with the strike of the bell.

My timekeeping efforts were rewarded when we measured the timing of the strike from the sound recording compared with a GPS clock – these results were generously provided by Mark Powell of DeltaLive. The result was that Big Ben struck midnight at exactly 23:59:59.981, within less than a fiftieth of a second of midnight. That’s less than a fifth of the time it takes to blink your eyes. I must confess to being rather pleased with that!

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

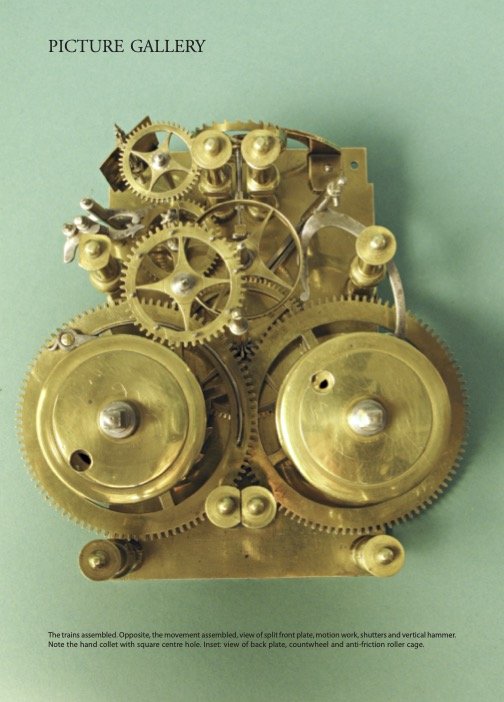

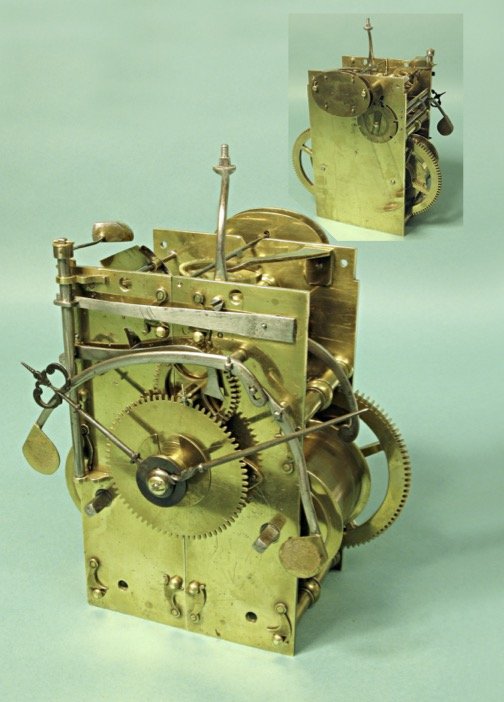

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Light among the lanterns

This post was written by James Nye

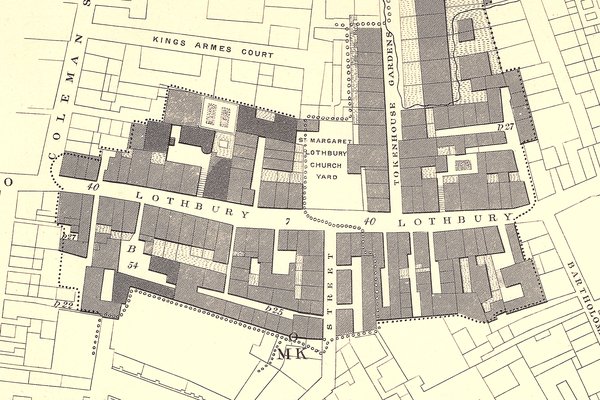

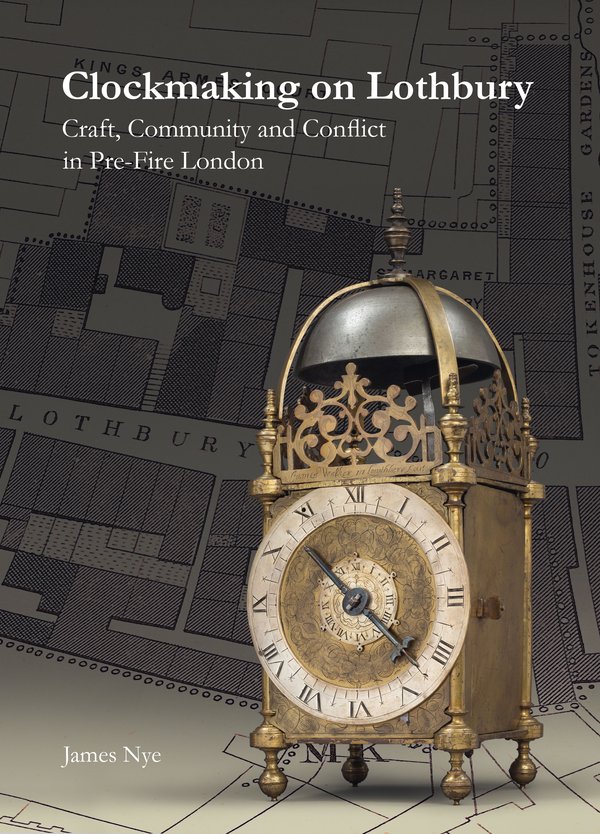

I used to walk regularly from Cannon Street tube station to the Clockmakers' Company office in Throgmorton Avenue, and on the way would walk down the west flank of the Bank of England, turn right and cross over to slip down Tokenhouse Yard. One day, passing St Margaret’s Lothbury, I stopped, and looked around. It struck me forcibly that Lothbury was really short, yet I knew that a fair number of lantern clocks were signed from addresses on the street. I was intrigued. Was this like restaurants crowding together and all benefiting from increased business?

This was back in 2018, and I conceived the idea of a deep dive into the street’s pre-Fire history. It was known for its founders, and for their ‘turning and scrating […] making a loathsome noise’. Was it such a bad place? Who else lived there, and what did they do? I recruited a research assistant, Caitlin Doherty, and together we planned trips to archives and libraries, following up hunches and leads developed together.

This all resulted in a lecture we jointly gave in November 2019, but I had to jettison more than half my material to squeeze it into a decent length. Then Covid struck and the larger work languished, until mid-2022 when I dusted it down and gave it a read. I was pleasantly reminded of much, but also conscious that a lot more could be done, so I strapped on the tanks and went overboard again.

I was still frustrated that on the first attempt I had failed to pinpoint the location of the Mermaid, the best-known Lothbury address, home to Selwood, Loomes and others, and from which the first pendulum clocks were sold in London. A punch-the-air moment occurred earlier this year when I finally found archival documents that revealed its whereabouts.

The project eventually grew to a book-length treatment and I am deeply grateful to the Society for backing its publication. It has recently been rolling through the presses. You can see pages being prepared for sewing here and the cover being embossed here.

Make no mistake, this is not a technical book about lantern clocks. But it is a forensic account of the small community in which one group of remarkable makers lived. It reveals who their neighbours were and the challenges they all faced, whether against the backdrop of the Civil Wars or the poisonous smoky atmosphere. It discusses the trades in which the merchants on the street were engaged, but reveals some of the poverty close at hand. I hope that in many ways it should throw some more light around the early life of many lantern clocks. And you can order it here!

Time's up!

This was post was written by Jonathan Betts

Have you ever had to endure a relentlessly boring after-dinner speech?

In these less-formal days there are fewer opportunities, but in the ‘good old days’ in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, when many of the elite of British society belonged to exclusive dining clubs, speeches could go on seemingly forever!

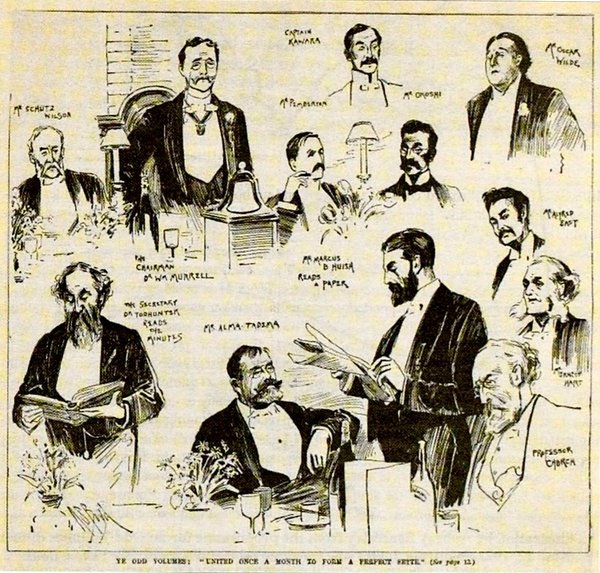

The Sette of Odd Volumes

The 'Sette of Odd Volumes', one of the more eccentric of such dining clubs, was founded in 1878 by the celebrated antiquarian bookseller, Bernard Quaritch (1819-1899). Over the following decades it was distinguished by having as members and guests many great achievers in the literary, scientific and academic worlds.

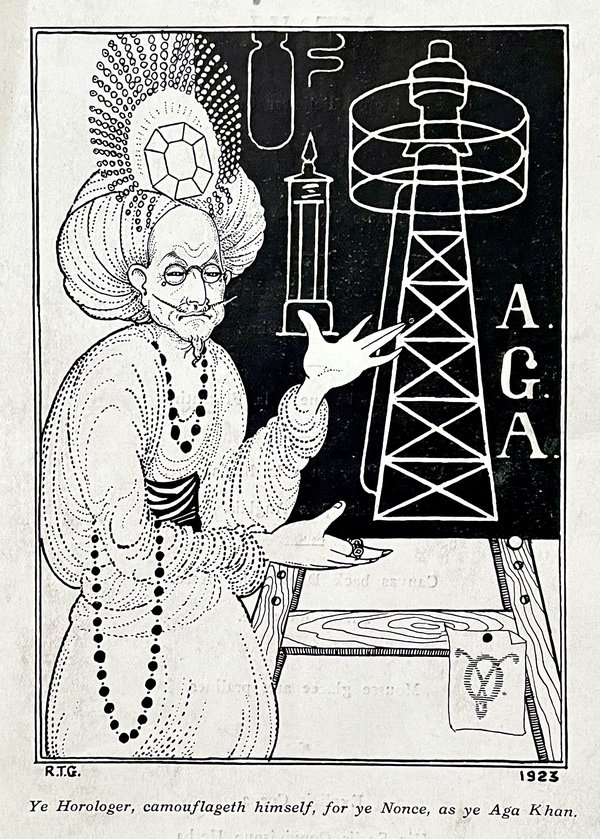

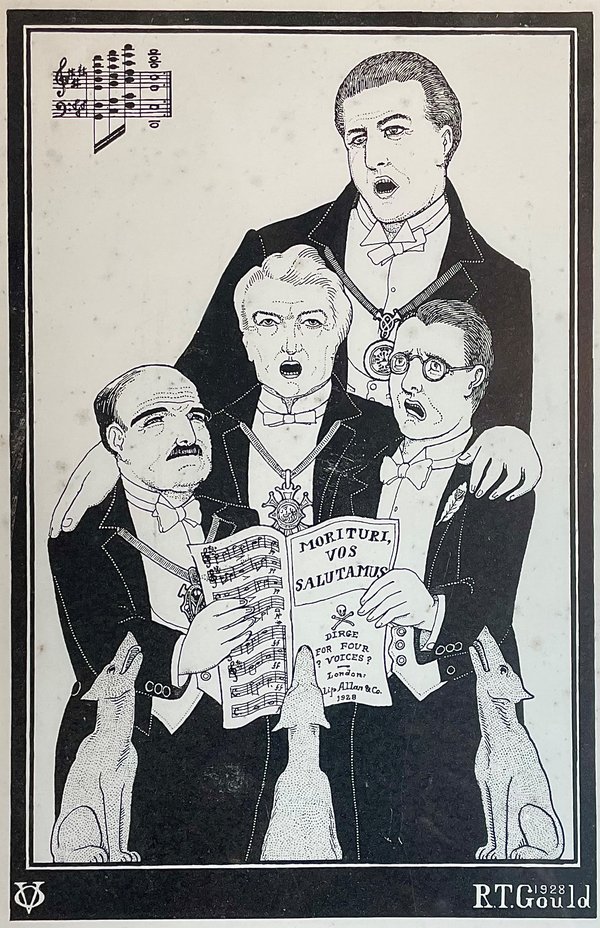

Horologically, our very own Rupert T. Gould (1890–1948) joined in 1920, and George C. Williamson (1858–1942), the antiquarian who published horology’s largest book, the catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan collection of watches, was also a member.

Members of the club were ‘brothers’ and adopted titles appropriate to their professions. Gould was ‘Hydrographer’ and Williamson was ‘Horologer’. The enforced, tongue-in-cheek jollity of the dinners required the exclusive use of their titles.

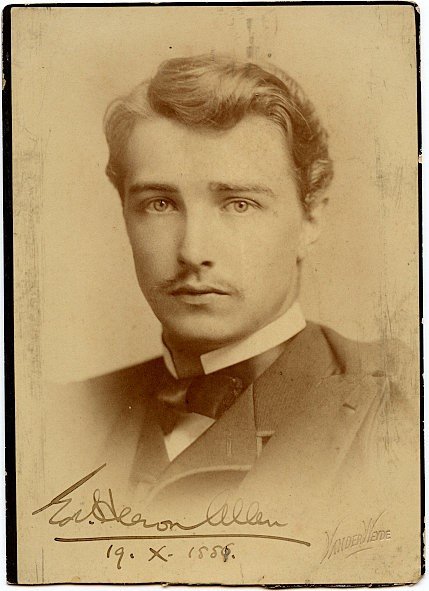

Oscar Wilde occasionally attended these Sette dinners as a guest. In later years, Wilde’s second son, Vyvyan Holland, was a Sette member, 'Idler', and was also a good friend of Gould's. Another great friend was the biologist and microscopist Edward Heron-Allen (1861–1943), ‘Necromancer’, who had joined the Sette back in 1883.

Each year, the Sette elected a new President, who sat in a grand throne-like chair when in office, and a Vice President, who would be President the following year. In 1891 Heron-Allen was about to be elected Vice President, and as a gift to the Sette (and as something of an aggrandisement to his new office!) he commissioned and presented a Vice President’s chair to accompany the President’s.

Those speeches

The Sette's activities were regulated according to a set of Rules, some of which were positively Pythonesque. For example, rule XVI was that 'There shall be no Rule XVI', and Rule XVIII insisted that 'No Odd Volume shall talk unasked on any subject he understands'.

One of the more sensible rules, however (No. XX), stated that 'No O.V.’s speech shall last longer than three minutes; if however, the inspired O.V. has any more to say, he may proceed until his voice is drowned in the general applause'.

Finding that this rule was constantly being disobeyed, and that evidently the ‘general applause’ was insufficient, in December 1891 Heron-Allen also commissioned and presented to the Sette an elaborate speaker’s bell, to ensure they stuck to time.

The bell

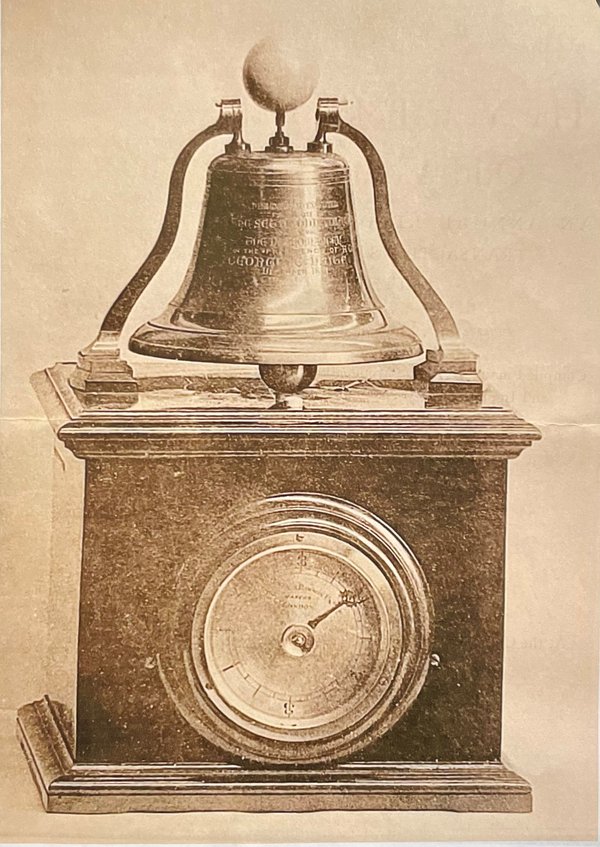

Made by the well-known Victorian electrical engineers, Woodhouse & Rawson, the bell is of exquisite quality throughout. Constructed in a mahogany case containing the electro-mechanical timer, the large bell, mounted on the top, has a slender rod running vertically through it, which had (now missing) a ball on top.

In operation, reminiscent of the way a time ball runs, the timer is set going and the ball (which was probably an ivory billiard ball originally) is seen to slowly climb up from the bell. The ascent is controlled by a clockwork worm-and-fly governor, and at the point at which the three minutes has elapsed, the ball, now about 2.5 inches above the bell, suddenly drops back down to the bell, which then begins to ring very loudly, an electrical make-and-break hammer operating on the inside.

For the speaker, having a miniature time ball inexorably rising in front of him while he was talking must have been quite off-putting and, needless to say, the timing device was not popular. One can only imagine what Oscar Wilde would have thought (and said!) if the thing was set going as he began giving an after-dinner speech!

In fact, a certain flexibility was built into the controls of the bell, and the operator (presumably the Master of Ceremonies) was able to pause the clock, or even ring the bell in advance, if deemed necessary!

But its presence as a gift would soon be quietly but firmly removed anyway, and this fascinating and beautiful object, and the Vice President’s chair, were not seen again. This was owing to an incident which left Edward Heron-Allen unpopular among the elders of the Sette and which caused him to resign from the Sette a year or so later.

The incident, which is described in an excellent book by John Mahoney (The Richard Le Gallienne versus Edward Heron-Allen ‘Incident’ at The Sette of Odd Volumes, privately published, Tallahassee, 2023), concerned the proposal for membership of the Sette of the author and poet Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947).

Le Gallienne had had a brief affair with Oscar Wilde, and it seems that at the time he was being proposed for the Sette, Heron-Allen had made a remark in confidence at a private dinner party about Le Gallienne’s sexuality. Unfortunately, this remark was not treated in confidence, and Le Gallienne got to hear of it. This would, given the illegality of homosexuality at the time, be a very serious matter for him.

The scandal which ensued polarised views within the Sette, causing Le Gallienne’s election to be dropped temporarily and Heron-Allen to later resign. The chair and timer were thus quietly put away, though the chair does in fact remain in the Sette’s possession; the timer escaped at some stage and only resurfaced a few years ago.

For Heron-Allen the story ended happily, however. He would re-join the Sette thirty years later, and he enjoyed many a dinner with Gould, Holland and his other friends, no doubt having to put up with the long speeches after all.

A varied horological life

This post was written by Su Fulwood

'I have to ask you, is this your actual job?' This was put to me last week while I was winding one of the clocks in the collection at Goodwood House, the home of The Duke and Duchess of Richmond in West Sussex. Well, yes it is – one of them anyway, I do a few things.

I’m a freelance collections advisor, researcher and curator, so I work with all things from costume to archaeology, but more than half of my projects are horology related. Possibly this is because clocks, as something with a beating heart metaphorically, evoke memories and stories as well as encompassing art, science, technology and history, so as an example of material culture they are multifaceted and valued.

More than anything else, clocks are firmly connected to people, their knowledge and emotions. Working with them enables me to meet and work with excellent people, to travel, and it defines the places I visit.

I’ve recently returned from a job in York that enabled me to explore the coast from Staithes to Scarborough (I suspect turret clock specialists can relate to this).

This year began with a project working with the fabulous Cumbria Clock Company and their newer recruits. I can't express how privileged I feel to work with both experienced clockmakers and the next generation of horologists.

Back at Goodwood, I have an annual presence at The Festival of Speed and The Revival exposing me to all manner of wonderful cars, their clocks and watches.

My research on women working in horology with Geoff Allnutt also leads to fantastic places. The horology community is unlike any other and this introduction is also a thank you to all at the Antiquarian Horological Society who have supported me with my work. More to come!